The One Fact That Everyone Could Agree on About the New Thing Was That It Was a Thing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pablo Picasso Study Guide

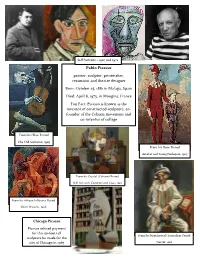

Self Portraits – 1907 and 1972 Pablo Picasso painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and theatre designer Born: October 25, 1881 in Malaga, Spain Died: April 8, 1973, in Mougins, France Fun Fact: Picasso is known as the inventor of constructed sculpture, co- founder of the Cubism movement and co-inventor of collage From his Blue Period The Old Guitarist, 1903 From his Rose Period Acrobat and Young Harlequin, 1905 From his Crystal (Cubism) Period Still Life with Compote and Glass, 1915 From his African Influence Period Three Women, 1908 Chicago Picasso Picasso refused payment for this 50-foot tall From his Neoclassical/ Surrealism Period sculpture he made for the city of Chicago in 1967 Pierrot, 1918 Book List: 100 Pablo Picassos By, Violet Lemay An Interview With Pablo Picasso By, Neil Cox Just Behave, Pablo Picasso! By, Jonah Winter Pablo Picasso By, Mike Venezia 13 Artists Children Should Know By, Angela Wenzel Websites: Pablo Picasso - The Picasso myth | Britannica Pablo Picasso - Wikipedia Picasso Quotes | Art Quotes by Pablo Picasso | Art Therapy (arttherapyblog.com) Activities: 1. Create a Picasso face. Use paint, magazine pictures, cut up construction paper or clay. 2. Make collage art. 3. Picasso color page - coloring-page.jpg (377×480) (artsycraftsymom.com) 4. Picasso’s Blue period was during a sad time in his life. His Rose Period was during a time filled with joy and love. His art reflects his moods in colors, subjects and style. Create your own Blue Period/ Rose Period paintings. Or find your own mood and paint according to that. 5. Watch this video about Picasso - (2) 10 Amazing Facts about Spanish Artist Pablo Picasso - YouTube Art Appreciation – Pablo Picasso Thank you for downloading the Pablo Picasso Study Guide. -

ERS Course on Interstitial Lung Disease Heidelberg, Germany 4-6 November, 2019

ERS Course on Interstitial Lung Disease Heidelberg, Germany 4-6 November, 2019 Course Venue The course will take place at the Rohrbacher Schlösschen on the grounds of the Thoraxklinik Heidelberg: Thoraxklinik Heidelberg Parkstrasse 1 Entrance at corner of Parkstrasse and Amalienstrasse approximately opposite Parkstrasse 31 (Parkstrasse 1 is the address for several buildings) 69126 Heidelberg Access to the Thoraxklinik from Heidelberg train station The Heidelberg Central Railway Station is about 15 minutes by car from the Thoraxklinik. You can take a taxi or tram to the hospital from here. A taxi ride will take about 10 to 15 minutes depending on traffic and will cost approximately €20.00. For the tram take line 24 towards “Leimen/Rohrbach Süd". Get off at the stop “Ortenauerstraße”, located 500 meters from the Rohrbacher Schlösschen. Tram tickets range from €2,50 for a single trip to €15,80 for a three- day ticket. A) tram stop Ortenauerstrasse B) Rohrbacher Schlösschen Alight from the tram at stop Ortenauerstrasse. Go north following Römerstrasse/Karlsruher Strasse for 200 m. Turn right onto Parkstrasse and follow Parkstrasse for 250 metres. The Rohrbacher Schlösschen will be located to your right. For further information on public transportation in and around Heidelberg please refer to: o https://www.tourism- heidelberg.com/destination/getting- around/bus-and-tram/index_eng.html ERS Course on Interstitial Lung Disease Heidelberg, Germany Transportation to Heidelberg from Frankfurt / Stuttgart Airports From Frankfurt Airport: • Via Mannheim: 2 direct trains an hour will take you to Mannheim Train Station in 35 minutes approximately. From there, you need to change to a train going to Heidelberg. -

Inter-Rater Reliability of Neck Reflex Points In

Forschende Komplementärmedizin Original Article · Originalarbeit Wissenschaft | Praxis | Perspektiven Forsch Komplementmed 2016;23:223–229 Published online: June 23, 2016 DOI: 10.1159/000447506 Inter-Rater Reliability of Neck Reflex Points in Women with Chronic Neck Pain a,b c d e Stefan Weinschenk Richard Göllner Markus W. Hollmann Lorenz Hotz e f b g Susanne Picardi Katharina Hubbert Thomas Strowitzki Thomas Meuser for the h Heidelberg University Neural Therapy Education and Research Group (The HUNTER group) a Outpatient Practice Drs. Weinschenk, Scherer & Co., Karlsruhe, Germany; b Department of Gynecological Endocrinology and Fertility Disorders, Women’s Hospital, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany; c Institute of Educational Science, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; d Department of Anesthesiology AMC Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e Department of Anesthesiology, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany; f Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Frankfurt-Hoechst Hospital, Frankfurt/M., Germany; g Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Marienkrankenhaus, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany; h The Heidelberg University Neural Therapy Education and Research Group, Women’s Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany Keywords Schlüsselwörter Cervical pain · Muscular trigger points · Nackenschmerzen · Muskel-Triggerpunkte · Neuroreflektorische Neuroreflectory changes · Dental focus · Neural therapy Veränderungen · Zahnherde · Neuraltherapie Summary Zusammenfassung Background: Neck reflex points (NRP) are tender soft tissue Hintergrund: Nackenreflexpunkte (NRP, Adler-Langer-Punkte) areas of the cervical region that display reflectory changes in sind schmerzhafte Bindegewebsareale an Hals und Nacken, die response to chronic inflammations of correlated regions in the bei chronischen Entzündungen des viszeralen Kraniums auftre- visceral cranium. Six bilateral areas, NRP C0, C1, C2, C3, C4 and ten können. Je 6 Punkte, NRP C0, C1, C2, C3, C4 und C7, lassen C7, are detectable by palpating the lateral neck. -

Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg Gmbh Springer Series in Synergetics

Self-Organization and the City Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Springer Series in Synergetics An ever increasing number of scientific disciplines deal with complex systems. These are systems that are composed of many parts which interact with one another in a more or less complicated manner. One of the most striking features of many such systems is their ability to spontaneously form spatial or temporal structures. A great variety of these structures are found, in both the inanimate and the living world. In the inanimate world of physics and chemistry, examples include the growth of crystals, coherent oscillations oflaser light, and the spiral structures formed in fluids and chemical reactions. In biology we encounter the growth of plants and animals (morphogenesis) and the evolution of species. In medicine we observe, for instance, the electromagnetic activity of the brain with its pronounced spatio-temporal structures. Psychology deals with characteristic features ofhuman behavior ranging from simple pattern recognition tasks to complex patterns of social behavior. Examples from sociology include the formation of public opinion and cooperation or competition between social groups. In recent decades, it has become increasingly evident that all these seemingly quite different kinds of structure formation have a number of important features in common. The task of studying analo gies as weil as differences between structure formation in these different fields has proved to be an ambitious but highly rewarding endeavor. The Springer Series in Synergetics provides a forum for interdisciplinary research and discussions on this fascinating new scientific challenge. It deals with both experimental and theoretical aspects. The scientific community and the interested layman are becoming ever more conscious of concepts such as self-organization, instabilities, deterministic chaos, nonlinearity, dynamical systems, stochastic processes, and complexity. -

T Helper Cell Infiltration in Osteoarthritis-Related Knee Pain

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article T Helper Cell Infiltration in Osteoarthritis-Related Knee Pain and Disability 1, 1, 1 1 Timo Albert Nees y , Nils Rosshirt y , Jiji Alexander Zhang , Hadrian Platzer , Reza Sorbi 1, Elena Tripel 1, Tobias Reiner 1, Tilman Walker 1, Marcus Schiltenwolf 1 , 2 2 1, 1, , Hanns-Martin Lorenz , Theresa Tretter , Babak Moradi z and Sébastien Hagmann * z 1 Clinic for Orthopedics and Trauma Surgery, Center for Orthopedics, Trauma Surgery and Spinal Cord Injury, Heidelberg University Hospital, Schlierbacher Landstr. 200a, 69118 Heidelberg, Germany; [email protected] (T.A.N.); [email protected] (N.R.); [email protected] (J.A.Z.); [email protected] (H.P.); [email protected] (R.S.); [email protected] (E.T.); [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (B.M.) 2 Department of Internal Medicine V, Division of Rheumatology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 410, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; [email protected] (H.-M.L.); [email protected] (T.T.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-622-1562-6289; Fax: +49-622-1562-6348 These authors contributed equally to this study. y These authors share senior authorship. z Received: 16 June 2020; Accepted: 23 July 2020; Published: 29 July 2020 Abstract: Despite the growing body of literature demonstrating a crucial role of T helper cell (Th) responses in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis (OA), only few clinical studies have assessed interactions between Th cells and OA—related symptoms. -

Welcome to the Joint DIERS Meeting 2019 in Karlsruhe (Germany)

Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jürgen Schmidt, Dipl.-Ing. Sara Claramunt Welcome to the Joint DIERS Meeting 2019 in Karlsruhe (Germany) CSE-INSTITUTE – COMPETENCE CENTER FOR SAFETY TECHNOLOGY [email protected] Forschung & Lehre in Sicherheitstechnik Conference schedule / Travel plan 21st May 2019 22nd May 2019 23rd May 2019 24th May 2019 8 am – 12 pm Conference Conference Conference 12 pm – 01 pm Lunch Lunch Lunch Conference Hotel → CSE Conference Arrival 15 min ride 01 pm – 04 pm Train fast connection Visit Center of Safety Frankfurt Airport → Excellence CSE Karlsruhe Central Station - High Pressure Loop 60 min ride - Live- Type testing 04 pm – 06 pm CSE → Heidelberg Departure 30 min ride Bus shuttle Bus shuttle Karlsruhe Central Station → Dinner at german brewery Visit to historic town Hotel Karlsruhe Central Hotel 06 pm – open end „Vogelbräu“ Heidelberg and Gala Dinner Station 10 min ride › 1 minute to walk from hotel › Self-payment basis Train fast connection Heidelberg → Hotel Karlsruhe Central Station 40 min ride →Frankfurt Airport 2018 CSE CENTER OF SAFETY EXCELLENCE | CSE-INSTITUT.DE 2 Hotel & conference - Karlsruhe Baltic See North See Berlin GERMANY • Karlsruhe – Heidelberg: 30 miles • Karlsruhe – Straßbourg: 50 miles • Karlsruhe – Frankfurt: 75 miles Frankfurt • Karlsruhe – Munich: 180 miles Heidelberg Karlsruhe Strasbourg Stuttgart Munich The Alps „nationalflaggen.de“; URL: http://www.nationalflaggen.de/flaggen-europa.html; [17.04.2018] 2018 CSE CENTER OF SAFETY EXCELLENCE | CSE-INSTITUT.DE 3 Meeting Location: Karlsruhe - Ettlingen » Karlsruhe is the seat of the two highest courts in Germany. Its most remarkable building is Karlsruhe Palace, which was built in 1715. » The Technologieregion Karlsruhe is a loose confederation of the region's cities in order to promote high tech industries; today, about 20% of the region's jobs are in research and development. -

2004-2005 Heidelberg College Catalog Heidelberg 310 East Market Street College Tiffin, Ohio 44883-2462 1.800.Heidelberg

Non-Profit Org. Heidelberg U.S. Postage PAID College Heidelberg 2004-2005 Heidelberg College Catalog Heidelberg 310 East Market Street College Tiffin, Ohio 44883-2462 1.800.Heidelberg www.heidelberg.edu 2004 - 2005 CATALOG Academic Year Calendar Introduction ' Semester I 2004-2005 1 Sun. Aug. 29 First-year students and transfers arrive Mon. Aug. 30 Registration verification Tues. Aug. 31 Classes begin Thur. Oct. 14 Long weekend recess begins after last class Mon. Oct. 18 Classes resume Tues. Nov. 23 Thanksgiving recess begins after last class Mon. Nov. 29 Classes resume Fri. Dec. 10 Classes end Mon. Dec. 13 Final exams begin Thur. Dec. 16 Christmas recess begins after last exam ' Semester II 2004-2005 Sun. Jan. 9 Registration verification Mon. Jan. 10 Classes begin Mon. Jan. 17 No classes—Martin Luther King Day Thur. Mar. 10 Spring recess begins after last class Tues. Mar. 29 Classes resume Thur. May 5 Classes end Fri. May 6 Final exams begin Wed. May 11 Final exams end Sun. May 15 Baccalaureate, Undergraduate and Graduate Commencement ' Summer 2005 Mon. May 23 Term 1 classes begin Fri. June 24 Term 1 classes end Mon. June 27 Term 2 classes begin Fri. July 29 Term 2 classes end Mon. May 23 Term 3 classes begin Fri. July 29 Term 3 classes end Sources of Information HEIDELBERG COLLEGE, Tiffin, Ohio 44883-2462 2 TELEPHONE SUBJECT OFFICE AREA CODE: 419 Admission Vice President for Enrollment 448-2330 Advanced Standing Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of the College 448-2216 Alumni Affairs Director of Alumni and Parent Relations -

Perspectives

Annual Report 2020/2021 Pers Pectives To our investors Our strategy Our Objective i mPrOve PrOfitability i ncrease strengthen enterPrise cOre business value DevelOP new grOwth for our areas shareholders CT oN eN s Two-year overview CONTENTS Pers Pectives in packaging printing in china in digital business models in new markets Our PersPectives f oCus oN paCkagiNg priNTiNg: Market and technology leadership along the entire value chain in the folding box and label segment l everage MarkeT poTeNTial iN ChiNa: above-average participation in market growth and expansion of production Acc eleraTe digiTalizaTioN: f urther expansion of contract business, digital platforms and software range Tra Nsfer TeChNology: successful transition from printing presses to additional industries section Financial Finanzteil go to To our investors Two-yAR E ovERvIEw – HEIDElBERg gRoup Figures in € millions 2019 / 2020 2020 / 2021 Incoming orders 2,362 2,000 Net sales 2,349 1,913 EBITDA 1) 102 146 in percent of sales 4.3 7.6 Result of operating activities excluding restructuring result 6 69 Net result after taxes – 343 – 43 in percent of sales – 14.6 – 2.2 Research and development costs 126 87 Investments 110 78 Equity 202 109 Net debt 2) 43 67 Free cash flow 225 3) 40 Earnings per share in € – 1.13 – 0.14 Number of employees at financial year-end 4) 11,316 10,212 1) Result of operating activities before interest and taxes and before depreciation and amortization, excluding restructuring result 2) Net total of financial liabilities and cash and cash equivalents and short-term securities 3) Including inflow from trust assets of around € 324 million 4) Number of employees excluding trainees In individual cases, rounding may result in discrepancies concerning the totals and percentages contained in this Annual Report. -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 8, 2017 CONTACT: Mayor's Press

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 8, 2017 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR EMANUEL CELEBRATES THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE CHICAGO PICASSO ON DALEY PLAZA Everyone’s Picasso commemorates the 1967 unveiling of Picasso’s first large-scale civic sculpture in America Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) today celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Chicago Picasso at Daley Plaza. Called Everyone’s Picasso, the ceremony restaged the original 1967 unveiling of the sculpture. The Chicago Picasso is considered to be artist Pablo Picasso’s first large-scale civic sculpture in America. “Chicago’s Picasso exemplifies the lasting legacy public art has on the fabric of our city,” said Mayor Rahm Emanuel. “A fitting anniversary as part of the 2017 Year of Public Art, the Picasso has inspired artists, sculptors, painters and poets to make the City of Chicago a global hub for culture and art.” While the Picasso attracted mixed reviews when it was unveiled on August 15, 1967, it has since become an enduring influence on Chicago’s public art. It has been featured in popular films like The Blues Brothers, The Fugitive, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Now a beloved symbol of Chicago, the Picasso is central to hundreds of events in Daley Plaza, including creative arts performances and farmers markets. “Chicago’s reputation as an innovator and leader in the presentation of public art continues to this day,” said DCASE Commissioner Mark Kelly. “The Picasso helped spark Chicago’s legacy of public art and has inspired artists across the world for decades.” The commemoration ceremony, called Everyone’s Picasso, was conceived by artist and historian Paul Durica. -

Heidelberg-Karlsruhe-Strasbourg Geometrie-Tag

Universität Heidelberg, Prof. Dr. A. Wienhard, Mathematisches Institut, Mathematikon, INF 205 Heidelberg-Karlsruhe-Strasbourg Geometrie-Tag „Liouville current, intersection and pressure metric revisited“ Prof. Dr. Andrés Sambarino, Université Paris VI Pierre et Marie Curie Freitag, 01.12.2017, 11.00 Uhr, SR C, INF 205 „Riemann surfaces and line complexes“ Firat Yasar, Université de Strasbourg Freitag, 01.12.2017, 14.00 Uhr, SR B, INF 205 „Moduli spaces of non-negatively curved Riemannian metrics“ Prof. Dr. Wilderich Tuschmann, KIT, Karlsruhe Freitag, 01.12.2017, 15.30 Uhr, SR B, INF 205 Universität Heidelberg, Prof. Dr. A. Wienhard, Mathematisches Institut, Mathematikon, INF 205 10. Heidelberg-Karlsruhe-Strasbourg Geometrie-Tag „Liouville current, intersection and pressure metric revisited“ Prof. Dr. Andrés Sambarino, Université Paris VI Pierre et Marie Curie The purpose of the talk is to explain a construction of a Liouville current for a representation in the Hitchin component. Bonahon's intersection between two such currents can be computed. We will also explain the relation with a pressure metric. This is joint work with D. Canary, M. Bridgeman and F. Labourie. „Riemann surfaces and line complexes“ Firat Yasar, Université de Strasbourg Firstly we will recall the uniformisation theorem and speak about how to uniformise multiply connected regions. The second part of this talk will include several graphs defined on Riemann surfaces. We plan to explain these graphs known as line complexes, Speiser trees and dessins d’enfants and the relation between them. At the end we will give several examples of them. „Moduli spaces of non-negatively curved Riemannian metrics“ Prof. Dr. -

Welcome to Southwest Germany

WELCOME TO SOUTHWEST GERMANY THE BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG VACATION GUIDE WELCOME p. 2–3 WELCOME TO SOUTHWEST GERMANY In the heart of Europe, SouthWest Germany Frankfurt Main FRA (Baden-Württemberg in German) is a cultural crossroads, c. 55 km / 34 miles bordered by France, Switzerland and Austria. But what makes SouthWest Germany so special? Mannheim 81 The weather: Perfect for hiking and biking, NORTHERN BADENWÜRTTEMBERGJagst Heidelberg from the Black Forest to Lake Constance. 5 Neckar Kocher Romantic: Some of Europe’s most romantic cities, 6 Andreas Braun Heilbronn Managing Director such as Heidelberg and Stuttgart. Karlsruhe State Tourist Board Baden-Württemberg Castles: From mighty fortresses to fairy tale palaces. 7 Pforzheim Christmas markets: Some of Europe’s most authentic. Ludwigsburg STUTTGART Karlsruhe REGION Baden-Baden Stuttgart Wine and food: Vineyards, wine festivals, QKA Baden-Baden Michelin-starred restaurants. FRANCE STR Rhine Murg Giengen Cars and more cars: The Mercedes-Benz 8 an der Brenz Outletcity and Porsche museums in Stuttgart, Ki n zig Neckar Metzingen Ulm Munich the Auto & Technik Museum in Sinsheim. MUC SWABIAN MOUNTAINS c. 156 km / 97 miles 5 81 Hohenzollern Castle Value for money: Hotels, taverns and restaurants are BLACK FOREST Hechingen Danube Europa-Park BAVARIA7 well-priced; inexpensive and efficient public transport. Rust Real souvenirs: See cuddly Steiff Teddy Bears Danube and cuckoo clocks made in SouthWest Germany. Freiburg LAKE CONSTANCE REGION Spas: Perfect for recharging the batteries – naturally! Black Forest Titisee-Neustadt Titisee Highlands Feldberg 96 1493 m Schluchsee 98 Schluchsee Shopping: From stylish city boutiques to outlet shopping. Ravensburg Mainau Island People: Warm, friendly, and English-speaking.