Oral History of William Hartmann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pablo Picasso Study Guide

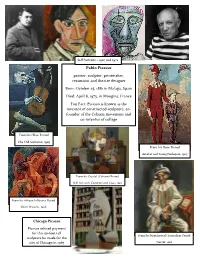

Self Portraits – 1907 and 1972 Pablo Picasso painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and theatre designer Born: October 25, 1881 in Malaga, Spain Died: April 8, 1973, in Mougins, France Fun Fact: Picasso is known as the inventor of constructed sculpture, co- founder of the Cubism movement and co-inventor of collage From his Blue Period The Old Guitarist, 1903 From his Rose Period Acrobat and Young Harlequin, 1905 From his Crystal (Cubism) Period Still Life with Compote and Glass, 1915 From his African Influence Period Three Women, 1908 Chicago Picasso Picasso refused payment for this 50-foot tall From his Neoclassical/ Surrealism Period sculpture he made for the city of Chicago in 1967 Pierrot, 1918 Book List: 100 Pablo Picassos By, Violet Lemay An Interview With Pablo Picasso By, Neil Cox Just Behave, Pablo Picasso! By, Jonah Winter Pablo Picasso By, Mike Venezia 13 Artists Children Should Know By, Angela Wenzel Websites: Pablo Picasso - The Picasso myth | Britannica Pablo Picasso - Wikipedia Picasso Quotes | Art Quotes by Pablo Picasso | Art Therapy (arttherapyblog.com) Activities: 1. Create a Picasso face. Use paint, magazine pictures, cut up construction paper or clay. 2. Make collage art. 3. Picasso color page - coloring-page.jpg (377×480) (artsycraftsymom.com) 4. Picasso’s Blue period was during a sad time in his life. His Rose Period was during a time filled with joy and love. His art reflects his moods in colors, subjects and style. Create your own Blue Period/ Rose Period paintings. Or find your own mood and paint according to that. 5. Watch this video about Picasso - (2) 10 Amazing Facts about Spanish Artist Pablo Picasso - YouTube Art Appreciation – Pablo Picasso Thank you for downloading the Pablo Picasso Study Guide. -

The Auditorium Theatre Celebrates 50Th Anniversary of Their Grand Re

10/12/2017 Auditorium Theatre One-Night-Only Performance Honoring the Theatre's Past, Present, Future View in browser 50 E Congress Pkwy Lily Oberman Chicago, IL 312.341.2331 (office) | 973.699.5312 (cell) AuditoriumTheatre.org [email protected] Release date: October 5, 2017 THE AUDITORIUM THEATRE CELEBRATES 50th ANNIVERSARY OF THEIR GRAND RE-OPENING WITH ONE-NIGHT-ONLY PERFORMANCE FEATURING PREMIER DANCERS FROM TOP COMPANIES AROUND THE WORLD THE EVENING INCLUDES PERFORMANCES BY DANCERS FROM ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER, AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE, DUTCH NATIONAL BALLET, THE JOFFREY BALLET, NEW YORK CITY BALLET, THE WASHINGTON BALLET, AND FINALISTS FROM YOUTH AMERICA GRAND PRIX A Golden Celebration of Dance – November 12, 2017 On November 12, 2017, the Auditorium Theatre, The Theatre for the People, commemorates the 50th anniversary of its grand re-opening with A Golden Celebration of Dance, a one-night-only mixed repertory program featuring dancers from the world’s premier dance companies: Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, American Ballet Theatre, Dutch National Ballet, Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg, Hubbard Street Dance Chicago, The Joffrey Ballet, MOMIX, New York City Ballet, Parsons Dance, The Suzanne Farrell Ballet, and The Washington http://tracking.wordfly.com/view/?sid=NjUzXzQ4NTRfMjc3ODA2XzY5NTk&l=4d2b8dea-61af-e711-8416-e41f1345a486&utm_source=wordfly&utm_me… 1/5 10/12/2017 Auditorium Theatre Ballet. In addition, the evening will feature special performances by finalists from the Youth America Grand Prix, the next generation of great dancers. In 1941, the Auditorium Theatre closed its doors to the public in the wake of the Great Depression. Aside from when it was used as a servicemen’s center during World War II, the theatre sat unused and in disrepair, until a 7-year-long fundraising campaign – led by Beatrice Spachner and the Auditorium Theatre Council – covered the costs of theatre renovation, culminating with a grand re-opening on October 31, 1967. -

The Nightmare Before Christmas

Featuring the Chicago Philharmonic View in browser 50 E Congress Pkwy Lily Oberman Chicago, IL 312.341.2331 (office) | 973.699.5312 (cell) AuditoriumTheatre.org [email protected] Release date: July 17, 2018 DISNEY IN CONCERT: TIM BURTON’S THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS COMES TO THE AUDITORIUM THEATRE ON OCTOBER 31 TICKETS ON SALE JULY 27 AT NOON COMMEMORATING THE 25th ANNIVERSARY OF THE CLASSIC FILM Chicago Philharmonic Performs Danny Elfman’s Renowned Score Live to Film Disney in Concert: Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas – October 31, 2018 (Chicago, IL) – Jack Skellington and the residents of Halloween Town pay a visit to Chicago on October 31, 2018, when Disney in Concert: Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas comes to the Auditorium Theatre. Tickets go on sale Friday, July 27 at noon and will be available online at AuditoriumTheatre.org, by phone at 312.341.2300, or in person at the Auditorium Theatre Box Office (50 E Congress Pkwy). Tickets start at $30. Tickets are also on sale now as part of the Auditorium's American Music Series subscription and for groups of 10 or more people. The Halloween screening commemorates the 25th anniversary of Tim Burton's stop-motion masterpiece and features the Chicago Philharmonic performing Danny Elfman's beloved score. Attendees are encouraged to dress in costume and celebrate Halloween in the Auditorium Theatre lobby. "We are beyond thrilled to celebrate the 25th anniversary of this classic film on our historic stage with the acclaimed musicians of the Chicago Philharmonic, right on Halloween!" says C.J. -

Ate9 Dance Company (With Glenn

Featuring Ate9 Dance Company, Deeply Rooted Dance Theater, View in browser and Visceral Dance Chicago 50 E Congress Pkwy (50 E Ida B. Wells Dr) Lily Oberman Chicago, IL 312.341.2331 (office) | 973.699.5312 (cell) AuditoriumTheatre.org [email protected] Release date: October 10, 2018 ATE9 DANCE COMPANY (WITH GLENN KOTCHE OF WILCO), DEEPLY ROOTED DANCE THEATER, AND VISCERAL DANCE CHICAGO PERFORM AT THE AUDITORIUM THEATRE AS PART OF THE “MADE IN CHICAGO” 312 DANCE SERIES ON NOVEMBER 16 AN EVENING OF INNOVATIVE CONTEMPORARY DANCE Ate9 Dance Company/Deeply Rooted Dance Theater/Visceral Dance Chicago on November 16, 2018 (CHICAGO, IL) – On Friday, November 16, three groundbreaking contemporary dance companies perform on the Auditorium Theatre’s landmark stage in the “Made in Chicago” 312 Dance Series. The evening features Ate9 Dance Company, performing the work calling glenn with live music from Chicago-based percussionist Glenn Kotche (Wilco); Deeply Rooted Dance Theater, performing Kevin Iega Jeff’s Church of Nations, Kevin Iega Jeff and Gary Abbott’s Heaven, and Nicole Clarke-Springer’s Until Lambs Become Lions; and Visceral Dance Chicago, performing company founder Nick Pupillo’s Soft Spoken. “We are thrilled to feature these three innovative companies as we open our 2018-19 ‘Made in Chicago’ 312 Dance Series,” says Rachel Freund, Interim Chief Executive Officer of the Auditorium Theatre. “This evening will highlight the creativity of these distinct companies and showcase the breadth of contemporary dance styles that we present on our historic stage.” The Los Angeles-based Ate9 Dance Company makes its Auditorium Theatre debut with calling glenn (2017), created by company founder and artistic director Danielle Agami in collaboration with Chicagoan Glenn Kotche. -

Twyla Tharp 50 Anniversary Tour

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Jill Evans La Penna August 27, 2015 James Juliano SHOUT Marketing & Media Relations [email protected] • [email protected] (312) 533-9119 • (773) 852-0506 THE AUDITORIUM THEATRE PROUDLY PRESENTS TWYLA THARP’S 50TH ANNIVERSARY TOUR IN CHICAGO, NOVEMBER 5 – 8 Two New Works Commissioned by the Auditorium Theatre and Ravinia Festival Along With The Joyce Theater, The Kennedy Center, TITAS/AT&T Performing Arts Center and the Wallis Anneberg Center for the Performing Arts are the Centerpiece of the National Celebration of Tharp’s 50th Anniversary. CHICAGO, IL — The Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University presents Twyla Tharp – 50th Anniversary Tour including two Chicago premieres, “Preludes and Fugues” and “Yowzie” November 5 – 8, at the historic Auditorium Theatre, 50 E. Congress Parkway. In a momentous co-commission with Ravinia Festival, as well as four other dance presenters in four other cities, the Auditorium is thrilled to present these two new works by world-renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp. The performance schedule is Thursday, Nov. 5 – Saturday, Nov. 7 at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, Nov. 8 at 2 p.m. Tickets are priced $33 - $103 and are available online at AuditoriumTheatre.org by calling (312) 341-2300 or in-person at the Auditorium Theatre’s Box Office, 50 E. Congress Parkway. Subscriptions for the Auditorium Theatre’s 2015 - 2016 season and discounted tickets for groups of 10 or more are also on sale. For more information visit AuditoriumTheatre.org. “We are proud to be a part of the national celebration of Twyla Tharp and her 50th Anniversary Tour, not only as a presenter but also as a co-commissioner of these two premieres. -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor. -

Explore Our Virtual Program

20|21 MICHAEL WEBER JEANNIE LUKOW Artistic Director Executive Director presents Featuring ANTHONY COURSER, PAM CHERMANSKY, CROSBY SANDOVAL, JAY TORRENCE, LEAH URZENDOWSKI & RYAN WALTERS Written by JAY TORRENCE Direction by HALENA KAYS This production was filmed during Porchlight Music Theatre’s premiere with The Ruffians at the Ruth Page Center for the Arts, December 13 - 27, 2019. Understudies for 2019 Production Nellie Reed: KAITLYN ANDREWS Henry Gilfoil/Eddie Foy: DAVE HONIGMAN Fancy Clown: JAY TORRENCE Faerie Queen/Robert Murray: RAWSON VINT Choreography by LEAH URZENDOWSKI Additional 2019 Choreography by ARIEL ETANA TRIUNFO Lighting Design MAGGIE FULLILOVE-NUGENT Original Scenic & Costume Design LIZZIE BRACKEN Scenic Design JEFF KMIEC Costume Design BILL MOREY Sound Design MIKE TUTAJ Associate Sound Design ROBERT HORNBOSTEL Original Properties Design MAGGIE FULLILOVE-NUGENT & LIZZIE BRACKEN Properties Master CAITLIN McCARTHY Original Associate Properties Design ARCHER CURRY Technical Direction BEK LAMBRECHT Production Stage Management JUSTINE B. PALMISANO Production Management SAM MORYOUSSEF & ALEX RHYAN Video Production MARTY HIGGENBOTHAM/THE STAGE CHANNEL The following artists significantly contributed to this performance and the play’s creation: Lizzie Bracken (set design, costume design, prop design), Dan Broberg (set design), Maggie Fullilove-Nugent (lighting design), Leah Urzendowski (choreography) & Mike Tutaj (sound design). The original 2011 cast included Anthony Courser, Dean Evans, Molly Plunk, Jay Torrence, Leah Urzendowski & Ryan Walters This performance runs 100 minutes without intermission. Please be aware this play contains flashing lights and some moments that may trigger an adverse reaction with sudden loud noises and sounds of violence. Porchlight Music Theatre acknowledges the generosity of Allstate, the Bayless Family Foundation, DCASE Chicago, the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, James P. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 8, 2017 CONTACT: Mayor's Press

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 8, 2017 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR EMANUEL CELEBRATES THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE CHICAGO PICASSO ON DALEY PLAZA Everyone’s Picasso commemorates the 1967 unveiling of Picasso’s first large-scale civic sculpture in America Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) today celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Chicago Picasso at Daley Plaza. Called Everyone’s Picasso, the ceremony restaged the original 1967 unveiling of the sculpture. The Chicago Picasso is considered to be artist Pablo Picasso’s first large-scale civic sculpture in America. “Chicago’s Picasso exemplifies the lasting legacy public art has on the fabric of our city,” said Mayor Rahm Emanuel. “A fitting anniversary as part of the 2017 Year of Public Art, the Picasso has inspired artists, sculptors, painters and poets to make the City of Chicago a global hub for culture and art.” While the Picasso attracted mixed reviews when it was unveiled on August 15, 1967, it has since become an enduring influence on Chicago’s public art. It has been featured in popular films like The Blues Brothers, The Fugitive, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Now a beloved symbol of Chicago, the Picasso is central to hundreds of events in Daley Plaza, including creative arts performances and farmers markets. “Chicago’s reputation as an innovator and leader in the presentation of public art continues to this day,” said DCASE Commissioner Mark Kelly. “The Picasso helped spark Chicago’s legacy of public art and has inspired artists across the world for decades.” The commemoration ceremony, called Everyone’s Picasso, was conceived by artist and historian Paul Durica. -

TIM BURTON's the NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS on HALLOWEEN and NOVEMBER 1 Featuring the Chicago Philharmonic Performing Danny Elfman's Classic Score Live to Film

With the Chicago Philharmonic on the Historic Landmark Stage View in browser 50 E Ida B Wells Dr Lily Oberman Chicago, IL Auditorium Theatre AuditoriumTheatre.org 312.341.2331 (office) | 973.699.5312 (cell) [email protected] Release date: September 17, 2019 THE AUDITORIUM THEATRE PRESENTS DISNEY IN CONCERT: TIM BURTON'S THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS ON HALLOWEEN AND NOVEMBER 1 Featuring the Chicago Philharmonic Performing Danny Elfman's Classic Score Live to Film Halloween Activities, Including Trick-or-Treating and a Costume Contest, Hosted in the Theatre's Historic Lobbies Before the Show and During Intermission (CHICAGO, IL) The live concert experience of Tim Burton's The Nightmare Before Christmas returns to the Auditorium Theatre for the second year for two special Halloween screenings on October 31 and November 1. The Chicago Philharmonic brings the film to life as they perform Danny Elfman's classic score, including iconic songs like "This Is Halloween" and "Jack's Lament." "As we celebrate the 130th anniversary of the Auditorium, we are excited to establish new traditions like the annual showing of The Nightmare Before Christmas here at the theatre," says C.J. Dillon, Auditorium Theatre Chief Programming Officer. "It is an unforgettable experience to hear the songs and music from this beloved movie performed live on the Auditorium Theatre's stage alongside the film. We invite all of Chicago to join us for this unique Halloween celebration!" Visitors are encouraged to arrive early to participate in Halloween activities in the theatre's historic (and perhaps even haunted!) historic lobby spaces. Guests can go trick-or-treating around the theatre; stop by and create a drawing at a coloring station; and pose for photos in front of an Auditorium-themed backdrop with special Nightmare props, including a life-sized Jack Skellington. -

Culturalupdate Volume XXVIII—Issue IV New / News Arts / Museums ♦Punch Bowl Social, 310 N

CONCIERGE UNLIMITED INTERNATIONAL April 2018 culturalupdate Volume XXVIII—Issue IV new / news arts / museums ♦Punch Bowl Social, 310 N. Green Street Opens 3/23 Arte Diseño Xicágo National Museum of Mexican Art Welcome to the trendy, new, Fulton 14 Modern Japanese Portraits Art Institute Chicago Market sports bar for hungry 27 Volta Photo Art Institute Chicago customers and game players alike. 28 Picture Fiction: Kenneth Josephson MCA Chicago Sporting a 30,000 square-foot play and Contemporary Photography area, Punch Bowl Social has booze, 28 John Akomfrah: Three Films SF Museum of Modern Art a bowling alley, food, and more. 31 Helen Frankenthaler Prints: Art Institute Chicago Their cocktails are themed to match The Romance of a New Medium each city location; specially there’s a through punch named after the Stanley Cup to honor the Blackhawks. 1 We are here MCA Chicago 8 Felix MCA Chicago Stefani Prime, 6755 N Cicero Ave ♦ 15 New York on Ice Museum of the City NYC 12/31 Saturday Night Live, The Experience Museum Broadcast Communications Recently opened in Lincolnwood, Free Admission to Museums Stefani Prime, an Italian restaurant Art Institute Chicago* All Thursdays after 5pm aims to bring “prime” steak, seafood and Italian food options to Chicago History Museum* All Tuesday’s after 12:30pm the Chicago suburbs. DuSable Museum* 3,10,17,24 * Available to Illinois residents only. Must show valid ID. Contact your CUI Concierge to secure your VIP Reservations! ballet / dance 6-8 Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg David H. Koch Theatre NYC we recommend 7 Springfive Harris Theatre ♦Pretty Woman: The Musical 18-19 Youth America Grand Prix David H. -

Performing Arts Venue Relief Grants Program � Round 1 & 2 Grantees �

Performing Arts Venue Relief Grants Program � Round 1 & 2 Grantees � A Red Orchid Theatre The Gift Theatre Stage 773 Adventure Stage Chicago Goodman Theatre Steppenwolf Theatre Aguijon Theater Company Green Mill Company Aloft Dance Harris Theater for Music and Subterranean Andy's Dance Thalia Hall The Annoyance The Hideout Theater Wit Artango Bar and Steakhouse Hungry Brain Tight Five Productions Auditorium Theatre The Hyde Room Timeline Theatre Avondale Music Hall Hydrate Nightclub The Tonic Room Beat Kitchen The Jazz Showcase Trap Door Theatre Beauty Bar Lifeline Theatre Trickery Berlin Lincoln Hall The Underground Beverly Arts Center Links Hall The Vig Black Ensemble Theater Local 83 Victory Gardens Theatre Chicago Children's Theatre Lookingglass Theatre Watra Nightclub Chicago Chop Shop Company West Loop Entertainment Chicago Dramatists Martyrs' Windy City Playhouse Chicago Magic Lounge Metro Smartbar Zanies Comedy Club Chicago Shakespeare Theater The Miracle Center Chicago Symphony Orchestra The Neo-Futurists Chopin Theatre Newport Theater City Lit Theater Nocturne Cobra Lounge Old Town School of Folk Cole's Bar Music The Comedy Clubhouse Otherworld Theatre ComedySportz Company Concord Music Hall Owl Bar Constellation Arts The Patio Theater Copernicus Center persona Corn Productions Prysm Dance Center of Columbia Public Media Institute College Chicago Radius Davenport's Piano Bar and Raven Theatre Company Cabaret Redtwist Theatre The Den Theatre Reggie's Music Club Dorian's The Revival Drunk Shakespeare Rosa's Lounge Elastic Arts Rufuge Live! The Empty Bottle Schubas Epiphany Center for the Arts Silk Road Rising Escape Artistry Silvie's Escape Artistry II Sleeping Village eta Creative Arts Foundation Slippery Slope . -

Bolshoi Ballet

Photo by Damir Yusupov BOLSHOI CHICAGOBALLET WEEKEND | JUNE 12-14, 2020 HOSTED BY THE MUSEUM OF RUSSIAN ART AND NORTHROP, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Join The Museum of Russian Art and Northrop for an evening Bolshoi Ballet performance of Swan Lake, as the piece de resistance of a fantastic weekend in Chicago! This exclusive excursion also features a private tour of The Art Institute of Chicago, learning about iconic architecture aboard a cruise on the Chicago River, and incredible cuisine and accommodations. This will be a weekend in Chicago to remember! FRIDAY, JUNE 12 Your afternoon is free to explore Chicago or visit the iconic shops along Depart Minneapolis/St. Paul Airport at 9:07am on your flight to Chicago. Michigan Avenue. Arrive at Chicago O’Hare Airport at 10:31am where you will be met by our representatives to start your adventure. You will start off your afternoon with This evening you will have a pre-ballet dinner at Russian Tea Time lunch at Terzo Piano located at the Art Institute of Chicago. The restaurant Restaurant. Centrally located in heart of Chicago’s Downtown, Russian features the signature cuisine of Chef Tony Mantuano who has been Tea Time has earned the distinction of being one of Chicago’s culinary delighting Chicagoans for years at the four star Italian restaurant Spiaggia. “landmarks.” Russian Tea Time offers a variety of dishes from the diverse regions of the former Soviet Union Republics. Continue your afternoon with a private tour at the Art Institute of Chicago. The Art Institute of Chicago is one of the oldest and largest art Following dinner, enjoy a Bolshoi Ballet performance of Swan Lake at museums in the United States.