Consultancy Study on the Heritage Conservation Regimes in Other Jurisdictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

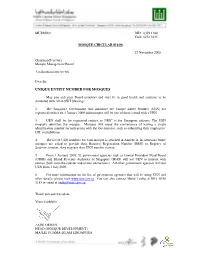

Unique Entity Number for Mosques

MUI/MO/2 DID : 6359 1180 FAX: 6252 3235 MOSQUE CIRCULAR 014/08 27 November 2008 Chairman/Secretary Mosque Management Board Assalamualaikum wr wb Dear Sir UNIQUE ENTITY NUMBER FOR MOSQUES May you and your Board members and staff be in good health and continue to be showered with Allah SWT blessings. 2 The Singapore Government will introduce the Unique Entity Number (UEN) for registered entities on 1 January 2009 and mosques will be one of those issued with a UEN 3 UEN shall be for registered entities as NRIC is for Singapore citizens. The UEN uniquely identifies the mosque. Mosques will enjoy the convenience of having a single identification number for interaction with the Government, such as submitting their employees’ CPF contributions. 4 The list of UEN numbers for each mosque is attached in Annexe A. In situations where mosques are asked to provide their Business Registration Number (BRN) or Registry of Societies number, they may use their UEN number instead. 5 From 1 January 2009, 52 government agencies such as Central Provident Fund Board (CPFB) and Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) will use UEN to interact with entities (both over-the-counter and online interactions). All other government agencies will use UEN from 1 July 2009. 6 For more information on the list of government agencies that will be using UEN and other details, please visit www.uen.gov.sg . You can also contact Muhd Taufiq at DID: 6359 1185 or email at [email protected] . Thank you and wassalam. Yours faithfully ZAINI OSMAN HEAD (MOSQUE DEVELOPMENT) MAJLIS -

Jadual Solat Aidilfitri Bahasa Bahasa Penyampaian Penyampaian No

JADUAL SOLAT AIDILFITRI BAHASA BAHASA PENYAMPAIAN PENYAMPAIAN NO. NAMA & ALAMAT MASJID WAKTU KHUTBAH NO. NAMA & ALAMAT MASJID WAKTU KHUTBAH KELOMPOK MASJID UTARA KELOMPOK MASJID TIMUR LOKASI WAKTU 1 Masjid Abdul Hamid Kg Pasiran, 10 Gentle Rd 8:00 pg Melayu 1 Masjid Al-Ansar, 155 Bedok North Avenue 1 8:00 pg Melayu DAERAH TIMUR 2 Masjid Ahmad Ibrahim, 15 Jln Ulu Seletar 7:45 pg Melayu 2 Masjid Al-Istighfar, 2 Pasir Ris Walk 7:35 pg Melayu 1 Dewan Serba guna Blk 757B, Pasir Ris St 71 8:00 pg 3 Masjid Alkaff Upper Serangoon, 8:00 pg Melayu 3 Masjid Darul Aman, 1 Jalan Eunos 8:30 pg Melayu 2 Kolong Blk 108 & 116, Simei Street 1 8:15 pg 66 Pheng Geck Avenue 9:30 pg Bengali 3 Kolong Blk 286, Tampines St 22 8:15 pg 4 Masjid Al-Istiqamah, 2 Serangoon North Avenue 2 8:00 pg Melayu 4 Masjid Alkaff Kampung Melayu, 8:00 pg Melayu 5 Masjid Al-Muttaqin, 5140 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 6 7:45 pg Melayu 4 Kolong Blk 450, Tampines St 42 8:00 pg 200 Bedok Reservoir Road 8:45 pg Inggeris 5 Dewan Serba guna Blk 498N, Tampines St 45 8:15 pg 5 Masjid Al-Mawaddah, 151 Compassvale Bow 8:00 pg Melayu 6 Masjid An-Nahdhah, No 9A Bishan St 14 8:00 pg Melayu 6 Kolong (Tingkat 2) Blk 827A, Tampines St 81 8:30 pg 6 Masjid Darul Ghufran, 503 Tampines Avenue 5 8:00 pg Melayu 7 Masjid An-Nur, 6 Admiralty Road 7:30 pg Melayu 7 Kolong Blk 898, Tampines St 81 8:15 pg 7 Masjid Haji Mohd Salleh (Geylang), 8:00 pg Melayu 8 Masjid Assyafaah, 1 Admiralty Lane 8:00 pg Melayu 8 Kolong Blk 847, Tampines St 83 8:00 pg 245 Geylang Road 9:00 pg Bengali 9.15 pg Bengali 9 Kolong Blk 924, Tampines -

Download Map and Guide

Bukit Pasoh Telok Ayer Kreta Ayer CHINATOWN A Walking Guide Travel through 14 amazing stops to experience the best of Chinatown in 6 hours. A quick introduction to the neighbourhoods Kreta Ayer Kreta Ayer means “water cart” in Malay. It refers to ox-drawn carts that brought water to the district in the 19th and 20th centuries. The water was drawn from wells at Ann Siang Hill. Back in those days, this area was known for its clusters of teahouses and opera theatres, and the infamous brothels, gambling houses and opium dens that lined the streets. Much of its sordid history has been cleaned up. However, remnants of its vibrant past are still present – especially during festive periods like the Lunar New Year and the Mid-Autumn celebrations. Telok Ayer Meaning “bay water” in Malay, Telok Ayer was at the shoreline where early immigrants disembarked from their long voyages. Designated a Chinese district by Stamford Raffles in 1822, this is the oldest neighbourhood in Chinatown. Covering Ann Siang and Club Street, this richly diverse area is packed with trendy bars and hipster cafés housed in beautifully conserved shophouses. Bukit Pasoh Located on a hill, Bukit Pasoh is lined with award-winning restaurants, boutique hotels, and conserved art deco shophouses. Once upon a time, earthen pots were produced here. Hence, its name – pasoh, which means pot in Malay. The most vibrant street in this area is Keong Saik Road – a former red-light district where gangs and vice once thrived. Today, it’s a hip enclave for stylish hotels, cool bars and great food. -

JADUAL WAKTU SOLAT HARI RAYA EIDULFITRI DI MASJID-MASJID 17 Julai 2015 / 1 Syawal 1436H

JADUAL WAKTU SOLAT HARI RAYA EIDULFITRI DI MASJID-MASJID 17 Julai 2015 / 1 Syawal 1436H NO. NAMA & ALAMAT MASJID WAKTU BAHASA PENYAMPAIAN KHUTBAH Kelompok Masjid Tengah Utara 1 Masjid Abdul Hamid Kg Pasiran, 10 Gentle Rd 8.00 pg Melayu 2 Masjid Al-Muttaqin, 5140 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 6 7.45 pg Melayu 8.45 pg Inggeris Masjid Angullia, 265 Serangoon Road 7.30 pg Tamil 3 8.30 pg Bengali 9.00 pg Urdu 4 Masjid An-Nahdhah, No 9A Bishan St 14 8.00 pg Melayu 5 Masjid Ba'alwie, 2 Lewis Road 8.30 pg Melayu 6 Masjid Haji Mohd Salleh (Geylang), 245 Geylang Road 8.00 pg Melayu & Inggeris 9.00 pg Bengali 7 Masjid Hajjah Fatimah, 4001 Beach Road 8.00 pg Melayu 8 Masjid Hajjah Rahimabi, 76 Kim Keat Road 8.30 pg Melayu 9 Masjid Malabar, 471 Victoria Street 9.00 pg Inggeris, Arab, Malayalam & Urdu 10 Masjid Muhajirin, 275 Braddell Road 8.15 pg Melayu 11 Masjid Omar Salmah, 441B Jalan Mashor 8.15 pg Melayu 12 Masjid Sultan, 3 Muscat Street 8.30 pg Melayu 13 Masjid Tasek Utara, 46 Bristol Road 8.00 pg Melayu Kelompok Masjid Tengah Selatan 1 Masjid Abdul Gafoor, 41 Dunlop Street 7.30 pg Tamil & 8.30 pg 2 Masjid Al-Abrar (Koochoo Pally), 192 Telok Ayer Street 8.30 pg Tamil 3 Masjid Al-Amin, 50 Telok Blangah Way 8.00 pg Melayu 4 Masjid Al-Falah, Cairnhill Place #01-01, Bideford Road 8.15 pg Inggeris 5 Masjid Bencoolen, 51 Bencoolen St, #01-01 8.00 pg Tamil 6 Masjid Haji Muhammad Salleh (Palmer), 37 Palmer Road 8.15 pg Melayu & Inggeris 7 Masjid Jamae Chulia, 218 South Bridge Road 8.30 pg Tamil 8 Masjid Jamae Queenstown, 946 Margaret Drive 8.30 pg Melayu 9 Masjid Jamiyah Ar-Rabitah. -

List of Mosques Reopening Under Phase 1B (Correct As at 5 June 2020)

List of mosques reopening under Phase 1B (correct as at 5 June 2020) From 8 June 2020 Operating Hours Weekends S/No Cluster Mosque Subuh Zohor Asar Maghrib Isyak AM PM & PH 1 Masjid Al-Amin ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 2 Masjid Jamae Chulia ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 3 Masjid Jamek Queenstown ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 9 pm 5:30 am - Open 4 Masjid Mujahidin ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 7 am 5 Masjid Tasek Utara ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 9 pm 6 Masjid Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ (Fridays from 2pm) 7 Masjid Al-Falah ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 9 pm Open 8 Masjid Malabar ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 9 pm Open 9 Masjid Hajjah Fatimah ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 9 pm Closed 10 Masjid Hj Mohd Salleh (Palmer) ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 9 pm Closed 11 Masjid Omar Kampong Melaka ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 9 pm Closed South 12 Masjid Angullia ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 8 pm Closed 13 Masjid Kampong Delta ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 8 pm Closed Saturday 14 Masjid Moulana Mohd Ali ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 8 pm Only 15 Masjid Al-Abrar ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 6 pm Closed 16 Masjid Jamiyah Ar-Rabitah ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 6 pm Closed 17 Masjid Sultan ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 6 pm Closed 18 Masjid Abdul Gafoor 19 Masjid Ba'alwie 20 Masjid Bencoolen CLOSED Masjid Burhani 21 From 8 June 2020 Operating Hours Weekends S/No Cluster Mosque Subuh Zohor Asar Maghrib Isyak AM PM & PH 22 Masjid Ahmad ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 23 Masjid Al-Huda ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 24 Masjid Al-Iman ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 25 Masjid Al-Khair ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 26 Masjid Al-Mukminin ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 27 Masjid Ar-Raudhah ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 5:30 am - 28 Masjid Assyakirin ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 1 pm - 9 pm Open 7 am 29 Masjid Darussalam ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 30 West Masjid Hang Jebat ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 31 Masjid Hasanah ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 32 Masjid Maarof ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ -

1 Annex a List of Mosques Offering 3 Eid Prayers on 31 July 2020

Annex A List of mosques offering 3 Eid prayers on 31 July 2020 (7.30 a.m., 8.30 a.m.and 9.30 a.m.) Mosque Cluster 1. Masjid Abdul Aleem Siddique 2. Masjid Al Abdul Razak 3. Masjid Al-Ansar 4. Masjid Al-Islah 5. Masjid Al-Istighfar (spaces available for Muslimah) 6. Masjid Alkaff Kampung Melayu 7. Masjid Al-Mawaddah 8. Masjid Al-Taqua East 9. Masjid Darul Ghufran 10. Masjid Haji Mohd Salleh (Geylang) 11. Masjid Kampung Siglap 12. Masjid Kassim 13. Masjid Khalid 14. Masjid Khadijah 15. Masjid Mydin 16. Masjid Wak Tanjong 17. Masjid Abdul Hamid (Kg Pasiran) 18. Masjid Ahmad Ibrahim 19. Masjid Al-Istiqamah 20. Masjid Al-Muttaqin 21. Masjid An-Nahdhah 22. Masjid An-Nur 23. Masjid Assyafaah (spaces available for Muslimah) North 24. Masjid Darul Makmur 25. Masjid En-Naeem 26. Masjid Hajjah Rahimabi Kebun Limau 27. Masjid Haji Yusoff 28. Masjid Yusof Ishak 29. Masjid Petempatan Melayu Sembawang 30. Masjid Al-Amin 31. Masjid Hajjah Fatimah South 32. Masjid Jamae Chulia 33. Masjid Mujahidin (spaces available for Muslimah) 34. Masjid Ahmad 35. Masjid Al-Huda 36. Masjid Al-Iman (spaces available for Muslimah) 37. Masjid Al-Khair West 38. Masjid Al-Mukminin 39. Masjid Ar-Raudhah 40. Masjid Assyakirin 1 41. Masjid Darussalam 42. Masjid Hang Jebat 43. Masjid Hasanah 44. Masjid Maarof 45. Masjid Tentera Di Raja List of mosques offering 2 Eid Prayers prayers on 31 July 2020 (7.30 a.m. and 8.30 a.m.) Mosque Cluster 1. Masjid Alkaff (Upper Serangoon) 2. Masjid Muhajirin North 3. -

EARLY PHOTOGRAPHS of SINGAPORE 1841–1918 P

Vol. 15 Issue 03 OCT–DEC 2019 02 / The Five-footway Story 20 / Outwitting the Communists 26 / Hindu Doll Festival 32 / Singapore Before 1867 42 / The First Feature Film 58 / Biodiversity Heritage Library EARLY PHOTOGRAPHS OF SINGAPORE 1841–1918 p. 8 biblioasia VOLUME 15 OCT Welcome to the final issue of BiblioAsia for the year. DEC Do make time to visit the National Library’s latest exhibition, “On Paper: Singapore Before ISSUE 03 2019 Director’s CONTENTS 1867”, which takes place at level 10 of the National Library building until March 2020. We preview several paper-based artefacts – four paintings, two poems in Jawi script, a map and a Russian FEATURES Note travelogue – that feature in the exhibition capturing Singapore’s history from the 17th century to when it became a British Crown Colony on 1 April 1867. Many of the artefacts in the exhibition, The Making of Xin Ke some of which are on loan from overseas institutions, are on public display for the first time. 02 32 42 The first practical method of creating permanent images with a camera was unveiled to the world by Frenchman Louis Daguerre in 1839, so it is no surprise that Europeans dominated the Give Me photography business in 19th-century Singapore. Some of the earliest images of landscapes and people here were taken by the likes of Gaston Dutronquoy, John Thomson, the Sachtler brothers Shelter and G.R. Lambert. Janice Loo charts the rise and fall of Singapore’s first photographic studios. The Five-footway Story The “five-footway” is another inherited tradition from Singapore’s colonial days. -

PERJALANAN SINGAPURA KEBUDAYAAN • KISAH-KISAH MENARIK • MAKANAN HALAL TEMPAT BERIBADAH • Bagi Wisatawan Muslim Panduan PENDAHULUAN

Panduan PERJALANAN SINGAPURA bagi Wisatawan Muslim MAKANAN HALAL • TEMPAT BERIBADAH • KEBUDAYAAN • KISAH-KISAH MENARIK EDISI PERTAMA | 2020 | VERSI BAHASA | 2020 | INDONESIA EDISI PERTAMA PENDAHULUAN Singapura yang ramah bagi wisatawan Muslim P18 LITTLE INDIA Sebanyak 14 persen dari penduduk Singapura adalah Panduan ini memberikan Anda informasi yang pemeluk agama Islam dan tidak heran jika Singapura bermanfaat untuk liburan Anda di Singapura— memiliki banyak kuliner yang dapat dinikmati oleh kota yang menawarkan segala keinginan Anda. MASJID SULTAN P10 KAMPONG GELAM wisatawan Muslim tanpa rasa khawatir. Tempat- Anda juga dapat mengunduh aplikasi MuslimSG P06 ORCHARD ROAD tempat makan tersebut mendapatkan sertifikasi dari dan mengikuti @halalSG di Twitter untuk segala MUIS (Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura). Wisatawan informasi Halal selama berada di Singapura. dapat dengan mudah mengunjungi tempat-tempat makan Halal di seluruh Singapura. Selain itu, masjid dan – Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS) musholla juga banyak terdapat di seluruh Singapura P34 ESPLANADE bagi Anda untuk menunaikan ibadah saat liburan. TIONG BAHRU P22 TIONGMARKET BAHRU P26 CHINATOWN P34 MARINA BAY DAFTAR ISI 05 TIPS 26 CHINATOWN ORCHARD 06 ROAD 30 SENTOSA KAMPONG MARINA BAY & PETA TUJUH KAWASAN 10 GELAM 34 ESPLANADE WISATA DI SINGAPURA Panduan wisata akan tujuh kawasan di Singapura LITTLE RENCANA P30 SENTOSA ini khusus ditulis bagi 18 INDIA 38 PERJALANAN wisatawan Muslim demi kenyamanan Anda selama berada di Singapura. TIONG DAFTAR RESTORAN 22 BAHRU 42 HALAL Tourism Court Panduan ini dibuat dengan masukan dari para penulis ternama 1 Orchard Spring Lane seperti Nur Safiah Alias dan Suffian Hakim, serta CrescentRating, Singapore 247729 sebuah badan yang tidak asing lagi dalam industri wisata Halal. Tel: (65) 6736 6622 stb.gov.sg Catatan: Badan Pariwisata Singapura Penjelasan dapat diperoleh langsung dari setiap pihak ketiga yang atau Singapore Tourism Board (STB) tidak dirujuk dalam publikasi ini. -

The Impact of Being Tamil on Religious Life Among Tamil Muslims in Singapore Torsten Tschacher a Thesis Submitted for the Degree

THE IMPACT OF BEING TAMIL ON RELIGIOUS LIFE AMONG TAMIL MUSLIMS IN SINGAPORE TORSTEN TSCHACHER (M.A, UNIVERSITY OF COLOGNE, GERMANY) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is difficult to enumerate all the individuals and institutions in Singapore, India, and Europe that helped me conduct my research and provided me with information and hospitality. Respondents were enthusiastic and helpful, and I have accumulated many debts in the course of my research. In Singapore, the greatest thanks have to go to all the Tamil Muslims, too numerous to enumerate in detail, who shared their views, opinions and knowledge about Singaporean Tamil Muslim society with me in interviews and conversations. I am also indebted to the members of many Indian Muslim associations who allowed me to observe and study their activities and kept me updated about recent developments. In this regard, special mention has to be made of Mohamed Nasim and K. Sulaiman (Malabar Muslim Juma-ath); A.G. Mohamed Mustapha (Rifayee Thareeq Association of Singapore); Naseer Ghani, A.R. Mashuthoo, M.A. Malike, Raja Mohamed Maiden, Moulana Moulavi M. Mohamed Mohideen Faizi, and Jalaludin Peer Mohamed (Singapore Kadayanallur Muslim League); K.O. Shaik Alaudeen, A.S. Sayed Majunoon, and Mohamed Jaafar (Singapore Tenkasi Muslim Welfare Society); Ebrahim Marican (South Indian Jamiathul Ulama and Tamil Muslim Jama‘at); M. Feroz Khan (Thiruvithancode Muslim Union); K.M. Deen (Thopputhurai Muslim Association (Singapore)); Pakir Maideen and Mohd Kamal (Thuckalay Muslim Association); and Farihullah s/o Abdul Wahab Safiullah (United Indian Muslim Association). -

Annex a Status of Mosque Services on 2 June 2020 1. Mosques to Open

Annex A Status of Mosque Services on 2 June 2020 1. Mosques to open limited spaces for private prayer a. 5 marked private prayer zones for up to five individuals or up to 5 households with up to 5 individuals per household b. Priority for mobile essential workers c. 2 June to 7 June - Mosques to open for daily prayers between 1 p.m. to 6 p.m. d. 8 June - most mosques to be open for five daily prayers 2. Resumption of pre-school services at 15 mosque-based kindergartens (in line with ECDA’s guidelines, to allow young children to continue learning and support parents as they return to work) a. 2 June – K1 and K2 classes to reopen b. 8 June – N1 and N2 classes to reopen 3. Islamic Education and Religious Query Services to continue online 4. Social Development Services a. Financial Assistance to continue b. Check-in with Zakat Beneficiaries to continue via phone, urgent face-to-face sessions may be conducted on a needs basis Annex B: LIST OF MOSQUES FOR SAFE REOPENING Masjid Abdul Aleem Sidique Masjid Darul Makmur Masjid Abdul Hamid Kampung Pasiran Masjid Darussalam Masjid Ahmad Masjid En-Naeem Masjid Ahmad Ibrahim Masjid Haji Mohd Salleh Masjid Al-Abdul Razak Masjid Haji Muhammad Salleh Masjid Al-Abrar Masjid Haji Yusoff Masjid Al-Amin Hajjah Fatimah Masjid Al-Ansar Masjid Hang Jebat Masjid Al-Falah Masjid Hasanah Masjid Al-Firdaus Masjid Hussein Sulaiman Masjid Al-Huda Masjid Jamae Chulia Masjid Al-Iman Masjid Jamek Queenstown Masjid Al-Istighfar Masjid Jamiyah Ar-Rabitah Masjid Al-Istiqamah Masjid Kassim Masjid Al-Islah Masjid Kampong Delta -

Singapore Mosques Korban Committee

SINGAPORE MOSQUES KORBAN COMMITTEE JKMS Secretariat Centre, Singapore Islamic Hub 273 Braddell Road, Singapore 579702 Tel: 63591408 Fax: 62537572 email: [email protected] EMBARGOED TILL 1st SEPT 2017 @ 7.30PM MEDIA STATEMENT 1st Sept 2017 KORBAN 2017 A RESOUNDING SUCCESS The Singapore Mosques Korban Committee (JKMS) is pleased to announce that Korban 2017 has been completed. As scheduled, the Korban rites were conducted at 25 venues across the island. 2. The 25 korban centres had earlier been approved under the requirements of Australia’s Exporter Supply Chain Assurance System (ESCAS)1 regulatory framework. Auditors were also present at all centres to ensure proper handling and slaughtering of livestock. 3. JKMS express its gratitude to Agri–Food and Veterinary Authority (AVA) for helping to ensure that Korban was carried out in accordance with international standards of animal welfare, and to mosque personnel and volunteers who worked tirelessly to ensure smooth operations this year, especially the younger and newer ones. 4. JKMS Chairman Hj Saat Matari says,”We are seeing quite a number of fresh faces who wants to gain deeper understanding and appreciate the symbolic meaning behind korban. During the training sessions, we can see that they’re ready to step up and willing to learn. Together with the seasoned volunteers, we are seeing an incident-free korban operations this year.” 5. JKMS is also grateful for the trust from the community in ensuring that this important ritual and syiar is able to be maintained. 6. For further details, please contact Ibrahim Sawifi at 9685 4714 / [email protected] or Izzairin Swandi at 9112 0950 / [email protected] JAWATANKUASA KORBAN MASJID-MASJID DI SINGAPURA (JKMS) SINGAPORE MOSQUES KORBAN COMMITTEE 1 ESCAS is a regulatory framework implemented by the Australian Government in 2012 to ensure that livestock exported from Australia to different countries are treated in accordance to the World Organisation for Animal Health’s (OIE) internationally accepted animal welfare standards. -

Download Annual Report 2017

SHAPING RELIGIOUS LIFE Harnessing Capabilities • Enhancing Institutions • Strengthening Partnerships ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS Vision, Mission, Strategic Priority .............................................................. 1 President Foreword ................................................................................... 2 Chief Executive Message .......................................................................... 4 Senior Management .................................................................................. 6 The Singaporean Muslim Identity .............................................................. 7 Council Members ...................................................................................... 8 Highlights of 2017 ................................................................................... 10 HARNESSING CAPABILITIES ................................................................ 18 ENHANCING INSTITUTIONS ................................................................ 30 STRENGTHENING PARTNERSHIPS...................................................... 40 List of Special Panels and Committees 2017 .......................................... 66 Muis Visitors ............................................................................................ 70 List of Mosques ....................................................................................... 71 Partnering The Community: Wakaf Disbursement .................................. 74 Partnering The Community: Muis Donations ........................................