The Map of Gauteng: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List & Contacts of Project Developers

LIST & CONTACTS OF PROJECT DEVELOPERS PROJECT NAME PROJECT OWNER ADDRESS CONTACT PERSON CONTACT No. E-MAIL PROJECT TYPE PROJECT LOCATION Kuyasa low cost urban housing Tel: 012 349 1901 7200 Fax: energy project City of Cape Town Private Bag X 4, Parow, 7499 Mr Osman Asmal 2716 976 2650 Cell: [email protected] Energy Efficiency Cape Town, Western Cape P O Box 35630, Menlo Park, Hydro power electricity Bethlehem Hydro NuPlanet BV 0102 Mr Anton Lewis Tel: 012 349 1901 [email protected] generation Bethlehem, Free State Province 65 Parklane,PO Box 782178, Tel: 031 910 1344 Cell: 082 Fuel switching from coal Rosslyn brewery fuel switch project South African Brewery Sandton, Mr Tony Cole 924 2176 Fax: 086 687 1124 [email protected] to natural gas Rosslyn, Gauteng P.O.Box 210367, Durban North, Tel: 031 560 3419 Fax: 031 560 Fuel switching from coal Lawley fuel switch project Corobrik 4016 Mr Dirk Meyer 3483 [email protected] to natural gas Johannesburg, Gauteng P O Box 829, Rant-en-Dal 1751, Tel: 021 883 3474 Fax: 021 425 PetroSA biogas to energy project Methcap (pty)Ltd South Africa Adv Johan van der Berg 5055 [email protected] Cogeneration Mossel Bay, Western Cape 101 Devon House 20, Georgian Crescent Hampton Office Park, Tel: 011 514 0441 Cell:083 258 Emfuleni power project EcoElectrica (pty) Ltd Bryanston Ms Vanessa Gounden 3249 [email protected] Cogeneration Vanderbjilpark, Gauteng Durban Landfilling gas to electricity project - Marrianhill and La Mercy 17 Electron Road, Springfield, Tel: 27 31 2631 371 Fax: 27 31 Methane recovery and landfills Ethekwini Municipality PO Box 1038 Dr. -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

The Attrition of Rape Cases Through the Criminal Justice System in Gauteng

Lisa Vetten, Rachel Jewkes, Romi Sigsworth, Nicola Christofides, Lizle Loots, Olivia Dunseith Tracking Justice: The Attrition of Rape Cases through the Criminal Justice System in Gauteng July 2008 Tshwaranang Legal Advocacy Centre to End Violence Against Women (TLAC) Tel: +27 (11) 403-8230/4267, Fax: +27 (11) 403-4275 www.tlac.org.za South African Medical Research Council (MRC) Gender & Health Research Unit Tel: +27 (12) 339-8526, Fax +27 (12) 339-8582 www.mrc.ac.za Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Tel: +27 (11) 403-5650, Fax: +27 (11) 339-6785 www.csvr.org.za To be cited as: Vetten, L., Jewkes, R., Sigsworth, R., Christofides, N., Loots, L. and Dunseith, O. 2008. Tracking Justice: The Attrition of Rape Cases Through the Criminal Justice System in Gauteng. Johannesburg: Tshwaranang Legal Advocacy Centre, the South African Medical Research Council and the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. Design and Illustration: Ellen Papciak-Rose (Soweto Spaza cc), www.ellenpapciakrose.com Lisa Vetten, TLAC Rachel Jewkes, MRC Romi Sigsworth, CSVR Nicola Christofides, MRC Lizle Loots, MRC Olivia Dunseith, TLAC figures and tables Figures 1 Rape in South Africa per province ������������������������������������������������������� 12 2 Stages in the investigation and prosecution of a rape complaint �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 3 Distribution of victims, by age ��������������������������������������������������������������� 29 4 -

Going Beyond

Going Beyond THE BIDVEST GROUP LIMITED DIRECTORY APRIL 2018 Index and Directory DirectoryAddingTitle value Name across Telephone Location the national economy Directory 2017 The Bidvest Group Limited Bidvest directory Title Name Telephone Location BIDVEST CORPORATE Bidvest Corporate Services Group chief executive Lindsay Ralphs +27 (11) 772 8700 Johannesburg Bidvest House, 18 Crescent Drive, Chief financial officer Mark Steyn Melrose Arch Executive director Gillian McMahon PO Box 87274, Houghton, 2041 Executive director Mpumi Madisa www.bidvest.com Group company secretarial Ilze Roux Group accounting Paul Roberts Group financial manager Lorinda Petzer Group internal audit Lauren Berrington Group taxation Dharam Naidoo Group retirement funds Lesley Jurgensen +27 (10) 730 0822 Johannesburg Group Treasurer Neil Taylor Corporate finance executive Phathu Tshivhengwa Corporate affairs executive Ilze Roux Business development executive Ravi Govender Financial manager Priscilla da Rocha Business relationship manager Amanda Davidson Commercial executive Akona Ngcuka Events and marketing manager Julie Alexander Bidvest Properties Bidvest House, 18 Crescent Drive, Chief financial officer Ferdi Smit +27 (11) 772 8786 Melrose Arch, 2196 Operational director Warren Kretzmar +27 (11) 772 8725 PO Box 87274, Houghton, 2041 Legal director Colleen Krige +27 (11) 772 8729 Fax: +27 (11) 772 8970 Bidvest Procurement Managing director Derek Kinnear +27 (11) 243 2040 Johannesburg Ground Floor, 158 Jan Smuts Avenue, Financial manager Ilze Rossouw Rosebank, 2196 Operations -

Daniel Francois Meyer, North-West University, South Africa [email protected]

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE STUDIES Vol 10, No 1, 2018 ISSN: 1309-8055 (Online) THE DEVELOPMENT AND APPLICATION OF A REGIONAL AND LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENT Daniel Francois Meyer, North-West University, South Africa [email protected] ─Abstract ─ ─Abstract ─ Globally, local economic development (LED) is recognised as a strategic process that assists with the acceleration of economic development in local regions, in both developed and in developing countries. Economic development practitioners have a need for user-friendly assessment instruments and tools to analyse and compare economic development in regions. The aim of the study was therefore to develop and apply an instrument to assess the economic development potential of a region since such a comprehensive strategic and practical instrument does not exist. Various types of regions, from national to local, could be assessed and compared using the instrument. The development potential (DP) of a region has been formulated as the aggregate of all local resources (R) multiplied by the aggregate of local capacity (C); therefore DP = R x C. Extensive research has lead to the identification of variables contributing to the extent of the local resources and capacity. The methodology included the identification of variables representing capacity and resources and the allocation of values for each variable through a quantitative survey method which included 380 local business people. The instrument was tested in a developing region in South Africa known as the “Vaal-Triangle” region, which includes the municipal areas of Emfuleni, Metsimaholo and Midvaal. In testing and applying the instrument in the study region, it was found that all three areas had low economic development indexes of below 30 (where the maximum is 100). -

Going Beyond

Going Beyond THE BIDVEST GROUP LIMITED DIRECTORY 2017 Index and Directory DirectoryAddingTitle valueName acrossTelephone Location the national economy Directory 2017 The Bidvest Group Limited Bidvest directory Title Name Telephone Location BIDVEST CORPORATE Bidvest Corporate Services Group chief executive Lindsay Ralphs +27 (11) 772 8700 Johannesburg Bidvest House, 18 Crescent Drive, Chief financial officer Peter Meijer Melrose Arch Executive director Gillian McMahon PO Box 87274, Houghton, 2041 Executive director Mpumi Madisa www.bidvest.com Group company secretarial Ilze Roux Group accounting Paul Roberts Group financial manager Lorinda Petzer Group internal audit Lauren Berrington Group taxation Dharam Naidoo Group retirement funds Lesley Jurgensen +27 (10) 730 0822 Johannesburg Group Treasurer Neil Taylor Corporate finance executive Phathu Tshivhengwa Corporate affairs executive Ilze Roux Business development executive Ravi Govender Financial manager Priscilla da Rocha Business relationship manager Amanda Davidson Commercial executive Akona Ngcuka Bidvest Properties Bidvest House, 18 Crescent Drive, Chief financial officer Ferdi Smit +27 (11) 772 8786 Melrose Arch, 2196 Operational director Warren Kretzmar +27 (11) 772 8725 PO Box 87274, Houghton, 2041 Legal director Colleen Krige +27 (11) 772 8729 Fax: +27 (11) 772 8970 Bidvest Procurement Managing director Derek Kinnear +27 (11) 243 2040 Johannesburg Ground Floor, 158 Jan Smuts Avenue, Financial manager Ilze Rossouw Rosebank, 2196 Operations Samira Ramjathan PO Box 1429, Parklands, -

Map & Directions: Regional Head Office Johannesburg

Johannesburg Map & Directions: Regional Head Office Johannesburg Directions from Johannesburg Directions from OR Tambo PHYSICAL ADDRESS: CBD (Newtown) International Airport Yokogawa SA (Pty) Ltd Block C, Cresta Junction Distance: 12.8Km Distance: 48.3Km Corner Beyers Naude Drive and Approximate time: 23 minutes Approximate time: 39 minutes Judges Avenue Cresta Head west on Jeppe St towards Henry Get on to the R24 from To Parking Road Johannesburg, 2194 Nxumalo Street. Continue onto Mahlathini and Exit 46. Keep right at the fork to Street and turn right onto Malherbe Street continue on Exit 46, follow the signs for POSTAL ADDRESS: then turn left onto Lilian Ngoyi Street. Take R24/Johannesburg. Continue on the R24 Yokogawa SA (Pty) Ltd a slight right onto Burghersdorp Street and until it merges with the N12. Continue until PostNet Suite #222 a slight left onto Carr Street. Continue onto exit 113 and take that exit to get onto the Private Bag X1 Subway Street. Turn right onto Seventeenth N3 South/N12 toward M2/Kimberley/ Northcliff, 2115 Street then turn left onto Solomon Street. Germiston/Durban. Keep right at the fork Continue onto Annet Road. Take a slight and follow the signs for N3 S: -26.12737 E: 27.97000 right to stay on Annet Road and continue North/N1/Pretoria and merge onto N3 onto Barry Hertzog Avenue. Turn left onto Eastern Bypass/N1. Continue for 18km. Judith Road after the Barry Hertzog bends. Get into the left lane to take the M5/ Continue on Judith road to the T-junction Beyers Naude Drive exit towards and turn right onto Beyers Naude Drive Honeydew/Northcliff. -

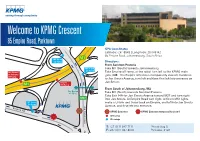

Welcome to KPMG Crescent

Jan Smuts Ave St Andrews M1 Off Ramp Winchester Rd Jan Smuts Off Ramp Welcome to KPMGM27 Crescent M1 North On Ramp De Villiers Graaff Motorway (M1) 85 Empire Road, Parktown St Andrews Rd Albany Rd GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.18548 | Longitude: 28.045142 85 Empire Road, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 B M1 North On Ramp Directions: From Sandton/Pretoria M1 South Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg On Ramp Jan Smuts / Take Empire off ramp, at the robot turn left to the KPMG main St Andrews gate. (NB – the Empire entrance is temporarily closed). Continue Off Ramp to Jan Smuts Avenue, turn left and then first left into entrance on Empire Jan Smuts. M1 Off Ramp From South of JohannesburgWellington Rd /M2 Sky Bridge 4th Floor Take M1 (North) towards Sandton/Pretoria Take Exit 14A for Jan Smuts Avenue toward M27 and turn right M27 into Jan Smuts. At Empire Road turn right, at first traffic lights M1 South make a U-turn and travel back on Empire, and left into Jan Smuts On Ramp M17 Jan Smuts Ave Avenue, and first left into entrance. Empire Rd KPMG Entrance KPMG Entrance temporarily closed Off ramp On ramp T: +27 (0)11 647 7111 Private Bag 9, Jan Jan Smuts Ave F: +27 (0)11 647 8000 Parkview, 2122 E m p ire Rd Welcome to KPMG Wanooka Place St Andrews Rd, Parktown NORTH GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.182416 | Longitude: 28.03816 St Andrews Rd, Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 St Andrews Off Ramp Jan Smuts Ave Directions: Winchester Rd From Sandton/Pretoria Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg Take St Andrews off ramp, at the robot drive straight to the KPMG Jan Smuts main gate. -

The Cholera Outbreak

The Cholera Outbreak: A 2000-2002 case study of the source of the outbreak in the Madlebe Tribal Authority areas, uThungulu Region, KwaZulu-Natal rdsn Edward Cottle The Rural Development Services Network (RDSN) Private Bag X67 Braamfontein 2017 Tel: (011) 403 7324 www.rdsn.org.za Hameda Deedat International Labour and Research Information Group (ILRIG) P.O. Box 1213 Woodstock 7915 Tel: (021) 447 6375 www.aidc.org.za/ilrig Edited by Dudley Moloi Sub-edited by Nicolas Dieltiens Funders: Municipal Services Project SOUTH AFRICAN MUNICIPAL WORKERS’ UNION Acknowledgements A special word of thanks to: Fieldworkers Dudu Khumalo and Sikhumbuso Khanyile from SAMWU KZN, for their help with the community interviews. And to our referees: Dr. David Hemson (Human Science Research Council) Dr. David Sanders (Public Health Programme, University of the Western Cape) Sue Tilley (Social Consultant) Stephen Greenberg (Social Consultant) Contents Executive summary 1 Section 1: Introduction 7 1.1 Objectives of the study 9 Section 2: Methodology 10 2.1 Research methods 10 2.1.1 Transepts 10 2.1.2 In-depth Interviews 11 2.1.3 Interviews in Ngwelezane 11 2.1.4 Interviews in the rural areas 12 2.1.5 Interviews with municipal officials 12 2.2 Limitations of the research 13 Section 3: The Policy Context 14 Section 4: The Geographic Context 16 4.1 A description of the area under Investigation 16 4.1.1 Introduction 16 4.1.2 Brief History 16 4.1.3 Demographic information 17 4.1.4 Economic Expansion 18 4.1.5 Climate & Disease 20 4.1.6 Water & Sanitation 20 4.2 Post-apartheid -

Positioning of the Vaal Triangle in a New South Africa

POSITIONING OF THE VAAL TRIANGLE IN A NEW SOUTH AFRICA Dr D J Bos Department of Town and Regional Planning PU for CHE Manuscript accepted September 1994 1 INTRODUCTION local circumstances. Suggestions and will not dominate other regions concerning the Vaal Triangle, made politically. The process of regional The underlying motivation for the provision for, inter alia: demarcation is, however, as important subdivision of national states into as the final product. Provision was smaller geographic areas, each consist • Sasolburg to be excluded from made to involve the leading parties ing of its own government with spe development Region H, to form from the start by holding regional cific responsibilities, lies in the wishes part of Development region C conventions to determine whether of the inhabitants to make their own (Orange Free State). groups (i) wish to be part of a particu decisions concerning certain matters lar region or not; (ii) need to manage which affect their daily living. This • Development region H to be di common interests joindy; and (iii) approach is based on the phenomenon vided into various sub-regions. wish to handle domestic concerns that countries often consist of disting autonomously. uishable units based on the following • The Vaal Triangle to be excluded factors: climatic and physical aspects from Region H and included in and in addition socio-economic com- Development region C (Orange 1.2 Points of departure munality. Free State). At the time the study was conducted it During the fore election period, a • The Vaal Triangle and the Wit was necessary to make certain decentralized unitary state was being watersrand to form one region and assumptions due to the fact that the considered for South Africa with its the Midrand/Pretoria area, another. -

Architecture

audible architecture • an exploration of the threshold in the public realm as an interactive space • • HM Oosthuizen, s26082340 © University of Pretoria Acknowledgements All thanks to God, without whom I would not have been able to complete this project. Thanks also to my family and friends who supported me through the year. 2 © University of Pretoria audible architecture • an exploration of the threshold in the public realm as an interactive space • HM Oosthuizen Study Leader: Gary White Course Co-ordinators: Jacques Laubscher , Arthur Barker Submitted in fulfi llment of part of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Architecture (Professional) in the Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment and Information Technology, the University of Pretoria. Pretoria, South Africa 2012 © University of Pretoria 3 0.• Acknowledgements_p2 • Table of Contents_p4 • Introduction • 1.01_Project Overview_p8 • 1.02_Primary Objective_p10 • 1.03_Clients_p11 • 1.• 1.04 _Design Approach_p12 • 1.05_Research Methodology_p14 • Current Condition • 2.01_Location_p20 • 2.02_Historical Context_p22 • 2.03_Settlement Edges_p24 • • 2.04 _Access_p26 • 2.05_Activity & Primary Route_p28 • 2.06_Fragmentation_p30 • • 2.07_Existing Frameworks _p32 • 2.• 2.08_Olievenhoutbosch Ministerial Housing Estate Framework_p34 • • 2.09_Current Situation_p37 • 2.10_S.W.O.T. Analysis_p38 • 2.11_Conclusion_p39 • Framework • 3.01_Precinct Intervention_p44 • 3.02_Framework Intent_p46 • • 3.03_Framework Layout_p48 • 3.04 _Spatial Framework: Existing Condition_p50 • • 3.05_Spatial Framework: -

![SIDA Gauteng 2011[2].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9301/sida-gauteng-2011-2-pdf-599301.webp)

SIDA Gauteng 2011[2].Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Letter from Ria Schoeman PhD 4 Abbreviations and Acronyms 4 Helpline and Hotlines in South Africa MUNICIPALITIES 5 City of Johannesburg 29 City of Tshwane 45 Ekurhuleni 61 Metsweding 64 Sedibeng 72 West Rand 1 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ARV: Antiretroviral OVC: Orphans and Vulnerable Children PMTCT Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission STI: Sexually transmitted infection HELPLINE AND HOTLINES IN SOUTH AFRICA Abortion Helpline 080 117 785 Aid for AIDS Helpline 0860 100 646 Alcoholics Anonymous 0861 HELPAA (0861 435 722) Ambulance (Private) 082 911 Ambulance (Public) 10177 Cell phone Emergency Number 112 Child Victims of Sexual, Emotional 0800 035 553 and Physical Abuse Helpline Childline 0800 055 555 Crime Stop 0860 010 111 Department of Education Helpline 0800 202 933 Department of Health Helpline 0800 005 133 Department of Home Affairs Hotline 0800 601 190 Department of Social Development 0800 121 314 Substance Abuse Helpline Emergency Contraception Hotline 0800 246 432 Gay and Lesbian Network Helpline 0860 333 331 HIV Medicines Helpline 0800 212 506 HIV-911 Referral Centre 0860 HIV 911 (0860 448 911) Human Rights Advice Line 0860 120 120 Lifeline Southern Africa 0861 322 322 Legal Aid South Africa Advice Line 0800 204 473 loveLife Sexual Health Line 0800 121 900 (thetha junction) Marie Stopes Clinic Toll Free Number 0800 117 785 mothers2mothers 0800 668 4377 MRI Criticare Emergency Service 0800 111 990 National AIDS Helpline 0800 012 322 National HIV Health Care Workers Hotline 0800 212 506 National Youth Information