Intimacy, Difficulty, and Distance in Gwendolyn Brooks’S “Two Dedications”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

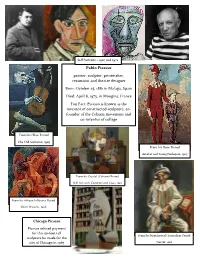

Pablo Picasso Study Guide

Self Portraits – 1907 and 1972 Pablo Picasso painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and theatre designer Born: October 25, 1881 in Malaga, Spain Died: April 8, 1973, in Mougins, France Fun Fact: Picasso is known as the inventor of constructed sculpture, co- founder of the Cubism movement and co-inventor of collage From his Blue Period The Old Guitarist, 1903 From his Rose Period Acrobat and Young Harlequin, 1905 From his Crystal (Cubism) Period Still Life with Compote and Glass, 1915 From his African Influence Period Three Women, 1908 Chicago Picasso Picasso refused payment for this 50-foot tall From his Neoclassical/ Surrealism Period sculpture he made for the city of Chicago in 1967 Pierrot, 1918 Book List: 100 Pablo Picassos By, Violet Lemay An Interview With Pablo Picasso By, Neil Cox Just Behave, Pablo Picasso! By, Jonah Winter Pablo Picasso By, Mike Venezia 13 Artists Children Should Know By, Angela Wenzel Websites: Pablo Picasso - The Picasso myth | Britannica Pablo Picasso - Wikipedia Picasso Quotes | Art Quotes by Pablo Picasso | Art Therapy (arttherapyblog.com) Activities: 1. Create a Picasso face. Use paint, magazine pictures, cut up construction paper or clay. 2. Make collage art. 3. Picasso color page - coloring-page.jpg (377×480) (artsycraftsymom.com) 4. Picasso’s Blue period was during a sad time in his life. His Rose Period was during a time filled with joy and love. His art reflects his moods in colors, subjects and style. Create your own Blue Period/ Rose Period paintings. Or find your own mood and paint according to that. 5. Watch this video about Picasso - (2) 10 Amazing Facts about Spanish Artist Pablo Picasso - YouTube Art Appreciation – Pablo Picasso Thank you for downloading the Pablo Picasso Study Guide. -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 8, 2017 CONTACT: Mayor's Press

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 8, 2017 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR EMANUEL CELEBRATES THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE CHICAGO PICASSO ON DALEY PLAZA Everyone’s Picasso commemorates the 1967 unveiling of Picasso’s first large-scale civic sculpture in America Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) today celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Chicago Picasso at Daley Plaza. Called Everyone’s Picasso, the ceremony restaged the original 1967 unveiling of the sculpture. The Chicago Picasso is considered to be artist Pablo Picasso’s first large-scale civic sculpture in America. “Chicago’s Picasso exemplifies the lasting legacy public art has on the fabric of our city,” said Mayor Rahm Emanuel. “A fitting anniversary as part of the 2017 Year of Public Art, the Picasso has inspired artists, sculptors, painters and poets to make the City of Chicago a global hub for culture and art.” While the Picasso attracted mixed reviews when it was unveiled on August 15, 1967, it has since become an enduring influence on Chicago’s public art. It has been featured in popular films like The Blues Brothers, The Fugitive, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Now a beloved symbol of Chicago, the Picasso is central to hundreds of events in Daley Plaza, including creative arts performances and farmers markets. “Chicago’s reputation as an innovator and leader in the presentation of public art continues to this day,” said DCASE Commissioner Mark Kelly. “The Picasso helped spark Chicago’s legacy of public art and has inspired artists across the world for decades.” The commemoration ceremony, called Everyone’s Picasso, was conceived by artist and historian Paul Durica. -

Marion Harding Artist

MARION HARDING – People, Places and Events Selection of articles written and edited by: Ruan Harding Contents People Antoni Gaudí Arthur Pan Bryher Carl Jung Hugo Perls Ingrid Bergman Jacob Moritz Blumberg Klaus Perls Marion Harding Pablo Picasso Paul-Émile Borduas Pope John Paul II Theodore Harold Maiman Places Chelsea, London Hyères Ireland Portage la Prairie Vancouver Events Nursing Painting Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Ernstblumberg/Books/Marion_Harding_- _People,_Places_and_Events" Categories: Wikipedia:Books Antoni Gaudí Antoni Gaudí Antoni Gaudí in 1878 Personal information Name Antoni Gaudí Birth date 25 June 1852 Birth place Reus, or Riudoms12 Date of death 10 June 1926 (aged 73) Place of death Barcelona, Catalonia, (Spain) Work Significant buildings Sagrada Família, Casa Milà, Casa Batlló Significant projects Parc Güell, Colònia Güell 1See, in Catalan, Juan Bergós Massó, Gaudí, l'home i la obra ("Gaudí: The Man and his Work"), Universitat Politècnica de Barcelona (Càtedra Gaudí), 1974 - ISBN 84-600-6248-1, section "Nacimiento" (Birth), pp. 17-18. 2 "Biography at Gaudí and Barcelona Club, page 1" . http://www.gaudiclub.com/ingles/i_vida/i_vida.asp. Retrieved on 2005-11-05. Antoni Plàcid Guillem Gaudí i Cornet (25 June 1852–10 June 1926) – in English sometimes referred to by the Spanish translation of his name, Antonio Gaudí 345 – was a Spanish Catalan 6 architect who belonged to the Modernist style (Art Nouveau) movement and was famous for his unique and highly individualistic designs. Biography Birthplace Antoni Gaudí was born in the province of Tarragona in southern Catalonia on 25 June 1852. While there is some dispute as to his birthplace – official documents state that he was born in the town of Reus, whereas others claim he was born in Riudoms, a small village 3 miles (5 km) from Reus,7 – it is certain that he was baptized in Reus a day after his birth. -

Pablo Picasso Picasso Was Born in Spain in 1881 Picasso Was His Mother’S Last Name His Father, Ruiz, Was a Painter Picasso Started Drawing at a Young Age

PABLO PICASSO PICASSO WAS BORN IN SPAIN IN 1881 PICASSO WAS HIS MOTHER’S LAST NAME HIS FATHER, RUIZ, WAS A PAINTER PICASSO STARTED DRAWING AT A YOUNG AGE HIS FIRST WORDS WERE “PIZ PIZ” WHICH COMES FROM THE SPANISH WORD FOR PENCIL LAPIZ HIS FATHER KNEW HE WAS TALENTED. HE TAUGHT PICASSO THE BASICS OF DRAWING AND PAINTING. PICASSO ORIGINAL AT AGE 8 AT 13, PICASSO WENT TO ART SCHOOL WHERE HIS FATHER TAUGHT. HE BEGAN TO PAINT LIKE THIS ... PICASSO AGE 14 PICASSO LEARNED THE BASICS OF FORMAL ART TRAINING ACADEMIC REALISM WHERE WAS THE ART CAPITAL OF EUROPE IN THE 1900’s? CAFE SCENE PICASSO HUNG OUT WITH FAMOUS ART COLLECTORS IN PARIS HE BECAME FRIENDS WITH OTHER ARTISTS LIKE MATISSE HE FREQUENTED CAFES TO TALK ART AND IDEAS PICASSO’S TEEN YEARS HE LIVED AWAY FROM HOME IN PARIS. HE LIVED IN POOR CONDITIONS, AND THIS WAS A HARD TIME IN HIS LIFE. PICASSO BEGAN TO PAINT: SOLITUDE HUNGER MISERY SOCIAL OUTCASTS ! IT IS KNOWN AS HIS … BLUE PERIOD BUT THEN PICASSO FELL IN LOVE HE STARTED PAINTING MORE UPBEAT AND OPTIMISTIC THEMES, INCLUDING CIRCUS PERFORMERS, ACROBATS, AND HARLEQUINS. ! THIS WAS CALLED HIS … ROSE PERIOD PICASSO BECAME INSPIRED BY AFRICAN ART AFRICAN PERIOD THEN PICASSO BECAME RAD HE AND ARTIST GEORGES BRAQUE CREATED A NEW ART FORM CUBISM GEOMETRICAL SUBJECTS ARE ANALYZED, BROKEN UP AND REASSEMBLED INTO AN ABSTRACT FORM OBJECTS ARE VIEWED FROM ALL SIDES ANALYTICAL CUBISM DECONSTRUCTING OBJECTS REMOVING BRIGHT COLOR SYNTHETIC CUBISM CUBISM DONE IN PAPER COLLAGE TEXTURE Can you guess what this is called? THE THREE MUSICIANS A HARLEQUIN, PIERROT AND A MONK (OR PICASSO AND TWO OTHER FRIENDS). -

Creating a Pipeline from Classroom to Career 2017 Annual Conference

2017 Annual Conference Creating a Pipeline from Classroom to Career Chicago, Illinois Hilton Chicago Hotel July 6 – 9, 2017 Program printed compliments of Santillana USA Santillana ad The American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese (AATSP) is committed to ensuring that no individual is deprived of the opportunity of membership and/or participation in the conference on the basis of age, color, height, weight, creed, disability, marital status, sexual preference, national origin, political affiliation, race, religion or sex. The conference facility is fully accessible and compliant with the American with Disabilities Act (ADA). To make a request for special accommodations please contact the AATSP via email ([email protected]) or telephone at 248-960- 2180 by June 10, 2017 to provide information detailing the nature of your disability and need for accommodation. With respect to all matters related to accommodation, the AATSP will only communicate with the candidate, a professional knowledgeable about the candidate’s disability or impairment, or the candidate’s authorized representative. 2017 AATSP Conference — 1 2017 AATSP Conference — 2 2016 CONFERENCE PROGRAM AT A GLANCE WEDNESDAY, JULY 5 12:15pm – 12:45pm Sharing SHA Chapter Successes 8:00am - 5:00pm AATSP Board of Directors Meeting 12:15pm – 12:45pm Santillana USA Session 2:00pm - 4:30pm Registration Open (8th North Street 12:45pm – 2:00pm Exhibit Break with Refreshments Lobby Level) SATURDAY, JULY 8 (DAY 3) THURSDAY, JULY 6 (DAY 1) 7:45am – 8:15am Session Block 9 -

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2013/June

AL Direct, June 5, 2013 Contents American Libraries Online | ALA News | Booklist Online Chicago Update | Division News | Awards & Grants | Libraries in the News Issues | Tech Talk | E-Content | Books & Reading | Tips & Ideas Libraries on Film | Digital Library of the Week | Calendar The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | June 5, 2013 American Libraries Online American Libraries June issue The ALA Annual Conference Preview issue of American Libraries is now available online. It highlights all of the conference’s must-see events, speakers, and forums, and dishes on the best places to eat in Chicago while visiting. Other June issue features include: tips on building audiobook collections for youth, a look at charter school libraries, and a guide to apps for kids ALA Annual Conference, with special needs.... Chicago, June 27–July 2. AL: Inside Scoop, May 31 Newsmaker: A conversation with Alice Walker Alice Walker is a remarkably prolific and versatile writer of conscience. She will always be remembered for her indelible and life-changing masterpiece, The Color Purple. Walker will be appearing at the ALA Annual Conference in Chicago as an Auditorium Speaker on July 1. On behalf of American Libraries, Booklist Senior Editor Donna Seaman reached Walker at her home in Mexico.... American Libraries column, June The American Libraries ALA Annual Conference 2013 Annual Conference preview, as well as its preview popular dining guide, is ALA welcomes colleagues, vendors, and now available. Get the other attendees to Chicago for the Chicago insiders’ view, Association’s 137th Annual Conference, and find out what we’re June 27–July 2. -

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pablo_Picasso This name uses Spanish naming customs: the first or paternal family name is Ruiz and the second or maternal family name is Picasso. Pablo Picasso Picasso in 1908 Born Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso[1] 25 October 1881 Málaga, Spain Died 8 April 1973 (aged 91) Mougins, France Resting Château of Vauvenargues place 43.554142°N 5.604438°E Nationality Spanish Education José Ruiz y Blasco (father) Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando Known for Painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking, ceramics, stage design, writing Notable La Vie (1903) work Family of Saltimbanques (1905) Les Demoiselles d'Avignon(1907) Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1910) Girl before a Mirror (1932) Le Rêve (1932) Guernica (1937) The Weeping Woman (1937) Movement Cubism, Surrealism Spouse(s) Olga Khokhlova (m. 1918; died 1955) Jacqueline Roque (m. 1961) Pablo Ruiz Picasso (/pɪˈkɑːsoʊ, -ˈkæsoʊ/;[2] Spanish: [ˈpaβlo piˈkaso]; 25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, stage designer, poet and playwright who spent most of his adult life in France. Regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, he is known for co-founding the Cubist movement, the invention of constructed sculpture,[3][4] the co- invention of collage, and for the wide variety of styles that he helped develop and explore. Among his most famous works are the proto- Cubist Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), and Guernica (1937), a dramatic portrayal of the bombing of Guernica by the German and Italian airforces during the Spanish Civil War. -

University Village

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 18, 2008, Designation List 407 LP-2300 UNIVERSITY VILLAGE, 100 and 110 Bleecker Street (aka Silver Towers I & II, 98-122 Bleecker Street and 40-58 West Houston Street) and 505 LaGuardia Place (aka 487-507 LaGuardia Place and 64-86 West Houston Street). Built 1964-67; I. M. Pei & Associates, architect; James Ingo Freed, chief designer. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan, Block 524, Lot 1 and Lot 66, in part, beginning at the southwest corner of Lot 1 and extending northerly along the western property line of Lot 1 coincident with the easterly side of LaGuardia Place 248 feet; then easterly along a section of the northern property line of Lot 1 that runs parallel to Bleecker Street 124 feet; then northerly 130.18 feet along a section of the western property line of Lot 1 that parallels LaGuardia Place; then easterly along the northern property line of Lot 1 and a section of the northern property line of Lot 66 coincident with the southerly side of Bleecker Street 302.24 feet; then southerly and parallel to Mercer Street 336.52 feet; then easterly and parallel with West Houston Street 9.92 feet; then southerly and parallel with Mercer Street to the southern property line of Lot 66; then westerly along a section of the southern property line of Lot 66 and the southern property line of Lot 1 coincident with the northerly side of West Houston Street 437.35 feet to the point of beginning. On June 24, 2008 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of University Village and the proposed designation of the related Landmark site. -

2006 Commission of Chicago

Public Building PBC2006 Commission of Chicago Celebrating 40 Years of “The Picasso” annual report Table of Contents Message from the Chairman 2 Message from the Executive Director 4 PBC Board of Commissioners 6 About the PBC 8 The Picasso at 40 10 Chicago Public Schools 12 Chicago Public Library 14 Chicago Park District and Campus Parks 16 City of Chicago 18 Chicago Police Department 20 Chicago Fire Department 22 City Colleges of Chicago 24 Financial Summary 26 Project Map 28 Picasso Illustrations 30 1 PBC 2006 Annual Report 2 PBC2006 Message from the Message from PBC 2006 Annual ReportPBC 2006 Chairman In the last decade Chicago has led the nation in our efforts to enhance neighborhood quality of life by building and renovating community anchors across our city. Through our efforts to build and renovate libraries, police stations, fire houses, senior centers, campus parks and other public facilities, we have made Chicago a city in which people want to live and businesses want to locate. The Public Building Commission of Chicago (PBC) has played a key role in this achievement by managing the construction or rehabilitation of many of these facilities. Construction and renovation projects are indeed major contributors to Chicago’s quality of life, but not just the bricks and mortar part. Public art is also a component of many PBC projects, with the oldest example dating back to our first endeavor, the Chicago Civic Center, now known as the Richard J. Daley Center. Adorning Daley Plaza is the massive nameless steel sculpture that many people simply call “The Picasso.” It is the work that spurred the City of Chicago’s public art program and in 2007 the city proudly celebrates the 40th anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s iconic creation. -

The One Fact That Everyone Could Agree on About the New Thing Was That It Was a Thing

lokale Festplatte - KB3-11~1\KB3-11.JOB 4.10.2011 12:50 Seite 47 Rebecca Zorach Fireplug, Flower, Baboon: The Democratic Thing in Late 1960s Chicago The one fact that everyone could agree on about the new thing was that it was a thing. Though even there, it might be, instead, a «thing». It was, again and again, «that thing»; it was «a monstrous ‹thing› that defies description»; it was a «huge, rust-colored object», a «monstrosity», a «whatsit» or «whatizzit».1 Ed Sopko, the construction foreman, said in an interview about his experience working on the thing: First thing anyone’d ask you is what is it. Then you’d try to explain to them ‹well, I really don’t know myself›, you know. Then you’d ask them [to] say – ‹what does it look like›? A lot of ‘em’d say ‹well, just nothing›. Then another guy’d say ‹well, it look[s] like – like a big bird›. And then lot of people would say, ‹well, they could see a woman›. Some people liked it and some didn’t.2 Artists have always turned raw «stuff» into art, and, arguably, have always made artworks that are also «things». But in the twentieth century the practice of taking objects that already had their own distinct identities as things and turning them into art became enshrined as standard practice. With the readymade, art became art through a process that has been called «nomination» – the simple act of naming as.3 But what would it mean to operate the reverse process, to name an artwork a «mere» thing and thus to make it so? When Reformation-era iconoclasts destroyed religious artworks they reduced them to their raw materials, taunting them to speak if they possess spirit.4 Psalm 115:4 insists on the materiality of the idols: «Their idols are silver and gold». -

Carlos Gomez Martin

Pablo Picasso -NOMBRE : Carlos Gomez Martin -FECHA : 8 de Febrero -CURSO : 6º A BIOGRAFIA Pintor y escultor español, considerado uno de los artistas más importantes del siglo XX. Artista polifacético fue único y genial en todas sus facetas, inventor de formas, innovador de técnicas y estilos, artista gráfico y escultor, siendo uno de los creadores más prolíficos de toda la historia, con más de 20.000 trabajos en su haber. Picasso nació en Málaga el 25 de octubre de 1881, hijo de María Picasso López y del profesor de arte José Ruiz Blasco. Hasta 1898 siempre utilizó los apellidos paterno y materno para firmar sus obras, pero alrededor de 1901 abandonó el primero para utilizar desde entonces sólo el apellido de la madre. El genio de Picasso se pone ya de manifiesto desde fechas muy tempranas, a la edad de 10 años hizo sus primeras pinturas y a los 15 aprobó con brillantez los exámenes de ingreso en la Escuela de Bellas Artes de Barcelona, con su gran lienzo Ciencia y caridad (1897, Museo Picasso, Barcelona), que representa, dentro aún de la corriente academicista, a un médico, una monja y un niño junto a la cama de una mujer enferma, ganó una medalla de oro. Entre 1900 y 1902 Picasso hizo tres viajes a París, estableciéndose finalmente allí en 1904. El ambiente bohemio de las calles parisinas le fascinó desde un primer momento, mostrando en sus cuadros de la gente en los salones de baile y en los cafés la asimilación del postimpresionismo de Paul Gauguin y del simbolismo de los pintores nabis.