Grez Hidalgo2020.Pdf (1.770Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservative Manifesto

THE SCOTTISH CONSERVATIVE AND UNIONIST PARTY MANIFESTO 2016 THE SCOTTISH CONSERVATIVE AND UNIONIST PARTY MANIFESTO 2016 CHAPTER HEADING A STRONG OPPOSITION - A STRONGER SCOTLAND A STRONG OPPOSITION. A STRONGER SCOTLAND 1 THE SCOTTISH CONSERVATIVE AND UNIONIST PARTY MANIFESTO 2016 Contents RUTH DAVIDSON FOR A STRONG OPPOSITION Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 NO TO A SECOND REFERENDUM The facts ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Why it matters .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Our commitment ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 HOLDING THE SNP TO ACCOUNT Our programme for -

Judiciary Rising: Constitutional Change in the United Kingdom

Copyright 2014 by Erin F. Delaney Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 108, No. 2 JUDICIARY RISING: CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Erin F. Delaney ABSTRACT—Britain is experiencing a period of dramatic change that challenges centuries-old understandings of British constitutionalism. In the past fifteen years, the British Parliament enacted a quasi-constitutional bill of rights; devolved legislative power to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland; and created a new Supreme Court. British academics debate how each element of this transformation can be best understood: is it consistent with political constitutionalism and historic notions of parliamentary sovereignty, or does it usher in a new regime that places external, rule-of- law-based limits on Parliament? Much of this commentary examines these changes in a piecemeal fashion, failing to account for the systemic factors at play in the British system. This Article assesses the cumulative force of the many recent constitutional changes, shedding new light on the changing nature of the British constitution. Drawing on the U.S. literature on federalism and judicial power, the Article illuminates the role of human rights and devolution in the growing influence of the U.K. Supreme Court. Whether a rising judiciary will truly challenge British notions of parliamentary sovereignty is as yet unknown, but scholars and politicians should pay close attention to the groundwork being laid. AUTHOR—Assistant Professor, Northwestern University School of Law. For helpful conversations during a transatlantic visit at a very early stage of this project, I am grateful to Trevor Allan, Lord Hope, Charlie Jeffery, Lord Collins, and Stephen Tierney. -

Finance and Constitution Committee

Finance and Constitution Committee Thursday 6 September 2018 Session 5 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Thursday 6 September 2018 CONTENTS Col. EUROPEAN UNION (WITHDRAWAL) ACT 2018 ..................................................................................................... 1 FINANCE AND CONSTITUTION COMMITTEE 21st Meeting 2018, Session 5 CONVENER *Bruce Crawford (Stirling) (SNP) DEPUTY CONVENER *Adam Tomkins (Glasgow) (Con) COMMITTEE MEMBERS *Neil Bibby (West Scotland) (Lab) *Alexander Burnett (Aberdeenshire West) (Con) *Willie Coffey (Kilmarnock and Irvine Valley) (SNP) *Murdo Fraser (Mid Scotland and Fife) (Con) *Emma Harper (South Scotland) (SNP) *Patrick Harvie (Glasgow) (Green) *James Kelly (Glasgow) (Lab) *attended THE FOLLOWING ALSO PARTICIPATED: Rt Hon David Mundell MP (Secretary of State for Scotland) CLERK TO THE COMMITTEE James Johnston LOCATION The David Livingstone Room (CR6) 1 6 SEPTEMBER 2018 2 I am satisfied with the level of engagement. UK Scottish Parliament officials are in contact with their counterparts in the devolved Administrations every day, discussing Finance and Constitution our preparations for exit. For example, since January, more than 30 further deep-dive policy Committee sessions between UK Government and devolved Administration officials have been held as part of Thursday 6 September 2018 the first phase -

Crown and Sword: Executive Power and the Use of Force by The

CROWN AND SWORD EXECUTIVE POWER AND THE USE OF FORCE BY THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE CROWN AND SWORD EXECUTIVE POWER AND THE USE OF FORCE BY THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE CAMERON MOORE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Moore, Cameron, author. Title: Crown and sword : executive power and the use of force by the Australian Defence Force / Cameron Moore. ISBN: 9781760461553 (paperback) 9781760461560 (ebook) Subjects: Australia. Department of Defence. Executive power--Australia. Internal security--Australia. Australia--Armed Forces. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photographs by Søren Niedziella flic.kr/p/ ahroZv and Kurtis Garbutt flic.kr/p/9krqeu. This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents Prefatory Notes . vii List of Maps . ix Introduction . 1 1 . What is Executive Power? . 7 2 . The Australian Defence Force within the Executive . 79 3 . Martial Law . 129 4 . Internal Security . 165 5 . War . 205 6 . External Security . 253 Conclusion: What are the Limits? . 307 Bibliography . 313 Prefatory Notes Acknowledgement I would like to acknowledge the tremendous and unflagging support of my family and friends, my supervisors and my colleagues in the writing of this book. It has been a long journey and I offer my profound thanks. -

Bruce Crawford MSP Convener Devolution (Further Powers) Committee C/O Clerk to the Committee Room T3.40 the Scottish Parliament Edinburgh EH99 1SP

Bruce Crawford MSP Convener Devolution (Further Powers) Committee c/o Clerk to the Committee Room T3.40 The Scottish Parliament Edinburgh EH99 1SP 28 May 2015 Dear Bruce, I am writing to let you know that the Government has today introduced the Scotland Bill to Parliament on the first day after the Queen’s Speech marking the new legislative session. The full text of the Bill and Explanatory Notes can be found here: http://services.parliament.uk/bills/2015-16/scotland.html The introduction of the Scotland Bill marks another crucial milestone on Scotland’s journey towards becoming one of the most devolved nations in the world whilst retaining the considerable strengths and benefits of being a part of the United Kingdom. I firmly believe that the Bill will fully deliver on the Smith Commission Agreement signed up to by all five of Scotland’s main political parties. There is, of course, more work to be done on the Bill, and I am glad that both the UK Parliament and the Scottish Parliament will have ample opportunity to scrutinise and debate these measures and that the Bill will be subject to line by line scrutiny on the floor of the House in the UK Parliament. I am also sure that members across both Parliaments will want to take on board the thorough and constructive report which your Committee produced as they scrutinise the Bill’s provisions. You will note that I made significant changes to the previously published draft clauses. As I mentioned to you when we met last week, I very much look forward to discussing the Bill with your committee before the end of June. -

Introduction

Introduction This is a follow-up to my previous compilation of pro-independence articles and arguments (which can be found here). When I finished the last one, I wasn’t sure if I should or need to follow up with a second one, however, so many more articles have came out supporting independence that i thought it worthwhile creating a follow-up. The last compilation contained references up to the 24th June and this now contains references from the 25th June to around 5th September. At the time I started writing this new one, 4 weeks after I finished the last one, I had accumulated over 250 references and by the time I had finished, there were at least 800 references and 500 images! Unfortunately this has pushed the number of pages past 300, which I know is a huge amount to read in the closing weeks of the campaign (more than twice the first document) but if you can read it all, it’ll be worth it. Otherwise, dip into it and use it as a reference. By necessity, this will almost certainly be the last document I write on this subject – there are and will be many articles from both sides right up to the day of the referendum that will be relevant so please keep an eye out for them (Facebook is good for being alerted to these). However, the majority will only reinforce the arguments presented in this document (and even then this document only reinforces what was presented in the last one). As a result of the looming deadline, this compilation is likely to be a bit more rough around the edges as I wanted to finish it 2 weeks before the referendum to give time to read it. -

Adam Tomkins* in the United Kingdom And, Indeed, Across The

2017] 417 THE GUARDIANSHIP OF THE PUBLIC INTEREST: A BRITISH TALE OF CONTESTABLE ADMINISTRATIVE LAW Adam Tomkins* INTRODUCTION In the United Kingdom and, indeed, across the common law world, the constitutional relation of parliamentary government to the courts is contested. In constitutional law the controversies are relatively well known: should courts have the power to strike down legislation they hold to be incompatible with basic rights? Should legislatures be able to insist on their rights-infring- ing legislation notwithstanding a judicial ruling that there is an incompatibil- ity? Questions such as these have been at the fore of debates not only in the United Kingdom, but in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. But similar controversies abound also in administrative law and, in particular, in the re- lationship of executive to judicial decision-making. In common law parliamentary systems the executive is drawn from the legislature. In the United Kingdom all government ministers are members either of the House of Commons or of the House of Lords. To those more familiar with presidential than parliamentary democracy, this may appear at first sight to be a straightforward separation of powers problem. But the over- lap of personnel between the legislative and executive branches in common law parliamentary systems is perfectly deliberate. It occurs in order to help with—and not to hinder—the core constitutional function of holding the powerful to account. Ministers can do only what they can politically get away with. Parliamentary systems seek to find ways of allowing ministers politi- cally to get away with less. Weak ministers in a robust legislature will find that the parliamentary processes of debate, question-and-answer, and com- mittee inquiry operate so as to limit their room for maneuver. -

Annual Report 2018-19 Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body

Published 17 May 2019 SP Paper 527 5th Report 2019 (Session 5) Finance and Constitution Committee Comataidh Ionmhais is Bun-reachd Annual report 2018-19 Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Finance and Constitution Committee Annual report 2018-19, 5th Report 2019 (Session 5) Contents Introduction ____________________________________________________________1 Membership changes ____________________________________________________2 Meetings_______________________________________________________________3 (Untitled) _____________________________________________________________4 Constitution ____________________________________________________________5 Trade Bill LCM _________________________________________________________5 Common Frameworks ___________________________________________________5 Budget Scrutiny_________________________________________________________7 Pre-budget Scrutiny 2019-20______________________________________________7 Budget Scrutiny 2019-20 _________________________________________________7 Replacement of EU Structural Funds _______________________________________8 -

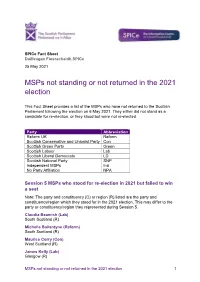

Msps Not Standing Or Not Returned in the 2021 Election

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 25 May 2021 MSPs not standing or not returned in the 2021 election This Fact Sheet provides a list of the MSPs who have not returned to the Scottish Parliament following the election on 6 May 2021. They either did not stand as a candidate for re-election, or they stood but were not re-elected. Party Abbreviation Reform UK Reform Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Con Scottish Green Party Green Scottish Labour Lab Scottish Liberal Democrats LD Scottish National Party SNP Independent MSPs Ind No Party Affiliation NPA Session 5 MSPs who stood for re-election in 2021 but failed to win a seat Note: The party and constituency (C) or region (R) listed are the party and constituency/region which they stood for in the 2021 election. This may differ to the party or constituency/region they represented during Session 5. Claudia Beamish (Lab) South Scotland (R) Michelle Ballantyne (Reform) South Scotland (R) Maurice Corry (Con) West Scotland (R) James Kelly (Lab) Glasgow (R) MSPs not standing or not returned in the 2021 election 1 Gordon Lindhurst (Con) Lothian (R) Joan McAlpine (SNP) South Scotland (R) John Scott (Con) Ayr (C) Paul Wheelhouse (SNP) South Scotland (R) Andy Wightman (Ind) Highlands and Islands (R) MSPs who were serving at the end of Parliamentary Session 5 but chose not to stand for re-election in 2021 Bill Bowman (Con) North East Scotland (R) Aileen Campbell (SNP) Clydesdale (C) Peter Chapman (Con) North East Scotland (R) Bruce Crawford (SNP) Stirling (C) Roseanna Cunningham (SNP) -

Meeting of the Parliament

Meeting of the Parliament Thursday 2 June 2016 Session 5 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Thursday 2 June 2016 CONTENTS Col. FIRST MINISTER’S QUESTION TIME ..................................................................................................................... 1 Engagements ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Scottish Trades Union Congress (Meetings) ................................................................................................ 5 Cabinet (Meetings) ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Cabinet (Meetings) ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Air Weapons (Impact of Ban) ..................................................................................................................... 14 “The Lockerbie Bombing” ........................................................................................................................... 15 Rape Victims (Support during Police Investigation) ................................................................................... 16 Local Government Reform ........................................................................................................................ -

Revue Française De Civilisation Britannique, XX-2 | 2015 Better Together and the No Campaign: from Project Fear to Grace? 2

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XX-2 | 2015 Le référendum sur l’indépendance écossaise du 18 septembre 2014 Better Together and the No Campaign: from Project Fear to Grace? Better Together et la campagne pour le 'non' Fiona Simpkins Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Electronic version URL: http://rfcb.revues.org/418 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.418 ISSN: 2429-4373 Electronic reference Fiona Simpkins, « Better Together and the No Campaign: from Project Fear to Grace? », Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XX-2 | 2015, Online since 23 July 2015, connection on 30 September 2016. URL : http://rfcb.revues.org/418 ; DOI : 10.4000/rfcb.418 This text was automatically generated on 30 septembre 2016. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Better Together and the No Campaign: from Project Fear to Grace? 1 Better Together and the No Campaign: from Project Fear to Grace? Better Together et la campagne pour le 'non' Fiona Simpkins 1 The major cross-party No campaign, Better Together, was launched a month after Yes Scotland, on 25th June 2012, at Edinburgh’s Napier University by former Chancellor of the Exchequer, Alistair Darling. Although the name chosen for the campaign, Better Together, deliberately omitted the terms Union or unionist and sounded positive and respectful of both unionists and -

Justice and Security in the United Kingdom

Tomkins, A. (2014) Justice and security in the United Kingdom. Israel Law Review. ISSN 0021-2237 Copyright © 2014 Cambridge University Press and The Faculty of Law, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91090 Deposited on: 09 April 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Justice and Security in the United Kingdom Adam Tomkins* This paper outlines the ways in which the United Kingdom manages civil litigation concerning sensitive national security material. These are: the common law of public interest immunity; the use of closed material procedure and special advocates; and the secret hearings of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal. With these existing alternatives in mind the paper analyses the background to, the reasons for, and the controversies associated with the Justice and Security Act 2013, enacted in the wake of the UK Supreme Court’s 2011 ruling in Al Rawi v Security Service. Key words: national security; civil litigation; secrecy; closed material procedure 1. INTRODUCTION How can litigation concerning national security secrets be conducted fairly? All countries committed to the rule of law must wrestle with this question, to which there is no easy answer. States need to keep secrets. Not all activity with regard to national security needs to be kept secret, but some of it does.