Punjabi Language: a Study of Language Desertion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking at Punjabi Language Through a Researcher's Lens

Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 4, No. 1 (2012) Looking at the Punjabi Language through a Researcher’s Lens By Fakhira Riaz and Samina Amin Qadir It was a cold winter night and the sun had set hours ago, which triggered a desire to have a cup of tea at one of Islamabad’s misty tea jungle points. It was the time when I was at the stage of selecting a topic for my doctoral research. Being in the middle of thinking about what could add value to the literature highlighting a key phenomenon which was taking place in society, I heard a conversation between the owner of the tea shop and his son. Their words grabbed my attention because there was not just one language at play. I tried to make sense as to whether it was code mixing/code switching between two languages, or perhaps the dialect of a local language or the words of a dying language. But soon the realization that a predominantly low-income, perhaps uneducated, Punjabi speaker was not having a conversation with his son in the Punjabi language made an imprint on my mind. It was at that moment that I remembered last year’s birthday party for my best friend, Aleena. It was the middle of September and I was anxiously waiting to celebrate the birthday of Aleena. I, along with my friends, made several plans to make it a memorable day for her. Finally, the day arrived when we all gathered in the front lawn of her house which was beautifully decorated for the party. -

The Village, Which Was Selected for This Research, Is Located in Tehsil

Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 4, No. 1 (2012) Looking at the Punjabi Language through a Researcher’s Lens By Fakhira Riaz and Samina Amin Qadir It was a cold winter night and the sun had set hours ago, which triggered a desire to have a cup of tea at one of Islamabad’s misty tea jungle points. It was the time when I was at the stage of selecting a topic for my doctoral research. Being in the middle of thinking about what could add value to the literature highlighting a key phenomenon which was taking place in society, I heard a conversation between the owner of the tea shop and his son. Their words grabbed my attention because there was not just one language at play. I tried to make sense as to whether it was code mixing/code switching between two languages, or perhaps the dialect of a local language or the words of a dying language. But soon the realization that a predominantly low-income, perhaps uneducated, Punjabi speaker was not having a conversation with his son in the Punjabi language made an imprint on my mind. It was at that moment that I remembered last year’s birthday party for my best friend, Aleena. It was the middle of September and I was anxiously waiting to celebrate the birthday of Aleena. I, along with my friends, made several plans to make it a memorable day for her. Finally, the day arrived when we all gathered in the front lawn of her house which was beautifully decorated for the party. -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

Languages of Kohistan. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 1 LANGUAGES OF KOHISTAN Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Calvin R. Rensch Sandra J. Decker Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2002 ISBN 969-8023-11-9 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................viii Maps................................................................................................................. -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern -

Social Transformation of Pakistan Under Urdu Language

Social Transformations in Contemporary Society, 2021 (9) ISSN 2345-0126 (online) SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION OF PAKISTAN UNDER URDU LANGUAGE Dr. Sohaib Mukhtar Bahria University, Pakistan [email protected] Abstract Urdu is the national language of Pakistan under article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. Urdu language is the first brick upon which whole building of Pakistan is built. In pronunciation both Hindi in India and Urdu in Pakistan are same but in script Indian choose their religious writing style Sanskrit also called Devanagari as Muslims of Pakistan choose Arabic script for writing Urdu language. Urdu language is based on two nation theory which is the basis of the creation of Pakistan. There are two nations in Indian Sub-continent (i) Hindu, and (ii) Muslims therefore Muslims of Indian sub- continent chanted for separate Muslim Land Pakistan in Indian sub-continent thus struggled for achieving separate homeland Pakistan where Muslims can freely practice their religious duties which is not possible in a country where non-Muslims are in majority thus Urdu which is derived from Arabic, Persian, and Turkish declared the national language of Pakistan as official language is still English thus steps are required to be taken at Government level to make Urdu as official language of Pakistan. There are various local languages of Pakistan mainly: Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, Balochi, Kashmiri, Balti and it is fundamental right of all citizens of Pakistan under article 28 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973 to protect, preserve, and promote their local languages and local culture but the national language of Pakistan is Urdu according to article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. -

Study of Distinguishing Features of Pakistani Ameer Ali At

Study of Distinguishing Features of Pakistani Ameer Ali at. al STUDY OF DISTINGUISHING FEATURES OF PAKISTANI STANDARD ENGLISH Ameer Ali1, Abdul Wahid Samoon2, Mansoor Ali3 1,2Applied Linguistics at the University of Sindh, Jamshoro, 3English at College Education and Literacy Department Sindh. Pakistan. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT The current research has adopted a qualitative approach to investigate the linguistic differences of Pakistani Standard English in contrast to British Standard English. We studied morphological, lexical, and hybrid characteristics of Pakistani Standard English. Besides, we investigated the linguistic features to prove the fact that cultural context determines the use of a language. Moreover, the findings of this research also support the fact that a language keeps evolving in different contexts leading to the development of different varieties of the language. However, the researchers have studied comparatively many varieties of Englishes, but this research investigates the distinguishing features of Pakistani Standard English employing secondary data from Dawn e-newspaper. Additionally, the researchers have also qualitatively codified the data into broader themes. The findings of this research will help readers in understanding the role of a cultural context in developing a new variety of a language. Consequently, they will be able to carry out further research in the field of World Englishes. Hence, this research is a systematic investigation of Pakistani Standard English and its differentiating features. Keywords: Englishes, varieties, Pakistani Standard English, different contexts. ABSTRAK Penelitian ini telah mengadopsi pendekatan kualitatif untuk menyelidiki perbedaan linguistik Bahasa Inggris Standar Pakistan berbeda dengan Bahasa Inggris Standar Inggris. Para peneliti mempelajari karakteristik morfologi, leksikal, dan hibrida dari Bahasa Inggris Standar Pakistan. -

English Language in Pakistan: Expansion and Resulting Implications

Journal of Education & Social Sciences Vol. 5(1): 52-67, 2017 DOI: 10.20547/jess0421705104 English Language in Pakistan: Expansion and Resulting Implications Syeda Bushra Zaidi ∗ Sajida Zaki y Abstract: From sociolinguistic or anthropological perspective, Pakistan is classified as a multilingual context with most people speaking one native or regional language alongside Urdu which is the national language. With respect to English, Pakistan is a second language context which implies that the language is institutionalized and enjoying the privileged status of being the official language. This thematic paper is an attempt to review the arrival and augmentation of English language in Pakistan both before and after its creation. The chronological description is carried out in order to identify the consequences of this spread and to link them with possible future developments and implications. Some key themes covered in the paper include a brief historical overview of English language from how it was introduced to the manner in which it has developed over the years especially in relation to various language and educational policies. Based on the critical review of the literature presented in the paper there seems to be no threat to English in Pakistan a prediction true for the language globally as well. The status of English, as it globally elevates, will continue spreading and prospering in Pakistan as well enriching the Pakistani English variety that has already born and is being studied and codified. However, this process may take long due to the instability of governing policies and law-makers. A serious concern for researchers and people in general, however, will continue being the endangered and indigenous varieties that may continue being under considerable pressure from the prestigious varieties. -

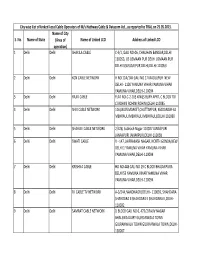

City Wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/S Hathway Cable & Datacom Ltd., As Reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015

City wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/s Hathway Cable & Datacom Ltd., as reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015. Name of City S. No. Name of State (Area of Name of Linked LCO Address of Linked LCO operation) 1 Delhi Delhi SHAKILA CABLE C‐9/1, GALI NO‐06, CHAUHAN BANGAR,DELHI 110053, US USMAAN PUR DELHI USMAAN PUR DELHI USMAAN PUR DELHI,DELHI‐110053 2 Delhi Delhi KCN CABLE NETWORK H NO 12A/14K GALI NO 17 MAOUJPUR NEW DELHI ‐ 1100 YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR,DELHI‐110094 3 Delhi Delhi RAJIV CABLE FLAT NO‐C‐2‐103 KINGS BURY APRT, C BLOCK TDI CI ROHINI ROHINI ROHINI,DELHI‐110085 4 Delhi Delhi SHIV CABLE NETWORK 116,MAIN MARKET,CHATTARPUR, MADANGIR‐62 MEHRAULI MEHRAULI MEHRAULI,DELHI‐110030 5 Delhi Delhi SHAHJEE CABLE NETWORK 2/428, Subhash Nagar‐110027 JANAKPURI JANAKPURI JANAKPURI,DELHI‐110058 6 Delhi Delhi SWATI CABLE V ‐ 147, JAIPRAKASH NAGAR, NORTH GONDA,NEW DELHI 1 YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR,DELHI‐110094 7 Delhi Delhi KRISHNA CABLE HO NO 448 GALI NO 19 C BLOCK BHAJANPURA DELHI 53 YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR YAMUNA VIHAR,DELHI‐110094 8 Delhi Delhi R I CABLE TV NETWORK A‐3/244,NANDNAGRI,DELHI ‐ 110093, SHAHDARA SHAHDARA II SHAHDARA II SHAHDARA II,DELHI‐ 110032 9 Delhi Delhi SAMRAT CABLE NETWORK D BLOCK GALI NO 6, 473/2 RAJIV NAGAR BHALSWA DAIRY GUJRANWALA TOWN GUJRANWALA TOWN GUJRANWALA TOWN,DELHI‐ 110007 City wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/s Hathway Cable & Datacom Ltd., as reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015. -

Download (1MB)

Abrar, Muhammad (2012) Enforcement and regulation in relation to TV broadcasting in Pakistan. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3771/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Enforcement and Regulation in Relation to TV Broadcasting in Pakistan Muhammad Abrar Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow November 2012 Abstract Abstract In 2002, private broadcasters started their own TV transmissions after the creation of the Pakistan Electronic Media Authority. This thesis seeks to identify the challenges to the Pakistan public and private electronic media sectors in terms of enforcement. Despite its importance and growth, there is a lack of research on the enforcement and regulatory supervision of the electronic media sector in Pakistan. This study examines the sector and identifies the action required to improve the current situation. To this end, it focuses on five aspects: (i) Institutional arrangements: institutions play a key role in regulating the system properly. (ii) Legislative and regulatory arrangements: legislation enables the electronic media system to run smoothly. -

Media Coverage for Development of Agriculture Sector: an Analytical Study of Television Channels in Pakistan

Media coverage for development of agricultural sector: An analytical study 555 MEDIA COVERAGE FOR DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE SECTOR: AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF TELEVISION CHANNELS IN PAKISTAN Anjum Zia* and Ayesha Khan** ABSTRACT Agriculture sector is considered to be the bedrock of Pakistan’s economy as it plays an important role, directly as well as indirectly, in generating economic and industrial growth. In-spite of such a great significance, the speed of agricultural development in Pakistan is very low. Agricultural production can be increased considerably if available modern production technologies are adopted by the farming community. Media is considered to be one of the best tools to create awareness about the effectiveness and application of new technologies. So the present study was conducted in the Department of Mass Communication, Lahore College for Women, Lahore, Pakistan during the year 2011 to determine extent of television coverage for development of agriculture sector in Pakistan for the period 2006-2010. Data were collected from media practitioners of private and public television channels by applying intensive interview technique. The study concludes that there is only one dedicated television channel (Sohni Dharti) for agriculture sector out of 82 channels. Indeed, a single agricultural channel is inadequate for an agrarian country having 67 percent of total population living in rural areas and 44.7 percent of them connected to farming. The data further indicate that no other television channel was giving due coverage to third largest sector of the economy. However, these television channels were found occasionally accommodating agricultural news items/news packages in their current affair programmes and news bulletins. -

Overview: N.W.F.P. / F.A.T.A

Overview: N.W.F.P. / F.A.T.A. ± TAJIKISTAN Zhuil ! Lasht ! Moghlang Nekhcherdim ! ! Mastuj Morich ! Nichagh Sub-division ! Muligram ! Druh ! Rayan ! Brep ! Zundrangram ! Garam Chashma Chapalli ! Bandok ! ! Drasan ! Arkari ! Sanoghar Nawasin ! Ghari ! CHITRAL Lon ! Afsik Besti ! ! Nichagh ! Harchin Dung ! Gushten Beshgram ! ! Laspur ! Imirdin ! Mogh Maroi ! ! Darband ! Koghozi ! Serki ! Singur ! AFGHANISTAN Chitral Sub-division Goki Shahi ! Nekratok ! JAMMU AND KASHMIR Kuru Atchiku Paspat ! ! ! Brumboret ! Kalam Tar ! Gabrial SWAT ! Drosh ! Banda-i- Kalam Sazin ! ! Dong Utrot ! Lamutai ! Mirkhani ! Halil ! ! Harianai ! Babuzai Dammer ! Nissar Sur ! Biar Banda Dassu Sub-division ! ! Biaso Dir Sub-division ! Gujar Banda Arandu ! Chodgram KOHISTAN Chochun ! ! ! Ayagai ! Bahrain Dadabund UPPER DIR Banda ! Bahrain ! ! Ushiri Pattan Sub-division ! Chachargah Chutiatan Daber ! ! ! Baiaul Patan Bandai ! ! Kwana ! Matta Sebujni Fazildin-Ki-Basti Gidar ! Nachkara ! ! Bara Khandak Drush Palas Sub-division Shenkhor ! Khel ! Saral Matta ! Alpuri Tehsil Baihk Aligram Domela ! Wari Sub-division ! Rambakai ! Khararai ! Barwa Domel ! ! Burawai Jandool Dardial Khwazakhela ! ! Khal Alamganj Shang BAJAUR Sub-division ! ! Bar ! Kaga Kotkai ! ! Pokal Pashat Kabal ! ! Dadai Mian ! SHANGLA Allai Tehsil ! Kili LOWER DIR Galoch Charbagh Bisham Mamund Salarzai ! Te h si l Tehsil Khongi Aspanr Chakisar Tehsil! Bala Kot Tehsil ! ! Mongora Alagram Dandai BATAGRAM !Khalozai Utman ! ! Tehsil Lari Anangurai Ajoo ! Nawagai Khel ! ! Jatkol Panjnadi Khar Bajaur Babuzai !