Chilean Antitrust Policy: Some Lessons Behind Its Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literacy and Deaf Education: Toward a Global Understanding (Contributors)

Contributors Abdulhadi A. Alamri Kleopatra Diakogiorgi Special Education Department, Prince Department of Education and Social Sattam bin Abdulaziz University Work, University of Patras Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia Patras, Greece Ghithan S. Alamri Luz Mary Lpez Franco Special Education Department, Taibah Department of Social and Human University Development, Specialized Medina, Saudi Arabia University of the Americas Panama City, Panama Farraj Alqarni Adults Teaching Department, Department of Special Education, Comfamiliar Risaralda School Jouf University Pereira, Colombia Aljouf, Saudi Arabia Cátia de Azevedo Fronza Ahmed Alzahrani Graduate Program in Applied Special Education Department, Linguistics, University of Vale do Majmaah University Rio dos Sinos Majmaah, Saudi Arabia São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil Fabiola Ruiz Bedolla Barbara Gerner de Garcia National Council for Development and Department of Education, Gallaudet Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities University (Consejo Nacional para el Desarrollo Washington, DC, USA y la Inclusin de las Personas con Discapacidad) Debbie Golos Mexico City, Mexico Department of Educational Psychology, University of Sarah Boehm Minnesota Arizona State Schools for the Deaf Minneapolis, MN, USA and the Blind Tucson, AZ, USA Catalina Henríquez Department of Psychology, Pontifcal Joanna E. Cannon Catholic University of Chile Department of Educational & (Pontifcia Universidad Catlica Counselling Psychology & Special de Chile) Education, the University of British Santiago, Chile Columbia Vancouver, British Columbia, -

2 March 2020 Errata in the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) Handled in Accordance W

2 March 2020 Errata in the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) Handled in accordance with the IPCC protocol for addressing possible errors in IPCC Assessment Reports, Synthesis Reports, Special Reports and Methodology Reports: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/09/ipcc_error_protocol_en.pdf Summary for Policymakers A.3.1, Line 1: Replace '1902–2015' with '1902–2010' and replace 'likely' with 'very likely' Chapter 1 Figure 1.1: Replace Figure 1.1 with Errata Figure 1.1. Panel f equation given as 'FAR = 1 – Pant / Pnat' has been corrected to read 'FAR = 1 – Pnat / Pant' Figure 1.1 Caption, Line 11, replace 'FAR = 1 – Pant / Pnat' with 'FAR = 1 – Pnat / Pant' Chapter 3 Figure 3.3: Replace Figure 3.3 with Errata Figure 3.3. The sea ice concentration trend unit ‘°C per decade’ has been corrected to read '% per decade' Annex IV Annex IV: List of Expert Reviewers: the following entries to be added, incorporated alphabetically by surname: AHO, Kelsey BOLLIGER, Ian CARTER, Natalie University of Alaska Fairbanks University of California, Berkeley University of Ottawa USA USA Canada AMIRI, Azita BRADLEY, Alice CHALK, Thomas Iran Meteorological Organization University of Colorado Boulder University of Southampton Iran USA United Kingdom ANDREWS, Lauren BROOKS, Heather CHAMBERS, Catherine NASA Goddard Space Flight Université Laval University Centre of the Center Canada Westfjords USA Iceland BURDETT, Heidi BENNETT, Mia Heriot-Watt University CHAMPOLLION, Nicolas The University of Hong Kong United -

What Is a Doctorate? CGS Acknowledges the Generous Support of Our Sponsor for the 2016 Strategic Leaders Global Summit: Table of Contents

Tenth Annual Strategic Leaders Global Summit on Graduate Education November 15-17, 2016 University of São Paulo Brazil What Is a Doctorate? CGS acknowledges the generous support of our sponsor for the 2016 Strategic Leaders Global Summit: Table of Contents 2016 Strategic Leaders Global Summit on Graduate Education: Agenda Papers Introduction Suzanne T. Ortega, Council of Graduate Schools 10 1: Current and Evolving Definitions of the Doctorate Presented Papers Hans-Joachim Bungartz, Technical University of Munich 14 Denise Cuthbert, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University 17 Susan Porter, University of British Columbia 20 Mark J.T. Smith, Purdue University 23 Shireen Motala, University of Johannesburg 26 Brenda Yeoh, National University of Singapore 30 2: Doctoral Admissions and Recruitment: Assessing Readiness to Pursue Doctoral Study David G. Payne, Educational Testing Service 36 Adham Ramadan, American University in Cairo 39 Yaguang Wang, Shanghai Jiao Tong University 42 Kate Wright, University of Western Australia 44 3: Doctoral Mentoring & Supervision Vahan Agopyan, University of São Paulo 48 Mee-Len Chye, The University of Hong Kong 50 Richard (Dick) Strugnell, University of Melbourne 52 Tao Tao, Xiamen University 56 Qiang Yao, Tsinghua University 59 4: Career Preparation & Innovations in Doctoral Curricula and Training Jani Brouwer, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile 62 Karen Butler-Purry, Texas A&M University 64 Barbara Crow, York University 66 5: Doctoral Dissertations and Capstones Marie Audette, Laval University 68 Alastair McEwan, University of Queensland 71 Christopher Sindt, Saint Mary’s College of California 74 6: How Do Doctoral Assessment & Career Tracking Influence Definitions of Doctoral Education? Philippe-Edwin Bélanger, Université du Québec 78 Luke Georghiou, University of Manchester 80 Barbara A. -

Urbanisation, Planning & Development Cluster

DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENT – PHD DESTINATIONS Private Sector Academia Research for public and third sector, and international organisations Burohappold Tec de Monterrey (Associate Prof.) Indian Institute for Human Settlements Engineering, New York Di Tella University (Prof.) Fondation Rio Tinto University of Antioquia, Medellin (Assistant Prof.) Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research University of Endinburgh and the Open University (Innogen Post-Doc) Regional Government of Sardegna University of York (Post-Doc) UK Equality and Human Rights University of Salford (Lecturer) Commission Cambridge University (Lecturer) IIED Direct on Womens' Economic Empowerment and Humanitarian Aid in Oxford University (Post-Doc) Kathmandu Valley Loughborough University (Vice Chancellor’s Research Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner Fellow) Renmin University of China (Assistant Professor) Economic Development & Property, Urbanisation, Planning & Urbanisation, Development Cluster Horsham District Council Monash University of Malaysia (Senior Lecturer) InterAmerican Development Bank Universidad Católica de Chile (Post-doc) Post-Doc at Universidad Catolica de Chile Lancaster University (Post-Doc) London School of Economics (Teaching Fellow) Lectureship in Development Planning for Diversity at the the Bartlett, Development Planning Unit (UCL) ESRC Postdoctoral Research Fellow, LSE Private Sector Academia Research for public and third sector, and international organisations University of Virginia Flowminder Foundation, Stockholm Amec Forest -

Curriculum Vitae Fernanda S. Valdovinos 04/17/2019

Curriculum Vitae Fernanda S. Valdovinos Curriculum Vitae Fernanda S. Valdovinos Assistant Professor Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Center for the Study of Complex Systems University of Michigan 1105 North University Ave, Biological Sciences Building Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA [email protected] / www.fsvaldovinos.com EDUCATION 2009-2014 PhD in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Chile 2008 Professional degree in Environmental Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Chile. (similar to a professional M.S. in the U.S.A.) 2004-2007 Licenciatura in Environmental Science w/ Biology concentration, Faculty of Science, University of Chile. (similar to B.S. in the U.S.A.) POSITIONS 2018-present Assistant Professor of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. 2018-present Assistant Professor of Complex Systems, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. 2014-2017 Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ. 2013 Research Assistant, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ. 2013 Research Assistant, Pacific Ecoinformatics & Computational Ecology Lab, Berkeley, CA. 2012 Research visitor, Pacific Ecoinformatics & Computational Ecology Lab, Berkeley, CA. 2012 Research visitor, Estación Biológica de Doñana, CSIC, Spain. GRANTS & AWARDS 2018 NSF Collaborative Research: “RAPID: re-wiring of montane pollination networks under severe drought stress” DEB-1834487. $200,000 (UM $44,369) 2018 MICDE Catalyst Grant: “Embedded Machine Learning Systems To Sense and Understand Pollinator Behavior” U061182, The Michigan Institute for Computational Discovery & Engineering (MICDE), University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. $90,000 2012 Fellowship for research stays abroad for PhD students, Becas-Chile, Government of Chile. -

OFER MALAMUD Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies Work Phone

OFER MALAMUD Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies Work phone: 773-702-2389 University of Chicago Fax: 773-702-0926 1155 East 60th Street Email: [email protected] Chicago, IL 60637 Employment and Affiliations Associate Professor, Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago, 2013–present Assistant Professor, Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago, 2004–2013 Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), 2013–present Faculty Research Fellow, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), 2008–2013 Research Associate, Population Research Center, Chicago and NORC, 2004–present Faculty Affiliate, Center for Human Potential and Public Policy (CHPPP), 2005–present Education Ph.D., Economics, Harvard University, 2004 M.A., Economics, Harvard University, 2002 B.A., Economics and Philosophy, Harvard University, 1997 Published and Forthcoming Papers “Is College a Worthwhile Investment?” (with Lisa Barrow). Annual Review of Economics Vol. 7 (2015): 519–55 “One Laptop Per Child at Home: Short-Term Impacts from a Randomized Experiment in Peru” (with Diether Beuermann, Julian Cristia, Yyannu Cruz-Aguayo, and Santiago Cueto). American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 7, No. 2 (2015): 1-29 “The Impact of Class-Based Affirmative Action on Admission and Academic Outcomes in Israel,” (with Sigal Alon). Economics of Education Review, Vol. 40 (2014): 123-139 “Self-Selection and International Migration: New Evidence from Mexico,” (with Robert Kaestner). Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 96, No. 1 (2014): 78-91 “The Impact of College Education on Migration: Evidence from the Vietnam Generation,” (with Abigail Wozniak). Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 47, No. 4 (2012): 913-950 “School Tracking on Access to Higher Education among Disadvantaged Groups,” (with Cristian Pop-Eleches). -

USYD Global Mobility Guide

2020 edition Global Mobility Guide Global MobilityGlobal Guide 2020 edition Why study overseas? �������������������������������������� 2 Our global mobility programs �����������������������4 Getting credit towards your course �������������9 How to apply �������������������������������������������������� 10 Our Super Exchange Partners ���������������������14 Where can I study? ����������������������������������������16 Scholarships and costs ��������������������������������22 Global Citizenship Award�����������������������������26 What’s next? ��������������������������������������������������28 #usydontour FAQs �����������������������������������������������������������������31 “Just two words: DO IT. I have not met one person who has regretted their overseas experience. It is simply not possible to live/ study overseas without gaining something out Why study overseas? of it. Whether it is new friends or important lessons learned. Usually both! Living and studying overseas is a once in a lifetime The University of Sydney has the largest global student opportunity that will change you for the better.” mobility program in Australia*� Combine study and travel to Yasmin Dowla Bachelor of Arts/Bachelor of Economics broaden your academic experience and set yourself up for University of Edinburgh, Scotland a global career� Develop the cultural competencies to work across borders, while having the experience of a lifetime� sydney.edu.au/study/overseas-programs Develop your Experience new self-confidence, ways of learning Gain a Over independence -

2020 GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS He Benefits Attached to an MBA Weighting of Data Points (Full-Time and Part-Time MBA)

2020 GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS he benefits attached to an MBA Weighting of Data Points (full-time and part-time MBA) are well documented: career Quality of Faculty: 34.95 % progression, networking International Diversity: 9.71% opportunities, personal Tdevelopment, salary... and the list Class Size: 9.71% goes on. However, in an increasingly Accreditation: 8.74% congested market, selecting the right Faculty business school can be difficult, which to Student Ratio: 7.76% is far from ideal given the time and Price: 5.83% investment involved. International Exposure: 4.85% Using a ranking system entirely geared and weighted to fact-based Work Experience: 4.85% *EMBA Weighting: Professional Work experience and criteria, CEO Magazine aims to cut Development: 4.85% international diversity are through the noise and provide potential adjusted accordingly. Gender Parity: 4.85% students with a performance benchmark **Online MBA Weighting: Delivery methods: 3.8% for those schools under review. Delivery mode and class 0 % 5 % 10 % 15 % 20 % 25 % 30 % 35 % size are removed. GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS TIER ONE Business School Country Business School Country AIX Marseille Graduate School of Management Monaco Emlyon Business School France American University: Kogod North America ESADE Business School Spain Appalachian State University* North America EU Business School Germany, Spain Ashland University North America and Switzerland Aston Business School UK Florida International University North America Auburn University: Harbert North America Fordham University North -

Brief Facts on Chile

Teaching • Research • Outreach Relevant Data Santiago de Chile - 2008 www.uchile.cl Brief Facts on Chile Location: Southeastern Latin America. • Founded on November 19, 1842. Among its first Presidents, it is important to mention the Venezuelan humanist and jurist Prof. Surface Area (continental & insular): 756,247 km2. Andrés Bello (1843-1865), and the Polish scientist and mineralogist Capital: Santiago. Prof. Ignacio Domeyko (1867-1883). Government: Representative Democracy. • Located in Santiago, Presidential Regime. Secular State. • 19 Chilean Presidents (61% of the total number) have been University Population: 16,598,074. of Chile alumni. Number of Students in Higher Education: • The two Chileans Nobel Prize awarded in Literature - Gabriela Mistral 650,000, representing 37% of young people between (1945) and Pablo Neruda (1971) were members of the University of 18 and 24 years. Chile. Institutions of Higher Education: • 142 National Prizes in different fields (83% of the total) have been 16 Public Universities. awarded to distinguished persons that have been alumni, and are 47 Private Universities (9 of them receive financial or were professors or researchers at the University of Chile. aid from Government). It is ranked among the best 500 universities in the World University 42 Professional Institutes. • Ranking (Shanghai Jiao Tong University) and in sixth place among 89 Technical Centers. the Latin American universities in the Research Institutions Ranking Official Language: Spanish. (SCImago Research Group, Spain). Official Currency: Chilean Peso (for exchange rate, • Students see: www.bcentral.cl). - Undergraduate Students: 24,465. Admission system: selection through a national admission test. Average minimum reference score for admission: 688, in a standard scale from 200 to 800 points. -

2020 JMK Schools

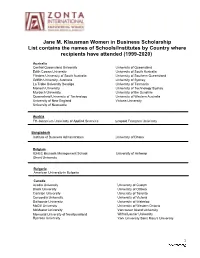

Jane M. Klausman Women in Business Scholarship List contains the names of Schools/Institutes by Country where recipients have attended (1999-2020) Australia Central Queensland University University of Queensland Edith Cowan University University of South Australia Flinders University of South Australia University of Southern Queensland Griffith University, Australia University of Sydney La Trobe University Bendigo University of Tasmania Monash University University of Technology Sydney Murdoch University University of the Sunshire Queensland University of Technology University of Western Australia University of New England Victoria University University of Newcastle Austria FH-Joanneum University of Applied Sciences Leopold Franzens University Bangladesh Institute of Business Administration University of Dhaka Belgium ICHEC Brussels Management School University of Antwerp Ghent University Bulgaria American University in Bulgaria Canada Acadia University University of Guelph Brock University University of Ottawa Carleton University University of Toronto Concordia University University of Victoria Dalhousie University University of Waterloo McGill University University of Western Ontario McMaster University Vancouver Island University Memorial University of Newfoundland Wilfrid Laurier University Ryerson University York University Saint Mary's University 1 Chile Adolfo Ibanez University University of Santiago Chile University of Chile Universidad Tecnica Federico Santa Maria Denmark Copenhagen Business School Technical University of Denmark -

Seti 2019 Program Contributors

SETI 2019 PROGRAM CONTRIBUTORS Gloria Afful-Mensah Gloria holds a PhD degree in economics from the University of Milan; Master of Philosophy degree in economics; and Bachelor of Arts degree in economics with geography and resource development, both from the University of Ghana. Gloria is currently a Research Associate with the Agenda for International Development and an “Adjunct Lecturer” at the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration. Gloria has a strong interest in empirical microeconomics, particularly issues concerning and/or related to health outcomes. She is also passionate about issues related to economic development and policy evaluation. Shalu Agrawal Shalu Agrawal is a policy researcher, working as Programme Lead at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, an independent not-for- profit policy think-tank based in New Delhi. Her research interests revolve around energy access, rural electrification and clean energy transition. She has also worked on policy issues in areas of renewable energy deployment and fossil fuel subsidies reform. She has been associated with the Initiative on Sustainable Energy Policy (Johns Hopkins SAIS) and Smart Power India. She is a policy specialist and an electrical engineer by training, educated at the University College London and Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee. Rex Alirigia I am second year Environmental studies graduate student at the university of Colorado, Boulder. My research interest is studying the effects of biomass fuels and clean cookstoves technologies in energy poverty regions. My recent work is a collaborative research with the university of Colorado, Navrongo health research center to investigate the Prices, Peers & Perception (P3) for improved biomass cookstoves in Northern Ghana. -

2018 Global Mba Rankings

2018 GLOBAL MBA RANKINGS Weighting of Data Points (full-time and part-time MBA) he benefits attached to an MBA are well documented: career Quality of Faculty: 34.95 % progression, networking International Diversity: 9.71% opportunities, personal Class Size: 9.71% Tdevelopment, salary... and the list goes on. However, in an increasingly Accreditation: 8.74% Faculty congested market, selecting the right to Student Ratio: 7.76% business school can be difficult, which Price: 5.83% is far from ideal given the time and investment involved. International Exposure: 4.85% Using a ranking system entirely Work Experience: 4.85% *EMBA Weighting: geared and weighted to fact-based Work experience and Professional 4.85% criteria, CEO Magazine aims to cut Development: international diversity are adjusted accordingly. through the noise and provide potential Gender Parity: 4.85% **Online MBA Weighting: students with a performance benchmark Delivery methods: 3.8% Delivery mode and class for those schools under review. 0 % 5 % 10 % 15 % 20 % 25 % 30 % 35 % size are removed. NORTH AMERICAN MBA RANKINGS TIER ONE American University: Kogod Saint Mary's College of California Appalachian State University Seattle University: Albers Auburn University: Harbert Suffolk University Bentley University: McCallum Temple University: Fox Boston University: Questrom Texas A&M University- College Station: Mays Bryant University Texas Christian University: Neeley California State University- Chico University of Akron California State University- Long Beach University of Alberta