Eastern Abenaki Autonomy and French Frustrations, 1745-1760

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MOG Biography

Dictionary of Canadian Biography MOG (Heracouansit, Warracansit, Warracunsit, Warrawcuset), a noted warrior, subchief, and orator of the Norridgewock (Caniba) division of the Abenakis, son of Mog, an Abenaki chief killed in 1677; b. c. 1663; killed 12 Aug. 1724 (O.S.) at Norridgewock (Narantsouak; now Old Point in south Madison, Me). In the La Chasse* census of 1708, Mog is listed under the name Heracouansit (in Abenaki, welákwansit, “one with small handsome heels”). During King William’s and Queen Anne’s Wars Mog took part in the numerous raids on English settlements by Abenakis and carried captives and scalps to Quebec. Following the peace of Utrecht in April 1713, Mog, Bomoseen, Moxus, Taxous, and other chiefs concluded a peace with New England at Portsmouth, N.H., on 11– 13 July. The Abenakis pledged allegiance to Anne, though “it is safe to say that they did not know what the words meant” (Parkman). They also admitted the right of the English to land occupied before the war. The English, on their side, promised that the Indians could settle any individual grievances with them in English courts. Mog and the others then sailed with six New England commissioners to Casco Bay, where the treaty and terms of submission were read to 30 chiefs, in the presence of 400 other Abenakis, on 18 July. “Young Mogg” was described as “a man about 50 years, a likely Magestick lookt Man who spake all was Said.” The Abenakis expressed surprise when told that the French had surrendered all the Abenaki lands to the English: “wee wonder how they would give it away without asking us, God having at first placed us there and They having nothing to do to give it away.” Father Sébastien RALE, the Jesuit missionary at Norridgewock, reported a month later that he had convinced the Indians the English were deceiving them with an ambiguous phrase, for England and France still disagreed about the limits of “Acadia.” Apparently the Indians remained disturbed, however, when the English offered to show them the official text of the European treaty in the presence of their missionaries. -

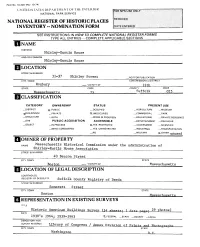

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ShirleyrEustis Rouse AND/OR COMMON Shirley'-Eustis House LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 31^37 Shirley Street -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Roxbury _ VICINITY OF 12th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 9^ Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -^BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY x-OTHER unused OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Massachusetts Historical Commission under the administration of ShirleyrEustis Eouse Association_________________________ STREETS NUMBER 4Q Beacon Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Mas s achtis e t t s REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (14 sheets. 1 29 photos) DATE 1930 f-s 1964. 1939^1963 FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress / Annex Division of Prints and CITY. TOWN STATE Washington n.r DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED —UNALTERED __ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS ^ALTERED DATE. -FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The house, constructed from 1741 to 1756 for Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts became somewhat of a colonial showplace with its imposing facades and elaborate interior designs. -

Re-Membering Norridgewock Stories and Politics of a Place Multiple

RE-MEMBERING NORRIDGEWOCK STORIES AND POLITICS OF A PLACE MULTIPLE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ashley Elizabeth Smith December 2017 © 2017 Ashley Elizabeth Smith RE-MEMBERING NORRIDGEWOCK STORIES AND POLITICS OF A PLACE MULTIPLE Ashley Elizabeth Smith, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 This dissertation is an ethnography of place-making at Norridgewock, the site of a famous Wabanaki village in western Maine that was destroyed by a British militia in 1724. I examine how this site is variously enacted as a place of Wabanaki survivance and erasure and ask, how is it that a particular place with a particular history can be mobilized in different and even contradictory ways? I apply Annemarie Mol’s (2002) analytic concept of the body multiple to place to examine how utilize practices of storytelling, remembering, gathering, producing knowledge, and negotiating relationships to variously enact Norridgewock as a place multiple. I consider the multiple, overlapping, coexistent, and contradictory enactments of place and engagements with knowledge that shape place-worlds in settler colonial nation-states. Rather than taking these different enactments of place to be different perspectives on or versions of place, I examine how these enactments are embedded in and shaped by hierarchies of power and politics that produce enactments of place that are at times parallel and at times contradictory. Place-making is especially political in the context of settler colonialism, where indigenous places, histories, and peoples are erased in order to be replaced (Wolfe 2006; O’Brien 2010). -

The Phoenix of Colonial War: Race, the Laws of War, and the ‘Horror on the Rhine’

The Phoenix of Colonial War: Race, the Laws of War, and the ‘Horror on the Rhine’ Rotem Giladi+* Abstract The paper explores the demise of the ‘colonial war’ category through the employment of French colonial troops, under the 1918 armistice, to occupy the German Rhineland. It traces the prevalence of—and the anxieties underpinning— antebellum doctrine on using ‘Barbarous Forces’ in ‘European’ war. It then records the silence of postbellum scholars on the ‘horror on the Rhine’—orchestrated allegations of rape framed in racialised terms of humanity and the requirements of the law of civilised warfare. Among possible explanations for this silence, the paper follows recent literature that considers this scandal as the embodiment of crises in masculinity, white domination, and European civilisation. These crises, like the scandal itself, expressed antebellum jurisprudential anxieties about the capacity—and implications—of black soldiers being ‘drilled white’. They also deprived postbellum lawyers of the vocabulary necessary to address what they signified: breakdown of the laws of war; evident, self-inflicted European barbarity; and the collapse of international law itself, embodied by the Versailles Diktat treating Germany—as Smuts warned, ‘as we would not treat a kaffir nation’—a colonial ‘object’, as Schmitt lamented. Last, the paper traces the resurgence of ‘colonial war’. It reveals how, at the moment of collapse, in the very instrument signifying it, the category found a new life. The Covenant’s Art.22(5) reasserted control over the colonial object, thus furnishing international lawyers with new vocabulary to address the employment of colonial troops— yet, now, as part of the ‘law of peace’. -

2012 Annual Report for the Fiscal Year 2010-2011 (Old Trail Along the Kennebec Known As ‘The Pines’) “In Every Walk with Nature One Receives Far More Than He Seeks

TOWN OF MADISON 2012 ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR 2010-2011 (OLD TRAIL ALONG THE KENNEBEC KNOWN AS ‘THE PINES’) “IN EVERY WALK WITH NATURE ONE RECEIVES FAR MORE THAN HE SEEKS. - JOHN MUIR” ABOUT THE COVER... This year’s cover story focuses on ‘Preserving Madison’s History’. We will discuss what we’ve done to preserve The Pines, Weston Homestead, and our two Historical Societies. THE PINES A recreational trail grant application was made to the Maine Department of Conservation on November 3, 2009 for trail improvements at the Old Point Mission Site now known as “The Pines”. The grant, in the amount of $25,600, was approved in May 2010. The history of The Pines, then known as ‘Norridgewock’ is both fascinating and tragic. Extensively documented and widely known, the Abenaki Village and associated Jesuit Mission at Old Point played a significant role in the Indian and French struggle to maintain control in the region during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The Old Point Mission was originally established in the mid-1690’s when Jesuit missionary Sebastian Rasle travelled from Quebec to Norridgewock. Father Rasle lived at Norridgewock for nearly 30 years during a tumultuous time of warfare and frontier conflict. Raids against British colonizers encroaching on Indian lands finally led to the outbreak of a new conflict from 1722 until 1727, known as Dummer’s War. Norridgewock was destroyed when a force of more than 150 New England troops killed Rasle and as many as 60 townsfolk on August 23, 1724. Interest in the Norridgewock Mission extends back to the early 1800s when Father Benedict Fenwick of Boston instigated purchase of a portion of Old Point in 1833 and sponsored construction of a monument honoring Rasle at the locale. -

·: ·· · ..."R<· ::- ·

.. 326' KEYES.-KI_DDER.-Knm.!LL.-KDIYI~GH.!M.-KING. tei(pounds for thrlsetting of an house, and to be paid in 'by the fiTst f ~· next, and that John Kettle shall d-..en in it so Ion,,. as the towne "th~ ktl [Town r~~ord.] Mr. T. B. \Yyman ~P~..?ses him to be the John Ke:t~e cC . ', ~ cester, 16031 then aged 32. and \Tao d m ~alem. Oct. 12, 1685 leavinrr wife ~... · ·I BETH, and 6 chit. His ln~enrory included 300 'acres of land ~ear N:Shi:;a. ~~ MARY KED.lLL, m., Jan. 11, Jii:H-3, THO'.\i.G \VHIT:-tEY. (32.) . •• ' . :· BE'l'HIA KEDALL1 m ., Nov. 3; 1660, THEOPHILUS PHILIPS. (24.] .! ~ .. " ES Ke s Keies .-ROBERT KEYES, of Wat:, by wife S~ 1. SARAH, . ay. , . •. Rr..,,i:ccA, b. ~far. 17, 1637-8. 3. Pm:ec. b,: - 17, ~639. ~- MA_:RY, b. 16-1 1, d.. 16-1-2~ 5. Eux;, b. May ~o, 1643, settled.ht m., ::Sept. 11, 166:J, SAlUE. Bus:>FCHD, and had several ch1l. 6. MARY, b.iia . bury1 June 16, 16451 where :he ::clier (Robert) d. July 16, 1647. He \vas p . the father of Solomon, of~ ~wooer: who m., Oct. 2, 16531 Frances Grant, and · have been the father of J 0~'1: oi Springfield, in 1669. [See Ward1 339--V'f · · Coffin, 307 .] · · .. • I . - l KIDDER.-JOH~ ~IDDES,, of Waltham, m., Nov. 2; 1775, EL.IZ.U · TOWNSEND, and had, ELIZ..8CTE: bap. Oct. 13: 1776. [Townsend1 10.J JoHN KIDDER1 of Char e5towe, m., Dec. -

People in Nature: Environmental History of the Kennebec River, Maine Daniel J

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 2003 People in Nature: Environmental History of the Kennebec River, Maine Daniel J. Michor Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Michor, Daniel J., "People in Nature: Environmental History of the Kennebec River, Maine" (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 188. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/188 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. PEOPLE IN NATURE: ENVlRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE KENNEBEC RIVER, MAINE BY Daniel J. Michor B.A. University of Wisconsin, 2000 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2003 Advisory Committee: Richard Judd, Professor of History, Advisor Howard Segal, Professor of History Stephen Hornsby, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Huryn, Associate Professor of Aquatic Entomology PEOPLE IN NATURE: ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE KENNEBEC RIVER, MAINE By Daniel J. Michor Thesis Advisor: Dr. Richard Judd An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in History) May, 2003 The quality of a river affects the tributaries, lakes, and estuary it feeds; it affects the wildlife and vegetation that depend on the river for energy, nutrients, and habitat, and also affects the human community in the form of use, access, pride, and sustainability. -

Maine Guide to Camp & Cottage Rentals 1992

MAINE Guide to Camp & Cottage Rentals 1992 An Official Publication of the Maine Publicity Bureau, Inc. MAINE. The Way Life Should Be. Maine Guide to Camp & Cottage Rentals 1992 Publisher/Editor Sherry L. Verrill Production Assistant Diane M. Hopkins TABLE OF CONTENTS South Coast 3-7 Western Lakes and Mountains 8-15 Kennebec Valley/Moose River Valley 16-20 Mid Coast 21-32 Acadia 33-44 Sunrise County 45-50 Katahdin/Moosehead 51-56 Aroostook County 57 Index to Advertisers 58-61 Maine Visitor Information Centers 62 A PUBLICATION OF THE MAINE PUBLICITY BUREAU, INC. P.O. Box 2300, Hallowell, Maine 04347 (207) 582-9300 • • » a The Maine Publicity Bureau, Inc Mail: P.O. Box 2300 209 Maine Avenue Hallowell, Maine 04347-2300 Farmingdale, Maine 04344 FAX 207-582-9308 Tel. 207-582-9300 Dear Friend: Renting a camp or cottage is a delightful way to experience the splendors of Maine. As you browse through these pages, imagine yourself relaxing in your own cozy spot after a day full of Maine enchantment. This guide is a reliable source of camp and cottage rentals. Owners and agents who list properties here are expected to obey The Golden Rule by dealing with others as they would want others to deal with them. We track any complaints about an owner or agent who fails to live up to standards of honesty and fairness. If a pattern develops concerning a listing, it is removed. Tens of thousands of people have used this guide to obtain just the spot they wanted. You, too, can use the guide confidently. -

The Uncommon Enemy: First Nations and Empires in King William's War

The Uncommon Enemy: First Nations and Empires in King William's War By Steven Schwinghamer A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History May 2007, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright Steven Schwinghamer, 2007 Dr Greg Marquis External Examiner Dr Michael Vance Reader Dr John Reid Supervisor Date: 4th May 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-30278-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-30278-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Thomas S. Kidd, “'The Devil and Father Rallee': the Narration of Father Rale's War in Provincal Massachusetts” Histori

Thomas S. Kidd, “’The Devil and Father Rallee’: The Narration of Father Rale’s War in Provincal Massachusetts” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 30, No. 2 (Summer 2002). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/mhj/.” Editor, Historical Journal of Massachusetts c/o Westfield State University 577 Western Ave. Westfield MA 01086 “The Devil and Father Rallee”: The Narration of Father Rale’s War in Provincial Massachusetts By Thomas S. Kidd Cotton Mather’s calendar had just rolled over to January 1, 1723, and with the turn he wrote his friend Robert Wodrow of Scotland concerning frightening though unsurprising news: “The Indians of the East, under the Fascinations of a French Priest, and Instigations of our French Neighbours, have begun a New War upon us…”1 Though they had enjoyed a respite from actual war since the Peace of Utrecht postponed hostilities between the French and British in 1713, New Englanders always knew that it was only a matter of time before the aggressive interests, uncertain borders, and conflicting visions of the religious contest between them and the French Canadians would lead to more bloodshed. -

The Circulating Medium of Exchange in Colonial Pennsylvania, 1729-1775

The Circulating Medium of Exchange in Colonial Pennsylvania, 1729-1775: * New Estimates of Monetary Composition and Economic Growth Farley Grubb Economics Dept. Univ. of Delaware Newark, DE 19716 USA July 3, 2001 Preliminary Draft Comments Welcome * The author is Professor of Economics, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716 USA. E-mail: [email protected]. The author thanks Peter Coclanis, Joseph Mason, Ronald Michener, and Richard Sylla for helpful suggestions. Anne Pfaelzer de Ortiz provided research and editorial assistance. The Circulating Medium of Exchange in Colonial Pennsylvania, 1729-1775: * New Estimates of Monetary Composition and Economic Growth Market transaction data are used to estimate the composition and quantity of specie in circulation. This estimate is used to provide the first comprehensive measure of the colony's money supply. This estimate, along with data on population and prices, is used to measure the growth in output using the quantity theory of money. Output growth is found to depend on periodization and the extent to which rising commercialization increased the velocity of circulation. Specie was scarce but becoming less so as the Revolution approached, and specie and paper currency were both substitutes and complements depending on the period of analysis. Nobody knows the amount of specie in circulation in colonial America. The absence of this one piece of information has left unanswered a number of important questions about how colonial economies worked. One such question is whether specie was scarce in colonial America. Some writers believe it was scarce (Brock 1975, pp. 86, 267, 386; Bouton 1996; Lester 1938; Walton and Shepard 1979, pp. -

The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China

Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China Ringmar, Erik 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Ringmar, E. (2013). Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China. Palgrave Macmillan. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Part I Introduction 99781137268914_02_ch01.indd781137268914_02_ch01.indd 1 77/16/2013/16/2013 1:06:311:06:31 PPMM 99781137268914_02_ch01.indd781137268914_02_ch01.indd 2 77/16/2013/16/2013 1:06:321:06:32 PPMM Chapter 1 Liberals and Barbarians Yuanmingyuan was the palace of the emperor of China, but that is a hope lessly deficient description since it was not just a palace but instead a large com- pound filled with hundreds of different buildings, including pavilions, galleries, temples, pagodas, libraries, audience halls, and so on.