Mael 603,608 2020 Credit and Content Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4-.R-/3 26·6- /-.S 2T;;- S

M. P.STATE CONSUMER DISPUTES REDRESSAL COMMISSION, BHOPAL CAUSELIST FOR-16.05. 2013 Website: www.m scdrc.nic.in HoN'BLE PRESIDENT SHRI JUSTICE S.K. KULSHRESTHA & HoN'BLE MEMBERS SMT NEERJA SINGH & SHRI SUBHASH JAIN (TIME· 10·30. A ..M.). SR CASE NO. NAME OF THE PARTIES COUNSEL NAME REMARK .. NO. J FURTHER ORDERS 1 MJC 12/28 ANIL KOTHARI I VIVEK MALHOTRA SH.J.P.SHARMA I D.JOSHI .26,6,/,.3 I I 2 EXE 85/11 SMT.NASHEED AHMED ALSON SH.J.S.PARMAR DJOSHI 2D '5-/3 3 CC/l0/25 SAROJ GOYAL / JABALPUR HOSPITAL SH.D.JOSHI / A.MAHESHW ARI I R.TIW ARI 46·6-/3 4 CC/12/09 KRISHNA KUMAR / SOCIETY OF ST.JOSEPHS SH.D.JOSHI / M.CHOUKSEY I CONVENT 2'~-/3 5 CC/12/32 SAGAR AVENUE KALYANKARI SAMITI / SH.LALIT GUPTA ,I D.JOSHI I . MIS AGRAWAL CONSTRUCTION 4-. r-/3 - - _._. 6 CC/12/36 1\ KlQ " ••..H CA.."R. / IFFCO TOKIO GIC ; ~li..u.ju;sHI/ VIKAS RAI .~. 26·6- /-.S :7 A/08/1038 J3ALVANT SINGH / AJA Y MISHRA SH.VIlA Y TIWARI I ~'6-J~ -- .. I ! FA/13/672 M/SV.TRANS INDIA LTDJSAMEERPATEL SH.SURESH INDOREKAR I . 24.08.1.1 i 8 i I 9 FA/I 0/217 IFFCO TOKIO GIC 1 JITENDRA PATIDAR SH.VlKAS RAIl SAMEER SAHU 2t;;- S -/~ 10 FA/l3/800/ S.R.FALKE 1 DA VINDER PAL SINGH SH.DJOSHI/ ;z". ()r 6 ~/3 J FA/13/803 S.R.FALKE 1 PRABHJEET S.CHAWLA SH.DJOSHI/ 2/0 -6 ·8 ~ I MOTION HEARING MATTERS ! \ 1 ~A!12/12741 MANOHARCHOURASIA/NAGARPALIKA ISH. -

Literatura Orientu W Piśmiennictwie Polskim XIX W

Recenzent dr hab. Kinga Paraskiewicz Projekt okładki Igor Stanisławski Na okładce wykorzystano fragment anonimowego obrazu w stylu kad żarskim „Kobieta trzymaj ąca diadem” (Iran, poł. XIX w.), ze zbiorów Państwowego Muzeum Ermita żu, nr kat. VP 1112 Ksi ąż ka finansowana w ramach programu Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wy ższego pod nazw ą „Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” w latach 2013-2017 © Copyright by individual authors, 2016 ISBN 978-83-7638-926-4 KSI ĘGARNIA AKADEMICKA ul. św. Anny 6, 31-008 Kraków tel./faks 12-431-27-43, 12-421-13-87 e-mail: [email protected] Ksi ęgarnia internetowa www.akademicka.pl Spis tre ści Słowo wst ępne . 7 Ignacy Krasicki, O rymotwórstwie i rymotwórcach. Cz ęść dziewi ąta: o rymotwórcach wschodnich (fragmenty) . 9 § I. 11 § III. Pilpaj . 14 § IV. Ferduzy . 17 Assedy . 18 Saady . 20 Suzeni . 22 Katebi . 24 Hafiz . 26 § V. O rymotwórstwie chi ńskim . 27 Tou-fu . 30 Lipe . 31 Chaoyung . 32 Kien-Long . 34 Diwani Chod ża Hafyz Szirazi, zbiór poezji Chod ży Hafyza z Szyrazu, sławnego rymotwórcy perskiego przez Józefa S ękowskiego . 37 Wilhelm Münnich, O poezji perskiej . 63 Gazele perskiego poety Hafiza (wolny przekład z perskiego) przeło żył Jan Wiernikowski . 101 Józef Szujski, Rys dziejów pi śmiennictwa świata niechrze ścija ńskiego (fragmenty) . 115 Odczyt pierwszy: Świat ras niekaukaskich z Chinami na czele . 119 Odczyt drugi: Aryjczycy. Świat Hindusów. Wedy. Ksi ęgi Manu. Budaizm . 155 Odczyt trzeci: Epopeja indyjskie: Mahabharata i Ramajana . 183 Odczyt czwarty: Kalidasa i Dszajadewa [D źajadewa] . 211 Odczyt pi ąty: Aryjczycy. Lud Zendów – Zendawesta. Firduzi. Saadi. Hafis . 233 Piotr Chmielowski, Edward Grabowski, Obraz literatury powszechnej w streszczeniach i przekładach (fragmenty) . -

Sanskrutha Bharathi, New Jersey & Sangam Festival

Sanskrutha Bharathi, New Jersey & Sangam Festival- Princeton, New Jersey hosted a seminar and performance - commemorating the 1000th year of the Kashmirian genius Acharya Abhinavagupta on Saturday, April 8th 2017. The program opened with a brief prayer followed by a paper presentation by Bharatanatyam exponent and scholar Bala Devi Chandrashekar on Sri Abhinavagupta's commentary on Bharata muni's treatise "Natya shastra". The presentation stressed the immense value of understanding Abhinava Gupta's commentary "Abhinava Bharathi" to comprehend Natya Sastra. The Key takeaways from Bala Devi's presentation - Abhinava Gupta's two major works on aesthetics are - Dhvanyaloka -locana and Abhinava Bharati, they point towards his quest into the nature of aesthetic experience. In both these works Abhinava Gupta suggests that aesthetic experience is something beyond worldly experience, and has used the word ‘Alaukika’ to distinguish the former feeling from the mundane latter ones. He subscribes to the theory of Rasa Dhvani and thus entered the ongoing aesthetic debate on nature of aesthetic pleasure. Bharatha in Natyashastra, his pioneering work on Indian dramatics, mentions eight rasas and says rasa is produced when ‘Vibhaava’, Anubhava and Vyabhichari bhava come together. According to Abhinavagupta, the aesthetic experience is the manifestation of the self. It is similar to the spiritual experience as one transcends the limitations of one's limited self because of the process of universalisation taking place during the aesthetic contemplation of characters depicted in the work of art. Abhinavagupta maintains that this rasa is the supreme good of all literature. Abhinavagupta extended the eight rasas categorized by Bharata, by adding one more to the list, the Shanta rasa. -

The Semiotics of Axiological Convergences and Divergences1 Ľubomír Plesník

DOI: 10.2478/aa-2020-0004 West – East: The semiotics of axiological convergences and divergences1 Ľubomír Plesník Professor Ľubomír Plesník works as a researcher and teacher at the Institute of Literary and Artistic Communication (from 1993 to 2003 he was the director of the Institute, and at present he is the head of the Department of Semiotic Studies within the Institute). His research deals primarily with problems of literary theory, methodology and semiotics of culture. Based on the work of František Miko, he has developed concepts relating to pragmatist aesthetics, reception poetics and existential semiotics with a special focus on comparison of Western and oriental epistemes (Pragmatická estetika textu 1995, Estetika inakosti 1998, Estetika jednakosti 2001, Tezaurus estetických výrazových kvalít 2011). Abstract: This study focuses on the verbal representation of life strategies in Vetalapanchavimshati, an old Indian collection of stories, which is part of Somadeva’s Kathasaritsagara. On the basis of the aspect of gain ~ loss, two basic life strategies are identified. The first one, the lower strategy, is defined by an attempt to obtain material gain, which is attained at the cost of a spiritual loss. The second one, the higher strategy, negates the first one (spiritual gain attained at the cost of a material loss) and it is an internally diversified series of axiological models. The core of the study explains the combinatorial variants which, in their highest positions, even transcend the gain ~ loss opposition. The final part of the study demonstrates the intersections between the higher strategy and selected European cultural initiatives (gnosis). 1. Problem definition, area of concern and material field Our goal is to reflect on the differences and intersections in the iconization of gains and losses in life between the Western and Eastern civilizations and cultural spheres. -

2348-7666; Vol.3, Issue-7(4), July, 2016 Impact Factor: 3.656; Email: [email protected]

International Journal of Academic Research ISSN: 2348-7666; Vol.3, Issue-7(4), July, 2016 Impact Factor: 3.656; Email: [email protected] In-charge of English Department, Ideal College of Arts & Sciences (A), Kakinada It may not be hyperbolic to As an educationist, reformer say that there may not be such a great politician, and follower of Brahmo Samaj, man as Tagore. Just two points are worth he assimilated the best in the oriental enough to mention here. He was the tradition. fought against the bigotry and author of our National Anthem . At least inertia of conventional Hinduism. He 40 crore Indians stand up to respect the relinquished his knight hood. National Anthem, when it is sung or As a painter, Tagore struck the played on music. He was the author of golden mean between traditionalism and the National Anthem of Bangladesh also. impressionism. “Genuinely original, There also a good number of people genuinely native”. Again, as a musician respect their National Anthem by he established a pleasing synthesis standing in attention. What else would between classical and light music, the dead soul requires to be joyous, if at Rabidra Sangeet will enjoy eternal youth. all we have belief on soul. As a dramatist, he started with verse- Above all he was the first Asian plays and ended with dance drama. He to receive the Noble Prize for English was also an actor. literature in 1913. The writing of Tagore began his poetic career at Gitanjali, written in a foreign language the age of eight and continued it until the was preferred to the writings of even the last day of his eventful life. -

Aesthetic Philosophy of Abhina V Agupt A

AESTHETIC PHILOSOPHY OF ABHINA V AGUPT A Dr. Kailash Pati Mishra Department o f Philosophy & Religion Bañaras Hindu University Varanasi-5 2006 Kala Prakashan Varanasi All Rights Reserved By the Author First Edition 2006 ISBN: 81-87566-91-1 Price : Rs. 400.00 Published by Kala Prakashan B. 33/33-A, New Saket Colony, B.H.U., Varanasi-221005 Composing by M/s. Sarita Computers, D. 56/48-A, Aurangabad, Varanasi. To my teacher Prof. Kamalakar Mishra Preface It can not be said categorically that Abhinavagupta propounded his aesthetic theories to support or to prove his Tantric philosophy but it can be said definitely that he expounded his aesthetic philoso phy in light of his Tantric philosophy. Tantrism is non-dualistic as it holds the existence of one Reality, the Consciousness. This one Reality, the consciousness, is manifesting itself in the various forms of knower and known. According to Tantrism the whole world of manifestation is manifesting out of itself (consciousness) and is mainfesting in itself. The whole process of creation and dissolution occurs within the nature of consciousness. In the same way he has propounded Rasadvaita Darsana, the Non-dualistic Philosophy of Aesthetics. The Rasa, the aesthetic experience, lies in the conscious ness, is experienced by the consciousness and in a way it itself is experiencing state of consciousness: As in Tantric metaphysics, one Tattva, Siva, manifests itself in the forms of other tattvas, so the one Rasa, the Santa rasa, assumes the forms of other rasas and finally dissolves in itself. Tantrism is Absolute idealism in its world-view and epistemology. -

(Dr) Utpal K Banerjee

About the Book IGNCA is a treasure-trove of cultural artifacts including a rich repository of Video documentaries (published) and Audio and Video DVDs (unpublished). This book – based on the author’s two-year project -- envisions an on-line A-V cultural archive KALASAMPADA that consists of A-V materials stored at IGNCA for the categories of: Interviews; Ritual Documentation; Archaeological Sites and Walk-through; Events; Festivals; Performances (music-dance-theatre-puppetry-mime); Lectures; Seminars; and Workshops. In order to make such a wide variety of materials available on-line – initially on the Intranet, subsequently on a potential Extranet, and eventually (although very selectively) on the Internet – the following digitisation road-map is observed in the project: Conversion of primary A-V materials from analogue to digital format; Creation of data sheets for metadata tagging, following the international standard of Dublin Core Metadata Element Set (DCMES); Integration of metadata with primary A-V material in IGNCA’s Intranet; Access and retrieval by “simple search” with keywords for casual browsers and “advanced search” for users, researchers and scholars with reference to groups of keywords from the intranet. The objectives of the project of on-line A-V cultural archive are: to bring it into public domain; to make it inter-active for scholars; and to make it internationally compatible. Basic advantages of such a project are really five-fold. First, a digital A-V archive assures the near permanent durability of the A-V material. Secondly, it allows need-based quality enhancement. Thirdly, an archive of this kind makes room for highly economic storage of vulnerable Audio and Video files. -

PAPER VI UNIT I Non-Fictional Prose—General

PAPER VI UNIT I Non-fictional Prose—General Introduction, Joseph Addison’s The Spectator Papers: The Uses of the Spectator, The Spectator’s Account of Himself, Of the Spectator 1.1. Introduction: Eighteenth Century English Prose The eighteenth century was a great period for English prose, though not for English poetry. Matthew Arnold called it an "age of prose and reason," implying thereby that no good poetry was written in this century, and that, prose dominated the literary realm. Much of the poetry of the age is prosaic, if not altogether prose-rhymed prose. Verse was used by many poets of the age for purposes which could be realized, or realized better, through prose. Our view is that the eighteenth century was not altogether barren of real poetry. Even then, it is better known for the galaxy of brilliant prose writers that it threw up. In this century there was a remarkable proliferation of practical interests which could best be expressed in a new kind of prose-pliant and of a work a day kind capable of rising to every occasion. This prose was simple and modern, having nothing of the baroque or Ciceronian colour of the prose of the seventeenth-century writers like Milton and Sir Thomas Browne. Practicality and reason ruled supreme in prose and determined its style. It is really strange that in this period the language of prose was becoming simpler and more easily comprehensible, but, on the other hand, the language of poetry was being conventionalized into that artificial "poetic diction" which at the end of the century was so severely condemned by Wordsworth as "gaudy and inane phraseology." 1.2. -

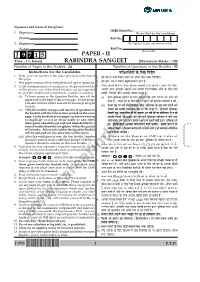

Copy of OMR Sheet on Conclusion of Examination

Signature and Name of Invigilator OMR Sheet No. : .......................................................... 1. (Signature) (To be filled by the Candidate) (Name) Roll No. 2. (Signature) (In figures as per admission card) (Name) Roll No. (In words) J 9715 PAPER - II Time : 1¼ hours] RABINDRA SANGEET [Maximum Marks : 100 Number of Pages in this Booklet : 24 Number of Questions in this Booklet : 50 Instructions for the Candidates ÂÚUèÿææçÍüØô¢ ·ð¤ çÜ° çÙÎðüàæ 1. Write your roll number in the space provided on the top of 1. §â ÂëDU ·ð¤ ª¤ÂÚU çÙØÌ SÍæÙ ÂÚU ¥ÂÙæ ÚUôÜU ÙÕÚU çÜç¹°Ð this page. 2. This paper consists of fifty multiple-choice type of questions. 2. §â ÂýàÙ-Âæ ×𢠿æâ Õãéçß·¤ËÂèØ ÂýàÙ ãñ´Ð 3. At the commencement of examination, the question booklet 3. ÂÚUèÿææ ÂýæÚUÖ ãôÙð ÂÚU, ÂýàÙ-ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ¥æ·¤ô Îð Îè ÁæØð»èÐ ÂãÜðU ÂUæ¡¿ ç×ÙÅU will be given to you. In the first 5 minutes, you are requested ¥æ·¤ô ÂýàÙ-ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ¹ôÜÙð ÌÍæ ©â·¤è çÙÙçÜç¹Ì Áæ¡¿ ·ð¤ çÜ° çÎØð to open the booklet and compulsorily examine it as below : ÁæØð¢»ð, çÁâ·¤è Áæ¡¿ ¥æ·¤ô ¥ßàØ ·¤ÚUÙè ãñ Ñ (i) To have access to the Question Booklet, tear off the (i) ÂýàÙ-ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ¹ôÜÙð ·ð¤ çÜ° ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ÂÚU Ü»è ·¤æ»Á ·¤è âèÜ ·¤æð paper seal on the edge of this cover page. Do not accept ȤæǸ Üð¢UÐ ¹éÜè ãé§ü Øæ çÕÙæ SÅUè·¤ÚU-âèÜU ·¤è ÂéçSÌ·¤æ Sßè·¤æÚU Ù ·¤Úð¢UÐ a booklet without sticker-seal and do not accept an open booklet. -

Sharanagati, Year Third

1. Sentimentalism and Compassion (from lecture of B.K.Tirtha Maharaj, 27.02.2007, Sofia) “O descendent of Bharata, he who dwells in the body can never be slain. Therefore you need not grieve for any living being.” 1 This verse actually gives the definition of sentimentalism. Because one definition of being sentimental is when you try to give more compassion to a living entity than God. Although this is a very difficult definition, if you try to give more compassion to an entity than God, then this is sentimental. How to understand this? This definition is very much connected with karma. Karma means action and reaction, you get what you deserve. You sow the wind – you reap the tempest. Whatever we do, there will be some reaction. This is one element of this question. So, fate is written on the foreheads of people. Whatever happiness, success, suffering and failure is awaiting you in this lifetime, it is given in the beginning. So, do not revolt against your fate. Actually fate is not a punishment, but fate is a chance to fulfill our progress. Therefore we should be thankful for getting all the different opportunities in our lifetime. Of course, during our spiritual progress, we must learn what is compassion. But remember the definition: sentimental means you try to be over-compassionate – compassionate over the path, over karma, over the fate of people. Of course, it does not mean “do not give help” if help is needed. But there are certain things that we cannot change. We should identify our limits. -

Jabalpur Before the Lok Adalat of Mp High Court

HIGH COURT OF MADHYA PRADESH : JABALPUR BEFORE THE LOK ADALAT OF M.P. HIGH COURT LEGAL SERVICES COMMITTEE, JABALPUR BENCH - I (Time 4:30 PM) Daily Cause List dated : 17-02-2016 BEFORE: HON'BLE MISS JUSTICE VANDANA KASREKAR VENUE : "CONFERENCE HALL, SOUTH BLOCK", HIGH COURT OF M.P., JABALPUR PRE-SITTING CASES RELATED TO UNITED INDIA INSURANCE CO. LTD. SN Case No Petitioner / Respondent Petitioner/Respondent Advocate 1 MA 563/2005 KANCHHEDILAL &ANR. NARENDRA CHOUHAN, VINOD PRAJAPATI, S.SHARMA Versus RAJENDRA PRASAD JAISWAL & ANR. KL.RAJ, SURESH RAJ(2), , GAJENDRA SINGH(R1), SANJAY KUMAR SAINI 2 MA 751/2008 SMT.MAYABAI SATISH SHRIVASTAVA, VIJAY PASI, VIJAY KHARE Versus RAJENDRA KUMAR , (R-5), NARINDER PAL SINGH RUPRAH[R-6], AMRIT KAUR RUPRAH[R-6], SITARAM GARG[R-6], PUSHPANJALI KUMAR MISHRA[R-2], DEEPCHAND GUPTA[R-3] 3 MA 1886/2008 DINESH PRASAD TRIPATHI SHARAD GUPTA Versus VED PRAKASH PATHAK VK DWIVEDI(R5), P.PAREEK, SK.MISHRA, P.SAHU[2], D.C.GUPTA,AJAY PRATAP SINGH,N.K.GUPTA,K.LAKHERA(R3 4 MA 1981/2008 IMARTI BAI BR.KOSHTA, MANOJ YADAV Versus LOTAN SINGH , DIWAKAR NATH SHUKLA[R-6], GYANENDRA KUMAR MISHRA[R-6] 5 MA 4985/2008 SUNIL SHREEPAL ABHAY KUMAR JAIN, SMT. DEVIKA SINGH Versus DEVLAL YADAV , DEEPCHAND GUPTA[R-3] 6 MA 5149/2008 SMT.MADHURI TIWARI(SHARMA) GOPAL SHARIWAS, A.D.MISHRA Versus MOHD.AYUB KHAN , DEEPCHAND GUPTA[R-3] 7 MA 3782/2009 SMT.MULIYA BAI SUSHIL TIWARI, RAVENDRA TIWARI, VIVEK AGARWAL Versus SHIV PRASAD RK.SAMAIYA, SHAILENDRA SAMAIYA, RAJROOP PATEL[3] 8 MA 5045/2009 RAMCHARAN NITIN GUPTA, ABHISHEK GOSWAMY, VISHAL MOURYA, SHASHANK SHEKHAR Versus ABRAR KHAN VK.TRIVEDI[3] 9 MA 1670/2010 ASHOKMAL MALVIYA (DECEASED) LRS. -

UGC MHRD E Pathshala

UGC MHRD e Pathshala Subject: English Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Paper 09: Comparative Literature: Drama in India Paper Coordinator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Module 09:Theatre: Architecture, Apparatus, Acting; Censorship and Spectatorship; Translations and Adaptations Content Writer: Mr. Benil Biswas, Ambedkar University Delhi Content Reviewer: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Language Editor: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Introduction: To be a painter one must know sculpture To be an architect one must know dance Dance is possible only through music And poetry therefore is essential (Part 2 of Vishnu Dharmottara Purana, an exchange between the sage Markandya and King Vajra)1 Quite appropriately Theatre encompasses all the above mentions arts, which is vital for an individual and community’s overall development. India is known for its rich cultural heritage has harnessed the energy of theatrical forms since the inception of its civilization. A rich cultural heritage of almost 3000 years has been the nurturing ground for Theatre and its Folk forms. Emerging after Greek and Roman theatre, Sanskrit theatre closely associated with primordial rituals, is the earliest form of Indian Theatre. Ascribed to Bharat Muni, ‘Natya Sastra or Natyashastra’2 is considered to be the initial and most elaborate treatise on dramaturgy and art of theatre in the world. It gives the detailed account of Indian theatre’s divine origin and expounds Rasa. This text becomes the basis of the classical Sanskrit theatre in India. Sanskrit Theatre was nourished by pre-eminent play-wrights like Bhasa, Kalidasa, Shudraka, Vishakadatta, Bhavabhuti and Harsha.3 This body of works which were sophisticated in its form and thematic content can be equaled in its range and influence with the dramatic yield of other prosperous theatre traditions of the world like ancient Greek theatre and Elizabethan theatre.