Presentation in Teacher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bicycle Trips in Sunnhordland

ENGLISH Bicycle trips in Sunnhordland visitsunnhordland.no 2 The Barony Rosendal, Kvinnherad Cycling in SunnhordlandE16 E39 Trondheim Hardanger Cascading waterfalls, flocks of sheep along the Kvanndal roadside and the smell of the sea. Experiences are Utne closer and more intense from the seat of a bike. Enjoy Samnanger 7 Bergen Norheimsund Kinsarvik local home-made food and drink en route, as cycling certainly uses up a lot of energy! Imagine returning Tørvikbygd E39 Jondal 550 from a holiday in better shape than when you left. It’s 48 a great feeling! Hatvik 49 Venjaneset Fusa 13 Sunnhordland is a region of contrast and variety. Halhjem You can experience islands and skerries one day Hufthamar Varaldsøy Sundal 48 and fjords and mountains the next. Several cycling AUSTE VOLL Gjermundshavn Odda 546 Våge Årsnes routes have been developed in Sunnhordland. Some n Husavik e T YS NES d Løfallstrand Bekkjarvik or Folgefonna of the cycling routes have been broken down into rfj ge 13 Sandvikvåg 49 an Rosendal rd appropriate daily stages, with pleasant breaks on an a H FITJ A R E39 K VINNHER A D express boat or ferry and lots of great experiences Hodnanes Jektavik E134 545 SUNNHORDLAND along the way. Nordhuglo Rubbestad- Sunde Oslo neset S TO R D Ranavik In Austevoll, Bømlo, Etne, Fitjar, Kvinnherad, Stord, Svortland Utåker Leirvik Halsnøy Matre E T N E Sveio and Tysnes, you can choose between long or Skjershlm. B ØMLO Sydnes 48 Moster- Fjellberg Skånevik short day trips. These trips start and end in the same hamn E134 place, so you don’t have to bring your luggage. -

Næringsanalyse Stord, Fitjar Og Sveio

Næringsanalyse Stord, Fitjar og Sveio Av Knut Vareide og Veneranda Mwenda Telemarksforsking-Bø Arbeidsrapport 35/2007 ____________________Næringsanalyse Stord, Fitjar og Sveio_____________ Forord Denne rapporten er laget på oppdrag fra SNU AS. Hensikten var å få fram utviklingen i næringslivet i kommunene Stord, Fitjar og Sveio. Telemarksforsking-Bø har i de siste årene publisert næringsNM for regioner, hvor vi har rangert næringsutviklingen i regionene i Norge. I dette arbeidet er det konstruert en næringslivsindeks basert på fire indikatorer: Lønnsomhet, vekst, nyetableringer og næringstetthet. Oppdragsgiver ønsket å få belyst utviklingen av næringslivsindeksen og delindikatorene for de tre aktuelle kommunene. Når det gjelder indikatorene for vekst og lønnsomhet, er disse basert på regnskapene til foretakene. Disse er tilgjengelige i september i det etterfølgende året. Dermed er det tallene for 2005 som er benyttet i næringslivsindeksen i denne rapporten. Vi har likevel tatt med tall for nyetableringer i 2006 i denne rapporten, ettersom disse er tilgjengelige nå. I næringslivsindeksen er det imidlertid etableringsfrekvensen for 2005 som er telt med. Bø, 6. juni 2007 Knut Vareide 2 ____________________Næringsanalyse Stord, Fitjar og Sveio_____________ Innhold: ¾ Lønnsomhet Stord ..........................................................................................................................5 ¾ Vekst Stord ......................................................................................................................................6 -

Vestland County a County with Hardworking People, a Tradition for Value Creation and a Culture of Cooperation Contents

Vestland County A county with hardworking people, a tradition for value creation and a culture of cooperation Contents Contents 2 Power through cooperation 3 Why Vestland? 4 Our locations 6 Energy production and export 7 Vestland is the country’s leading energy producing county 8 Industrial culture with global competitiveness 9 Long tradition for industry and value creation 10 A county with a global outlook 11 Highly skilled and competent workforce 12 Diversity and cooperation for sustainable development 13 Knowledge communities supporting transition 14 Abundant access to skilled and highly competent labor 15 Leading role in electrification and green transition 16 An attractive region for work and life 17 Fjords, mountains and enthusiasm 18 Power through cooperation Vestland has the sea, fjords, mountains and capable people. • Knowledge of the sea and fishing has provided a foundation Experience from power-intensive industrialisation, metallur- People who have lived with, and off the land and its natural for marine and fish farming industries, which are amongst gical production for global markets, collaboration and major resources for thousands of years. People who set goals, our major export industries. developments within the oil industry are all important when and who never give up until the job is done. People who take planning future sustainable business sectors. We have avai- care of one another and our environment. People who take • The shipbuilding industry, maritime expertise and knowledge lable land, we have hydroelectric power for industry develop- responsibility for their work, improving their knowledge and of the sea and subsea have all been essential for building ment and water, and we have people with knowledge and for value creation. -

The Impact of Pecuniary Costs on Commuting Flows

INSTITUTT FOR FORETAKSØKONOMI DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCE FOR 4 2010 ISSN: 1500-4066 MAY 2010 Discussion paper The impact of pecuniary costs on commuting flows BY DAVID PHILIP McARTHUR, GISLE KLEPPE, INGE THORSEN, AND JAN UBØE The impact of pecuniary costs on commuting flows∗ David Philip McArthur,y Gisle Kleppe z, Inge Thorsen,x and Jan Ubøe{ Abstract In western Norway, fjords cause disconnections in the road network, necessitating the use of ferries. In several cases, ferries have been replaced by roads, often part-financed by tolls. We use data on commuting from a region with a high number of ferries, tunnels and bridges. Using a doubly-constrained gravity-based model specification, we focus on how commuting responds to varying tolls and ferry prices. Focus is placed on the role played by tolls on infrastructure in inhibiting spatial interaction. We show there is considerable latent demand, and suggest that these tolls contradict the aim of greater territorial cohesion. 1 Introduction The presence of topographical barriers like mountains and fjords often cause disconnections in the road network. In coastal areas of western Norway some large-scale investments have been carried through that remove the effect of such barriers through the construction of bridges and tunnels. Other road infrastructure investments are being planned, connecting areas that, in a Norwegian perspective, are relatively densely populated. Economic evaluations of such investments call for predictions of generated traffic, and the willingness-to-pay for new road connections. This paper focuses on commuting flows, which represent one important component of travel demand. In most cases, a new tunnel or bridge is at least partly financed by toll charges. -

Virksomheter Som Omsetter Vertplanter for Pærebrann I Pærebrannsona Eller Bekjempelsessona (Fylkesnavn Og Kommunenavn Er Iht

Virksomheter som omsetter vertplanter for pærebrann i pærebrannsona eller bekjempelsessona (Fylkesnavn og kommunenavn er iht. kommunesammenslåing og regionreform pr. 1/1/2020, dvs. lista er iht. endringsforskrift fastsatt i april 2020.) Fylke Kommune Virksomhetsnavn Beliggenhetsadresse Møre og Romsdal Ålesund PLANTASJEN AVD ÅLESUND Holen, 6019 Ålesund Møre og Romsdal Ålesund VIDDALS GARTNERI Brusdalsvegen 304, 6011 Ålesund Møre og Romsdal Ålesund UTGÅRD SERVICE Ellingsøy Møre og Romsdal Ålesund GJÆRDES GARTNERI OG PLANTESKOLE Gjærdevegen, 6010 Ålesund Møre og Romsdal Ålesund FELLESKJØPET AGRI Postvein 11, 6018 Ålesund Møre og Romsdal Herøy PEKAS (PER IGESUND AS) 6092 Fosnavåg Møre og Romsdal Volda PLANTASJEN AVD VOLDA Furene, 6105 Volda Møre og Romsdal Volda TILSETH HAGESENTER AS Furene, 6105 Volda Vestland Askvoll KLOKKERNES INGELING Prestemarka 33, 6980 Askvoll Vestland Alver EIKANGER HAGESENTER AS Sauvågen 251, 5913 Eikangervåg Vestland Alver SØDERSTRØM BLOMSTER OG HAGESENTER AS Lyngvegen 1, 5914 Isdalstø Vestland Øygarden RENNEDAL GARTNERI Nils Ståle Renned Rennedal, 5355 Knarrevik Vestland Øygarden SOTRA HAGESENTER AS Gjertrudvegen 3, 5353 Straume Vestland Askøy ASKØY HAGESENTER AS Juvikflaten, 5300 Kleppestø Vestland Askøy EIDES STAUDER Abbedissevegen 73, 5314 Kjerrgarden Vestland Askøy FRUDALEN HAGESENTER AS Erdalsvegen 79, 5306 Erdal Vestland Askøy PLANTASJEN NORGE AS AVD ASKØY Ravnanger Senter, 5310 Hauglandshella Vestland Bergen TOPPE GARTNERI Nils Gunnar Toppe Toppevegen 85, 5136 Mjølkeråen Vestland Bergen KILDEN HAGESENTER -

Araucaria Araucana in West Norway*

petala (Rosaceae), an interesting dwarf subshrub. This has pinnate dentate leaves, decorative fruits, and large single white flowers borne about 15 cm above the ground. Another attractive shrub in this area is Myrica tomentosa, related to the European M. gale. This grows to about 1m high, has a characteristic resinous smell and flowers before the pubescent young shoots and leaves appear. Also here are numerous tiny orchids of the genera Hammarbya, Platanthera, and Listera, which in most parts of Europe are rare or endangered, and, on the black beach, the pale blue, funnel-shaped flowers of Mertensia maritima. On the shores of Lake Nachikinsky (360 m above sea level) we had an unforgettable view of thousands of bright red, spawning sockeye salmon. From here we travelled on to the eastern, Pacific coast of Kamchatka, where the sand on the deserted beach was almost black, and the water considerably warmer than on the west coast. Here we camped behind a range of low semi-overgrown sandy dunes, which ran parallel to the ocean prior to merging inland into a large flat plain with heath-like vegetation, with tundra and aquatic species, especial- ly along streams and in hollows. This was the only place where we found Rosa rugosa, growing among scattered bushes of Pinus pumila. We ended our expedition high in the mountains, on the slopes of the Avachinsky and Korjaksky volcanoes, where perennial snowfields gave rise to numerous streams, an uncommon sight in the volcanic landscape of Kamchatka. Here, well above the tree line, the flora was again decidedly alpine, and this was the only place where we encoun- tered the unusual evergreen dwarf ericaceous shrub, Bryanthus gmelinii, with spikes of small pink flowers. -

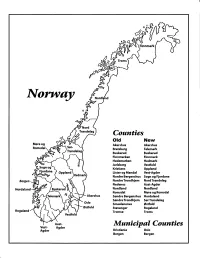

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Rødlistearter I Stord Og Fitjar, Samt Litt Generelt Om Natur Og Sjeldne

Rødlistearter i Stord og Fitjar, samt litt generelt om natur og sjeldne naturtyper i Sunnhordland Per Fadnes Høgskolen på Vestlandet Rødlistearter i Stord og Fitjar samt litt generelt om natur og sjeldne naturtyper i Sunnhordland 1 2017 Takk til Arne Vatten som har gitt oppdatert informasjon om fuglefaunaen på Stordøya. Alle bildene er tatt av forfatteren med unntak av Havburkne, fagerrogn, brunskjene og gul pærelav som er tatt av Asbjørn Knutsen og Pusleblom, steinstorkenebb, alm og ask som er tatt av Jan Rabben. Kartutsnittene er tatt fra Artskart, Artsdatabanken. Forsidebilde: Soleigro Baldellia repens, Flammevokssopp Hygrocybe intermedia og gul pærelav Pyrenula occidentalis. Rødlistearter i Stord og Fitjar samt litt generelt om natur og sjeldne naturtyper i Sunnhordland 2 Innhold Innleding.............................................................................................................................................4 Rødlisten 2015....................................................................................................................................4 Vegetasjonssoner i Sunnhordland .......................................................................................................6 Geologi og topografi ..........................................................................................................................7 Sunnhordland et plantegeografisk møtepunkt ..................................................................................7 Viktige og sjeldne naturtyper i Sunnhordland ................................................................................... -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Oversyn Over Ledige Skuleplassar I Vestland Fylke Pr 9

Oversyn over ledige skuleplassar i Vestland fylke Pr 9. august 2021 Merk at alle må møte opp på den skulen dei allereie har fått plass på. Ønskjer du ein av dei ledige plassane under, må du ta kontakt med den skulen du ønskjer plass på. Oversynet er rettleiande, og blir ikkje oppdatert etter kvart som dei ledige plassane blir fordelte til interesserte søkjarar. Vidaregåande kurs 1 Skule Programområde Utdannings- program Austrheim vidaregåande skule Bygg- og anleggsteknikk BA Dale vidaregåande skule Bygg- og anleggsteknikk BA Flora vidaregåande skule Bygg- og anleggsteknikk BA Odda vidaregåande skule Bygg- og anleggsteknikk BA Flora vidaregåande skule Elektro og datateknologi EL Fitjar vidaregåande skule Frisør, blomster, interiør og eksponeringsdesign FD Voss gymnas Frisør, blomster, interiør og eksponeringsdesign FD Austevoll vidaregåande skule Helse- og oppvekstfag HS Austrheim vidaregåande skule Helse- og oppvekstfag HS Kvam vidaregåande skule Helse- og oppvekstfag HS Kvinnherad vidaregåande skule Helse- og oppvekstfag HS Odda vidaregåande skule Helse- og oppvekstfag HS Osterøy vidaregåande skule Helse- og oppvekstfag HS Voss gymnas Helse- og oppvekstfag HS Flora vidaregåande skule Idrettsfag ID Stord vidaregåande skule Idrettsfag ID Voss gymnas Idrettsfag ID Fusa vidaregåande skule Kunst, design og arkitektur KD Hafstad videregående skule Kunst, design og arkitektur KD Voss gymnas Kunst, design og arkitektur KD Firda vidaregåande skule Musikk, dans og drama,dans MD Langhaugen videregående skole Musikk, dans og drama,dans MD Fyllingsdalen -

The Original Twin Screw Press for the Seafood Processing Industries

Stord PUTSCH® GROUP The Original Twin Screw Press for the Seafood Processing Industries Newly designed Screw Press L72-F • Press cake with high dry substance percentage • High recovery of liquids • Reliable operation • Robust design • Long life - low maintenance • Energy effi cient Stord PUTSCH® GROUP The best investment for effi cient dewatering in the seafood processing industries For separation of liquids from pro- The spindles rotate in opposite The press is encased by stainless cessed seafood, the Stord Twin directions, which prevents the steel covers with easily detach- Screw Presses are the best ma- fi sh mass from rotating with the able side doors for inspection of chines available on the market. spindles. The shaft of each spindle the strainer cages. The covers Stord Twin Screw Presses are avail- is supported by spherical roller bear- are tightened against the frame of able in nominal capacities ranging ings. The press’ cages is built up in the press, thus preventing vapor from 2.5 to 60 tons of raw material sections. Each section consists of from escaping the press cage and per hour; under certain conditions perforated stainless steel strainer making it easy to fully deodorize the even higher capacities are obtain- plates with diff erent hole sizes. press by connecting it to the suction able. The design of the press is system of a deodorizing plant. based upon a thorough examination The horizontal design allows easy The press can be supplied with a of the structure and pressability of access to all parts of the press. By cleaning system for cleaning of the practically all types of seafood raw removing the covers, loosening the strainer plates during operation. -

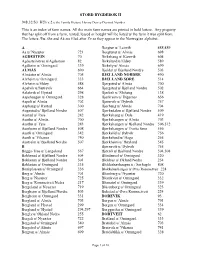

STORD BYGDEBOK II This Is an Index of Farm Names. All the Main Farm

STORD BYGDEBOK II 948.32/S3 H2h v.2 is the Family History Library Dewey Decimal Number This is an index of farm names. All the main farm names are printed in bold letters. Any property that has split off from a farm, rented, leased or bought will be listed u/ the farm it was split from. The letters Ææ, Øø and Åå are filed after Zz as they appear in the Norwegian alphabet. A Bergtun u/ Leirvik 488,489 Aa u/ Nysæter 721 Bergtunet u/ Almås 698 AGDESTEIN 70 Birkehaug u/ Kårevik 604 Agdesteinstrae u/Agdestein 82 Birkelund u/Eldøy 589 Agdheim u/ Orningard 339 Birkely u/ Almås 699 ALMÅS 690 Bjeldal u/ Bjelland Nordre 503 Almåstre u/ Almås 705 BJELLAND NORDRE 490 Alvheim u/ Orningard 333 BJELLAND SØRE 514 Alvheim u/Eldøy 588 Bjergsted u/ Almås 700 Apalvik u/Sætrevik 664 Bjergsted u/ Bjelland Nordre 502 Aslakvik u/ Hystad 298 Bjerkeli u/ Slohaug 138 Aspehaugen u/ Orningard 328 Bjerkreim u/ Digernes 656 Aspeli u/ Almås 702 Bjønnvik u/ Dybvik 757 Asphaug u/ Hystad 300 Bjørhaug u/ Almås 704 Augestad u/ Bjelland Nordre 507 Bjørkedalen u/ Bjelland Nordre 509 Austad u/ Tyse 242 Bjørkehaug u/ Dale 419 Austbø u/ Almås 700 Bjørkehaugen u/ Almås 703 Austbø u/ Tyse 243 Bjørkehaugen u/ Bjelland Nordre 506,512 Austheim u/ Bjelland Nordre 508 Bjørkehaugen u/ Tveita Søre 556 Austli u/ Orningard 342 Bjørkelid u/ Dybvik 756 Austli u/ Vikanes 740 Bjørkelund u/ Haga 265 Austreim u/ Bjelland Nordre 507 Bjørkheim u/ Høyland 545 B Bjørnevik u/ Dybvik 755 Bagga-Trae u/ Langeland 567 Bjørnli u/ Bjelland Nordre 504,508 Bakkerud u/ Bjelland Nordre 504 Blindensol u/ Orningard