Woodchuck EN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornell's Naturalist Outreach Presents: Rodents: Nutty Adaptations For

Cornell’s Naturalist Outreach Presents: Rodents: Nutty Adaptations for Survival By: Ashley Eisenhauer What is a rodent? Rodents are a very diverse, interesting group of animals. They can be found on every continent except for Antarctica. The largest rodent is the Capybara (left picture) from South America, and the smallest—about the size of a quarter—is the pygmy jerboa (right picture), indigenous to Africa. The feature all rodents share are continuously growing, gnawing teeth. This is what causes them to constantly chew on things, because they need to grind their teeth to keep them the proper size and sharpen them. Their other features, such as their vision, hearing, fur, feet, tails, sociality, and survival methods during the winter vary from species to species. Exploring the diversity of rodents is an effective way of demonstrating adaptations in animals. The rodents I will be talking about with students are the eastern gray squirrel, northern flying squirrel, woodchuck/groundhog, eastern chipmunk, and chinchilla. All of these are indigenous to New York, except the chinchilla which is from the Andes Mountains in South America. I will be bringing my pet chinchillas to my presentations to show how certain aspects of chinchillas are different from the rodents that live here in New York because of the climate difference. Some of these differences include larger ears for heat dissipation, thick fur for cold nights, and large herd sociality. Local critters that are often mistaken as rodents are rabbits, which are actually Lagomorphs. This is a common misconception because they also have continuously growing teeth and are constantly chewing on something. -

Vancouver Island Marmot

Vancouver Island Marmot Restricted to the mountains of Vancouver Island, this endangered species is one of the rarest animals in North America. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks move between colonies can have a profound one basket” situation puts the Vancouver impact on the entire population. Island Marmot at considerable risk of Vancouver Island Marmots have disap- extinction. peared from about two-thirds of their his- Why are Vancouver Island torical natural range within the past several What is their status? Marmots at risk? decades and their numbers have declined by urveys of known and potential colony he Vancouver Island Marmot exists about 70 percent in the last 10 years. The sites from 1982 through 1986 resulted in nowhere in the world except Vancouver 1998 population consisted of fewer than 100 counts of up to 235 marmots. Counts Island.Low numbers and extremely local- individuals, making this one of the rarest Srepeated from 1994 through 1998 turned Tized distribution put them at risk. Human mammals in North America. Most of the up only 71 to 103 animals in exactly the same activities, bad weather, predators, disease or current population is concentrated on fewer areas. At least 12 colony extinctions have sheer bad luck could drive this unique animal than a dozen mountains in a small area of occurred since the 1980s. Only two new to extinction in the blink of an eye. about 150 square kilometres on southern colonies were identified during the 1990s. For thousands of years, Vancouver Island Vancouver Island. Estimating marmot numbers is an Marmots have been restricted to small Causes of marmot disappearances imprecise science since counts undoubtedly patches of suitable subalpine meadow from northern Vancouver Island remain underestimate true abundance. -

Groundhog Day 2020: for the First Time in History, Punxsutawney Phil Predicts Second Consecutive Early Spring

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 2, 2020 Groundhog Day 2020: For the First Time in History, Punxsutawney Phil Predicts Second Consecutive Early Spring Punxsutawney, PA – This morning, Pennsylvania’s own world-famous groundhog Punxsutawney Phil once again predicted an early spring after he did not see his shadow, a prediction so rare that it has only happened 20 times in the 134-year history of Groundhog Day and never two years in a row. Residents of Punxsutawney and visitors from across the nation gathered to see Phil make his highly-anticipated weather prognostication, during Pennsylvania’s unique Groundhog Day celebration. “Groundhog Day is a beloved Pennsylvania tradition that has been embraced wholeheartedly by communities across the country,” said Gov. Tom Wolf. “We are honored Phil has called our commonwealth his home for more than 100 years and look forward to continuing to share his prediction with visitors, residents, and the millions watching from their homes.” The event now attracts up to 30,000 visitors to Punxsutawney, Jefferson County, located about 80 miles northeast of Pittsburgh. Phil has predicted six more weeks of winter weather 104 times while forecasting an early spring 20 times. The story of the holiday tradition declares that if the groundhog emerges early on the morning of February 2 and sees his shadow, we will have six more weeks of winter weather. Should he not see his shadow, we will have an early spring. The annual event began in 1886, when a spirited group of groundhog hunters dubbed themselves "The Punxsutawney Groundhog Club” and proclaimed Punxsutawney Phil to be the one and only weather prognosticating groundhog. -

2019 Issue I from Our Founding Board Member Wildlife in Need Center WOW

I L D LI F E th W Anniversary I Y R E N A E R S N T E N E E D C 2019 Wildlife Tracks 2019 Issue I From our Founding Board Member Wildlife In Need Center WOW... twenty five, XXV, I thought it would be a way to give W349 S1480 S. Waterville Road 25 Years !!! No matter how you say it something back to the outdoors which Oconomowoc, WI 53066 or write it when it comes to WINC my family has enjoyed forever. I don’t 262-965-3090 it’s not just a number. feel it’s overstated to say the work www.helpingwildlife.org done at the Center adds to the quality When Kim asked me as a founding of life within and beyond the board member to write an article for communities it serves. the Newsletter to reflect on our first 25 years my brain was immediately One reason I feel the Center is here flooded with more thoughts than you after 25 years is because the Center can imagine. To begin with, this is has never lost sight of its core What’s Inside my first article ever for the mission. This focus has Newsletter. I’ll make a allowed the Center to From our Founding commitment to all of you excel in the areas of Board Member Page 1 now, if this gets past the patient care and editors, to write an article education. Education The Sandhill Crane And Wildlife every 25 years. not only with respect In Need Center’s Connection Page 2 to the many presen- Mange Red Fox Page 3 Writing this is difficult tations given each year because space doesn’t allow but also through the for a full accounting of your thousands of calls the A Summary Glance at Patient Statistics Page 4 accomplishments over these Center receives regarding 25 years. -

Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 ON THE COVER Hoary Marmot (Marmota caligata) Photograph courtesy of Roger Christophersen, North Cascades National Park Complex Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 Roger G. Christophersen National Park Service North Cascades National Park Complex 810 State Route 20 Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284 June 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Wildlife Spotting Along the Thames

WILDLIFE SPOTTING ALONG THE THAMES Wildlife along the Thames is plentiful, making it a great location for birding. Bald Eagles and Osprey are regularly seen nesting and feeding along the river. Many larger birds utilize the Thames for habitat and feeding, including Red Tailed Hawks, Red Shoulder Hawks, Kestrels, King Fishers, Turkey Vultures, Wild Turkeys, Canada Geese, Blue Herons, Mallard Ducks, Black and Wood Ducks. Several species of owl have also been recorded in, such as the Barred Owl, Barn Owl, Great Horned Owl and even the Snowy Owl. Large migratory birds such as Cormorants, Tundra Swans, Great Egret, Common Merganser and Common Loon move through the watershed during spring and fall. The Thames watershed also contains one of Canada’s most diverse fish communities. Over 90 fish species have been recorded (more than half of Ontario’s fish species). Sport fishing is popular throughout the watershed, with popular species being: Rock Bass, Smallmouth Bass, Largemouth Bass, Walleye, Yellow Perch, White Perch, Crappie, Sunfish, Northern Pike, Grass Pickerel, Muskellunge, Longnose Gar, Salmon, Brown Trout, Brook Trout, Rainbow Trout, Channel Catfish, Barbot and Redhorse Sucker. Many mammals utilize the Thames River and the surrounding environment. White-tailed Deer, Muskrat, Beaver, Rabbit, Weasel, Groundhog, Chipmunk, Possum, Grey Squirrel, Flying Squirrel, Little Brown Bats, Raccoon, Coyote, Red Fox and - although very rare - Cougar and Black Bear have been recorded. Reptiles and amphibians in the watershed include Newts and Sinks, Garter Snake, Ribbon Snake, Foxsnake, Rat Snake, Spotted Turtle, Map Turtle, Painted Turtle, Snapping Turtle and Spiny Softshell Turtle. Some of the wildlife species found along the Thames are endangered making it vital to respect and not disrupt their sensitive habitat areas. -

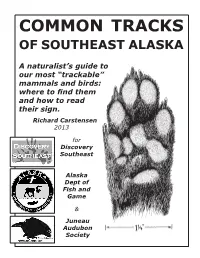

Common Tracks of Southeast Alaska

COMMON TRACKS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA A naturalist’s guide to our most “trackable” mammals and birds: where to find them and how to read their sign. Richard Carstensen 2013 for Discovery Southeast Alaska Dept of Fish and Game & Juneau Audubon Society TRACKING HABITATS muddy beaches stream yards & trails mudflat banks buildings keen’s mouse* red-backed vole* long-tailed vole* red squirrel beaver porcupine shrews* snowshoe hare* black-tailed deer domestic dog house cat black bear short-t. weasel* mink marten* river otter * Light-footed. Tracks usually found only on snow. ISBN: 978-0-9853474-0-6# 2013 text & illustrations © Discovery Southeast Printed by Alaska Litho Juneau, Alaska 1 CONTENTS DISCOVERY SOUTHEAST ........................................................... 2 ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME ............................... 3 PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION ............................................ 5 TRACKING BASICS: LINGO, GAITS ......................................... 10 SCIENTIFIC NAMES ................................................................ 16 MAMMAL TRACK DESCRIPTIONS ............................................ 18 BIRD TRACK DESCRIPTIONS .................................................. 35 AMPHIBIANS .......................................................................... 40 OTHER MAMMALS ................................................................... 41 OTHER BIRDS ......................................................................... 45 RECOMMENDED FIELD -

The Overlookoverlook

TheThe OverlookOverlook www.FriendsOfIroquoisNWR.org Winter 2020 Banner Photo (2019 First-Place Wildlife) by William Major Oak Orchard Christmas Bird Count 2019 On December 27, 2019, 21 volunteers participated in the 52nd annual Oak Orchard Swamp Christmas Bird Count. The National Audubon Society, in collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sponsor Christmas Bird Counts annually throughout the country and beyond in the Americas. Each count consists of a tally of all birds seen within a fifteen-mile diameter circle on one day that falls within a 15-day period at the end of December and the beginning of January. Audubon Christmas Counts have been taking place for 119 years and provide valuable information on the range expansion or narrowing of wintering bird populations. The center for the Oak Orchard count is the point at which the Genesee-Orleans County line crosses Route 63. The 15-mile diameter circle includes the Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge, Oak Orchard and Tonawanda State Wildlife Management Areas, the Tonawanda Native American Reservation, the Townships of Alabama and Shelby, the villages of Indian Falls, Medina and Wolcottsville and portions of Middleport and Oakfield. Count hours were warm and mild, with a low of 39F and high of 57F. both above the average daily temperature for the date of 34F. Both morning and afternoon were essentially precipitation free. Our observers were afield in fourteen parties from 6:30 AM until 5:50 PM, and in 322.5 total hours covered 35 miles on foot and 504 miles by car! One observer counted birds at home feeders. -

The Delightful Book That Answers the Questions

The delightful book that answers the questions... • Why is my home being invaded by bats? And how can I make them find somewhere else to live? • Why is the great horned owl one of the few predators to regularly dine on skunk? I What are the three reasons you may have weasels around your house but never see them? I What event in the middle of winter will bring possums out in full force? • Wliat common Michigan animal has been dubbed "the most feared mammal on the North American continent"? I Why would we be wise to shun the cute little mouse and welcome a big black snake? I Why should you be very careful where you stack the firewood? NATURE FROM YOUR BACK DOOR MSU is an Affirmative-Action Equal HOpportunity Institution. Cooperative Extension Service programs are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, sex or handicap. I Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work in agriculture and home economics, acts of May 8, and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Gail L. Imig, director, Cooperative Extension Service, Michigan State University, E. Lansing, Ml 48824. Produced by Outreach Communications MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY Extension Bulletin E-2323 ISBN 1-56525-000-1 ©1991 Cooperative Extension Service, Michigan State University Illustrations ©1991 Brenda Shear 7VATURE ^-^ from YOUR BACK DOOR/ By Glenn R. Dudderar Extension Wildlife Specialist Michigan State University Leslie Johnson Outreach Communications Michigan State University ?f Illustrations by Brenda Shear FIRST EDITION — AUTUMN 1991 NATURE FROM YOUR BACK DOOR INTRODUCTION WHEN I CAME TO MICHIGAN IN THE MID-1970S, I WAS SURPRISED at the prevailing attitude that nature and wildlife were things to see and enjoy if you went "up north". -

Montana Owl Workshop

MONTANA OWL WORKSHOP APRIL 25–30, 2021 LEADER: DENVER HOLT LIST COMPILED BY: DENVER HOLT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM MONTANA OWL WORKSHOP APRIL 25–30, 2021 By Denver Holt The winter of 2021 was relatively mild, with only one big storm in October and one cold snap in February. In fact, Great Horned Owls began nesting at the onset of this cold snap. Our female at the ORI field station began laying eggs and incubating. For almost a week the temperature dropped from about 20 degrees F to 10, then 0, then minus 10, minus 15, and eventually minus 28 degrees below zero. Meanwhile, the male roosted nearby and provided his mate with food while she incubated eggs. Eventually, the pair raised three young to fledging. Our group was able to see the entire family. By late February to early March, an influx of Short-eared Owls occurred. I had never seen anything like it. Hundreds of Short-eared Owls arrived in the valley. Flocks of 15, 20, 35, 50, and 70 were regularly reported by ranchers, birders, photographers, and others. And, in one evening I counted 90, of which 73 were roosting on fence posts and counted at one time. By mid-to-late March, however, except for Great Horned Owls, other owl species numbers dropped significantly. We found only one individual Long-eared Owl and zero nests in our Missoula study site. It’s been many, many years since we have not found a nest in Missoula. -

Groundhog Day

National Climatic Data Center Formerly the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC)… more about NCEI » Home Climate Information Data Access Customer Support Contact About Search Home > Customer Support > Education Resources > Groundhog Day Browser Support Issues Groundhog Day Online Store Every February 2, thousands gather at Gobbler’s Knob Check Order Status in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, to await the spring Certication of Data forecast from a special groundhog. Known as Tools Punxsutawney Phil, this groundhog will emerge from Partnerships his simulated tree trunk home and look for his shadow, which will help him make his much- World Data Centers anticipated forecast. According to legend, if Phil sees Education Resources his shadow the United States is in store for six more Groundhog Day weeks of winter weather. But, if Phil doesn’t see his shadow, the country should expect warmer Archiving your Data temperatures and the arrival of an early spring. History of Groundhog Day Groundhog Day originates from an ancient celebration of the midway point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox—the day right in the middle of astronomical winter. According to superstition, sunny skies that day signify a stormy and cold second half of winter while cloudy skies indicate the arrival of warm weather. The trail of Phil’s history leads back to Clymer H. Freas, city editor of the Punxsutawney Spirit newspaper. Inspired by a group of local groundhog hunters—whom he would dub the Punxsutawney Groundhog Club— Freas declared Phil as America’s ocial forecasting groundhog in 1887. As he continued to embellish the groundhog's story year after year, other newspapers picked it up, and soon everyone looked to Punxsutawney Phil for the prediction of when spring would return to the country. -

Groundhog Day Is Celebrated on February 2Nd and It Is the Day When People Look to the Groundhog to Predict the Weather for the Next Six Weeks

GROUDHOG DAY READ ABOUT THIS TRAD ITION A N D TELL YOUR PARTNER IS A S M U C H DETAIL AS POSSIBLE Source: https://www.ducksters.com/ Useful Vocabulary: burrow/ˈbʌr.əʊ/ hole or tunnel dug by a small animal, especially a rabbit, as a dwelling, especially to live in www.cristinacabal.com Groundhog Day is celebrated on February 2nd and it is the day when people look to the groundhog to predict the weather for the next six weeks. Folklore says that if the sun is shining when the ground hog comes out of his burrow, then the groundhog will go back into its burrow and we will have winter for six more weeks. However, if it is cloudy, then spring will come early that year. This is a tradition in the United States. There are a number of celebrations throughout the United States. The largest celebration takes place in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania where the famous groundhog Punxsutawney Phil has predicted the weather each year since 1886. Large crowds of well over 10,000 people gather here to see Phil come out of his burrow at around 7:30am. The origins of Groundhog Day can be traced to German settlers in Pennsylvania. These settlers celebrated February 2nd as Candlemas Day. On this day if the sun came out then there would be six more weeks of wintry weather. At some point people began to look to the groundhog to make this prediction. The earliest reference to the groundhog is in an 1841 journal entry. In 1886 the Punxsutawney newspaper declared February 2nd as Groundhog Day and named the local groundhog as Punxsutawney Phil.