ABORIGINAL MENTAL HEALTH: a FRAMEWORK for ALBERTA Healthy Aboriginal People in Healthy Communities ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pincher Creek, Health Data and Summary, 4Th Edition

Alberta Health Primary, Community and Indigenous Health Community Profile: Pincher Creek Health Data and Summary 4th Edition, December 2019 Alberta Health December 2019 Community Profile: Pincher Creek Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. i Community Profile Summary .............................................................................................................. iii Zone Level Information ........................................................................................................................... 1 Map of Alberta Health Services South Zone ............................................................................................. 2 Population Health Indicators ...................................................................................................................... 3 Table 1.1 Zone versus Alberta Population Covered as at March 31, 2018 .............................................. 3 Table 1.2 Health Status Indicators for Zone versus Alberta Residents, 2013 and 2014 (Body Mass Index, Physical Activity, Smoking, Self-Perceived Mental Health)……………………………...............3 Table 1.3 Zone versus Alberta Infant Mortality Rates (per 1,000 live births), Years 2016 – 2018…….. ..4 Community Mental Health ........................................................................................................................... 5 Table 1.4 Zone versus Alberta Community Mental -

Current Approaches to Aboriginal Youth Suicide Prevention

CMHRU Working Paper 14. Current Approaches to Aboriginal Youth Suicide Prevention Laurence J. Kirmayer Sarah-Louise Fraser Virginia Fauras Rob Whitley Culture & Mental Health Research Unit Institute of Community & Family Psychiatry Jewish General Hospital 4333 Cote Ste Catherine Rd. Montreal, Quebec H3T 1E4 Tel: 514-340-7549 Fax: 514-340-7503 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface & Acknowledgment ................................................................................... 6 Summary .................................................................................................................. 7 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 9 1.1. Objectives 1.2. Outline 1.3. Methods 1.4. Terminology 1.5. Levels and Targets of Intervention 2. Background ........................................................................................................ 12 2.1. Patterns and Prevalence of Suicide 2.1.1 Global Patterns of Suicide 2.1.2 Patterns of Suicide in Canada 2.1.3 Patterns of Suicide among Indigenous People Outside Canada 2.2. Causes of Suicide: Risk and Protective Factors 2.2.1 General Risk Factors 2.2.2 Gender Related Risk Factors 2.2.3 Risk factors Specific to Adolescents and Young Adults 2.2.4 Protective Factors 2.2.5 Summary of Risk Factors 2.3. Approaches to Suicide Prevention 2.4. Previous Reports on Aboriginal Youth Suicide Prevention 3. Suicide Prevention Programs and Interventions ................................................ 27 3.1. Education and Awareness Programs 3.1.1. School-based Programs 3.1.1.1 Agir Ensemble pour Prévenir le Suicide chez les jeunes 3.1.1.2 Psychoeducation in Belgium 3.1.1.3 Lifelines New Jersey 3.1.1.4 The South Elgin High School Suicide Prevention Project 3.1.1.5 SOS Suicide Prevention Program 3.1.1.6 Raising Awareness of Personal Power 3.1.1.7 Analysis 3.1.2. -

April 4, 2012

April 4, 2012 CURRICULUM VITAE Judith C. Kulig, RN, DNSc University of Lethbridge Faculty of Health Sciences 4401 University Drive Lethbridge, AB T1K 3M4 (403) 382-7119 (403) 329-2668 (fax) [email protected] web page: http://people.uleth.ca/~kulig/ CURRENT STATUS Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Lethbridge University Scholar, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Lethbridge EDUCATION 1991 DNSc Doctor of Nursing Science Department of Mental Health, Community and Administrative Nursing, University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), San Francisco, CA, USA Dissertation Title: Cambodian Refugee Women's Role Changes and Family Planning Use 1984 MSN Master of Science in Nursing University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Thesis Title: Cultural Beliefs and Knowledge on Sexuality Among Cambodian Refugee Women 1983 BScN Bachelor of Science in Nursing University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB 1978 RN Registered Nurse Medicine Hat College, Medicine Hat, AB Language Training June - August 1989 Southeast Asian Summer Institute, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Language: KHMER, Recipient: Tuition waiver and stipend April 4, 2012 Judith C. Kulig 2 PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS 2008 – ongoing Aboriginal Nurses Association of Canada 1999 - ongoing Canadian Rural Health Research Society 1997 - 2004 Community Development Society 1992 – 2007 Western Regional Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing 1985 - 2005 Canadian Nurses Foundation 1984 - ongoing Beta Mu Chapter, Sigma Theta Tau 1978 - ongoing College & Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta -

PATTON-DISSERTATION-2021.Pdf (2.899Mb)

CON(TRA)CEPTS OF CARE: SOUTHERN ALBERTA BIRTH CONTROL CENTRES & REPRODUCTIVE HEALTHCARE, 1969-1979 A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy In the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan By KARISSA ROBYN PATTON © Copyright Karissa Robyn Patton, February 2021. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise noted, copyright of the material in this thesis belongs to the author. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the History Department 5A5, 9 Campus Dr #619 University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 4L3 Canada OR The Dean of College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan 116 Thorvaldson Building, 110 Science Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5C9 Canada i ABSTRACT In 1969, as the government of Alberta rolled out their provincial healthcare policy the Canadian government decriminalized contraception and abortions approved by Therapeutic Abortion Committees. -

Aboriginal Diabetes Projects in Canada

Aboriginal Diabetes Projects in Canada Province Name Address Activities Alberta Aboriginal Diabetes 801-1 Avenue South • Individual Sessions Prevention and Lethbridge Alberta T1J 4L5 • Group Sessions Management • Pregnancy Clinics Program Tel: 403-388-6675 • In-patient support • Insulin Initiation Program • Diabetes and Heart Classes • Blood Glucose Screening • Community Presentations • Walking Groups • Community Kitchen • Grocery Store Tours Aboriginal Diabetes 204-Anderson Hall • Organized Walks Wellness Program- 10959-102 Street • Nutrition Programs Capital Health Edmonton, Alberta • School Diabetes Programs • Awareness Promotion Tel: 780-477-4512 • Traditional Herb/Medicine Workshop • Glucose monitoring Description: 1 or 3 Day Basic Diabetes Education Program provides a holistic and cultural program for people living with Diabetes, offers the choice of traditional and /or western ways to wellness, and assists individuals to learn how to balance mind, body , emotion and spirit. Alexis First Nation Alexis First Nation • School Diabetes Program PO Box 39 • Awareness Promotion Glenevis, Alberta • Foot Care Clinics • School Breakfast/Lunch Program Tel: 780-967-2591 • Pre-Natal Education • Annual Diabetes Week Description: On-going monitoring is done on a one to one basis Atikameg Health Atikameg Health Centre • Organized Walks Centre Box 210 • Nutrition Program Atikameg Alberta • Awareness Promotion • Traditional Herb/Medicine Workshops Tel: 780-767-3941 • Foot Care Clinic • Glucose Monitoring • Pre-Natal Education Description: No information -

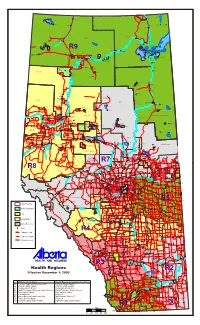

R9 R7 R8 R3 R1 R2 R4 R5 R6

Charles Lake I.R. 225 Fitzgerald Indian Cabins Jackfish Point I.R. 214 Bistcho Lake Cornwall Lake Collin Lake I.R. 213 I.R. 224 I.R. 223 Steen River Hay Camp I.D. 24 M.D. 23 Peace Point Upper Hay River Meander River I.R. 212 Carlson Landing Amber River I.R. 211 Sand Point Sweet Grass Landing I.R. 221 Habay Devil’s Gate I.R. 220 Zama Lake Allison Bay Hay Lake I.R. 210 I.R. 219 I.R. 209 R9 Dog Head I.R. 218 Fort Chipewyan Chateh Chipewyan I.R. 201A Garden Creek Quatre Fourches Little Fishery Chipewyan I.R. 201B Fifth Meridian Jean D’Or Prairie Child Lake Beaver Ranch High Level I.R. 215 Chipewyan Rainbow Lake I.R. 164A Rocky Lane I.R. 163B I.R. 201 Boyer Beaver Ranch Chipewyan I.R. 201C I.R. 163A Fox Lake Jackfish I.R. 164 Fox Lake Old Fort Chipewyan I.R. 201D Beaver Ranch I.R. 162 I.R. 217 Chipewyan I.R. 201E Bushe River North Vermilion Settlement I.R. 163 I.R. 207 Fort Vermilion Little Red River I.R. 173B Fort Vermilion Vermilion Chutes Embarras La Crete Buffalo Head Prairie Tall Cree Chipewyan I.R. 173A I.R. 201F Paddle Prairie Metis Settlement Chipewyan Paddle Prairie I.R. 201G M.D. 22 Tall Cree I.R. 173 Carcajou I.R. 187 Keg River Carcajou Wadlin Lake I.R. 173C Namur River I.R. 174A Bitumount Namur River I.R. 174B Fort MacKay Fort McKay I.R. 174 Hotchkiss Mildred Lake Notikewin Chipewyan Lake Manning M.D. -

Crowsnest Pass, Health Data and Summary, 4Th Edition

Alberta Health Primary, Community and Indigenous Health Community Profile: Crowsnest Pass Health Data and Summary 4th Edition, December 2019 Alberta Health December 2019 Community Profile: Crowsnest Pass Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. i Community Profile Summary .............................................................................................................. iii Zone Level Information ........................................................................................................................... 1 Map of Alberta Health Services South Zone ............................................................................................. 2 Population Health Indicators ...................................................................................................................... 3 Table 1.1 Zone versus Alberta Population Covered as at March 31, 2018 .............................................. 3 Table 1.2 Health Status Indicators for Zone versus Alberta Residents, 2013 and 2014 (Body Mass Index, Physical Activity, Smoking, Self-Perceived Mental Health)……………………………...............3 Table 1.3 Zone versus Alberta Infant Mortality Rates (per 1,000 live births), Years 2016 – 2018…….. ..4 Community Mental Health ........................................................................................................................... 5 Table 1.4 Zone versus Alberta Community -

Revised: 05/10 Lethbridge Guide for Help

Revised: 05/10 Lethbridge Guide for Help Are you new to Lethbridge? Has your life taken a turn? Are you in need of comfort and support? Remember the community of Lethbridge is committed to assisting residents whenever possible. The City of Lethbridge has developed this booklet for members of its community to help assist them when they are searching for a place to sleep, something to eat, someone to talk to; if you need a place to get clothes, a place to dry out, a place to relax; if you want to see a doctor, a lawyer or a counsellor, or simply want to change your situation. “Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.” Community LINKS is a non-profit organization that provides information, referrals and connections to government, health and social services, a calendar of events, as well as business links. Phone: 403 328-LINK (5465) Email: [email protected] Website: www.community-links.ca 2 Bringing Lethbridge Home Table of Contents Lethbridge Emergency Numbers ................................4 Help Numbers ............................................................5 Alcohol & Drugs ..........................................................8 Child & Family Support .............................................14 Clothing & Furniture...................................................23 Counselling & Community Support...........................24 Crisis & Outreach Support ........................................32 Education..................................................................36 Employment & Training ............................................43 -

Job Fair & First Nations, Metis and Inuit Resource Fair 2008 Participants List March 12, 2008

Job Fair & First Nations, Metis and Inuit Resource Fair 2008 Participants List March 12, 2008 FIRST NATIONS, METIS & INUIT (FNMI) RESOURCE FAIR Wednesday, March 12th Atrium, University Hall Booths: 9:30am - 3:30pm Programs, Community and Support Services for FNMI students Presented by Career & Employment Services 1st Choice Savings & Credit Union Public Service Commission, HR - Syncrude Canada Ltd. AB/NWT COE Newnes/Mcgehee Imperial Tobacco Canada Canada Revenue Agency TD Canada Trust AB Employment, Immigration and Real Canadian Superstore Community Savings Industry Canada Safeway Limited Teamworks Career & Employment Institute of Chartered Accountants of Royal Bank of Canada Centre/Select Recruiting Alberta Canadian Security Intelligence Service Convergys Agriculture and Food Council Scotiabank Totem Building Supplies Ltd. Interior Health Authority Canon Canada David Thompson Health Region Agrium Inc. Sherwin-Williams Canada, Inc Town of High River Kainaiwa Children's Services Canadian Food Inspection Agency Devon Canada Corporation Corporation Royal Canadian Mounted Police TransCanada AltaGas Canadian Forces Recruiting Centre Discount Car and Truck Rentals Kids Cancer Care Foundation of Royal Canadian Mounted Police United Farmers of Alberta Alberta Canadian Pacific Railway Edward Jones Investments AMEC Earth & Environmental Ryder System, Inc. University First Class Painters LaFarge Canada Inc. Canadian Security Intelligence Service Elk Valley Coal ATB Financial Scotiabank Value Village -

Continuing Care in Indigenous Communities Guidebook

Continuing Care in Indigenous Communities GUIDEBOOK Note: This guidebook will be reviewed and updated periodically. If you printed this document from an online source it is considered valid only on the day that it was printed. After this date, please refer back to the online document to ensure that you are using the most up to date version. Revised: July 30, 2021 The Blood Tribe’s Journey to Continuing Care Written by Randal Bell, Provincial Initiatives Consultant-Indigenous Populations; Community, Seniors, Addiction and Mental Health The journey to the Kainai Continuing Care Centre (KCCC) was a long rocky road, full of confusing twists and turns. A few times I thought I had gotten lost on the back roads and pondered turning back. My journey to the KCCC was a good metaphor for the community’s long journey towards continuing care. The Blood Tribe had set out on a path to establish their own continuing care centre a long time ago and it would be a long, arduous and difficult journey. In 1928, the Blood Indian Hospital was built in Cardston and was one of six hospitals built and owned by the federal Department of Health and Welfare. In 1957, the new Cardston Clinic opened its doors but the physicians’ outpatient clinics were held in the hospital until 1974. After 1974, the outpatient clinics were moved to the Shot Both Sides building at Standoff, on the Blood Reserve. Eventually the Department of Health and Welfare moved to close the six on-reserve hospitals. Tribal leadership authorized the Blood Tribe Department of Health Inc. -

CQB Decision Elder Advocates and James Darwish V Government of Alberta Et Al August 2008

Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta Citation: Elder Advocates of Alberta Society v. Alberta, ABQB 490 Date: 20080814 Docket: 0503 13196 Registry: Edmonton Between: Elder Advocates of Alberta Society and James O. Darwish, Personal Representative of the Estate of Johanna H. Darwish, Deceased Plaintiffs - and - Her Majesty the Queen In Right of Alberta, Aspen Regional Health Authority, Calgary Health Region, Capital Health, Chinook Regional Health Authority, East Central Health, Northern Lights Health Region, Palliser Health Region, Peace Country Health Defendants _______________________________________________________ Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Madam Justice S.J. Greckol _______________________________________________________ I. Introduction........................................................Page: 3 II. Legislation.........................................................Page: 5 A. Class Proceedings Legislation....................................Page: 5 B. Legislative Scheme for the Provision of Health Care Services. Page: 8 1. Federal Health Legislation.................................Page: 9 2. Alberta Legislation - Alberta Health Care Insurance Act and Subordinate Regulations. ...........................................Page: 9 3. Alberta Legislation - Nursing Homes Act and Subordinate Regulations .....................................................Page: 12 Page: 2 4. Alberta Legislation - Hospitals Act and Subordinate Regulations .....................................................Page: 17 5. Alberta Legislation - Regional -

A - Z PIA Registry the Following Table Lists All Privacy Impact Assessments (PIA) That the OIPC Has Accepted for Which There Are Summaries Available

A - Z PIA Registry The following table lists all Privacy Impact Assessments (PIA) that the OIPC has accepted for which there are summaries available. Not all PIAs accepted by the OIPC include summaries. If you would like a copy of a PIA summary from past years, please contact the office at (780) 422-6860 or email [email protected]. The table does not include summaries for PIAs accepted by the OIPC for the following programs: • Alberta Netcare PIA Pharmacies Listing • Alberta Netcare PIA Physician Listing • Physician Office System Program (POSP) PIA Listing • Alberta Pharmacy Practice Models Initiative (PPMI) Listing • Mihealth Physician PIA Listing Public Body or Custodian PIA Project Title Legislation Acceptance Date OIPC File # Abounaja, Dr. Muadh; Pineridge TELUS Health Solutions (Wolf EMR) HIA April 2, 2015 000092 Doctors Office encompassing Organizational Practices and Reporting on Information Management Systems and/or External Services and PCN Participation: Mosaic PCN. Adams, Dr. Stewart; Metelitsa, Dr. Optimed Accuro EMR System HIA January 13, 2016 001745 Andrei; Devani, Dr. Alim; Prajapati, encompassing Netcare access Dr. Vimal; Institute for Skin Advancement Inc. Adams, Dr. Stewart; Woolner, Dr. Outsourced Transcription Services HIA June 4, 2008 H2085 Derek; Hackett, Dr. Sharon; Dermatology Associates Advanced Education and Dr. Gary McPherson Leadership FOIP October 26, 2011 F5884 Technology Scholarship Advanced Education and Alberta Advanced Education's Alberta FOIP October 17, 2005 F3276 Technology Advanced Education's