Fellowship 21: Gallery Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silver Eye 2018 Auction Catalog

Silver Eye Benefit Auction Guide 18A Contents Welcome 3 Committees & Sponsors 4 Acknowledgments 5 A Note About the Lab 6 Lot Notations 7 Conditions of Sale 8 Auction Lots 10 Glossary 93 Auction Calendar 94 B Cover image: Gregory Halpern, Untitled 1 Welcome Silver Eye 5.19.18 11–2pm Benefit Auction 4808 Penn Ave Pittsburgh, PA AUCTIONEER Welcome to Silver Eye Center for Photography’s 2018 Alison Brand Oehler biennial Auction, one of our largest and most important Director of Concept Art fundraisers. Proceeds from the Auction support Gallery, Pittsburgh exhibitions and artists, and keep our gallery and program admission free. When you place a bid at the Auction, TICKETS: $75 you are helping to create a future for Silver Eye that Admission can be keeps compelling, thoughtful, beautiful, and challenging purchased online: art in our community. silvereye.org/auction2018 The photographs in this catalog represent the most talented, ABSENTEE BIDS generous, and creative artists working in photography today. Available on our website: They have been gathered together over a period of years silvereye.org/auction2018 and represent one of the most exciting exhibitions held on the premises of Silver Eye. As an organization, we are dedicated to the understanding, appreciation, education, and promotion of photography as art. No exhibition allows us to share the breadth and depth of our program as well as the Auction Preview Exhibition. We are profoundly grateful to those who believe in us and support what we bring to the field of photography. Silver Eye is generously supported by the Allegheny Regional Asset District, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, The Heinz Endowments, The Pittsburgh Foundation, The Fine Foundation, The Jack Buncher Foundation, The Joy of Giving Something Foundation, The Hillman Foundation, an anonymous donor, other foundations, and our members. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Stan Magazynu Caĺ†Oĺıäƒ Lp Cd Sacd Akcesoria.Xls

CENA WYKONAWCA/TYTUŁ BRUTTO NOŚNIK DOSTAWCA ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST 159,99 SACD BERTUS ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST (NUMBERED 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - BROTHERS AND SISTERS (NUMBE 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - EAT A PEACH (NUMBERED LIMIT 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - IDLEWILD SOUTH (GOLD CD) 129,99 CD GOLD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ASIA - ASIA 179,99 SACD BERTUS BAND - STAGE FRIGHT (HYBRID SACD) 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - MUSIC FROM BIG PINK (NUMBERED LIMITED 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - THE LAST WALTZ (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITI 179,99 2 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BASIE, COUNT - LIVE AT THE SANDS: BEFORE FRANK (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BIBB, ERIC - BLUES, BALLADS & WORK SONGS 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - JUST LIKE LOVE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - RAINBOW PEOPLE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - GOOD STUFF 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - SPIRIT & THE BLUES 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BLIND FAITH - BLIND FAITH 159,99 SACD BERTUS BOTTLENECK, JOHN - ALL AROUND MAN 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 CAMEL - RAIN DANCES 139,99 SHMCD BERTUS CAMEL - SNOW GOOSE 99,99 SHMCD BERTUS CARAVAN - IN THE LAND OF GREY AND PINK 159,99 SACD BERTUS CARS - HEARTBEAT CITY (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITION HY 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS AFTER HOURS (NUMBERED LI 99,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS OF RAY CHARLES (NUMBERED 129,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY -

Publication 2

KHU_playbill_cat.indd 1 6/4/14 2:44 PM Contents FORWARD..............................................4 Rebecca Ruth Hart ANCIENT EVENINGS.........................6 REN..........................................................8 KHU........................................................11 OSIRIS IN DETROIT.............................12 Angus Cook MAP........................................................16 LIBRETTO...........................................20 NOTES ON THE MUSIC...................27 Jonathan Bepler and Shane Anderson PROFILES.............................................28 CAST AND CREW..............................30 WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST.........32 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION.......35 “I believe in the practice and philosophy of what we have agreed to call magic, in what I must call the evocation of spirits, though I do not know what they are, in the power of creating magical illusions, in the visions of truth in the depths of the mind when the eyes are closed; and I believe…that the borders of our mind are ever shifting, and that many minds can flow into one another, as it were, and create or reveal a single mind, a single energy…and that our memories are part of one great memory, the memory of Nature herself.” W.B. Yeats Ideas of Good and Evil Epigraph to Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evenings The use of any recording device, either audio or video, and the taking of photographs, either with or without flash, is strictly prohibited. Please turn cellular phones off, as it interferes with audio recording equipment and telecommunications. Thank you. KHU_playbill_cat.indd 2-1 6/4/14 2:44 PM KHU_playbill_cat.indd 2-3 6/4/14 2:44 PM Forward With the promise of full support from Henry Ford’s son Edsel, William Rebecca Ruth Hart Valentiner, then director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, met with Rivera in San Francisco in 1930. -

National Endowment for the Arts Winter Award Announcement for FY 2021

National Endowment for the Arts Winter Award Announcement for FY 2021 Artistic Discipline/Field List The following includes the first round of NEA recommended awards to organizations, sorted by artistic discipline/field. All of the awards are for specific projects; no Arts Endowment funds may be used for general operating expenses. To find additional project details, please visit the National Endowment for the Arts’ Grant Search. Click the award area or artistic field below to jump to that area of the document. Grants for Arts Projects - Artist Communities Grants for Arts Projects - Arts Education Grants for Arts Projects - Dance Grants for Arts Projects - Design Grants for Arts Projects - Folk & Traditional Arts Grants for Arts Projects - Literary Arts Grants for Arts Projects - Local Arts Agencies Grants for Arts Projects - Media Arts Grants for Arts Projects - Museums Grants for Arts Projects - Music Grants for Arts Projects - Musical Theater Grants for Arts Projects - Opera Grants for Arts Projects - Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Grants for Arts Projects - Theater Grants for Arts Projects - Visual Arts Literature Fellowships: Creative Writing Literature Fellowships: Translation Projects Research Grants in the Arts Research Labs Applications for these recommended grants were submitted in early 2020 and approved at the end of October 2020. Project descriptions are not included above in order to accommodate any pandemic-related adjustments. Current information is available in the Recent Grant Search. This list is accurate as of 12/16/2020. Grants for Arts Projects - Artist Communities Number of Grants: 36 Total Dollar Amount: $685,000 3Arts, Inc $14,000 Chicago, IL Alliance of Artists Communities $25,000 Providence, RI Atlantic Center for the Arts, Inc. -

STORNOWAY Farewell

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 260 March Oxford’s Music Magazine 2017 “I can’t imagine there are many better cities to be in a band. Our fans have remained unbelievably loyal. We are extremely proud to be an Oxford band.” farewell STORNOWAY Their final show Their final interview Also in this issue: Introducing THE GREAT WESTERN TEARS TRUCK, COMMON PEOPLE, CORNBURY line-ups announced plus All your Oxford music news and reviews, and six pages of local gigs for March NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk PMT launches its new superstore this month with special guests and live sets from local acts. Gaz Coombes and Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood will cut the SEAN PAUL AND PETE TONG’S HERITAGE ORCHESTRA ribbon on the new store, at the new will headline this year’s Common People. site further along Cowley Road, on Jamaican dancehall star Paul tops the Saturday night bill at the Saturday 4th March. The shop will 30,000-capacity event in South Park on the 27th May, while Radio 1 DJ THE JACKSONS will play a show be three times the size of its existing Tong joins forces with The Heritage Orchestra (pictured) and conductor at Blenheim Palace this summer. store, which has been a staple of the Jules Buckley for an orchestral set of Ibiza dance classics on Sunday 28th. In celebration of their 50th east Oxford music scene for 20 years, After last year’s successful inaugural event, headlined by Duran Duran and anniversary, the legendary Motown featuring expanded guitar, drum, Primal Scream, Common People makes a return to the heart of Oxford. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

Radial Survey Destiny of a Place —Vol.1 Silver Eye Center for Photography

Radial Survey Destiny of a Place —Vol .1 Silver Eye Center for Photography Radial Survey Destiny of a Place —Vol .1 Silver Eye Center for Photography Radial Survey Vol.1 5 Letter from the Director (David Oresick) 8 The Destiny of a Place (Leo Hsu) 20 The Identity Trap (Jessica Beck) 22 Eva O’Leary 30 Brendan George Ko 42 Lydia Panas 50 Nydia Blas 60 Construction and Revelation (Anna Lee) 62 Susan Worsham 72 Ahndraya Parlato 86 Nando Alvarez-Perez 94 Held in Abeyance (Miranda Mellis) 96 Melissa Catanese 104 The Destiny of This Place (Ashley McNelis) 106 Morgan Ashcom 120 Jacob Koestler 128 Jared Thorne 140 Corine Vermeulen 153 Contributor Bios 156 Colophon Radial Survey Vol.1 Contents 3 Five years ago, after more than a decade in Chicago I moved back home to my hometown of Pittsburgh. I immediately fell back in love with this city and the creative community here. The artists I met embodied Pittsburgh to me; they were passionate, hard working, unpretentious, and beyond talented. They were also all in Pittsburgh because they were serious about creating a life that allowed them time, space and energy to create. ¶ I still saw plenty of my old friends from Chicago because they would stop and stay for the night on their way to New York, as Pittsburgh is nearly the exact halfway point on the pilgrimage from one art meca to the other. I loved hosting these visitors and sharing Pittsburgh with new and old friends. Everyone who came through was blown away by the small-and-mighty arts scene here ¶ As I learned more about the regions surrounding Pittsburgh Radial Survey Vol.1 Letter from the Director, David Oresick 5 I came to realize this attitude and work This circle represents a funny, arbitrary, ethic stretched beyond South Western and real community. -

Discos Internacionales

ARTISTA DISCO DESCRIPCIÓN 2ND GRADE HIT TO HIT A GIRL CALLED EDDY BEEN AROUND AC/DC POWERAGE AIDAN KNIGHT´S AIDAN KNIGHT´S CLEAR/BLACK VINYL AL GREEN IM STILL IN LOVE WITH YOU ALABAMA SHAKES SOUND AND COLOR CLEAR VINYL ALEX CHILTON FREE AGAIN: THE 1970 SESSIONS VINILO ROJO TRANSLÚCIDO ALGIERS THE UNDERSIDE OF POWER ED. LMITADA. CREAM VINYL ALGIERS THERE IS NO YEAR ED. LIMITADA CLEAR VINYL + FLEXI ALICE COOPER KILLER ALICE COOPER ZIPPER CATCHES SKIN CLEAR/BLACK SWIRL VINYL ALL NIGHT LONG NOTHERN SOUL FLOOR FILLERS RECOPILATORIO ALL THEM WITCHES ALL THEM WITCHES VINYL COLOR ALLAH LAS CALICO REVIEW ALLAH LAS DEVENDRA ALLAH LAS LAHS VINYL ORANGE ALLAH LAS WORSHIP THE SUN ALLIE X CAPE GOD ALT-J REDUXER ALT-J THIS IS ALL YOURS COLOUR-SHUFFLED VINYL (RED, YELLOW, BLUE, GREEN) AMNESIA SCANNER TEARLESS AMOK ATOMS FOR PEACE AMY WINEHOUSE FRANK AMYL AND THE SNIFFERS LIVE AT THE CROXTON SINGLE 7" ANDREW BIRD ARE YOU SERIOUS ANGEL OLSEN ALL MIRRORS ANGEL OLSEN BURN YOUR FIRE FOR NO WITNESS ANGEL OLSEN MY WOMAN ANGEL OLSEN PHASES ANGEL OLSEN WHOLE NEW MESS ANGELUS APATRIDA CABARET DE LA GUILLOTINE ANGELUS APATRIDA GIVE 'EM WAR ANGUS & JULIA STONE ANGUS & JULIA STONE ANGUS & JULIA STONE A BOOK LIKE THIS ANGUS & JULIA STONE SNOW ANNA CALVI HUNTED RED VINYL ANTIFLAG AMERICAN FALL ANTIFLAG AMERICAN RECKONING ANTIFLAG AMERICAN SPRING ARCA KICK´I ARCA MUTANT DOUBLE RED VINYL ARCADE FIRE FUNERAL ARCADE FIRE NEON BIBLE ARCTIC MONKEYS AM ARCTIC MONKEYS FAVOURITE WORST NIGHTMARE ARCTIC MONKEYS SUCK IT AND SEE ARCTIC MONKEYS TRANQUILITY BASE HOTEL+ CASINO ARETHA -

Alison Goldfrapp on Paying Attention to Detail

January 23, 2017 - As part of the English duo Goldfrapp, musician, producer and acclaimed vocalist Alison Goldfrapp has released seven albums over the past 18 years. The new Goldfrapp record, Silver Eye, will be released on March 31st. As told to T. Cole Rachel, 2856 words. Tags: Music, Process, Multi-tasking. Alison Goldfrapp on paying attention to detail The musician on feeding your creative self, the value of fucking up, and being mindful of everything—even the boring stuff. It’s been nearly four years since the last Goldfrapp record. At this point, how do you decide when it’s time to make something new? And what’s going on with you creatively in the interim? We had a break after that last one, which was good for us. We were still working though. We went away and did the music for a play at the National Theatre. The piece was Medea, which is a Greek tragedy and very traditional, but was updated for this production. Carrie Cracknell was the director. We spent about a year doing that—working with a chorus of 13 women vocalists—which was great. It was wonderful to be doing something completely different and helps shake up the way you think about things when you go back to doing your own work. Then, we just took our time and we didn’t rush into anything. And when we did get started, it took quite a while to get into the groove with it. We also took a while to think about what kind of sound we wanted to make, and as a result the process became much more electronic. -

Birmingham Cover November 2017 .Qxp Birmingham Cover 20/10/2017 15:21 Page 1

Birmingham Cover November 2017 .qxp_Birmingham Cover 20/10/2017 15:21 Page 1 DANNY MAC AT Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands BIRMINGHAM HIPPODROME BIRMINGHAM WHAT’S ON NOVEMBER 2017 NOVEMBER ON WHAT’S BIRMINGHAM Birmingham ISSUE 383 NOVEMBER 2017 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD OnBirminghamWhatsOn.co.uk PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART TWITTER: @WHATSONBRUM @WHATSONBRUM FACEBOOK: @ WHATSONBIRMINGHAM @ FACEBOOK: BIRMINGHAMWHATSON.CO.UK Photo: Manuel Vason Manuel Photo: (IFC) Birmingham.qxp_Layout 1 20/10/2017 11:34 Page 1 Contents November Birmingham.qxp_Layout 1 23/10/2017 17:24 Page 2 November 2017 Contents The Nutcracker - BRB’s magical production returns to the Hippodrome page 20 Danny Mac Margaret Cho The Hairy Bikers the list stretches himself as a performer American comedian brings cook up a treat at the Your 16-page in Sunset Boulevard Fresh Off The Bloat to Brum BBC Good Food Show week-by-week listings guide feature page 8 page 23 page 49 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 15. Music 22. Comedy 24. Theatre 41. Film 44. Visual Arts 47. Events @whatsonbrum fb.com/whatsonbirmingham @whatsonbirmingham Birmingham What’s On Magazine Birmingham What’s On Magazine Birmingham What’s On Magazine Managing Director: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 WhatsOn Editorial: Lauren Foster [email protected] 01743 281707 -

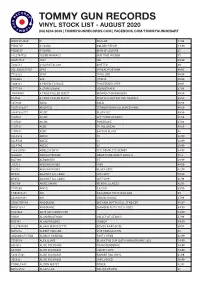

Vinyl Stock List - August 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | Tommygunrecords.Com | Facebook.Com/Tommygunhobart

TOMMY GUN RECORDS VINYL STOCK LIST - AUGUST 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | TOMMYGUNRECORDS.COM | FACEBOOK.COM/TOMMYGUNHOBART WARPLP302X !!! WALLOP 47.99 PIE027LP #1 DADS GOLDEN REPAIR 44.99 PIE005LP #1 DADS MAN OF LEISURE 35 8122794723 10,000 MANIACS OUR TIME IN EDEN 45 SSM144LP 1927 ISH 39.99 7202581 24 CARAT BLACK GHETTO 69 USI_B001655701 2PAC 2PACALYPSE NOW 49.95 7783828 2PAC THUG LIFE 49.99 FWR004 360 UTOPIA 49.99 5809181 A PERFECT CIRCLE THIRTEENTH STEP 49.95 6777554 A STAR IS BORN SOUNDTRACK 67.99 JIV41490.1 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST MIDNIGHT MARAUDERS 49.99 R14734 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST PEOPLE'S INSTINCTIVE TRAVELS 69.99 5351106 ABBA GOLD 49.99 19075850371 ABORTED TERRORVISION COLOURED VINYL 49.99 88697383771 AC/DC BLACK ICE 49.99 5107611 AC/DC LET THERE BE ROCK 41.99 5107621 AC/DC POWERAGE 47.99 5107581 ACDC 74 JAIL BREAK 49.99 5107651 ACDC BACK IN BLACK 45 XLLP313 ADELE 19 32.99 XLLP520 ADELE 21 32.99 XLLP740 ADELE 25 29.99 1866310761 ADOLESCENTS THE COMPLETE DEMOS 34.95 LL030LP ADRIAN YOUNGE SOMETHING ABOUT APRIL II 52.8 M27196 AEROSMITH ST 39.99 J12713 AFGHAN WHIGS 1965 49.99 P18761 AFGHAN WHIGS BLACK LOVE 42.99 OP048 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2012-2017 59.99 OP053 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2017-2019 61.99 S80109 AIMEE MANN MENTAL ILLNESS 42.95 7747280 AINTS 5,6,7,8,9 39.99 1.90296E+11 AIR CASANOVA 70 PIC DISC RSD 40 2438488481 AIR VIRGIN SUICIDE 37.99 SPINE799189 AIRBOURNE BREAKIN OUTTA HELL STND EDT 45.95 NW31135-1 AIRBOURNE DIAMOND CUTS THE B SIDES 44.99 FN279LP AK79 40TH ANNIV EDT 63.99 VS001 ALAN BRAUFMAN VALLEY OF SEARCH 47.99 M76741 ALAN PARSONS I