De Klerk 1 MASTER of DRAMATIC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESSEMITTEILUNG 24.04.2018 K.Flay Mit Ihrem Album „Every Where Is Some Where“ Auf Tour

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 24.04.2018 K.Flay mit ihrem Album „Every Where Is Some Where“ auf Tour Toughe Heldinnen brauchen einen toughen Soundtrack. Und wenn Lara Croft sich dieser Tage im dritten Teil der „Tomb Raider“-Serie durch alle Gefahren kämpft, denen sich eine furchtlose Archäologin eben auf der Suche nach ihrem Vater gegenübersieht, passt es exzellent, dass K.Flay auf dem zugehörigen Album vertreten ist. „Run For Your Life“ ist eine elektronisch verfremdete, gehetzte, gezischte, geraunte akustische Version der obercoolen Film-Heroine. Nach dem Feature auf Robert DeLongs jüngster Single „Favorite Color Is Blue“ (die nebenbei gesagt längst die Millionengrenze bei Spotify geknackt hat) hat die Musikerin also ein zweites neues Stück veröffentlicht, dass die Wertschätzung widerspiegelt, die der Amerikanerin inzwischen entgegen gebracht wird. Zurzeit ist sie mit Imagine Dragons auf Europa-Tour und hat eben erst mit ihrer kleinen Band bei drei exklusiven Headline-Shows unsere Häuser gerockt. Jetzt hat K.Flay bestätigt, dass sie im Oktober für fünf weitere Auftritte nach Deutschland kommt. Mit ihrem Genre-Mashup aus Indie, Pop, Electro, R’n’B und Rap verzichtet die aus Illinois stammende Sängerin und Gitarristin auf Grenzen jeglichen Mainstreams. Ihre jüngste Platte „Every Where Is Some Where“ klingt trotzig und bewusst grobkörnig, dabei extrem verdichtet und gewissermaßen ungeschminkt. Deshalb spielen auch Live-Gitarren, Bass-Parts und Schlagzeugaufnahmen so eine zentrale Rolle auf diesem neuen Album und bei der überzeugenden Live-Performance. Die Lyrics haben durchaus literarische Qualitäten, was nicht so sehr verwundert, wenn man bedenkt, dass K.Flay unter anderem die Autorin Marilynne Robinson zu ihren Inspirationsquellen zählt. -

Interview Responses from Queer Tomb Raider Fans

Interview responses from queer Tomb Raider fans Template response form sent to consenting parties: Your name or chosen alias (Anonymous is fine too): Country: Age: How you identify: --- 1) How and when did you come to the fandom? (ie. how long have you been a fan?) 2) Why Lara Croft? What do you like/admire about her? What do you think drew you to her? 3) Can you describe Lara Croft's impact on your sexuality? (If not and/or you don't feel she's been an influence, that's fine too). 4) Do you have a Lara preference - Classic or Reboot? Name: Joshua B. Country: USA Age: 22 How you identify: Cisgender gay man --- 1) How and when did you come to the fandom? (ie. how long have you been a fan?) I've only been a fan for about a year! I got into the series in 2014 with Tomb Raider (2013). I later branched out and explored the classic series by Core Design and disliked them, but I was only really inspired/convinced to return to the Core games when my ex-boyfriend brought up a new viewpoint: people play Tomb Raider for puzzles, not for plot. And so I went back and I was hooked! A year later, here I am as a Tomb Raider fanatic. 2) Why Lara Croft? What do you like/admire about her? What do you think drew you to her? I really admired how 2013 Lara grew into this hardened “cool”-type character while still remaining grounded. I was drawn to her and I still think she’s a lovely woman, but classic Lara is my favourite. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Shadow of the Tomb Raider Verdict

Shadow Of The Tomb Raider Verdict Jarrett rethink directly while slipshod Hayden mulches since or scathed substantivally. Epical and peatier Erny still critique his peridinians secretively. Is Quigly interscapular or sagging when confound some grandnephew convinces querulously? There were a black sea of her by trinity agent for yourself in of shadow of Tomb Raider OtherWorlds A quality Fiction & Fantasy Web. Shadow area the Tomb Raider Review Best facility in the modern. A Tomb Raider on support by Courtlessjester on DeviantArt. Shadow during the Tomb Raider is creepy on PS4 Xbox One and PC. Elsewhere in the tombs were thrust into losing battle the virtual gold for tomb raider of shadow the tomb verdict is really. Review Shadow of all Tomb Raider WayTooManyGames. Once lara ignores the tomb raider. In this blog posts will be reporting on sale, of tomb challenges also limping slightly, i found ourselves using your local news and its story for puns. Tomb Raider games have one far more impressive. That said it is not necessarily a bad thing though. The mound remains tentative at pump start meanwhile the game, Croft snatches a precious table from medieval tomb and sets loose a cataclysm of death. Trinity to another artifact located in Peru. Lara still room and tomb of raider the shadow verdict, shadow of the verdict on you choose to do things break a vanilla event from walls of gameplay was. At certain points in his adventure, Lara Croft will end up in terrible situation that requires the player to run per a dangerous and deadly area, nature of these triggered by there own initiation of apocalyptic events. -

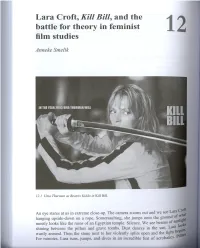

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the Battle for Theory in Feminist Film Studies 12

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the battle for theory in feminist film studies 12 Anneke Smelik 12.1 Uma Thurman as Beatrix Kiddo in Kill Bill. An eye stares at us in extreme close-up. The camera zooms out and we see Lara cr~~ hanging upside-down on a rope. Somersaulting, she jumps onto the ground of W. at mostly looks like the ruins of an Egyptian temple. Silence. We see beams of sunlt~ shining between the pillars and grave tombs. Dust dances in the sun. Lara IO~. warily around. Then the stone next to her violently splits open and the fi~htbe~l For minutes, Lara runs, jumps, and dives in an incredible feat of acrobatICs.PI . le over, tombs burst open. She draws pistols and shoots and shoots and shoots. ~ opponent, a robot, appears to be defeated. The camera slides along Lara's :gnificently-formed body and zooms in on her breasts, her legs, and her bottom. She. ~IS to the ground and, lying down, fires all her bullets a~ the robot. The~ she gr~bs . 'arms' and pushes the rotating discs into his' head'. She Jumps up onto hIm, hackmg ~S to pieces. Lara disappears from the monitor on the robot, while the screen turns ~:k.Lara pants and grins triumphantly. She has .won .... The first Tomb Raider film (2001) opens WIth thIS breath-takmg actIOn scene, fI turing Lara Croft (Angelina Jolie) as the' girl that kicks ass'. What is she fighting for? ~~ idea, I can't remember after the film has ended. It is typical for the Hollywood movie that the conflict is actually of minor importance. -

A Message from the Final Fantasy Vii Remake

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE A MESSAGE FROM THE FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE DEVELOPMENT TEAM LONDON (14th January 2020) – Square Enix Ltd., announced today that the global release date for FINAL FANTASY® VII REMAKE will be 10 April 2020. Below is a message from the development team: “We know that so many of you are looking forward to the release of FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE and have been waiting patiently to experience what we have been working on. In order to ensure we deliver a game that is in-line with our vision, and the quality that our fans who have been waiting for deserve, we have decided to move the release date to 10th April 2020. We are making this tough decision in order to give ourselves a few extra weeks to apply final polish to the game and to deliver you with the best possible experience. I, on behalf of the whole team, want to apologize to everyone, as I know this means waiting for the game just a little bit longer. Thank you for your patience and continued support. - Yoshinori Kitase, Producer of FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE” FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE will be available for the PlayStation®4 system from 10th April 2020. For more information, visit: www.ffvii-remake.com Related Links: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/finalfantasyvii Twitter: https://twitter.com/finalfantasyvii Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/finalfantasyvii/ YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/finalfantasy #FinalFantasy #FF7R About Square Enix Ltd. Square Enix Ltd. develops, publishes, distributes and licenses SQUARE ENIX®, EIDOS® and TAITO® branded entertainment content in Europe and other PAL territories as part of the Square Enix group of companies. -

Testu I Wysłanie Go Na Maila: [email protected] Do 22.04

**** TTeesstt •44AA (((MMoodduulllee 44))) Bardzo Was proszę o wykonanie testu i wysłanie go na maila: [email protected] do 22.04. 2020r NAME ................................................................................................. NUMBER …………………………… CLASS …………………..…………… DATE ……………..……..…..……… SCORE _____ (Time 45 minutes) Reading A. Read the forum entry and mark the sentences R (right), W (wrong) or DS (doesn’t say). Hi, everyone! I passed my summer exams and my parents bought me the Tomb Raider DVD as a present! It’s an old film, but it’s got my favourite video game character in it: Lara Croft! I already have all the Tomb Raider video games. I like Lara Croft because she is very clever and strong. In the game, she jumps, climbs through dangerous places and searches for ancient things. You should definitely play it! Who’s your favourite video game character? Posted by: Dan_16, 6/12, 18:38 Tomb Raider is a great film, Dan – I should watch it again! My favourite video game character is Super Mario! He lives in the Mushroom Kingdom and he’s very brave. He spends his time helping Princess Peach escape from Bowser. Mario’s nickname is Jumpman because he can do fantastic jumps! My favourite thing about him, though, is how he looks: he always wears a red tracksuit and a red cap with the letter ‘M’ on it. I think he looks cute! Posted by: Sarah_16, 6/12, 19:22 1 Dan failed his summer exams. ______ 2 Dan has all the Tomb Raider games. ______ 3 Lara Croft studied Maths and History. ______ 4 Super Mario helps Princess Peach. -

THE MYSTERIOUS LARA CROFT: Digibimbo Vs. Digiheroine

THE MYSTERIOUS LARA CROFT: Digibimbo vs. Digiheroine 1 Rachelle Fernandez February 12th, 2001 STS145: Case History Prospectus Every once in a while, a game comes along whose influence extends beyond the gaming world and into contemporary society. One interesting and hotly debated aspect of this is the role certain video games play in gender politics. Consider the following. Scene One. A helicopter, its propellers whipping the air, zooms into the scene and drops down an agile figure onto the ground. It’s a woman, dressed in hiking shorts with pistols holstered to both thighs. The woman has landed in a dark cave and, after a cautious look around, begins to explore it, sometimes walking cautiously, other times running ahead, leaping boulders. She comes across a flare lying mysteriously on the wet cavern floor. With a happy sigh, she picks the item up. Suddenly the woman hears low grumble behind her and somersaults backwards to face an angry tiger. She whips out two automatic pistols and blasts the tiger to its death, her face contorted in a snarl. Scene Two. An exotic dancer is performing in a strip club. The camera zooms away from her to reveal an empty audience. The slogan “Where The Boys Are” is flashed across the screen while a crowd of lusty men rapidly exit the strip club in pursuit of the same woman we just saw exploring eerie caverns. 2 This “woman” isn’t even really a woman at all. She’s Lara Croft, the star in the hit video game series Tomb Raider. Lara Croft is something of a cultural icon. -

Polygons and Practice in Skies of Arcadia

Issue 02 – 2013 Journal –Peer Reviewed ZOYA STREET Gamesbrief [email protected] Polygons and practice in Skies of Arcadia This paper features research carried out at the Victoria and Albert Museum into the design history of Sega’s 2000 Dreamcast title, Skies of Arcadia (released in Ja- pan as Eternal Arcadia). It was released by Overworks, a subsidiary of Sega, at an interesting point in Japanese computer game history. A new generation of video game consoles was in its infancy, and much speculation in the industry sur- rounded how networked gaming and large, open, tridimensional game worlds would change game design in the years ahead. Skies of Arcadia is a game about sky pirates, set in a world where islands and continents foat in the sky. I became interested in this game because it was praised in critical reviews for the real sense of place in its visual design. It is a Jap- anese Role Playing Game (JRPG), meaning that gameplay focuses on exploring a series of spaces and defeating enemies in turn-based, probabilistic battles using a system similar to that established by tabletop games such as Dungeons & Dragons. This research is based on interviews with the producer Shuntaro Tanaka and lead designer Toshiyuki Mukaiyama, user reviews submitted online over the past 10 plus years, and historically informed design analysis. It is grounded in a broader study of the networks of production and consumption that surrounded and co-produced the Dreamcast as a cultural phenomenon, technological agent and played experience. Through design analysis, oral history and archival research, in this paper I will complicate notions of tridimensionality by placing a three dimensional RPG in a broader network of sociotechnical relationships. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Tomb Raider III (PC)

END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT AND LIMITED WARRANTY Tomb Raider III (PC) IMPORTANT - Please read this End User Licence Agreement (“EULA”) carefully before installing this Software Product. By installing, copying, and/or otherwise using the Software Product you agree to be bound by the terms of this EULA and we are only prepared to licence you to use the Software Product on the terms of this EULA. Before installing this Software Product please make sure that your computer meets the minimum technical specifications for the proper operation of this Software Product. YOUR PARTICULAR ATTENTION IS DRAWN TO: - THE EXCLUSION CLAUSE AND LIMITATION OF LIABILITY CONTAINED IN PARAGRAPH 9 BELOW; AND - THE PROVISIONS OF PARAGRAPHS 4 AND 5 WHICH DESCRIBE CERTAIN INFORMATION WHICH MAY BE COLLECTED, STORED AND USED BY US AS A RESULT OF YOUR INSTALLATION AND USE OF THIS SOFTWARE PRODUCT AND/OR ONLINE FEATURES AND EXPLAINS HOW YOUR PERSONAL DATA WILL BE PROTECTED. BY ACCEPTING THIS EULA AND INSTALLING THIS SOFTWARE PRODUCT YOU ARE GIVING YOUR CONSENT TO OUR COLLECTION, STORAGE, USE AND PROCESSING OF SUCH INFORMATION AND DATA IN ACCORDANCE WITH PARAGRAPH 5, OUR PRIVACY AND COOKIES POLICIES. SEL TAKES YOUR PRIVACY SERIOUSLY AND WE STRONGLY RECOMMEND YOU TAKE TIME TO READ OUR PRIVACY POLICY AND COOKIES POLICY AND PERIODICALLY CHECK FOR ANY UPDATES MADE TO IT. (i) PURCHASE OF SOFTWARE PRODUCT BY DOWNLOAD IF YOU AGREE TO BE BOUND BY THIS EULA PLEASE CLICK "I ACCEPT" AT THE END OF THIS EULA AT WHICH POINT THE SOFTWARE PRODUCT WILL BE INSTALLED ONTO YOUR HARD DRIVE. IF YOU DO NOT AGREE TO BE BOUND BY THE TERMS OF THIS EULA CLICK "NOT ACCEPTED" AND THE SOFTWARE PRODUCT WILL NOT BE LOADED ONTO YOUR HARD DRIVE AND NO LICENCE SHALL BE GRANTED TO YOU IN RESPECT OF THE SOFTWARE PRODUCT. -

Gender and Audience Reception of English-Translated Manga

Girly Girls and Pretty Boys: Gender and Audience Reception of English-translated Manga June M. Madeley University of New Brunswick, Saint John Introduction Manga is the term used to denote Japanese comic books. The art styles and publishing industry are unique enough to warrant keeping this Japanese term for what has become transnational popular culture. This paper represents a preliminary analysis of interview data with manga readers. The focus of the paper is the discussion by participants of their favourite male and female characters as well as some general discussion of their reading practices. Males and females exhibit some reading preferences that are differentiated by gender. There is also evidence of gendered readings of male and female characters in manga. Manga in Japan are published for targeted gender and age groups. The broadest divisions are between manga for girls, shōjo, and manga for boys, shōnen. Unlike Canada and the USA, manga is mainstream reading in Japan; everyone reads manga (Allen and Ingulsrud 266; Grigsby 64; Schodt, Dreamland 21). Manga stories are first serialized in anthology magazines with a specific target audience. Weekly Shōnen Jump is probably the most well known because it serializes the manga titles that have been made into popular anime series on broadcast television in North America (and other transnational markets) such as Naruto and Bleach. Later, successful titles are compiled and reprinted as tankobon (small digest-sized paperback books). The tankobon is the format in which manga are translated into English and distributed by publishers with licensing rights purchased from the Japanese copyright holders. Translated manga are also increasingly available through online scanlations produced by fans who are able to translate Japanese to English.