Evsjv‡`K Cwi‡Ek ‡Buiqvk© (†Eb)-Gi Msmöv‡Gi 20 Eqi (1998-2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See Resource File

Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh (Global Partnership in Attainment of the SDGs) General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh September 2019 Prospects and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh Published by: General Economics Division (GED) Bangladesh Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Website: www.plancomm.gov.bd First Published: September 2019 Editor: Dr. Shamsul Alam, Member (Senior Secretary), GED Printed By: Inteshar Printers 217/A, Fokirapool, Motijheel, Dhaka. Cell: +88 01921-440444 Copies Printed: 1000 ii Bangladesh Planning Commission Message I would like to congratulate General Economics Division (GED) of the Bangladesh Planning Commission for conducting an insightful study on “Prospect and Opportunities of International Cooperation in Attaining SDG Targets in Bangladesh” – an analytical study in the field international cooperation for attaining SDGs in Bangladesh. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda is an ambitious development agenda, which can’t be achieved in isolation. It aims to end poverty, hunger and inequality; act on climate change and the environment; care for people and the planet; and build strong institutions and partnerships. The underlying core slogan is ‘No One Is Left Behind!’ So, attaining the SDGs would be a challenging task, particularly mobilizing adequate resources for their implementation in a timely manner. Apart from the common challenges such as inadequate data, inadequate tax collection, inadequate FDI, insufficient private investment, there are other unique and emerging challenges that stem from the challenges of graduation from LDC by 2024 which would limit preferential benefits that Bangladesh have been enjoying so far. -

An Alternative Report to the Fifth State Party Periodic Report to UNCRC

An Alternative Report to the Fifth State Party Periodic Report to UNCRC State Party: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Contact Information: Submitted By: Child Rights Advocacy Save the Children in Coalition in Bangladesh Bangladesh House-82, Road- 19A, Block-E, Banani Dhaka, Bangladesh Tel: +88-02-9861690, Fax: +88-02-9886372 Web: www.savethechildren.net 30th October 2014 Table of Contents PART I: GENERAL OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1 Background and Context ............................................................................................................................. 1 Objective of the Alternative Report ............................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Organization of the Alternative Report ...................................................................................................... 1 PART II: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE UNCRC IN BANGLADESH ........................................................ 2 3.3 Rights of children with disabilities and children belonging to minorities........................................ 8 4.3 Freedom of expression and right to seek, receive and impart information ................................. 11 4.4 Freedom of association and peaceful assembly............................................................................ -

QBRI Leads Neurological Research Initiatives

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Bengaluru FC take on Air Force Club of INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2, 16 COMMENT 14, 15 North Sea oil fl ood REGION 3 BUSINESS 1 – 12 Iraq in AFC Cup looms as Opec 17,911.27 9,955.99 44.12 ARAB WORLD 3 CLASSIFIED 7, 8 -19.40 -117.07 -0.54 INTERNATIONAL 4 – 13 SPORTS 1 – 8 plans output cuts fi nal today -0.11% -1.16% -1.21% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 SATURDAY Vol. XXXVII No. 10263 November 5, 2016 Safar 5, 1438 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Festival showcases Chinese culture In brief QBRI leads neurological QATAR | Phone call Congratulations to al-Hariri HE the Prime Minister and Minister of Interior Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser research bin Khalifa al-Thani yesterday held a telephone conversation with Saad al-Hariri, congratulating the latter for becoming the prime minister of Lebanon. HE Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser stressed during the initiatives call that the State of Qatar would continue its support to Lebanon and QBRI is pioneering an remain committed to the latter’s epidemiological study to find the security and stability. He wished the Zhejiang’s leading performers entertaining the crowd with traditional music and dances yesterday at the Chinese Festival 2016, prevalence rate of autism in Qatar Lebanese people further progress which concludes today at the Museum of Islamic Art Park. The four-day event, which features a variety of Chinese cultural and prosperity. Lebanon’s newly- shows and activities, art and crafts exhibitions, food, and workshops, is a key part of the Qatar China Year of Culture, which By Joseph Varghese elected President Michel Aoun on ends in December. -

The Power of Using the Right to Information Act in Bangladesh

World Bank Group The Power of Using the Right to Information Act in Bangladesh: Experiences from the Ground World Bank Institute 1 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………... Pg. 3 Story #1: Rezia Khatun used the RTI Act to get a Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) card…………………………………………………………………………………………... Pg. 5 Story #2: Shamima Akter uses the RTI Act to help vulnerable women to access government programs in her village………………………………………………………………………… Pg. 6 Story #3: Jobeda Begum uses information to increase the beneficiaries on a government program………………………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 7 Story #4: Rafiqul Islam demands information to bring transparency to the distribution of grains. Pg. 8 Story #5: RTI Act helps in implementing minimum wage in shrimp processing………………... Pg. 9 Story #6: The use of RTI for environmental advocacy against illegal building………………….. Pg. 11 Story #7: Mosharaf Hossain uses the RTI Act to ensure that his online complaint for migrant workers is heard……………………………………………………………………………… Pg. 13 Story #8: Information Commission helps Mosharef Hossain Majhi to access information on agriculture issues…………………………………………………….……………. Pg. 15 Story #9: By using the RTI Act, poor women receive access to maternal health vouchers…….. Pg. 17 Story #10: Landless committees use the RTI Act to gain access to land records……………… Pg. 19 Story #11: RTI Act helps improve the lives of fishermen……………………………………... Pg. 21 Story #12: By using the RTI Act, Mohammad gets access to the Agriculture Input Assistance Card…………………………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 23 Story #13: RTI helps to place names on a list of beneficiaries in government program………. Pg. 25 Story #14: Rabidas community utilizes RTI for getting Old Age Pension in Saidpur, Nilphamari. Pg. 26 Story #15: RTI Act enables Munna Das to get information from the youth development officer. -

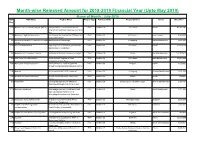

Upto May 2019) Name of Month : July-2018 NGO NGO Name Project Name Project Type Released Date Project District Sector Allocation Reg

Month-wise Released Amount for 2018-2019 Financial Year (Upto May 2019) Name of Month : July-2018 NGO NGO Name Project Name Project Type Released Date Project District Sector Allocation Reg. 2473 Medicins Sans Frontieres-Belgium (MSFB) Ukhiya the Host Community Outreach FD-6 2018-Jul-26 Cox's Bazar Health 83,062,387 Program and Outbreak Response Coxs bazar Dist 55 Madaripur Legal Aid Association Lets Cleanup the Country Day 2018 and Lets FD-6 2018-Jul-25 All Districts, Environment 6,000,000 Build Green Schools 135 Mohamuni Bidhaba-O-Anath Shishu Kalyan Maintenance of Orphanage FD-6 2018-Jul-22 Chittagong, Social Development 3,032,500 Kendra 2266 Nutrition International Operating Cost of Alleviating Micronutient FD-6 2018-Jul-01 All Districts, Health 45,604,296 Malnutrition in Bangladesh 665 Medecins Sans Frontieres - France Re-Launch of Mission Coordination Project FD-6 2018-Jul-28 Dhaka, Social Development 123,787,691 476 NGO Forum For Public Health WASH Support Program for Host FD-6 2018-Jul-28 Cox's Bazar Local Government 37,867,093 Community in Coxs Bazar 2997 Mafizuddin Nazeda Foundation Rural Community Health Programme FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Dinajpur, Health 1,100,000 through Mofizuddin Mazed Medical Centre 1181 Mamata HER Project-MAMATA(HER Finance) FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Chittagong, Women Development 5,691,289 1982 Mosabbir Memorial foundation Strenthening of Mosabbir Cancer Care FD-6 2018-Jul-09 Dhaka, Health 834,827 Centre 943 Naripokkho Claiming the Right to Safe Menstrual FD-6 2018-Jul-29 Dhaka, Barisal, Patuakhali, Bogra, Women Development -

The Millennium Development Goals

The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Progress Report 2009 has been benefited from the financial and technical assistance of the United Nations System in Bangladesh. The Millennium Development Goals The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Design & Published by General Economics Division Planning Commission Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Copies printed: 2500 Printed by Scheme Service Genesis (Pvt.) Ltd., Dhaka, Bangladesh The Millennium Development Goals Bangladesh Progress Report 2009 Message Air Vice Marshal (Retd.) A. K. Khandker The Millennium Development Goals Minister Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh I am happy to learn that the General Economics Division (GED) of the Bangladesh Planning Commission has prepared the `Millennium Development Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2009’ taking inputs from relevant ministries and related stakeholders along with the technical assistance from the UN Systems. As the coming Sixty-fifth session of the United Nations General Assembly, inter alia, will review the latest achievements of the MDGs, the report will be supportive to do the same for Bangladesh The Government of Bangladesh is committed to achieve the MDGs within the given timeframe and accordingly prepared an action plan. The National Strategy for Accelerated Poverty Reduction (NSAPR-1), the Medium Term Budgetary Framework (MTBF) and the Annual Development Programs (ADPs) have also been tuned towards achieving the MDGs. -

Acknowledgment to Reviewers of Applied Sciences in 2020

Editorial Acknowledgment to Reviewers of Applied Sciences in 2020 Applied Sciences Editorial Office MDPI AG, St. Alban-Anlage 66, 4052 Basel, Switzerland Peer review is the driving force of journal development, and reviewers are gatekeepers who ensure that Applied Sciences maintains its standards for the high quality of its pub- lished papers. Thanks to the cooperation of our reviewers, in 2020, the median time to first decision was 15 days and the median time to publication was 35 days. The editors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the following reviewers for their precious time and dedication, regardless of whether the papers were finally published: Aamir, Muhammad Abdeljaber, Osama Aarniovuori, Lassi Abdelkader, Amr Aasa, Ulrika Abdelkefi, Abdessattar Aase, Reyes Abdellatef, Mohammed Abad, Begoña Abdellatif, Mohamed Abah, Obinna Abdelmaksoud, Ahmed Abainia, Kheireddine Abdelrahman, Mohamed Abalasei, Aurelia Beatrice Abdelrazec, Ahmed H. M. Abanteriba, Sylvester Abdelsalam, Mahmoud Abarca-Sos, Alberto Abdelsalam, Sara I. Abaspur Kazerouni, Iman Abdelwahed, Sameh Abate, Giada Abdi, Ghasem Abate, Lorenzo Abdo, Ahmad Abatzoglou, Nicolas Abdo, Peter Citation: Applied Sciences Editorial Abawajy, Jemal Abdul-Aziz, Ali Office. Acknowledgment to Abaza, Osama A. Abdulhammed, Razan Reviewers of Applied Sciences in 2020. Abbas, Farhat Abdulkhaleq, Ahmed Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1108. https:// Abbasi Layegh, Mahmood abdullah, Abu Yousuf Md doi.org/10.3390/app11031108 Abbasi, Hamid Abdullah, Oday Ibraheem Abbasi, Ubaid Abdullah, Tariq Published: 26 January 2021 Abbasnia, Arash Abdulmajeed, Wael Abbaspour, Aiyoub Abdur, Rahim Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neu- Abbatangelo, Marco Abed, Eyad H. tral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institu- Abbes, Boussad Abedi, Reza tional affiliations. -

Country Youth Prof Ile - Bangladesh

Country Youth Prof ile - Bangladesh Country Youth Prof ile BANGLADESH Women and Youth Empowerment Division Resilience and Social Development Department February 201 1 1. Socio-economic Profile 1.1. The People’s Republic of Bangladesh is located on the North-eastern part of South Asia, with a projected pop- ulation of 167,414.566 in 20191. The country experienced a steady economic growth rate between 2010-2017 with its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) averaging over 6% annually reaching a peak of 7.3% in 2017, the highest in the country’s history2. Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in reducing poverty. The population living below the national poverty line dropped from 31.5% in 2010 to 24.3% in 20163. The proportion of the employed living below the $1.90 purchasing power parity (PPP) a day dropped from 44.2% in 1991 to14.8% in 2016/20174. In parallel, the country achieved a lower middle-income status in 2015 and qualified for graduation from a Least Developing Coun- try in March 2018 and is on track for graduation in 20245. 1.2 Bangladesh’s position on the United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) 2017 Human Development Index (HDI) moved up three positions from its 2016 rank of 139th to 136th out of 189 countries6. However, Bangladesh’s HDI of 0.608 is below the average of 0.631 and 0.645 for the medium human development category and South Asian countries respectively7. 1.3. The official characterization of youth in Bangladesh refers to persons between ages 18-35. However, the youth data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) is based on the 15-29-years age range. -

Sustainability Report 2014

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2014 Concept & Design by Forethought PR Limited I www.forethoughtpr.com This is Grameenphone Grameenphone, part of the Telenor Group, is the leading telecommunications service provider in Bangladesh. Since its inception in 1997, Grameenphone has built the largest cellular network in the country, covering nearly 99 percent of the country's population. With its brand promise, to enable customers to “Go beyond”, Grameenphone seeks to help customers get the full benefit of mobile data and voice services and provide Internet For All. Before Grameenphone’s inception, the phone was for a selected urbanized few. The cell phone was a luxury: a flouting accessory for the select elite. The mass could not contemplate mobile telephony as being part of their lives. Due to its long term commitment to Bangladesh, the company swiftly expanded its network around the country, providing affordable communication solutions to all. Grameenphone is listed on the Dhaka Stock Exchange. It is also among the top contributors to the government exchequer. The company has also created employment for a large number of people both directly and indirectly. The telecom industry has the power to transform society. Our influence represents a I am pleased to present the Grameenphone Sustainability Report for 2014. This Report great opportunity but also a significant responsibility. That’s why sustainability is at the provides an overview of Grameenphone’s actions and results in terms of social and core of Telenor Group’s approach to doing business in all its markets. I’m pleased to see environmental performance. that Grameenphone is now publishing its sustainability report. -

Institutionalizing Local Level Poverty Monitoring System (LLPMS)

Institutionalizing Local Level Poverty Monitoring System (LLPMS) Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) Kotbari, Comilla Bangladesh July 2013 0 | P a g e I Project Overview 1 Title of the Institutionalizing Local Level Poverty Monitoring System (LLPMS) Project 2 Project Proponent a Name of Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) Institution b Name of Head of Mr. Md. Mashiur Rahman Institution c Mailing Address Kotbari, Comilla, Bangladesh d Telephone and Tel. +88 081 60600 Fax Numbers Fax. +88 081 68406 e E-mail Address [email protected] f Web-site www.bard.gov.bd g Brief Profile of Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) was established the Proponent in 1959 basically as a training institute. In course of time, however, it Institution has combined training with research and pilot experimentation. The unified approach of training, research and pilot experimentation to solve problems of rural areas has given special significance to the activities of the Academy. Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) as a national institute of rural development in Bangladesh is mandated to perform specific functions which are: 1) provide training to government officials and others concerned with rural development; 2) conduct research in rural development and allied fields; 3) test and experiment on concepts and theories of development; 4) provide advisory and consultative service to the Government and other agencies; 5) guide and supervise students, national and foreign, in their dissertation works; 6) arrange and conduct national and international seminars, conferences and workshops, and 7) help policy planners in the field of rural development. In order to perform these functions, it has 09 divisions, of which four are service divisions and 05 are academic divisions. -

Profile of Md. Sabur Khan Founder & Chairman, Daffodil International

Profile of Md. Sabur Khan Founder & Chairman, Daffodil International University Chairman, Daffodil Family Director, World IT & Services Alliance (WITSA) Chairman, Global Trade Committee, WITSA Honorary Fellowship, Said Business School, Oxford Guest Professor, Changchun University of Finance and Economics (CUFE), China Visiting Professor, Universitas Ubudiyah Indonesia Honorary Professor, Adam University Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan Honorary Professor, Issyk-Kul State University, Karakol, Kyrgyzstan Honorary D. Litt, Techno India University, India Honorary Doctorate, Ala-Too International University, Bishkek,Kyrgyzstan Honorary Doctorate, Naryn State University, Kyrgyzstan Former President, Dhaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DCCI) Former President, Bangladesh Computer Samity (BCS) Author, Art of Living; Handbook of Entrepreneurship Development; Uddokta Unnayan Nirdeshika; A Journey towards Entrepreneurship; Uddokta Unnayan O Nirdeshona Page 1 of 71 Page of Contents Profile of Md. Sabur Khan Page of Contents Introduction 03 A Successful Businessman 05 Interview & discussion with news media 06 Positions hold as the Daffodil Family Spearhead 07 Social Status (Present) 09 Social Status (Past) 09 Membership 10 Scholarships/Training 11 Significant Awards 12 Government Delegation (International) 16 Business Delegation (International) 17 Distinguished Social Contributions 25 Contributions 27 Development Chronology of Daffodil Family 30 Entrepreneurial Initiatives 38 Remarkable Achievements 49 Miscellaneous 53 Meet With World Leaders 54 Conferences, Seminars & Fairs 55 Country Visited 56 Business Success/Contribution 56 Activities as DCCI President 57 Some Quotes 70 Last but not the least 70 Useful links 71 Page 2 of 71 Page of Contents Introduction A serial entrepreneur and self-made businessman, Mr. Md. Sabur Khan started his business career in 1990 by Daffodil Computers Ltd., 1st public listed IT company. -

Combatting Black Money, Corruption and Money Laundering in Bangladesh: the Ogd Must Bark to Keep Predators Away' S M

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2018 'Captured by Evils' - Combatting Black Money, Corruption and Money Laundering in Bangladesh: The ogD Must Bark to Keep Predators Away' S M. Solaiman University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details S. M. Solaiman, ''Captured by Evils' - Combatting Black Money, Corruption and Money Laundering in Bangladesh: The oD g Must Bark to Keep Predators Away'' (2018) 21 (3) Journal of Money Laundering Control 264-289. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] 'Captured by Evils' - Combatting Black Money, Corruption and Money Laundering in Bangladesh: The ogD Must Bark to Keep Predators Away' Abstract Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate that the recurrent amnesties to black money holders (BMHs) in Bangladesh have not benefited the national economy, rather have increased corruption and money laundering, and that offering further opportunity to whiten back money as recommended by the Anti- Corruption Commission of Bangladesh will do more harm than good. Design/methodology/approach: This research relies on both primary and secondary materials adopting an archival analysis of the existing literature. Findings: The am jor findings include the following: the recurrent amnesties to BMHs have damaging impacts on corruption and money laundering in Bangladesh; the Anti-Corruption Commission of Bangladesh's recommendation to provide further opportunity to legalise black money is flawed, ill thought-out and misjudgement of the futility of the amnesties offered to date; and the black money problem could be better addressed through using educational, preventive and punitive measures that have been specifically formulated in this paper.