Shrinking Space and the BDS Movement | 3 Shrinking Space and the BDS Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Legal Document

Case: 18-16896, 01/22/2019, ID: 11161862, DktEntry: 69, Page 1 of 26 No. 18-16896 ___________________________________________________________ IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT ___________________________________________________________ MIKKEL JORDAHL and MIKKEL (MIK) JORDAHL, P.C., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. THE STATE OF ARIZONA and MARK BRNOVIC, ARIZONA ATTORNEY GENERAL, Defendants-Appellants, and JIM DRISCOLL, COCONINO COUNTY SHERIFF, et al., Defendants. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Arizona Case No. 3:17-cv-08263 ___________________________________________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE, AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE, ISRAEL PALESTINE MISSION NETWORK OF THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH (USA), A JEWISH VOICE FOR PEACE, INC., US CAMPAIGN FOR PALESTINIAN RIGHTS, US PALESTINIAN COMMUNITY NETWORK, US CAMPAIGN FOR THE ACADEMIC AND CULTURAL BOYCOTT OF ISRAEL AND FRIENDS OF SABEEL NORTH AMERICA, IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS AND AFFIRMANCE ___________________________________________________________ JETHRO M. EISENSTEIN PROFETA & EISENSTEIN 45 Broadway, Suite 2200 New York, New York 10006 (212) 577-6500 Attorneys for Amici Curiae ___________________________________________________________ Case: 18-16896, 01/22/2019, ID: 11161862, DktEntry: 69, Page 2 of 26 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT A Jewish Voice for Peace, Inc. has no parent corporations. It has no stock, so therefore no publicly held company owns 10% or more of its stock. The other amici joining in this brief are -

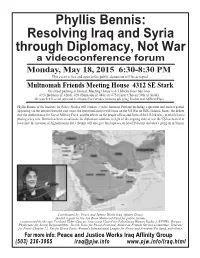

Phyllis Bennis

Phyllis Bennis: Resolving Iraq and Syria through Diplomacy, Not War a videoconference forum Monday, May 18, 2015 6:30-8:30 PM This event is free and open to the public; donations will be accepted. Multnomah Friends Meeting House 4312 SE Stark On-street parking is limited; Meeting House is 4-5 blocks from bus lines #15 (Belmont @ 42nd), #20 (Burnside @ 44th) or #75 (Cesar Chavez/39th @ Stark). Or watch it live on ustream.tv/channel/occucakes (remove ads using Firefox and AdBlockPlus) Phyllis Bennis of the Institute for Policy Studies will conduct a video forum in Portland including a question and answer period Appearing via the internet from the east coast, the renowned analyst will focus on the US War on ISIS (/Islamic State), the debate over the Authorization for Use of Military Force, and the effects on the people of Iraq and Syria of the US-led war-- in which Iran is playing a key role. Bennis has been an advocate for diplomatic solutions in light of the ongoing state of war the US has been in at least since the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. Bennis will also give brief updates on Israel/Palestine and what's going on in Yemen. Coordinated by: Peace and Justice Works Iraq Affinity Group, funded in part by the Jan Bone Memorial Fund for public forums. cosponsored by Occupy Portland Elder Caucus, Americans United for Palestinian Human Rights (AUPHR), Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility, Jewish Voice for Peace-Portland, American Friends Service Committee, Veterans for Peace Chapter 72, Pacific Green Party, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom-Portland, and others. -

The Palestinians' Right of Return Point

Human Rights Brief Volume 8 | Issue 2 Article 2 2001 Point: The alesP tinians' Right of Return Hussein Ibish Ali Abunimah Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Ibish, Hussein, and Ali Abunimah. "Point: The aleP stinians' Right of Return." Human Rights Brief 8, no. 2 (2001): 4, 6-7. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Rights Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ibish and Abunimah: Point: The Palestinians' Right of Return point/ The Palestinians’ Right of Return The Controversy Over the by Hussein Ibish and Ali Abunimah* Right of Return alestinians are the largest and In 1947, after a wave of Jewish immigration, the United Nations most long-suffering refugee pop- voted to divide Palestine into Arab and Jewish sectors, with Jerusalem Pulation in the world. There are administered as an international enclave. Despite Arab opposition, more than 3.7 million Palestinians reg- istered as refugees by the United the Jews began to build their own state. On May 14, 1948, Israel Nations Relief and Work Agency declared its independence. Shortly thereafter, the War of Indepen- (UNRWA), the UN agency responsi- dence broke out when Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon refused to ble for them. -

Resource List for Palestine and Israel Film Series Feb

Resource List for Palestine and Israel Film Series Feb. 12 – March 19, 2018 Series hosted by Montpelier Senior Activity Center Films and Resources Selected by Vermonters for Justice in Palestine BOOKS Palestine Inside Out: An Everyday Occupation by Saree Makdisi, 2008. Powerfully written, well documented, and integrates the present with historical context, including the Nakba (known as the War of Independence in 1948). 298 pages. Ten Myths About Israel by Ilan Pappe; published in 2017 explores claims that are repeated over and over, among them that Palestine was an empty land at the time of the Balfour Declaration, , whether Palestinians voluntarily left their homeland in 1948, whether June 1967 was a war of “no choice,” and the myths surrounding the failures of the Camp David Accords. 167 pages. Sleeping on a Wire, Conversations with Palestinians by David Grossman, 1993. Written by Israel’s best known novelist, this is a book of insightful interviews that illuminate the contradictions of Zionism, behind which Grossman remains standing. 346 pages. The Battle for Justice in Palestine, Ali Abunimah, 2014. Well-written, accessible exploration of the fallacy of a neoliberal Palestine, Israel’s fight against BDS, and the potential benefit to Israelis and Palestinians of a one-state solution. 292 pages. The Myths of Liberal Zionism, Yitzhak Laor, 2009. A fascinating exploration of Israel’s writers and Zionism by an Israeli poet and dissident, illustrating the inherent conflict between Zionism and democracy. 160 pages. Goliath, Life and Loathing in Greater Israel, Max Blumenthal, 2013. Beginning with the national elections carried out in 2008-09, during Israel’s war on Gaza, this hard-hitting book by a prominent American-Jewish reporter examines the rise of far-right to power in Israel and its consequences for Jews and Palestinians, both in Israel and in the occupied territory. -

New Israeli Literature in Translation

NEW ISRAELI LITERATURE IN TRANSLATION To the Edge of Sorrow by Aharon Appelfeld Schocken Books, January 2019 See Also: The Man Who Never Stopped Sleeping (2017), Suddenly, Love (2014), Until the Dawn's Light (2011), Blooms of Darkness (2010), Laish (2009), All Whom I Have Loved (2007), The Story of a Life (2004) Judas by Amos Oz (translated by Nicholas de Lange) Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016 *paperback available* See Also: Dear Zealots: Letters from a Divided Land (11/2018), Between Friends (2013), Scenes from Village Life (2011), Rhyming Life & Death (2009), A Tale of Love and Darkness (2004), The Same Sea (2001) The Extra by A.B. Yehoshua (translated by Stuart Schoffman) Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016 *paperback available* See Also: The Retrospective (2013), Friendly Fire (2008), A Woman in Jerusalem (2006), The Liberated Bride (2003) A Horse Walks into a Bar by David Grossman (translated by Jessica Cohen) Knopf, 2017 *paperback available* See Also: Falling Out of Time (2014), To the End of the Land (2010), Lion’s Honey (2006), Her Body Knows (2005), Someone to Run With (2004) Two She-Bears by Meir Shalev (translated by Stuart Schoffman) Schocken Books, 2016 See Also: My Russian Grandmother and Her American Vacuum Cleaner (2011), A Pigeon and a Boy (2007), Four Meals (2002), The Loves of Judith (1999), The Blue Mountain (1991) Three Floors Up by Eshkol Nevo (translated by Sondra Silverston) Other Press, 2017 *in paperback* See Also: Homesick (2010) Waking Lions by Ayelet Gundar-Goshen (translated by Sondra Silverston) Little Brown, -

U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess They hate our freedoms--our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other (George W. Bush, Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People, September 20, 2001). These values of freedom are right and true for every person, in every society—and the duty of protecting these values against their enemies is the common calling of freedom-loving people across the globe and across the ages (National Security Strategy, September 2002 http://www. whitehouse. gov/nsc/nss. html). The historical connection between U.S. foreign policy and human rights has been strong on occasion. The War on Terror has not diminished but rather intensified that relationship if public statements from President Bush and his administration are to be believed. Some argue that just as in the Cold War, the American way of life as a free and liberal people is at stake. They argue that the enemy now is not communism but the disgruntled few who would seek to impose fundamentalist values on societies the world over and destroy those who do not conform. Proposed approaches to neutralizing the problem of terrorism vary. While most would agree that protecting human rights in the face of terror is of elevated importance, concern for human rights holds a peculiar place in this debate. It is ostensibly what the U.S. is trying to protect, yet it is arguably one of the first ideals compromised in the fight. -

A Better Place to Be Unhappy

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy A BETTER PLACE TO BE UNHAPPY Identity in Gary Shteyngart’s immigrant fiction Paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- Promotor: en Letterkunde: Nederlands – prof. dr. Philippe Codde August 2011 Engels” by Thomas Joos Acknowledgments In the acknowledgments of his latest novel, Gary Shteyngart says that “writing a book is real hard and lonely, let me tell you.” I don’t mean to steal his thunder, nor to underestimate the efforts required to write a novel comparable to his fiction, but writing a thesis on his books has been equally hard and lonely. Especially in the summertime. Let me tell you. Therefore, I would like to thank a number of people for helping me out or reminding me, once in a while, that I was still alive. First and foremost, my thanks go to my promotor prof. dr. Philippe Codde for his valuable feedback and for introducing me to Jewish American fiction in the first place. Also, I want to thank my parents, my brother Dieter and sister Eveline for supporting me, knowingly or unknowingly, from this world or another, at times when my motivation reached rock bottom. Finally, a big thank you to my closest friends, who made this 4-year trip at Ghent University definitely worthwile. Thomas Joos Ghent, August 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................. 1 PART ONE ............................................................................................................................... 7 I. GARY SHTEYNGART...................................................................................................... 7 II. THE IMMIGRANT EXPERIENCE IN JEWISH AMERICAN LITERATURE........... 11 1. Historical Overview ..................................................................................................... 11 2. 21 st -Century Jewish American Fiction........................................................................ -

And Pale Odia Palestinian Woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip

and Pale odia Palestinian woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip. Her home was demolished by Israeli military, (p.16) (Photo: Neal Cassidy) nunTHE JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE FOR PROGRESSIVE WOMEN VOL. XV SUMMER 1990 PUBLISHER/EDITOR IN CHIEF Merle Hoffman MANAGING EDITOR Beverly Lowy ASSOCIATE EDITOR Eleanor J. Bader ASSISTANT EDITOR Karen Aisenberg EDITOR AT LARGE Phyllis Chester CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Charlotte Bunch Vinie Burrows Naomi Feigelson Chase Irene Davall FEATURES Above: Goats on a porch at Toi Derricotte Mandala. All animals are treated with Roberta Kalechofsky BREAKING BARRIERS: affection and respect, even the skunks. Flo Kennedy WOMEN AND MINORITIES IN (p.10) (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Fred Pelka THE SCIENCES Cover: A single mother and her Helen M. Stummer ON THE ISSUES interviews children find permanency in a H.O.M.E.- ART DIRECTORS Paul E. Gray, President of MIT, and built home. (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Michael Dowdy Dean of Student Affairs, Shirley M. Julia Gran McBay, on sexism and racism in A SONG SO BRAVE — ADVERTISING AND SALES academia 7 PHOTO ESSAY DIRECTOR Text By Phyllis Chesler Carolyn Handel H.O.M.E. Photos By Joan Roth ONE WOMAN'S APPROACH Phyllis Chesler and an international ON THE ISSUES: A feminist, humanist TO SOCIETY'S PROBLEMS group of feminists present a Torah to publication dedicated to promoting By Helen M. Stummer political action through awareness and the women of Jerusalem 19 education; working toward a global Visual sociologist Helen M. Stummer political consciousness; fostering a spirit profiles a unique program to combat TO PEE OR NOT TO PEE of collective responsibility for positive homelessness, poverty and By Irene Davall social change; eradicating racism, disenfranchisement 10 A humorous recollection of the "pee- sexism, ageism, speciesism; and support- in" that forced Harvard to examine its ing the struggle of historically disenfran- FROM STONES TO sexism 20 chised groups to protect and defend STATEHOOD themselves. -

The Necessity of Including Hamas in Any Future Peace Process and the Viability of Doing So: an Argument for Reassessment and Engagement

THE NECESSITY OF INCLUDING HAMAS IN ANY FUTURE PEACE PROCESS AND THE VIABILITY OF DOING SO: AN ARGUMENT FOR REASSESSMENT AND ENGAGEMENT by Peter Worthington Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 2007 MAJOR PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES In the School of International Studies © Peter Worthington 2011 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2011 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Peter Worthington Degree: Master of Arts in International Studies Title of Thesis: The necessity of including Hamas in any future peace process and the viability of doing so: an argument for reassessment and engagement. Examining Committee: Chair: Dr John Harriss Professor of International Studies ______________________________________ Dr Tamir Moustafa Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Stephen Jarislowsky Chair School for International Studies ______________________________________ Dr. John Harriss Supervisor Professor of International Studies ______________________________________ Date Approved: April 26, 2011 ii Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

Helping to Shape the Policy Discourse on Palestine

Helping to Shape the Policy Discourse on Palestine Al-Shabaka in 2016 and into 2017 Al-Shabaka, The Palestinian Policy Network, is an independent, non- partisan, and non-profit organization whose mission is to educate and foster public debate on Palestinian human rights and self- determination within the framework of international law. Contents Letter from the Executive Director 1 1. Policy Insights and Options 2 2. Fielding the Policy Team in Strategic Locations 5 3. Expanding the Global Palestinian Think Tank 9 4. Outreach & Engagement 11 5. Financial Report and List of Donors 13 6. List of Publications 2010 - 2016 15 7. List of Al-Shabaka Analysts 22 Letter from the Executive Director With key anniversaries for Palestine and The network has grown by 30% since the Palestinians on the calendar in 2017 2015, with new policy members reinforcing and 2018, Israel’s aim to consolidate its existing areas of expertise as well as occupation went into overdrive. Over the providing coverage in additional geographic past year this has included a ramped- areas (see Section 3). Al-Shabaka’s reach up effort to erase the use of the term has also expanded through well-placed op- “occupation” from the public discourse eds in both the Arabic and English media, while multiplying settlement activity; the increased use of English and Arabic social drive to occupy key positions on United media, speaking engagements in many Nations committees while violating different locales, and translation of policy international law; and cracking down on free content into French and Italian, among speech and non-violent activism. -

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A. History w/ Departmental Honors ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE A SYSTEM OF DISCRIMINATION COVID-19 IMPACT Given that PalestiniansSTRACT are suffering from As is evident from headlines over the last year, Palestinians are faring much worse While many see the founding of Israel in 1948 as the beginning of discrimination against COVID-19 has amplified all of the existing issues of apartheid, which had put Palestinians the COVID-19 pandemic not only to a under the COVID-19 pandemic than Israelis. Many news sources focus mainly on the Palestinians, it actually extends back to early Zionist colonization in the 1920s. Today, in a place of being less able to fight a pandemic (or any major, global crisis) effectively. greater extent than Israelis, but explicitly present, discussing vaccine apartheid and the current conditions of West Bank, Gaza, discrimination against Palestinians continues at varying levels throughout West Bank, because of discriminatory systems put into and Palestinian communities inside Israel. However, few mainstream news sources Gaza, and Israel itself. Here I will provide some examples: Gaza Because of the electricity crisis and daily power outages in Gaza, medical place by Israel before the pandemic began, have examined how these conditions arose in the first place. My project shows how equipment, including respirators, cannot run effectively throughout the day, and the it is clear that Israel is responsible for taking the COVID-19 crisis in Palestine was exacerbated by existing structures of Pre-1948 When the infrastructure of what would eventually become Israel was first built, constant disruptions in power cause the machines to wear out much faster than they action to ameliorate the crisis. -

Disseminating Jewish Literatures

Disseminating Jewish Literatures Disseminating Jewish Literatures Knowledge, Research, Curricula Edited by Susanne Zepp, Ruth Fine, Natasha Gordinsky, Kader Konuk, Claudia Olk and Galili Shahar ISBN 978-3-11-061899-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-061900-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-061907-2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020908027 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020 Susanne Zepp, Ruth Fine, Natasha Gordinsky, Kader Konuk, Claudia Olk and Galili Shahar published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: FinnBrandt / E+ / Getty Images Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Introduction This volume is dedicated to the rich multilingualism and polyphonyofJewish literarywriting.Itoffers an interdisciplinary array of suggestions on issues of re- search and teachingrelated to further promotingthe integration of modern Jew- ish literary studies into the different philological disciplines. It collects the pro- ceedings of the Gentner Symposium fundedbythe Minerva Foundation, which was held at the Freie Universität Berlin from June 27 to 29,2018. During this three-daysymposium at the Max Planck Society’sHarnack House, more than fifty scholars from awide rangeofdisciplines in modern philologydiscussed the integration of Jewish literature into research and teaching. Among the partic- ipants werespecialists in American, Arabic, German, Hebrew,Hungarian, Ro- mance and LatinAmerican,Slavic, Turkish, and Yiddish literature as well as comparative literature.