Wines That Could Be Appreciable for the Local Consumers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NINGXIA AUTONOMOUS REGION POST EVENT REPORT Introduction

ASIAN WINE – THE SILK ROUTE 2nd Forum and Tasting YINCHUAN – NINGXIA AUTONOMOUS REGION POST EVENT REPORT Introduction 2nd Asian wine Forum-Tasting Baudouin Havaux Replicating Vinopres S.A Chairman - CMB the cultural One of China’s most exciting new wine regions lies in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region in nor- thwest China. Two thousand years ago, Yinchuan lay on the Silk Road, along which goods and ideas interactions travelled between China and Europe: silk went west, and wool, gold, and silver came east. In more recent history, Ningxia was a poverty-stricken coal region whose dusty scrubland was in danger promoted by the of desertification. But, in the nineteen-nineties, the government began to invest seriously in its in- world’s historic frastructure, irrigating immense tracts of desert between the Yellow River and the Helan Mountains. Recently, local officials received a directive to build a “wine route” through the region, similar to Bordeaux’s Route des Vins. trade routes European winegrowers, hired by the government as consultants, had identified Ningxia’s continental climate with dry summers, and plentiful sunlight as ideal for vineyards. However, the region also experiences harsh, freezing winters, making it necessary for winemakers to bury their vines until The BRWSC strikes gold with its second event, hosted by Ningxia spring to protect them from the cold. After a first successful edition in the burgeoning Fangshan region of Beijing in 2016, Vinopres and the Beijing International Wine & Spirit Exchange teamed up this year with representatives from With a strong sense of flair and self-confidence, in less than 20 years, Ningxia has become the heart one of China’s most prominent, and talked-about wine regions – Ningxia – to host the 2018 Belt & of Chinese wine production, with over 100 registered wineries in production. -

Food Safety in China: Implicationsof Accession to the WTO

China Perspectives 2012/1 | 2012 China’s WTO Decade Food Safety in China: Implicationsof Accession to the WTO Denise Prévost Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5807 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5807 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 30 March 2012 Number of pages: 39-47 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Denise Prévost, « Food Safety in China: Implicationsof Accession to the WTO », China Perspectives [Online], 2012/1 | 2012, Online since 30 March 2015, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5807 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5807 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Food Safety in China: Implications of Accession to the WTO DENISE PRÉVOST* ABSTRACT: The interaction between trade and health objectives has assumed critical importance for China since its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). The wish to improve its access to foreign markets has had a visible impact on China’s food safety policy, providing significant impetus for far-reaching reforms. The WTO Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement), to which China is now bound as a WTO Member, sets out a “best practices” regulatory model with which national food safety regulation must comply. The disciplines it entails on regulatory autonomy in the area of food safety may present considerable challenges for China but have the potential to promote rationality in such regulation and to prevent food safety regulations that are based on unfounded fears or are a response to protectionist pressures from the domestic food industry. -

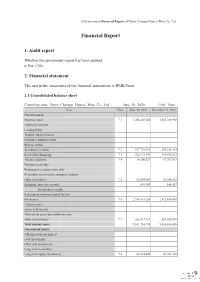

Section 9 Financial Report

2020 SemiannualFinancial Reportt of Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co., Ltd. Financial Report 1. Audit report Whether the semiannual report has been audited □ Yes √ No 2. Financial statement The unit in the statements of the financial annotations is RMB Yuan. 2.1 Consolidated balance sheet Compiling unit: Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co., Ltd. June 30, 2020 Unit: Yuan Item Note June 30, 2020 December 31, 2019 Current assets: Monetary fund 7.1 1,476,207,055 1,565,783,980 Settlement reserves Lending funds Tradable financial assets Derivative financial assets Bills receivable Accounts receivable 7.2 167,738,633 266,218,153 Receivables financing 7.3 222,918,741 316,470,229 Advance payment 7.4 10,200,527 67,707,537 Premium receivable Reinsurance accounts receivable Receivable reserves for reinsurance contract Other receivables 7.5 25,594,801 24,246,812 Including: Interest receivable 698,347 148,927 Dividends receivable Redemptory monetary capital for sale Inventories 7.6 2,936,133,260 2,872,410,407 Contract assets Assets held for sale Non-current assets due within one year Other current assets 7.7 262,917,721 267,424,938 Total current assets 5,101,710,738 5,380,262,056 Non-current assets: Offering loans and imprest Debt investments Other debt investments Long-term receivables Long-term equity investments 7.8 42,810,445 43,981,130 2020 SemiannualFinancial Reportt of Yantai Changyu Pioneer Wine Co., Ltd. Item Note June 30, 2020 December 31, 2019 Other investments in equity instruments Other non-current financial assets Investment real estate 7.9 -

China Agri-Food News Digest 2014 Index

China Agri-food News Digest 2014 Index (Total No 13-24) Policies January No.1 Central Document targets rural reform China Focus: Rural land reform boosts equity, efficiency Key policy document places greater emphasis on cleaner land and safer food China eyes more professional farmers amid rural reform College graduates set on farming Better rules on GM food labels needed: expert No modification of China's GM food regime Raising corn output is food for thought China to increase subsidies to grain production Satisfying the growing appetites Local watchdogs empowered in food safety shake-up Toward food secure China February Bigger farms reap bigger fortunes upon rural land reform Market to play bigger role in agri-product pricing: NDRC China to allow private investors to establish rural commercial banks Chinese lenders urged to plow new fields China to improve population's nutrition Mainland Chinese urged to drink more milk as part of national nutrition plan China scythes grain self-sufficiency policy China will not import large quantities of food China announces pork purchase scheme China is model of agriculture development: IFAD president Provinces work on plans to enhance farmers' land rights Labor shortage looms in eastern China China to focus on family farms in drive to commercialise Chinese farmers look to more land reform 1 SPP vows crackdown on food, environmental crimes March China rises to new rural challenges Farmland protection concerns Chinese lawmakers China to spend 10 pct more on farm subsidies in 2014 -minister China pledges -

PE & QSR: Ambition on a Bun Asian Venture Capital Journal | 06

PE & QSR: Ambition on a bun Asian Venture Capital Journal | 06 November 2019 Many private equity investors think they can make a fast buck from fast dining, but rolling out a Western-style brand in Asia requires discipline on valuation and competence in execution Gondola Group was among the last remaining assets in Cinven’s fourth fund, and as one LP tells it, exit prospects were uncertain. The portfolio company’s primary business was PizzaExpress, which had 437 outlets in the UK and a further 68 internationally as of June 2014. Expansion in China by the brand’s Hong Kong-based franchise partner had been measured, with about a dozen restaurants apiece in Hong Kong and the mainland. Cinven wasn’t willing to be so patient. In May 2014, Gondola opened a directly owned outlet in Beijing – as a showcase of what the brand might achieve in China when backed by enough capital and ambition. Two months after that, PizzaExpress was sold to China’s Hony Capital for around $1.5 billion. By the start of the following year, Cinven had offloaded the remaining Gondola assets and generated a 2.4x return for its investors. The LP was “pleasantly surprised” by the outcome. Hony’s experience with the restaurant chain hasn’t be as fulfilling. Adverse commercial conditions in the UK – still home to 480 of its approximately 620 outlets – has eaten into margins and left PizzaExpress potentially unable to sustain an already highly leveraged capital structure. Hony is considering restructuring options for a GBP1.1 billion ($1.4 billion) debt pile. -

China Food Safety Law - Practical Procedures, Trends and Opportunities for Dutch Companies

China Food Safety Law - Practical procedures, trends and opportunities for Dutch companies Yibo Jiang, Henk Stigter, Martin Olde Monnikhof Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Beijing, February 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 China Food Safety Law 2015 4 Practical Procedures 7 Dairy Products 18 Meat Products 20 Hong Kong 22 Trends 24 Swot Analysis 26 Annexes 30 A list of abbreviations of authorities used in the brochure List of the 27 recognized health functions for dietary supplements Bibliography 32 2 INTRODUCTION In the previous century, one of the strategic goals towards a “moderately prosperous society” of the Communistic Party was “providing people with adequate food and clothing”. In a country where, as the Chinese saying goes, “food is seen by people as important as heaven”, food has always been the utmost import thing for rulers to keep its people content. A few decades ago, when a large part of the population still struggled to survive in poverty, the focus on food in China used to be simply providing sufficient food supply. Today, this focus has shifted towards ensuring food safety [1]. At the 19th Communist Party of China National People’s Congress in September 2017, which described the Party’s strategic plans for the future decennia, the implementation of food safety strategy was stressed. At the same time, strive for higher quality of life gives rise to demands among consumers for higher quality of food. The most famous incident from the Chinese food industry remains the 2008 melamine milk scandal. It affected tens of thousands of children and multiple deaths of infants due to kidney failure [2]. -

Regulating China's Ecommerce: Harmonizations of Laws Pinghui Xiao Law School, Guangzhou University, China

Journal of Food Law & Policy Volume 14 | Number 2 Article 3 2018 Regulating China's Ecommerce: Harmonizations of Laws Pinghui Xiao Law School, Guangzhou University, China Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jflp Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, E-Commerce Commons, Food and Beverage Management Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Xiao, Pinghui (2018) "Regulating China's Ecommerce: Harmonizations of Laws," Journal of Food Law & Policy: Vol. 14 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jflp/vol14/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Food Law & Policy by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume Fourteen Number Two Fall 2018 REGULATING CHINA’S FOOD E-COMMERCE: HARMONIZATION OF LAWS Pinghui Xiao A PUBLICATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS SCHOOL OF LAW Regulating China’s Food E-commerce: Harmonization of Laws Pinghui Xiao* I. Introduction Internet commercialization began in China in 1995.1 Since then, China has seen a digitalization movement, which has become a joint undertaking between industry and government in the age of ubiquitous Internet in China.2 China’s Premier Li Keqiang announced ‘Internet Plus’ as the national strategy in his Government 3 Work Report presented during the Two Sessions of the year of 2015. * Dr. Pinghui Xiao is a senior lecturer at Law School, Guangzhou University, China and a recipient of the fellowship of the International Visitor Leadership Program awarded by the U.S. -

Vineyard Acreage Simulations in Consideration of Climatic Changes Affecting Rhineland-Palatinate (RLP)

38th World Congress of Vine and Wine (Part 1) BIO Web of Conferences Volume 5 (2015) Mainz, Germany 5-10 July 2015 Editor: Jean-Marie Aurand ISBN: 978-1-5108-0746-4 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ You are free to: Share – copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format. Adapt – remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercial. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. The copyright is retained by the corresponding authors. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2015) For additional information, please contact EDP Sciences – Web of Conferences at the address below. EDP Sciences – Web of Conferences 17, Avenue du Hoggar Parc d'Activité de Courtabœuf BP 112 F-91944 Les Ulis Cedex A France Phone: +33 (0) 1 69 18 75 75 Fax: +33 (0) 1 69 28 84 91 [email protected] Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2634 Email: [email protected] -

China Food Safety Legal and Regulatory Assessment

China Food Safety Legal and Regulatory Assessment Katrin Kuhlmann, Mengyi Wang, and Yuan Zhou1 March 2017 This Assessment is Part of a Series Under the China Food Safety Project Developed in Partnership Between the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture & the New Markets Lab I. Executive Summary The regulation of food safety in China has evolved in several stages, with growing comprehensiveness and cohesion resulting from successive rounds of legal and regulatory change. The formal concept of food safety took hold between 1984 and 2000. A top-down government oversight mechanism was fashioned, with the Ministry of Health (MOH) taking the chief responsibility for overall food safety control and the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA) responsible for the production of primary agricultural products. The first decade of the 21st century saw the emergence of a horizontal multi-ministry, production step control system, and a litany of food safety incidents, which unveiled oversight loopholes and severely undermined consumer confidence in domestic food. The most infamous example is the 2008 milk scandal, where an estimated 300,000 infants were fed milk contaminated with melamine. In response, China’s State Council promulgated special regulations and the Food Safety Law (2009) was passed, but food scares continued to plague the country. Poor inter-agency coordination, regulatory redundancy, overlapping and contradictory standards, and ineffective enforcement were highlighted as the primary challenges. Resolved to transform its food safety landscape, China has revamped its institutional and legal frameworks over the past five years. Institutionally, the creation of the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) in 2013 heralds an era of centralized food safety management, and CFDA enjoys vertical authority over food production, distribution, and consumption and falls within the oversight of the MOH. -

Past Research Projects Supervised by Faculty in SU Abroad Hong Kong Center – Updated in March 2019 Hong Kong • a Look At

Past Research Projects Supervised by Faculty in SU Abroad Hong Kong Center – Updated in March 2019 Hong Kong A Look at Hong Kong’s Legislative Council with American Perspective An Analysis of LP Lamma Holdings Limited An Investigation into the Future of Hong Kong International Film Festival Cha tea House Confucian Ethics and its Effects on Hong Kong Chinese Business Consumer Advertising for Hong Kong Segments Economic Crisis and Policy Response: A case study Economic of Housing I n Hong Kong Financial Analysis of sun Hung Kai Property Ltd Global Transaction Services in Depository Receipt for Citigroup History of Development of the Appreciation of Fast Food in the China Consume Market- HK History of Filmmaking in Hong Kong Hong Kong in the Asian Financial Crisis Housing in Hong Kong How is Human Resources Management in Hong Kong different from USA? Identifying Emerging Investment Opportunities within Hong Kong and Southern China Imperfect Information and Stock Market Price Volatility Investment in Hong Kong Marketing and the Film Industry (Hong Kong and USA) Personal Entrepreneurship in Hong Kong Retail in Hong Kong with a Concentration in the Cellular Phone Industry Smog, exhaust, and Poor Planning: Hong Kong’s pollution Problem The Business Environment in Hong Kong in the Context of Small and Medium Business Entrepreneurs The Future of the American Dollar The Important of Hong Kong in the Global Market The Pegged Hong Kong Exchange Rate in 1997 Asian Financial Crisis The Political Structure and Democratization -

A Study of the Dynamics of Regulation in China’S Dairy Industry

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details The Party-state, Business and a Half Kilo of Milk: A study of the dynamics of regulation in China’s dairy industry Sabrina Snell PhD Development Studies University of Sussex May 2014 3 UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX SABRINA SNELL PHD DEVELOPMENT STUDIES THE PARTY-STATE, BUSINESS AND A HALF KILO OF MILK: A STUDY OF THE DYNAMICS OF REGULATION IN CHINA’S DAIRY INDUSTRY SUMMARY This thesis examines the challenge of regulation in China’s dairy industry—a sector that went from being the country’s fastest growing food product to the 2008 melamine-milk incident and a nationwide food safety crisis. In this pursuit, it attempts to bridge the gap between analyses that view food safety problems through the separate lenses of the state regulatory apparatus and industry governance. It offers state-business interaction as a critical and fundamental component in both of these food safety mechanisms, particularly in the case of China where certain party-state activities can operate within industry chains. -

The Regulatory Regime of Food Safety in China, Studies in the Political Economy of Public Policy, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-50442-1 260 BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abels, Gabriele, and Alexander Kobusch. “Regulation of Food Safety in the EU: Changing Patterns of Multi-Level Governance.” In Conference of the ECPR Standing Group on Regulatory Governance. University College Dublin., 2010. ACFSMC. “Charter of All China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives (ACFSMC).” Xinhua Net, http://news.xinhuanet.com/ziliao/ 2004-12/27/content_2385266.htm. ADB, SFDA, and WHO. The Food Safety Control System of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: ADB, 2007. Agricultural Products Quality and Safety Center. “Major Responsibilities of Agricultural Products Quality and Safety Center.” Agricultural Products Quality and Safety Center, http://www.aqsc.agri.gov.cn/zhxx/zzjg/ 201012/t20101228_73068.htm. Agricultural Products Quality and Safety Supervision Department of MOA. “Major Responsibilities of Agricultural Products Quality and Safety Supervision Department of MOA.” Agricultural Products Quality and Safety Supervision Department of MOA, http://www.moa.gov.cn/sjzz/jianguanju/ jieshao/zhineng/201006/t20100606_1532739.htm. Anagnost, Ann. “From “Class” to Social Strata”: Grasping the Social Totality in Reform-Era China.” Third World Quarterly 29 (2008): 497–519. Anderlini, Jamil. “Chinese Police Cracked the Case of Adulterated Lamb.” Ftchinese, http://www.ftchinese.com/story/001050268. Anonymous. “China Is Working on the Methods to Detect Gutter Oil.” Beijing Times, 19 September 2011. ———. “The Ministry of Public Security Cracked Down a Major Case of Gutter Oil.” The Beijing News, 14 September 2011. © The Author(s) 2017 259 G. Zhou, The Regulatory Regime of Food Safety in China, Studies in the Political Economy of Public Policy, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-50442-1 260 BIBLIOGRAPHY Ansell, Christopher, and David Vogel.