P:\00000 USSC\VA State Board of Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAREERS DONALD SHUM ’13 Is an Associate at Cooley in New York City; ALYSSA KUHN ’13 Is Clerking for Judge Joseph F

CAREERS DONALD SHUM ’13 is an associate at Cooley in New York City; ALYSSA KUHN ’13 is clerking for Judge Joseph F. Bianco of the Eastern District of New York after working as an associate at Gibson Dunn in New York; and ZACH TORRES-FOWLER ’12 is an associate at Pepper Hamilton in Philadelphia. THE CAREER SERVICES PROGRAM AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA SCHOOL OF LAW is one of the most successful among national law VIRGINIA ENJOYS A REPUTATION FOR PRODUCING LAWYERS who master the schools and provides students with a wide range of job intellectual challenges of legal practice, and also contribute broadly to the institutions they join through strong leadership and interpersonal skills. opportunities across the nation and abroad. AS A RESULT, PRIVATE- AND PUBLIC-SECTOR EMPLOYERS HEAVILY RECRUIT VIRGINIA STUDENTS EACH YEAR. Graduates start their careers across the country with large and small law firms, government agencies and public interest groups. ZACHARY REPRESENTATIVE RAY ’16 EMPLOYERS TAYLOR clerked for U.S. CLASSES OF 2015-17 STEFFAN ’15 District Judge clerked for Gershwin A. Judge Patrick Drain of the LOS ANGELES Higginbotham of Eastern District UNITED Hewlett Packard Enterprise Jones Day the 5th U.S. Circuit of Michigan STATES Dentons Jones Day Morgan, Lewis & Bockius Court of Appeals SARAH after law school, Howarth & Smith Reed Smith Morrison & Foerster in Austin, Texas, PELHAM ’16 followed by a ALABAMA Latham & Watkins Simpson Thacher & Bartlett Orrick, Herrington & before returning is an associate clerkship with BIRMINGHAM Mercer Consulting Sullivan & Cromwell Sutcliffe to Washington, with Simpson Judge Roger L. REDWOOD CITY D.C., to work for Thacher & Gregory of the Bradley Arant Boult Morgan, Lewis & Bockius Perkins Coie Covington Bartlett in New 4th U.S. -

Establishment of Charter Schools in the Commonwealth of Virginia Grace E

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs Publications Public Affairs 2016 Establishment of Charter Schools in the Commonwealth of Virginia Grace E. Harris Leadership Institute, Virginia Commonwealth University Shermese Epps Germika Pegram See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/wilder_pubs Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, Law Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/wilder_pubs/39 This Research Report is brought to you for free and open access by the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Grace E. Harris Leadership Institute, Virginia Commonwealth University; Shermese Epps; Germika Pegram; Edward Reed; Brenda Sampe; and Courtney Warren This research report is available at VCU Scholars Compass: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/wilder_pubs/39 ESTABLISHMENT OF CHARTER SCHOOLS IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA TEAM MEMBERS Shermese Epps, Chiles Law Offices, P.C. Germika Pegram, Private Mental Health Provider Edward Reed, Senate of Virginia, Senator Rosalyn R. Dance Brenda Sampe, Chesterfield Colonial Heights -

2020 Virginia Capitol Connections

Virginia Capitol Connections 2020 ai157531556721_2020 Lobbyist Directory Ad 12022019 V3.pdf 1 12/2/2019 2:39:32 PM The HamptonLiveUniver Yoursity Life.Proto n Therapy Institute Let UsEasing FightHuman YourMisery Cancer.and Saving Lives You’ve heard the phrases before: as comfortable as possible; • Treatment delivery takes about two minutes or less, with as normal as possible; as effective as possible. At Hampton each appointment being 20 to 30 minutes per day for one to University Proton The“OFrapy In ALLstitute THE(HUPTI), FORMSwe don’t wa OFnt INEQUALITY,nine weeks. you to live a good life considering you have cancer; we want you INJUSTICE IN HEALTH IS THEThe me MOSTn and wome n whose lives were saved by this lifesaving to live a good life, period, and be free of what others define as technology are as passionate about the treatment as those who possible. SHOCKING AND THE MOSTwo INHUMANrk at the facility ea ch and every day. Cancer is killing people at an alBECAUSEarming rate all acr osITs ouOFTENr country. RESULTSDr. William R. Harvey, a true humanitarian, led the efforts of It is now the leading cause of death in 22 states, behind heart HUPTI becoming the world’s largest, free-standing proton disease. Those states are Alaska, ArizoINna ,PHYSICALCalifornia, Colorado DEATH.”, therapy institute which has been treating patients since August Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, 2010. Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, NewREVERENDHampshir DR.e, Ne MARTINw Me LUTHERxico, KING, JR. North Carolina, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West “A s a patient treatment facility as well as a research and education Virginia, and Wisconsin. -

Virginia-Voting-Record.Pdf

2017 | Virginia YOUR LEGISLATORS’ VOTING RECORD ON VOTING RECORD SMALL BUSINESS ISSUES: 2017 EDITION Issues from the 2016 and 2017 General Assembly Sessions: Floor votes by your state legislators on key small business issues during the past two sessions of the Virginia General Assembly are listed inside. Although this Voting Record does not reflect all elements considered by a lawmaker when voting or represent a complete profile of a legislator, it can be a guide in evaluating your legislator’s attitude toward small business. Note that many issues that affect small business are addressed in committees and never make it to a floor vote in the House or Senate. Please thank those legislators who supported small business and continue to work with those whose scores have fallen short. 2016 Legislation 5. Status of Employees of Franchisees (HB 18) – Clarifies in Virginia law that a franchisee or any 1. Direct Primary Care (HB 685 & SB 627) – employee of the franchisee is not an employee of the Clarifies that direct primary care (DPC) agreements franchisor (parent company). A “Yes” vote supports are not insurance policies but medical services and the NFIB position. Passed Senate 27-12; passed provides a framework for patient and consumer pro- House 65-34. Vetoed by governor. tections. These clarifications are for employers who want to offer DPC agreements combined with health 6. Virginia Growth and Opportunity Board insurance as a choice for patients to access afford- and Fund (HB 834 & SB 449) – Establishes the able primary care. A “Yes” vote supports the NFIB Virginia Growth and Opportunity Board to administer position. -

How to Draw Redistricting Plans That Will Stand up in Court

How to Draw Redistricting Plans That Will Stand Up in Court Peter S. Wattson National Conference of State Legislatures Online Redistricting Seminar DENVER, COLORADO JANUARY 7, 2021 Peter S. Wattson is beginning his sixth decade of redistricting. He served as Senate Counsel to the Minnesota Senate from 1971 to 2011 and as General Counsel to Governor Mark Dayton from January to June 2011. He assisted with drawing, attacking, and defending redistricting plans throughout that time. He served as Staff Chair of the National Conference of State Legislatures’ Reapportionment Task Force in 1989, its Redistricting Task Force in 1999, and its Committee on Redistricting and Elections in 2009. Since retiring in 2011, he has participated in redistricting lawsuits in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Florida, and lectured regularly at NCSL seminars on redistricting. Contents I. Introduction. 1 A. Reapportionment and Redistricting . 1 B. Why Redistrict? . 1 1. Reapportionment of Congressional Seats. 1 2. Population Shifts within a State . 2 C. The Facts of Life . 3 1. Equal Population. 3 2. Gerrymandering . 4 a. Packing. 4 b. Cracking. 4 c. Pairing . 4 d. Kidnapping . 5 e. Creating a Gerrymander . 6 D. The Need for Limits . 7 1. Who Draws the Plans . 7 2. Data that May be Used . 7 3. Review by Others . 7 4. Districts that Result . 8 II. Draw Districts of Equal Population . 8 A. Use Official Census Bureau Population Counts. 8 1. Alternative Population Counts . 8 2. Use of Sampling to Eliminate Undercount . 9 3. Exclusion of Undocumented Aliens. 10 4. Inclusion of Overseas Military Personnel. 10 B. Census Geography . 10 1. -

Ninety Percent of VEA Fund-Backed Candidates Win June 11 Primaries

116 South Third Street ∙ Richmond, VA 23219 www.veanea.org ∙ 800-552-9554 (Toll Free) ∙ 804-775-8379 (Fax) For Immediate Release – June 12, 2019 Contact: John O’Neil, VEA Communications, 804-775-8316, [email protected] Ninety percent of VEA Fund-backed candidates win June 11 primaries Nine of 10 candidates recommended by the Virginia Education Association Fund for Children and Public Education who participated in primaries yesterday won their races, says Jim Livingston, chair of the VEA Fund. “The VEA Fund rigorously evaluates candidates for public office to make sure they support students in our public schools and those who work with them,” said Livingston, who is president of the 40,000- member VEA. “Our strong showing in yesterday’s primary elections is testimony to the quality of our process and to the candidates who prevailed. We believe it also shows the public cares deeply about education and will support candidates with the ideas and commitment to move us forward. Congratulations to these nine supporters of our students.” VEA Fund-backed candidates who won yesterday were: Senate: Lynwood Lewis (6th); Cheryl Turpin (7th); Barbara Favola (31st); Jennifer Boysko (33rd); and Dick Saslaw (35th). House of Delegates: Israel O’Quinn (5th); Kaye Kory (38th); Alfonso Lopez (49th); and Luke Torian (52nd). Rosalyn Dance (Senate, 16th), recommended by the VEA Fund, was upset in her primary. Livingston said of Dance, “Senator Dance has been consistent in her strong support of our public schools, and in this last legislative session she helped to win the biggest increase in state funding for much-needed school counselors in 30 years. -

Virginia Interfaith Center 2021 Legislative Priorities

Virginia Interfaith Center 2021 Legislative Priorities Criminal Justice Reform Abolish the Death Penalty in Virginia- SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR! o SB 1165- Senator Scott Surovell/ HB 2263- Delegate Mike Mullin o Becomes law on July 1, 2021 Economic Justice Paid Sick Days – Establish a standard of 5 paid sick days for full-time employees for essential workers- AMENDED VERSION PASSED THAT WILL GET 30,000 HOME CARE WORKERS PAID SICK DAYS! SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR! o HB 2137- Delegate Elizabeth Guzman o Becomes law on July 1, 2021 Environmental Justice Water is a Human Right– support a proclamation outlining importance of clean, safe, affordable drinking water as a right for all residents of the Commonwealth- RESOLUTION PASSED! o HJ 538- Delegate Lashrecse Aird Equitably Modernize Public Transit- support a study on public transit overhaul- RESOLUTION PASSED! o HJ 542- Delegate Delores McQuinn Environmental Justice Act- support improvements to ground breaking legislation passed in 2020- DID NOT PASS o SB 1318- Senator Ghazala Hashmi/ HB 2074- Delegate Shelly Simonds Farm Worker Justice Access to the Minimum Wage- many farmworkers in Virginia are not subject to federal or state minimum wage laws leading to some to be paid under $5/hour- DID NOT PASS o HB 1786- Delegate Jeion Ward Heat Stress- Create standards for outdoor workers including water breaks and shade access on extremely hot days- NON-LEGISLATIVE SOLUTION AGREED TO o SB 1358- Senator Ghazala Hashmi/ HB 1785- Delegate Jeion Ward Health Equity Prenatal Care for All Mothers – Support a budget amendment to extend Medicaid/FAMIS MOMS prenatal care to undocumented women who meet all other non-immigration eligibility criteria- BUDGET AMENDMENT PASSED, INCLUDED IN THE FINAL BUDGET! o Budget Amendment: HB 1800 Item 312 #1h & 313 #16h - Delegate Elizabeth Guzman o Budget Amendment: SB 1100 Item # TBD- Senator Jennifer McClellan . -

The Polarization Crisis in Congress: the Decline of Crossover Representatives and Crossover Voting in the U.S

Jul November 2013 THE POLARIZATION CRISIS IN CONGRESS: THE DECLINE OF CROSSOVER REPRESENTATIVES AND CROSSOVER VOTING IN THE U.S. HOUSE Spotlighted Facts: Fewer Crossover Representatives*: o Number of Crossover Representatives in 1993: 113 . 88 Democrats in Republican districts . 25 Republicans in Democratic districts o Number of Crossover Representatives in 2013: 26 . 16 Democrats in Republican districts . 10 Republicans in Democratic districts *Crossover Representative – a member whose district favors the opposite party Less Moderation: o Percentage of Moderates* in the House in 1993: 24% o Percentage of Moderates in the House in 2011: 4% *Moderate defined as between 0.25 and -0.25 NOMINATE score Increased Polarization: o Distance between Republicans’ and Democrats’ NOMINATE* score in 1993: 0.74 o Distance between Republicans’ and Democrats’ NOMINATE score in 2011: 1.069 * NOMINATE score – ideological ranking where -1 is the most liberal and +1 is the most conservative Crossover Effects: o Crossover Republican’s average NOMINATE score in 2011*: 0.490, compared to 0.675 for the average Republican score o Crossover Democrat’s average NOMINATE score in 2011: -0.217, compared to -0.394 for the average Democrat score *NOMINATE scores are only available for members who were elected prior to 2012 1 If you are the whip in either party you are liking this [polarization] – it makes your job easier. In terms of getting things done for the country, that’s not the case. - former Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott (National Journal, February 24, 2011) It will not surprise many political observers that “crossover voting” – that is, when members of Congress vote against a majority of their party – has become less prevalent in Washington in recent years. -

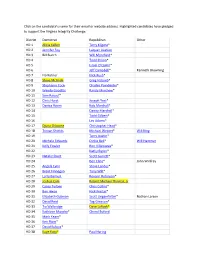

Click on the Candidate's Name for Their Email Or Website Address

Click on the candidate’s name for their email or website address. Highlighted candidates have pledged to support the Virginia Integrity Challenge. District Democrat Republican Other HD 1 Alicia Kallen Terry Kilgore* HD 2 Jennifer Foy Laquan Austion HD 3 Bill Bunch Will Morefield* HD 4 Todd Pillion* HD 5 Israel O'Quinn* HD 6 Jeff Campbell* Kenneth Browning HD 7 Flo Ketner Nick Rush* HD 8 Steve McBride Greg Habeeb* HD 9 Stephanie Cook Charles Poindexter* HD 10 Wendy Gooditis Randy Minchew* HD 11 Sam Rasoul* HD 12 Chris Hurst Joseph Yost* HD 13 Danica Roem Bob Marshall* HD 14 Danny Marshall* HD 15 Todd Gilbert* HD 16 Les Adams* HD 17 Djuna Osborne Christopher Head* HD 18 Tristan Shields Michael Webert* Will King HD 19 Terry Austin* HD 20 Michele Edwards Dickie Bell* Will Hammer HD 21 Kelly Fowler Ron Villanueva* HD 22 Kathy Byron* HD 23 Natalie Short Scott Garrett* HD 24 Ben Cline* John Winfrey HD 25 Angela Lynn Steve Landes* HD 26 Brent Finnegan Tony Wilt* HD 27 Larry Barnett Roxann Robinson* HD 28 Joshua Cole Robert Michael Thomas, Jr HD 29 Casey Turben Chris Collins* HD 30 Ben Hixon Nick Freitas* HD 31 Elizabeth Guzman Scott Lingamfelter* Nathan Larson HD 32 David Reid Tag Greason* HD 33 Tia Walbridge Dave LaRock* HD 34 Kathleen Murphy* Cheryl Buford HD 35 Mark Keam* HD 36 Ken Plum* HD 37 David Bulova* HD 38 Kaye Kory* Paul Haring HD 39 Vivian Watts* HD 40 Donte Tanner Tim Hugo* HD 41 Eileen Filler-Corn* HD 42 Kathy Tran Lolita Mancheno-Smoak HD 43 Mark Sickles* HD 44 Paul Krizek* HD 45 Mark Levine* HD 46 Charniele Herring* HD 47 Patrick -

Vietnamese Glossary of Election Terms.Pdf

U.S. ELECTION AssISTANCE COMMIssION ỦY BAN TRợ GIÚP TUYểN Cử HOA Kỳ 2008 GLOSSARY OF KEY ELECTION TERMINOLOGY Vietnamese BảN CHÚ GIảI CÁC THUậT Ngữ CHÍNH Về TUYểN Cử Tiếng Việt U.S. ELECTION AssISTANCE COMMIssION ỦY BAN TRợ GIÚP TUYểN Cử HOA Kỳ 2008 GLOSSARY OF KEY ELECTION TERMINOLOGY Vietnamese Bản CHÚ GIải CÁC THUậT Ngữ CHÍNH về Tuyển Cử Tiếng Việt Published 2008 U.S. Election Assistance Commission 1225 New York Avenue, NW Suite 1100 Washington, DC 20005 Glossary of key election terminology / Bản CHÚ GIải CÁC THUậT Ngữ CHÍNH về TUyển Cử Contents Background.............................................................1 Process.................................................................2 How to use this glossary ..................................................3 Pronunciation Guide for Key Terms ........................................3 Comments..............................................................4 About EAC .............................................................4 English to Vietnamese ....................................................9 Vietnamese to English ...................................................82 Contents Bối Cảnh ...............................................................5 Quá Trình ..............................................................6 Cách Dùng Cẩm Nang Giải Thuật Ngữ Này...................................7 Các Lời Bình Luận .......................................................7 Về Eac .................................................................7 Tiếng Anh – Tiếng Việt ...................................................9 -

2011 Political Contributions

2011 POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS 2011 Lilly Political Contributions 2 Government actions such as price controls, pharmaceutical manufacturer rebates, the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), and access to Lilly medicines affect our ability to invest in innovation. Lilly has a comprehensive government relations operation to have a voice in the public policymaking process at both the state and federal levels. Lilly is committed to participating in the political process as a responsible corporate citizen to help inform the U.S. debate over health care and pharmaceutical innovation. As a company that operates in a highly competitive and regulated industry, Lilly must participate in the political process to fulfill its fiduciary responsibility to its shareholders, and its overall responsibilities to its customers and its employees. Corporate Political Contribution Elected officials, no matter what level, have an impact on public policy issues affecting Lilly. We are committed to backing candidates who support public policies that contribute to pharmaceutical innovation and healthy patients. A number of factors are considered when reviewing candidates for support. The following evaluation criteria are used to allocate political contributions: • Has the candidate historically voted or announced positions on issues of importance to Lilly, such as pharmaceutical innovation and health care? • Has the candidate demonstrated leadership on key committees of importance to our business? • Does the candidate demonstrate potential for legislative leadership? -

Members by Circuit (As of January 3, 2017)

Federal Judges Association - Members by Circuit (as of January 3, 2017) 1st Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit Bruce M. Selya Jeffrey R. Howard Kermit Victor Lipez Ojetta Rogeriee Thompson Sandra L. Lynch United States District Court District of Maine D. Brock Hornby George Z. Singal John A. Woodcock, Jr. Jon David LeVy Nancy Torresen United States District Court District of Massachusetts Allison Dale Burroughs Denise Jefferson Casper Douglas P. Woodlock F. Dennis Saylor George A. O'Toole, Jr. Indira Talwani Leo T. Sorokin Mark G. Mastroianni Mark L. Wolf Michael A. Ponsor Patti B. Saris Richard G. Stearns Timothy S. Hillman William G. Young United States District Court District of New Hampshire Joseph A. DiClerico, Jr. Joseph N. LaPlante Landya B. McCafferty Paul J. Barbadoro SteVen J. McAuliffe United States District Court District of Puerto Rico Daniel R. Dominguez Francisco Augusto Besosa Gustavo A. Gelpi, Jr. Jay A. Garcia-Gregory Juan M. Perez-Gimenez Pedro A. Delgado Hernandez United States District Court District of Rhode Island Ernest C. Torres John J. McConnell, Jr. Mary M. Lisi William E. Smith 2nd Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Barrington D. Parker, Jr. Christopher F. Droney Dennis Jacobs Denny Chin Gerard E. Lynch Guido Calabresi John Walker, Jr. Jon O. Newman Jose A. Cabranes Peter W. Hall Pierre N. LeVal Raymond J. Lohier, Jr. Reena Raggi Robert A. Katzmann Robert D. Sack United States District Court District of Connecticut Alan H. NeVas, Sr. Alfred V. Covello Alvin W. Thompson Dominic J. Squatrito Ellen B.