PATTON-DISSERTATION-2021.Pdf (2.899Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report for the LETHBRIDGE JUDICIAL DISTRICT January 2010

THE ALBERTA LEGAL SERVICES MAPPING PROJECT Report for the LETHBRIDGE JUDICIAL DISTRICT January 2010 Glynnis A. Lieb PhD (cand.) Stephanie Abel MA Canadian Forum on Civil Justice 110 Law Centre, University of Alberta Edmonton AB T6G 2H5 Ph. (780) 492- 2513 Fax (780) 492-6181 Acknowledgements The Alberta Legal Services Mapping Project is a collaborative undertaking made possible by the generous contributions of many Albertans. We are grateful to the Alberta Law Foundation and Alberta Justice for the funding that makes this project possible. The project is guided by Research Directors representing the Alberta Law Foundation, Alberta Justice, Calgary Legal Guidance, the Canadian Forum on Civil Justice, Edmonton Community Legal Centre, Legal Aid Alberta, and the Alberta Ministry of Solicitor General and Public Security. We are also indebted to our Advisory Committee which is made up of a wide group of stakeholders, and to the service providers who acted as Key Contacts in the Lethbridge Judicial District for their valuable input and support. We also thank all members of the Research Team and everyone who has dedicated their time as a research participant in order to make this report possible. Disclaimer This report and its appendices have been prepared by the Canadian Forum on Civil Justice and the Alberta Legal Services Mapping Team and represent the independent and objective recording and summarization of input received from stakeholders, service providers and members of the public. Any opinions, interpretations, conclusions or recommendations contained within this document are those of the writers, and may or may not coincide with those of the Alberta Law Foundation or other members of the Research Director Committee. -

Report of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police, 1914

5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1915 REPORT OF THE ROYAL NORTHWEST MOUNTED POLICE 1914 PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT OTTAWA. PRINTED BY J. ok L. TACHE, PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1915 [No. 28—1915.] 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1915 To Field Marshal, His lloyal Highness the Duke of Connaught and of Strothearn, K.G., K.T.. K.P., etc., etc., etc.. Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Dominion of Canada. May it Please Your Royal Highness : The undersigned has the honour to present to Your Royal Highness the Annual Report of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police for the year 1914. Respectfully submitted, R. L. BORDEX, President of the Council. December 2, 1914. 28—n 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1915 TABLE OF CONTENTS. PART i. Page. Commissioner's Report, 1014 7 Appendices to the above. Appendix A.-—Superintendent J. O. Wilson, Lethbridge 27 ( B.— Superintendent J. A. McGibbon, Regina District.. l » C.—Superintendent W. H. Routledge, Prince Albert >'>7 D.—Superintendent C. Starnes, Maeleod 81 E.—Superintendent T. A. Wroughton, Edmonton 100 F.—Superintendent F. J. Horrigan, Maple Creek Ill G.—Superintendent A. E. C. McDonell, Athabaska Landing 125 H—Superintendent C. H. West, Battleford 137 J.—Inspector G. S. Worsley, Calgary 152 K.—Inspector R. S. Knight, ''Depot" Division, Regina.. .. .. .. 170 L.—Surgeon G. P. Bell, Regina 178 M.—Veterinary Surgeon J. F. Burnett, Regina 180 N.—Inspector J. W. Phillips, Mackenzie River Sub-district. ..... 1S2 O.-—Inspector C. Junget, Mine disaster at Hillcrest. -

Legislative Assembly of Alberta Title

February 28, 1996 Alberta Hansard 303 Legislative Assembly of Alberta DR. WEST: May I, Mr. Chairman, ask that we revert to introduce some guests? Title: Wednesday, February 28, 1996 8:00 p.m. Date: 96/02/28 THE CHAIRMAN: All those in favour of introduction of visitors, please signify by saying aye. head: Committee of Supply [Mr. Tannas in the Chair] HON. MEMBERS: Aye. THE CHAIRMAN: I'd like to call the committee to order. THE CHAIRMAN: Opposed? Carried. head: Main Estimates 1996-97 head: Introduction of Guests Transportation and Utilities DR. WEST: I'd like to take this opportunity to introduce some THE CHAIRMAN: Although lottery funds are under the responsi- very important people as it relates to this budget this year. bility of the Minister of Transportation and Utilities, they are not They've worked very hard on the reorganization and restructuring to be considered this evening because of course under our of both Transportation and Utilities and the Gaming and Liquor Standing Orders they're on a separate occasion. Commission. Somebody said to me on the way in, “I didn't think there were that many people left in the department,” but I want to MR. DAY: Could you repeat the remarks you just made related assure you that the right people are left, and I'd like to introduce to the lottery estimates? them. If they'd stand as I call their name, then they would receive the warm welcome of this House: Jack Davis, the Deputy THE CHAIRMAN: The committee is reminded that we have Minister of Transportation and Utilities; Jim Sawchuk, assistant under consideration the estimates of the Department of Transpor- deputy minister of safety and technical services; June MacGregor, tation and Utilities. -

Industrial Development of Lethbridge: a Geographer's Interpretation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OPUS: Open Uleth Scholarship - University of Lethbridge Research Repository University of Lethbridge Research Repository OPUS http://opus.uleth.ca Faculty Research and Publications MacLachlan, Ian 2004-01 Industrial Development of Lethbridge: A Geographer's Interpretation MacLachlan, Ian http://hdl.handle.net/10133/304 Downloaded from University of Lethbridge Research Repository, OPUS Industrial Development of Lethbridge: A Geographer's Interpretation Ian MacLachlan, Associate Professor of Geography The University of Lethbridge This paper was originally written as a field trip guide for the 1999 Meeting of the Canadian Association of Geographers. This revision is written for the Economic Development Department of the City of Lethbridge. The paper uses mainly secondary sources and field observation to provide the broad geographic and historical background necessary to understand Lethbridge’s contemporary industrial economy. Corrections, questions and suggestions for revision are welcome; the author may be reached at [email protected]. The assistance of Greg Ellis Archivist, Galt Museum and Kel Hansen, City of Lethbridge is gratefully acknowledged. September 1, 2000, minor modifications in January 2004 The Bison Economy The earliest economic activity in the Lethbridge area can be traced back at least 11,500 years, the earliest date of stone artifacts found in Southern Alberta. By 5000 BC hunting and gathering cultures were killing and butchering bison at cliff sites in the foothills such as the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, some 70 kilometers to the west of the present-day Lethbridge. The absence of large concentrations of stone implements at any single location in Southern Alberta suggests a nomadic Aboriginal lifestyle. -

Last Name First Name Organization Province AJAYI TOSIN AB Ashton Jane BC Brar Sundeep BC Christensen Donna AB Dayton Peggy BC De

Last Name First Name Organization Province AJAYI TOSIN AB Ashton Jane BC Brar Sundeep BC Christensen Donna AB Dayton Peggy BC Decka Richard MB Dhillon Harinder BC Egan Christopher ONT Fillion Suzanne BC Gauzshtein Ilnur BC Goughnour Dave AB Harriman Dunni SK Kalen-Sukra Diane BC Koch Diane BC Lalonde Gord ONT Lecy Katherine BC McIntyre Rick ONT Neumann Nancy MB Renaud Wesley BC Saleem Lubna AB Shaker Michael Edgar SIEBEN DAN AB Smeenk Andrea BC Stowe Syd BC TERNENT STEVE BC Wenstrom Evelyn AB Wojtkiw Rick AB Vincenzi Flori 100 Mile House, District of BC Morrison John 1257041 Alberta Limited AB Gladden Duane AAMDC AB MORRISON OLLY AAMDC AB Badyal Tajinder Abbotsford, City of BC Basatia Komal Abbotsford, City of BC Grewal Sandi Abbotsford, City of BC Lewis Emily Abbotsford, City of BC Millard Randy Abbotsford, City of BC Sharma Rajat Abbotsford, City of BC Towns Josh Abbotsford, City of BC Veenbaas Jenny Abbotsford, City of BC Stevenson Sharon AFOA Manitoba mb Chouhan Sukhvinder AFOABC BC Giles Elixabeth Agilyx Solutions BC Webb Patrick Agilyx Solutions bc Van Sleuwen Terri AGLG of BC BC Bigney Meghan Airdrie, City of AB BISWAS PALKI Airdrie, City of AB Labait Monica Airdrie, City of AB MARIC MLADEN Airdrie, City of AB Schindeler Shannon Airdrie, City of AB Fong Teri Alberni-Clayoquot, Regional District of BC McGifford Andrew Alberni-Clayoquot, Regional District of BC Holinski Troy Alberta Capital Finance Authority AB Nosko Travis Alberta Municipal Affairs AB Beadle Justin Alert Bay, Village of BC Sharma Amrit Alert Bay, Village of BC Arora Meeta Algonquin Power & Utilities Corp. -

Disposition 20373-D01-2015

April 24, 2015 Disposition 20373-D01-2015 FortisAlberta Inc. 320 – 17th Avenue S.W. Calgary, Alberta T2S 2V1 Attention: Mr. Miles Stroh Director, Regulatory FortisAlberta Inc. 2015 Municipal Assessment Rider A-1 Proceeding 20373 1. The Alberta Utilities Commission received your application dated April 22, 2015, requesting approval of the 2015 municipal assessment Rider A-1 percentages by taxation authority effective July 1, 2015, which is attached as Appendix 1. The percentages were calculated in accordance with Order U2004-192.1 2. The above-noted application is accepted as a filing for acknowledgement. (original signed by) Neil Jamieson Commission Member Attachment 1 Order U2004-192: FortisAlberta 2004 Municipal Assessment Rider A-1, Application 1341303-1, File 8600- A06, June 18, 2004. Appendix 1 Alberta Utilities Commission Page 1 of 3 April 24, 2015 Disposition 20373-D01-2015 FortisAlberta Inc. 2015 Municipal Assessment Rider A-1 Application 2015 Rate Sheets RIDER A-1 MUNICIPAL ASSESSMENT RIDER Effective: July 1, 2015 Availability The percentages below apply to the base Distribution Tariff charges at each Point of Service, according to the taxation authority in which the Point of Service is located. Rates 21, 23, 24, 26, 29, 38, and 65 are exempt from Rider A-1. Rider A-1 Number Name Rider Number Name Rider 03-0002 Acme, Village Of 2.12% 04-0414 Burnstick Lake, S.V. 0.41% 01-0003 Airdrie, City Of 0.76% 01-0046 Calgary, City Of (0.24%) 03-0004 Alberta Beach, S.V. Of 1.41% 02-0047 Calmar, Town Of 1.15% 25-0466 Alexander First Nation 1.61% 06-0049 Camrose County 0.86% 25-0467 Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation1.08% 01-0048 Camrose, City Of 0.65% 03-0005 Alix, Village Of 0.58% 02-0050 Canmore, Town Of 0.73% 03-0007 Amisk, Village Of 1.64% 06-0053 Cardston County 0.61% 04-0009 Argentia Beach, S.V. -

Fort Mcmurray Books

Fort McMurray Branch, AGS: Library Resources 1 Resource Type Title Author Book "A Very Fine Class of Immigrants" Prince Edward Island's Scottish Pioneers 1770‐ Lucille H. Campey Book "Dit" Name: French‐Canadian Surnames, Aliases, Adulterations and Anglicizati, The Robert J. Quinton Book "Where the Redwillow Grew"; Valleyview and Surrounding Districts Valleyview and District Oldtimers Assoc. Book <New Title> Shannon Combs‐Bennett Book 10 Cemeteries, Stirling, Warner, Milk River & Coutts Area, Index Alberta Genealogical Society Book 10 Cemeteries,Bentley, Blackfalds, Eckville, Lacombe Area Alberta Genealogical Society Book 100 GENEALOGICAL REFERENCE WORKS ON MICROFICHE Johni Cerny & Wendy Elliot Book 100 Years of Nose Creek Valley History Sephen Wilk Book 100 Years The Royal Canadian Regiment 1883‐1983 Bell, Ken and Stacey, C.P. Book 11 Cemeteries Bashaw Ferintosh Ponoka Area, Index to Grave Alberta Genealogical Society Book 11 Cemeteries, Hanna, Morrin Area, Index to Grave Markers & Alberta Genealogical Society Book 12 Cemeteries Rimbey, Bluffton, Ponoka Area, Index to Grave Alberta Genalogical Society Book 126 Stops of Interest in British Columbia David E. McGill Book 16 Cemeteries Brownfield, Castor, Coronation, Halkirk Area, Index Alberta Genealogical Society Book 16 Cemeteries, Altario, Consort, Monitor, Veteran Area, Index to Alberta Genealogical Society Book 16 Cemeteries,Oyen,Acadia Valley, Loverna Area, Index Grave Alberta Genealogical Society Book 1666 Census for Nouvelle France Quintin Publications Book 1762 Census of the Government -

Watershed Stewardship in Alberta: a Directory of Stewardship Groups, Support Agencies, and Resources

WATERSHED STEWARDSHIP IN ALBERTA: A DIRECTORY OF STEWARDSHIP GROUPS, SUPPORT AGENCIES AND RESOURCES APRIL 2005 INTRODUCTION FOREWORD This directory of WATERSHED STEWARDSHIP IN ALBERTA has been designed to begin a process to meet the needs of individuals, stewardship groups, and support agencies (including all levels of government, non- governmental organizations, and industry). From recent workshops, surveys, and consultations, community- based stewards indicated a need to be better connected with other stewards doing similar work and with supporting agencies. They need better access to information, technical assistance, funding sources, and training in recruiting and keeping volunteers. Some groups said they felt isolated and did not have a clear sense that the work they were doing was important and appreciated by society. A number of steps have occurred recently that are beginning to address some of these concerns. The Alberta Stewardship Network, for example, has been established to better connect stewards to each other and to support agencies. Collaboration with other provincial and national networks (e.g. Canada’s Stewardship Communities Network) is occurring on an on-going basis. Internet-based information sites, such as the Stewardship Canada Portal (www.stewardshipcanada.ca), are being established to provide sources of information, linkages to key organizations, and newsletters featuring success stories and progress being made by grassroots stewards. These sites are being connected provincially and nationally to keep people informed with activities across Canada. The focus of this directory is on watershed stewardship groups working in Alberta. The term ‘watershed’ is inclusive of all stewardship activities occurring on the landscape, be they water, air, land, or biodiversity-based. -

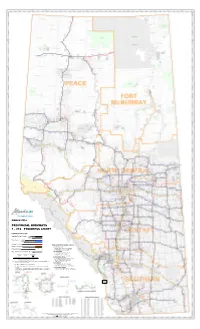

Provincial Highways 1 - 216 Progress Chart

Transportation MARCH 2016 PROVINCIAL HIGHWAYS 1 - 216 PROGRESS CHART Highway Surface Type Asphaltic Surface Course - Final - Staged Base Course - ASBC - DSC F Graded / Gravelled o re s t TRANSPORTATION REGION OFFICES ry T ru n Interchange k R Multi-lane / Divided o a SOUTHERN REGION d 300 Exit Number SOUTHERN REGION HEAD OFFICE - LETHBRIDGE Proposed Route LETHBRIDGE DISTRICT OFFICE - LETHBRIDGE CALGARY DISTRICT OFFICE - CALGARY 500 - 986 Provincial Highway Series CENTRAL REGION CENTRAL REGION HEAD OFFICE - RED DEER RED DEER DISTRICT OFFICE - RED DEER Trans-Canada 1 - 216 Provincial 500 - 986 Provincial Highways Highways Highways HANNA DISTRICT OFFICE - HANNA VERMILION DISTRICT OFFICE - VERMILION 500 NORTH CENTRAL REGION 0 20406080100 NORTH CENTRAL REGION HEAD OFFICE - BARRHEAD Kilometers STONY PLAIN DISTRICT OFFICE - STONY PLAIN North American Datium 1983, 10° Transverse Mercator ATHABASCA DISTRICT OFFICE - ATHABASCA Note: 1. 500 - 986 Provincial Highways are shown for location. Refer to Provincial Highways 500 - 986 EDSON DISTRICT OFFICE - EDSON Progress Chart for detailed information PEACE REGION 2. The control section distances are shown in kilometres. PEACE REGION HEAD OFFICE - PEACE RIVER PEACE RIVER DISTRICT OFFICE - PEACE RIVER 3. The control section distances have been derived from GPS collection of assumed highway GRANDE PRAIRIE DISTRICT OFFICE - GRANDE PRAIRIE center line. FORT McMURRAY REGION 4. Information presented on this map originates from various sources and is intended for general FORT McMURRAY REGION HEAD OFFICE - EDMONTON use only. Please be advised that some information may have been added, amended and or FORT McMURRAY REGION FIELD OFFICE - FORT McMURRAY deleted since its creation. Forestry Trunk Road Between Highway 532 and Highway 541 is under Alberta Transportation Authority. -

2016 Community Report

2016 Community Report educationmatters JOINT MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD CHAIR AND EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR BOARD OF GOVERNORS Mike Shaikh, Chair Education is the fundamental ingredient for a successful society. Nancy Close, Vice Chair Mark E. Saar, Treasurer Education improves the quality of life and With every program and every student that David McKinnon, Secretary you are contributing to a better life for you support, there is a common theme. Every Liana Appelt thousands of publicly educated children by student matters. That is why we are called Dr. Aleem Bharwani supporting educational enhancements and EducationMatters. Joy Bowen-Eyre student awards through EducationMatters. Dr. Gene Edworthy On behalf of the Board of Governors, and our Lynn Ferguson Your gifts are revolutionizing classrooms, staff, we commit to you that we will continue Gregory Francis Rod Garossino and making way for learners with varied to work hard to provide important enhance- Dr. Judy Hehr challenges, so that they may fully participate ments for Calgary Board of Education’s K-12 Hanif Ladha in their educational opportunities. students, and continue to work quickly and Enza Rosi efficiently with you, our valued donors. Dr. Richard Sigurdson You are providing food for Fuel for School Dr. Charles Webber programs, and helping teenagers stay in Please continue to support students in school through alternative choice programs. Calgary, and thank you for investing in HONOURARY AMBASSADORS You are helping our most vulnerable futures. Join us on Facebook, Twitter and on Joanne Cuthbertson children. our website to hear more about the possibil- David Pickersgill ities you are helping to create for Calgary’s This report celebrates what we have made students. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 351 634 CG 024 635 TITLE Stay In--You Win: Module Four. Dropout Prevention Programs That Work. INSTITUTION Mediaworks Ltd. SPONS AGENCY Alberts Dept. of 2ducation, Edmonton. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7732-0748-1 PUB DATE Jan ("2 NOTE 131p.; For related documents, see CG 024 632-634. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Dropout Prevention; *Dropout Programs; Foreign Countries; High SchoolF; *High School'Students; Potential Dropouts IDENTIFIERS Alberta; *Stay In You Win Project AB ABSTRACT Module Four of the Alberta project "Stay In--You Win" is presented in this document. This module is designed to generate ideas for planning effective initiatives for schools. The stated objectives of this module are to provide a listing of dropout prevention programs in Alberta high schools; to encourage interpersonal networking among educators concerned with stay in school initiatives; to outline a variety of dropout prevention programs which can generate ideas for a school's Stay In--You Win initiatives; and to provide guidelines for the design of effective dropout prevention programs. Guidelines for effective education and remediation programs for youth are then presented. Eighteen dropout prevention projects in Alberta high schools are described. Sixty-nine dropout program project descriptions selected from the research literature are also presented. These are grouped into the categories of general programs; technology programs; programs specifically for girls; and business partnerships. Synopses for each of the four categories are included. Planning charts for the Stay In--You Win program are included.(ABL) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Educationmatters 2017 Report to Community “Where Was This When I Needed It in Grade One?”

educationmatters 2017 Report to Community “Where was this when I needed it in grade one?” Grade three student at William Reid School while learning to use math manipulatives to better understand subtraction Board of Governors Message from Board Chair & Executive Director Mike Shaikh, Chair Nancy Close, Vice Chair Mark E. Saar, Treasurer David McKinnon, Secretary Dr. Liana Appelt Steve Aubin Dr. Aleem Bharwani Joy Bowen-Eyre Martin Cej Lisa Davis Dr. Gene Edworthy Lynn Ferguson Amanda Field Maslow’s famous “Hierarchy of Needs” into classrooms, providing tools to assist Gregory Francis lays out a basic set of conditions for each with written and mathematical literacy, Richard Hehr of us to live happy, healthy, and fulfilled and creating opportunities to build Hanif Ladha lives. At EducationMatters, we work with career and life skills, you are ensuring Dr. Richard Sigurdson the community in Calgary to meet our that students across our city are getting Dr. Charles Webber students’ needs and empower them with the most from their education. enriched educational opportunities. Honourary Ambassadors In fifteen years, we have come to realize Your gifts support students’ physical that education works best when students Joanne Cuthbertson needs by providing nutritious meals to are excited to learn, are able to experi- David Pickersgill those who would otherwise arrive to ence success, and can plan for a future Contact Us class hungry. Community partners, like of their own design. Your investment WP Puppet Theatre’s “View from the is delivering important returns in the 403-817-7468 Inside” program, support psychological community by allowing students in each [email protected] needs by encouraging discussions quadrant of our city to build a future and 1221 8 Street SW about mental wellness.