Dealing with Cubism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEL AVIV PANTONE 425U Gris PANTONE 653C Bleu Bleu PANTONE 653 C

ART MODERNE ET CONTEMPORAIN TRIPLEX PARIS - NEW YORK TEL AVIV Bleu PANTONE 653 C Gris PANTONE 425 U Bleu PANTONE 653 C Gris PANTONE 425 U ART MODERNE et CONTEMPORAIN Ecole de Paris Tableaux, dessins et sculptures Le Mardi 19 Juin 2012 à 19h. 5, Avenue d’Eylau 75116 Paris Expositions privées: Lundi 18 juin de 10 h. à 18h. Mardi 19 juin de 10h. à 15h. 5, Avenue d’ Eylau 75116 Paris Expert pour les tableaux: Cécile RITZENTHALER Tel: +33 (0) 6 85 07 00 36 [email protected] Assistée d’Alix PIGNON-HERIARD Tel: +33 (0) 1 47 27 76 72 Fax: 33 (0) 1 47 27 70 89 [email protected] EXPERTISES SUR RDV ESTIMATIONS CONDITIONS REPORTS ORDRES D’ACHAt RESERVATION DE PLACES Catalogue en ligne sur notre site www.millon-associes.com בס’’ד MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY FINE ART NEW YORK : Tuesday, June 19, 2012 1 pm TEL AV IV : Tuesday, 19 June 2012 20:00 PARIS : Mardi, 19 Juin 2012 19h AUCTION MATSART USA 444 W. 55th St. New York, NY 10019 PREVIEW IN NEW YORK 444 W. 55th St. New York, NY. 10019 tel. +1-347-705-9820 Thursday June 14 6-8 pm opening reception Friday June 15 11 am – 5 pm Saturday June 16 closed Sunday June 17 11 am – 5 pm Monday June 18 11 am – 5 pm Other times by appointment: 1 347 705 9820 PREVIEW AND SALES ROOM IN TEL AVIV 15 Frishman St., Tel Aviv +972-2-6251049 Thursday June 14 6-10 pm opening reception Friday June 15 11 am – 3 pm Saturday June 16 closed Sunday June 17 11 am – 6 pm Monday June 18 11 am – 6 pm tuesday June 19 (auction day) 11 am – 2 pm Bleu PREVIEW ANDPANTONE 653 C SALES ROOM IN PARIS Gris 5, avenuePANTONE d’Eylau, 425 U 75016 Paris Monday 18 June 10 am – 6 pm tuesday 19 June 10 am – 3 pm live Auction 123 will be held simultaneously bid worldwide and selected items will be exhibited www.artonline.com at each of three locations as noted in the catalog. -

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions As of August 1, 2002 Note to the Reader The works of art illustrated in color in the preceding pages represent a selection of the objects in the exhibition Gifts in Honor of the 125th Anniversary of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Checklist that follows includes all of the Museum’s anniversary acquisitions, not just those in the exhibition. The Checklist has been organized by geography (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America) and within each continent by broad category (Costume and Textiles; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints, Drawings, and Photographs; Sculpture). Within each category, works of art are listed chronologically. An asterisk indicates that an object is illustrated in black and white in the Checklist. Page references are to color plates. For gifts of a collection numbering more than forty objects, an overview of the contents of the collection is provided in lieu of information about each individual object. Certain gifts have been the subject of separate exhibitions with their own catalogues. In such instances, the reader is referred to the section For Further Reading. Africa | Sculpture AFRICA ASIA Floral, Leaf, Crane, and Turtle Roundels Vests (2) Colonel Stephen McCormick’s continued generosity to Plain-weave cotton with tsutsugaki (rice-paste Plain-weave cotton with cotton sashiko (darning the Museum in the form of the gift of an impressive 1 Sculpture Costume and Textiles resist), 57 x 54 inches (120.7 x 115.6 cm) stitches) (2000-113-17), 30 ⁄4 x 24 inches (77.5 x group of forty-one Korean and Chinese objects is espe- 2000-113-9 61 cm); plain-weave shifu (cotton warp and paper cially remarkable for the variety and depth it offers as a 1 1. -

ACCADEMIA FINE ART Monaco Auction

ACCADEMIA FINE ART Monaco Auction Par le Ministère de Organisation & Direction générale Me M.-Th. Escaut-Marquet, Huissier à Monaco Joël GIRARDI Vente aux enchères publiques à l’Hôtel de Paris, Monte-Carlo Gestion et organisation générale Salons Bosio - Beaumarchais François Xavier VANDERBORGHT Vente menée par Serge HUTRY Directeur du département Bijoux Fethia EL MAY Diplômée de l’Institut National de Gemmologie Relation publique Samedi 22 Juin 2013 à 16h30 Alessandra TESTA Exposition publique Photographe Jeudi 20 et Vendredi 21 Juin de 10h à 20h Marcel LOLI Samedi 22 Juin de 10h à 14h Retrait des lots à l’Hôtel de Paris Dimanche 23 Juin 2013 Accademia Fine Art ouvre l’ère des enchères virtuelles : grace à Artfact Live, vous avez la possibilité de suivre en direct la vente et d’enchérir en direct sur internet pendant nos ventes. 2 3 ACCADEMIA FINE ART Monaco Auction Par le Ministère de Organisation & Direction générale Me M.-Th. Escaut-Marquet, Huissier à Monaco Joël GIRARDI Vente aux enchères publiques à l’Hôtel de Paris, Monte-Carlo Gestion et organisation générale Salons Bosio - Beaumarchais François Xavier VANDERBORGHT Vente menée par Serge HUTRY Directeur du département Bijoux Fethia EL MAY Diplômée de l’Institut National de Gemmologie Relation publique Samedi 22 Juin 2013 à 16h30 Alessandra TESTA Exposition publique Photographe Jeudi 20 et Vendredi 21 Juin de 10h à 20h Marcel LOLI Samedi 22 Juin de 10h à 14h Retrait des lots à l’Hôtel de Paris Dimanche 23 Juin 2013 Accademia Fine Art ouvre l’ère des enchères virtuelles : grace à Artfact Live, vous avez la possibilité de suivre en direct la vente et d’enchérir en direct sur internet pendant nos ventes. -

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection Paul Cézanne Mont Sainte-Victoire, c. 1904–06 (La Montagne Sainte-Victoire) oil on canvas Collection of the Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE WINTER 2015 Contents Program Information and Goals .................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Exhibition Cézanne and the Modern ........................................................................... 4 Preparing Your Students: Nudes in Art ....................................................................................................... 5 Artists’ Background ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Modern European Art Movements .............................................................................................................. 8 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. About the Artists ....................................................................................................................... 9 Artist Information Sheet ........................................................................................................ 10 Modern European Art Movements Fact Sheet .................................................................... 12 Student Worksheet ............................................................................................................... -

Jean METZINGER (Nantes 1883 - Paris 1956)

Jean METZINGER (Nantes 1883 - Paris 1956) The Yellow Feather (La Plume Jaune) Pencil on paper. Signed and dated Metzinger 12 in pencil at the lower left. 315 x 231 mm. (12 3/8 x 9 1/8 in.) The present sheet is closely related to Jean Metzinger’s large painting The Yellow Feather, a seminal Cubist canvas of 1912, which is today in an American private collection. The painting was one of twelve works by Metzinger included in the Cubist exhibition at the Salon de La Section d’Or in 1912. One of the few paintings of this period to be dated by the artist, The Yellow Feather is regarded by scholars as a touchstone of Metzinger’s early Cubist period. Drawn with a precise yet sensitive handling of fine graphite on paper, the drawing repeats the multifaceted, fragmented planes of the face in the painting, along with the single staring eye, drawn as a simple curlicue. The Yellow Feather was one of several Cubist paintings depicting women in fashionable clothes, and with ostrich feathers in their hats, which were painted by Metzinger in 1912 and 1913. Provenance: alerie Hopkins-Thomas, Paris Private collection, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, until 2011. Literature: Jean-Paul Monery, Les chemins de cubisme, exhibition catalogue, Saint-Tropez, 1999, illustrated pp.134-135; Anisabelle Berès and Michel Arveiller, Au temps des Cubistes, 1910-1920, exhibition catalogue, Paris, 2006, pp.428-429, no.180. Artist description: Trained in the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Nantes, Jean Metzinger sent three paintings to the Salon des Indépendants in 1903 and, having sold them, soon thereafter settled in Paris. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

Recording of Marcel Duchamp’S Armory Show

Recording of Marcel Duchamp’s Armory Show Lecture, 1963 [The following is the transcript of the talk Marcel Duchamp (Fig. 1A, 1B)gave on February 17th, 1963, on the occasion of the opening ceremonies of the 50th anniversary retrospective of the 1913 Armory Show (Munson-Williams-Procter Institute, Utica, NY, February 17th – March 31st; Armory of the 69th Regiment, NY, April 6th – 28th) Mr. Richard N. Miller was in attendance that day taping the Utica lecture. Its total length is 48:08. The following transcription by Taylor M. Stapleton of this previously unknown recording is published inTout-Fait for the first time.] click to enlarge Figure 1A Marcel Duchamp in Utica at the opening of “The Armory Show-50th Anniversary Exhibition, 2/17/1963″ Figure 1B Marcel Duchamp at the entrance of the th50 anniversary exhibition of the Armory Show, NY, April 1963, Photo: Michel Sanouillet Announcer: I present to you Marcel Duchamp. (Applause) Marcel Duchamp: (aside) It’s OK now, is it? Is it done? Can you hear me? Can you hear me now? Yes, I think so. I’ll have to put my glasses on. As you all know (feedback noise). My God. (laughter.)As you all know, the Armory Show was opened on February 17th, 1913, fifty years ago, to the day (Fig. 2A, 2B). As a result of this event, it is rewarding to realize that, in these last fifty years, the United States has collected, in its private collections and its museums, probably the greatest examples of modern art in the world today. It would be interesting, like in all revivals, to compare the reactions of the two different audiences, fifty years apart. -

Les Ornements De La Femme : L'éventail, L'ombrelle, Le Gant, Le Manchon (Ed

Les ornements de la femme : l'éventail, l'ombrelle, le gant, le manchon (Ed. complète et définitive) / par Octave Uzanne Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France Uzanne, Octave (1851-1931). Auteur du texte. Les ornements de la femme : l'éventail, l'ombrelle, le gant, le manchon (Ed. complète et définitive) / par Octave Uzanne. 1892. 1/ Les contenus accessibles sur le site Gallica sont pour la plupart des reproductions numériques d'oeuvres tombées dans le domaine public provenant des collections de la BnF. Leur réutilisation s'inscrit dans le cadre de la loi n°78-753 du 17 juillet 1978 : - La réutilisation non commerciale de ces contenus ou dans le cadre d’une publication académique ou scientifique est libre et gratuite dans le respect de la législation en vigueur et notamment du maintien de la mention de source des contenus telle que précisée ci-après : « Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France » ou « Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF ». - La réutilisation commerciale de ces contenus est payante et fait l'objet d'une licence. Est entendue par réutilisation commerciale la revente de contenus sous forme de produits élaborés ou de fourniture de service ou toute autre réutilisation des contenus générant directement des revenus : publication vendue (à l’exception des ouvrages académiques ou scientifiques), une exposition, une production audiovisuelle, un service ou un produit payant, un support à vocation promotionnelle etc. CLIQUER ICI POUR ACCÉDER AUX TARIFS ET À LA LICENCE 2/ Les contenus de Gallica sont la propriété de la BnF au sens de l'article L.2112-1 du code général de la propriété des personnes publiques. -

Librairie Le Galet

1 Librairie le galet FLORENCE FROGER 01 45 27 43 52 06 79 60 18 56 [email protected] DECEMBRE 2016 LITTERATURE - SCIENCES HUMAINES - BEAUX-ARTS Vente uniquement par correspondance Adresse postale : 18, square Alboni 75016 PARIS Conditions générales de vente : Les ouvrages sont complets et en bon état, sauf indications contraires. Nos prix sont nets. Les envois se font en colissimo : le port est à la charge du destinataire. RCS : Paris A 478 866 676 Mme Florence Froger IBAN : FR76 1751 5900 0008 0052 5035 256 BIC : CEPA FR PP 751 2 1 JORN (Asger). AFFICHES DE MAI 1968 : Brisez le cadre qi etouf limage / Aid os etudiants quil puise etudier e aprandre en libert / Vive la révolution pasioné de lintelligence créative / Pas de puissance dimagination sans images puisante. Paris, Galerie Jeanne Bucher. Collection complète des 4 affiches lithographiées en couleurs à 1000 exemplaires par Clot, Bramsen et Georges, et signées dans la pierre par Jorn. Ces affiches étaient destinées à couvrir les murs de la capitale. Parfait état. 1500 € 3 2 [AEROSTATION] TRUCHET (Jean- 6 [ANTI-FRANQUISME] VAZQUEZ Marc). L’AEROSTAT DIRIGEABLE. Une DE SOLA (Andrès). ALELUYAS DE LA vieille idée moderne… COLERA CONTRA LAS BASES Lagnieu, La Plume du temps, 2006. In-4, YANQUIS. broché, couverture illustrée, 119 pages. E.O. Nombreuses illustrations. 20 € Madrid, Supplément au n° 7-8 de Grand Ecart, 1962. Un feuillet A4 3 ALECHINSKY (Pierre), REINHOUD imprimé au recto, plié et TING. SOLO DE SCULPTURE ET DE en 4. Charge DIVERTISSEMENT arrangé pour peinture antifranquiste dénonçant la collaboration à quatre mains. militaire hispano-américaine. -

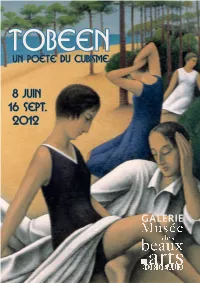

TOBEEN Un Poète Du Cubisme

TOBEEN Un poète du cubisme 8 juin 16 sept. 2012 GALERIE TOBEEN Un poète du cubisme Galerie des Beaux-Arts qui, sous l’impulsion de Picabia, déferle 8 juin – 16 septembre 2012 rue de La Boétie, Metzinger, Juan Gris, Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp, Marcoussis, L’œuvre de Félix-Elie Bonnet dit Tobeen Picabia, Fernand Léger, André Lhote ou (Bordeaux 1880 – Saint-Valery-sur- encore Jacques Villon et Alexandra Exter. Somme, 1938) est celle d’un peintre Son œuvre la plus en vue est Les pétri de régionalisme qui enfourche les Pelotaris, déjà présentée au Salon des préceptes des avant-gardes. Indépendants de 1912 et acquise par le D’origine bordelaise, né en 1880, critique d’art Théodore Duret. Quant au il fait partie du cercle du collectionneur critique du Mercure de France, Gustave et mécène Gabriel Frizeau. Il gardera Kahn, il juge le peintre « compréhensif, des liens d’amitié avec certains de ces robuste, sculptural, dans ses Pelotaris ». intellectuels et artistes entourant l’esthète Autre œuvre remarquable, Le bassin bordelais, comme le critique, tôt disparu, dans le parc de 1913, acquise par Olivier Hourcade et surtout André Lhote Gabriel Frizeau et donnée au musée par avec qui il partage très vite un grand intérêt pour le cubisme. Il s’établit à Paris en 1907 et fréquente les artistes regroupés à Montparnasse, à la Ruche, où il trouve un premier atelier. Cette même année, Picasso devait peindre Les demoiselles d’Avignon et sonner le coup d’envoi du cubisme. Il est aussi un proche du cercle de Puteaux, côtoyant Jacques Villon, Metzinger, Gleizes et prêche, comme eux, pour un art dont le « sujet devenait le métier » (Jacques Villon). -

Modigliani's Recipe: Sex, Drugs and Long, Long Necks

The New York Times, August 3, 2003 Modigliani's Recipe: Sex, Drugs and Long, Long Necks By PETER PLAGENS VINCENT VAN GOGH had a 10-year working life that can hardly be called a "career," and yet he's just about the biggest draw ever in museum exhibitions, at least per square inch of canvas covered. When the 1998 "Van Gogh's van Goghs" exhibition entered the home stretch of its run at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, officials had to keep the place open 24 hours a day on the last weekend to accommodate the crowds. Amedeo Modigliani O.K., that's van Gogh. But since June 26, visitors have been streaming into the same museum at the rate of more than 1,400 a day (which a spokesperson calls "astounding" for them) to see the work of a different painter with an equally brief working life. The attraction, which originated at the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo (where the museum had to turn away visitors during the last two weeks) and then stopped at the Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth, is an exhibition called "Modigliani and the Artists of Montparnasse." (It runs through Sept. 28.) Although the show includes healthy doses of Chagall, Soutine and Rivera (among others), the benighted Amedeo Modigliani (1884- 1920) is the real draw. What is it about this artist, who painted deceptively simple, semi-abstracted, sloe-eyed women over and over again, that pleases the public so much? It could be at least partly the biography. Modigliani was born an outsider — his parents were Sephardic Jews in Livorno, Italy — and grew up sickly and tubercular. -

The Museum of Modern Art 11 West 53 Street, New York 19, N

LOCAL ORANGE THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 11 WEST 53 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. TELEPHONE CIRCLE 5-8900 5lOl|05 - 22 FOR WEDNESDAY RELEASE EXHIBITION OP LIFE WORK OF MODIGLIANI, ITALIAN PAINTER AND SCULPTOR, TO GO ON VIEW Fifty-two oils, 7 sculptures and h£ drawings, watercolors and pastels by the well-known Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani (l88lj.-1920) will occupy the third floor galleries of the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, from April 11 through June 10, Organized in collaboration with The Cleveland Museum of Art, where it has just concluded its showing,, the exhibition has been brought together from collections in Paris and Milan, England and Brazil, and many parts of this country. Among the foreign loans is a large group of early works never exhibited before outside of France, The exhibition was organized by the Depart ment of Painting and Sculpture and installed by Margaret Miller, Associate Curator of the Department, The catalog contains an appreciative essay on the artist by James thrall Soby, the well-known art writer and expert on modern Italian art; lj2 plates, 2 in color; a check-list and bibliography. Biographical Notes: Modigliani was born in Leghorn, Italy, on July 12, I88I4., the youngest of k children of a banker of Jewish origin. He died in Paris at the age of only 35• Following a sickly childhood and an interrupted schooling, he developed tuberculosis at the age of l6 and was taken by his mother to an art school in Rome. In 1906 he went to Paris, where his work was at first influenced by the style of the 1890a, He was soon to come under the spell of Picasso and Ce'zanne.