SIGNATURE PAGE for RESEARCH NATURAL AREA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology and Paleontology of the Southwest Quarter of the Big Bend Quadrangle Shasta County, California

GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY OF THE SOUTHWEST QUARTER OF THE BIG BEND QUADRANGLE SHASTA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA By ALBERT F. SANBORN Geologist, Standard Oil Company of California Salt Lake City, Utah Special Report 63 CALIFORNIA DIVISION OF MINES FERRY BUILDING, SAN FRANCISCO, 1960 STATE OF CALIFORNIA EDMUND G. BROWN, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES eWITT NELSON, Director DIVISION OF MINES IAN CAMPBELL, Chief Special Report 63 Price 75$ , GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY OF THE SOUTHWEST QUARTER OF THE BIG BEND QUADRANGLE SHASTA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA By Albert F. Sandorn * OUTLINE OF REPORT ABSTRACT Abstract 3 The area covered by this report is the southwest quarter of the Big Bend quadrangle in the vicinity of lntroductu.il 3 the town of Big Bendj Shasta County) California. General stratigraphy 5 This region, which has been geologically unknown, contains sedimentary volcanic strata of Triassic system _ 5 and Mesozoic an( Pit formation (Middle and Upper Triassic) 5 * Cenozoic ages. Hosselkus limestone (Upper Triassic) 7 The Mesozoic deposits are composed of pyroclastic Brock shale (Upper Triassic) 7 rocks, lava flows, tuffaceous sandstone, argillite, and Modin formation (Upper Triassic) 8 limestone. The Mesozoic formations, from the oldest Hawkins Creek member T0 the youngest, are the Pit formation of Middle and I Devils Canyon member 10 jate Triassic age ; the Hosselkus limestone, the Brock Kosk member ll shale, and the Modin formation of Late Triassic age; . the Arvison formation of Early Jurassic age ; and the s sy em -—- -- - --- Bagley andesite and Potem formation of Early and Arvison formation (Lower Jurassic) 11 „•,,, T . ,-.., ., e ,. , ' „ , . .. .. __ . , T 1( Middle Jurassic age. Or the seven formations mapped,rr Nature of the contact of the Triassic and Jurassic svstems 14 ,. -

Taylorsville Region, California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR 353 GEOLOGY OF THE TAYLORSVILLE REGION, CALIFORNIA BY J. S. DILLER WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1908 t f CONTENTS. Page Introduction.............................................................. 7 Location and extent................................................... 7 Outline of geography and geology of region.............................. 7 Topography............................................................... 9 Relief. ............................................................... 9 Diamond Mountain block.......................................... 9 The escarpment. .............................................. 10 The plateau slope.............................................. 10 Valleys on southwest border.................................... 10 Genesee Valley............................................. 10 Indian Valley............................................. 10 Mountain Meadows........................................ 11 Jura Valley................................................ 11 Grizzly Mountain block........................................... 11 Crest line and escarpment..................................... 11 Southwest slope............................................... .12 Drainage.............................................................. 12 Descriptive geology........................................................ 13 General statement........'............................................... 13 Sedimentary rocks.................................................... -

Geology and Ore Deposits of East Shasta Copper-Zinc District Shasta County, California

Geology and Ore Deposits of East Shasta Copper-Zinc District Shasta County, California GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 338 Prepared in cooperation 'with the State of California^ Department of Natural Resources , Division of Mines Geology and Ore Deposits of East Shasta Copper-Zinc District Shasta County, California By JOHN P. ALBERS and JACQUES F. ROBERTSON GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 338 Prepared in cooperation with the State of California^ Department of Natural Resources^ Division of Mines UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1961 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library catalog card for this publication appears after page 107. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.._________________________________________ 1 General geology and geologic history Continued Introduction.______________________________________ 4 Sedimentary and volcanic rocks Continued Location and accessibility________________________ 4 Bully Hill rhyolite. _____ __ - 30 Topography _ _________________________________ 4 Porphyritic quartz keratophyre ___ 31 Climate and vegetation__________________________ 4 Nonporphy ritic quartz keratophyre ___ 31 Previous work in district_______________________ 6 Fragmental quartz keratophyre __ 32 Purpose of this report and methods of investigation. _ 6 Columnar structure_____________---- 33 Fieldwork and acknowledgments________________ 6 Vermicular intergrowths of quartz and General geology and geologic history__________________ 7 34 Sedimentary and volcanic deposits._______________ 10 Pit formation. _____ _______ _______ 35 Copley greenstone._________________________ 10 Shale, mudstone, and siltstone ________ 36 Nonf ragmental mafic lava _______________ 11 Pyroclastic rocks____________-_-----_-_- 36 Block lava_____________________________ 11 Lava flows______---_____-_ ___________ 37 Pyroclastic rocks _______________________ 11 Limestone. -

Pre-Tertiary Stratigraphy and Upper Triassic Paleontology of the Union District Shoshone Mountains Nevada

Pre-Tertiary Stratigraphy and Upper Triassic Paleontology of the Union District Shoshone Mountains Nevada GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 322 Pre-Tertiary Stratigraphy and Upper Triassic Paleontology of the Union District Shoshone Mountains Nevada By N. J. SILBERLING GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 322 A study of upper Paleozoic and lower Mesozoic marine sedimentary and volcanic rocks, with descriptions of Upper Triassic cephalopods and pelecypods UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1959 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ ________________________________________ 1 Paleontology Continued Introduction _______________________________________ 1 Systematic descriptions-------------------------- 38 Class Cephalopoda___--_----_---_-_-_-_-_--_ 38 Location and description of the area ______________ 2 Order Ammonoidea__-__-_______________ 38 Previous work__________________________________ 2 Genus Klamathites Smith, 1927_ __ 38 Fieldwork and acknowledgments________________ 4 Genus Mojsisovicsites Gemmellaro, 1904 _ 39 Stratigraphy _______________________________________ 4 Genus Tropites Mojsisovics, 1875_____ 42 Genus Tropiceltites Mojsisovics, 1893_ 51 Cambrian (?) dolomite and quartzite units__ ______ 4 Genus Guembelites Mojsisovics, 1896__ 52 Pablo formation (Permian?)____________________ 6 Genus Discophyllites Hyatt, -

THE Geologlcal SURVEY of INDIA Melvioirs

MEMOIRS OF THE GEOLOGlCAL SURVEY OF INDIA MElVIOIRS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA VOLUME XXXVI, PART 3 THE TRIAS OF THE HIMALAYAS. By C. DIENER, PH.0., Professor of Palceontology at the Universz'ty of Vienna Published by order of the Government of India __ ______ _ ____ __ ___ r§'~-CIL04l.~y_, ~ ,.. __ ..::-;:;_·.•,· ' .' ,~P-- - _. - •1~ r_. 1..1-l -. --~ ·~-'. .. ~--- .,,- .'~._. - CALCU'l"l'A: V:/f/ .. -:-~,_'."'' SOLD AT THE Ol<'FICE OF THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY o'U-1kI>i'A,- 27, CHOWRINGHim ROAD LONDON: MESSRS. KEGAN PAUT,, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO. BERLIN : MESSRS. FRIEDLANDEH UND SOHN 1912. CONTENTS. am I• PA.GE, 1.-INTBODUCTION l 11.-LJ'rERA.TURE • • 3· III.-GENERAL DE\'ELOPMEKT OF THE Hrn:ALAYA.K TRIAS 111 A. Himalayan Facies 15 1.-The Lower Trias 15 (a) Spiti . Ip (b) Painkhanda . ·20 (c) Eastern Johar 25 (d) Byans . 26 (e) Kashmir 27 (/) Interregional Correlation of fossiliferous horizons 30 (g) Correlation with the Ceratite beds of the Salt Range 33 (Ti) Correlation with the Lower Trias of Europe, Xorth America and Siberia . 36 (i) The Permo-Triassic boundary . 42 II.-The l\Iiddle Trias. (Muschelkalk and Ladinic stage) 55 (a) The Muschelkalk of Spiti and Painkhanda v5 (b) The Muschelkalk of Kashmir . 67 (c) The llluschelka)k of Eastern Johar 68 (d) The l\Iuschelkalk of Byans 68 (e) The Ladinic stage.of Spiti 71 (f) The Ladinic stage of Painkhanda, Johar and Byans 75 (g) Correl;i.tion "ith the Middle Triassic deposits of Europe and America . 77 III.-The Upper Trias (Carnie, Korie, and Rhretic stages) 85 (a) Classification of the Upper Trias in Spiti and Painkhanda 85 (b) The Carnie stage in Spiti and Painkhanda 86 (c) The Korie and Rhretic stages in Spiti and Painkhanda 94 (d) Interregional correlation and homotaxis of the Upper Triassic deposits of Spiti and Painkhanda with those of Europe and America 108 (e) The Upper Trias of Kashmir and the Pamir 114 A.-Kashmir . -

Sheet 2 0F 2

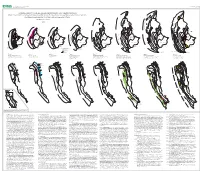

U. S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OPEN-FILE REPORT 02-490 U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SHEET 2 0F 2 CORRELATION OF THE KLAMATH MOUNTAINS AND SIERRA NEVADA Z 156 Sheet 2: Successive accretionary episodes of the Klamath Mountains and northern part of Sierra Nevada, Bc Galice Fm Bc Bc showing related plutonic, volcanic, and metamorphic events Z~160 Z139 Z155 Z 148 By William P. Irwin -160 Z 154 W e P s r o t e t r o 2003 Z~160 n W K e l H 148 a s m Z 174 t e Z~161 a r n t h K t Z 162 e l a r r m a a n t e h Bc t T H 165 e Z162 r Z 149 r a Z 153 Z 142-145 n e f j f j YREKA YREKA f j f j YREKA YREKA YREKA YREKA YREKA YREKA ( P Z 146 e r m F P ( o M r i F F F a o F r e o o F o h 138 n t t o o t r Z 150 r r o a P r t H 167 t ane ane t J t o r t m ane E ane r ane o t ane J o J E J a o o J ane n Z 162 Z~567 t o o J o s a Yreka Yreka r o n Yreka e p n t o r Yreka n e e Yreka n s l Yreka h N Yreka e y n Yreka e r s e P subterr o ( subterr n s P o subterr subterrane e subterr s D subterr J subterr t s Z 415 s r r e t r u s e o e e t o H subterr Z 193-208 t h r r t Z~160 N d e P t v r t t a r e a o e o r t a o N r o a s r e T r N Z~159 F y Z 174 r N r o N n n r s r -164 a n r o r r f W o a P i t R o o t a r i o i e a e n o o r a c h r a n r r r r t n P s k e a e r n Z 404 k o t h H 418 t n e o w h s t e h s t F r t h F c t e o Tr i nity T i o o t t c l o e e e RS 162 F e o F e r 439 Tr i nity t F r r o r w a a Tr i nity F o r o s r o C n t subterrane Tr inity r o r Tr i nity Tr i nity k n n a r n Tr i nity o r l Tr i nity a subterrane b 136 e d k r k P -

Evolution Et Extinction Des Reptiles Marins Au Cours Du Mesozoique

EVOLUTION ET EXTINCTION DES REPTILES MARINS AU COURS DU MESOZOIQUE par Nathalie BARDET * SOMMAIRE Page Résumé, Abstract . 178 Introduction ..................................................................... 179 Matériel et méthode . 181 La notion de reptile marin . 181 Etude systématique . 182 Etude stratigraphique. 183 Méthodes d'analyse. 183 Systématique et phylogénie. 184 Le registre fossile des reptiles marins . 184 Affinités et phylogénie des reptiles marins. 186 Analyses taxinomique et stratigraphique. 187 Testudines (Chelonia) . 187 Squamata, Lacertilia . 191 Squamata, Serpentes. 193 Crocodylia ............................................................... 194 Thalattosauria . 195 Hupehsuchia . 196 Helveticosauroidea . 197 Pachypleurosauroidea . 197 Sauropterygia .... 198 Placodontia. 198 * Laboratoire de Paléontologie des Vertébrés, URA 1761 du CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Case 106,4 Place Jussieu, 75252 Paris cédex 05, France. Mots-clés: Reptiles marins, Tortues, Lézards, Serpents, Crocodiles, Thalattosaures, Hupehsuchiens, Helveticosaures, Pachypleurosaures, Nothosaures, Placodontes, Plésiosaures, Ichthyosaures, Mésozoïque, Evolution, Extinction, Assemblages et Renouvellements fauniques. Key-words: Marine Reptiles, Turtles, Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles, Thalattosaurs, Hupehsuchians, Helveticosaurs, Pachypleurosaurs, Nothosaurs, Placodonts, Plesiosaurs, Ichthyosaurs, Mesozoic, Evolution, Extinction, Faunal Assemblages and Turnovers. Palaeovertebrata. Montpellier. 24 (3-4): 177-283, 13 fig. (Reçu le 4 Juillet 1994, -

University of Nevada Reno Paleoecology of Upper Triassic

University of Nevada Reno Paleoecology of Upper Triassic Bioherms in the Pilot Mountains, Mineral County, West-Central Nevada A tiles is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology by Diane Elinor Cornwall May 1979 University of Nevada Reno ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. James R. Firby for his supervision, support and for his guidance through those difficult "rough spots." Dan Howe was a constant source of interesting ideas and enthusiasm, especially during the early stages of the thesis project. Throughout my research Fred Gustafson and I worked together, he always being an interested and understanding coworker and friend throughout the lonely weeks of research. Dr. Joseph Lintz, Jr. was invaluable in his assistance in procurement of materials and equipment and in his unselfish desire to solve any problem. I thank Dr. Mead for joining my committee. I greatly appreciate those hearty souls who ventured out into the desert with me and braved the hazards and extremes; these include Barbara Foster, Mickie Dunn, Micheal Judge and my parents who spent all their vacations in my field area. I would also like to acknowledge the moral support given by my parents, special and other friends. i n ABSTRAC In the Pilot Mountains, Mineral County, Nevada, up to five horizons of bioherms are present within the top 76 meters of the lower member of the Upper Triassic (Karnian) Luning Formation. These bio herms are located in the carbonate portions of small terrigenous- carbonate rhythms. The biohermal mounds, less than 15 meters high^exhibit four of Wilson's (1975) seven facies. -

Devil's Rock, Hosselkus

25. Devil’s Rock-Hosselkus (Devil’s Rock, Hosselkus Limestone) (Keeler-Wolf and Keeler-Wolf 1975, Keeler-Wolf 1989h, Cheng 1997b) Location This established RNA is on the Shasta-Trinity National Forest. It is centered approximately 24 miles (39 km) NE. of Redding. The area includes all or portions of sects. 21, 22, 23, 26, 27, 28, 32, 33, 34 T35N, R2W and sects. 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 16 T34N, R2W MDBM (40°51'N., 122°06'W.), USGS Devil’s Rock, Goose Gap, and Minnesota Mtn. quads (fig. 51). Ecological subsection – Eastern Klamath Mountains (M261Ai). Target Elements Limestone Ecosystem (unique element), California Black Oak (Quercus kelloggii), and Canyon Live Oak (Quercus chrysolepis) Distinctive Features Limestone Values: A variety of important values can be attributed to the presence of extensive beds of Triassic limestone in the area (fig. 52). These include the localized endemic plant Eupatorium shastensis, wider ranging plants endemic to limestone substrates (e.g., Cheilanthes cooperae, Adiantum capillaris-veneris), localized endemic land snails (Shasta sideband snail [Monodenia Figure 51—Devil’s troglodytes], a category 2 candidate for listing by Rock-Hosselkus the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which means existing information indicates RNA taxa may warrant listing, but substantial biological information necessary to support a proposed rule is lacking), a localized endemic salamander (Shasta Dashed line = salamander [Hydromantes shastae], a State-listed threatened species), a rich Ecological study area; assemblage of Triassic invertebrate fossils (including ammonites, brachiopods, Solid gray line = corals, in all more than 200 species of invertebrates), the best representation of N. RNA Boundary American Triassic marine reptiles (including five species and three genera of icthyosaurs and the only known remains of the order Thalatosauria in the W. -

Paleozoic and Mesozoic Rocks of the Almanor 151 Quadrangle, Plumas

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks of the Almanor 15 1 quadrangle, Plumas County, California by A. S. Jayko Open-file Report 88-757 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey 1988 Menlo Park Text to accompany Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks of the Almanor 15 f quadrangle, Plumas County, California INTRODUCTION The first geologic studies of the Lake Almanor area were published in the late eighteen hundreds by Diller (1892, 1895) and Turner (1898). Subsequent work by McMath (1958, 1966) and by Eldridge Moores and his students including Robinson (1975), D'Allura and others (1977) and Hannah (1980) established much of the stratigraphic and structural framework represented on this geologic map (Figure 1), although significant reinterpretation of some of the earlier recognized features and units has resulted from this investigation. The geology shown on the quadrangle map was mapped during the course of this investigation with the exception of parts of sections 13 and 18, T27N and R8E, which were compiled from Hanna (1980). Field studies were conducted during June to September of 1985, September of 1986, June and July of 1987, and October of 1988. The Almanor quadrangle straddles part of the .geographic and geologic boundary between the Sierra Nevada range on the south and the Cascade Range on the north. The terrain is generally mountainous and heavily forested (by conifers) with elevations ranging from 2,300 feet near Gansner Bar in the southwest corner of the quadrangle to 7,^00 feet on Dyer Mountain in the northeast corner of the quadrangle. -

Article (Published Version)

Article Downslope re-sedimentation from a short-living carbonate platform: Record from the Upper Triassic Hosselkus limestone (Northern California) FUCELLI, Andréa, GOLDING, Martyn, MARTINI, Rossana Abstract Despite their discontinuous occurrence and poor preservation, knowledge about Triassic carbonates from North America has increased considerably during recent years. Their characterization represents a uniqueway to better assess evolution and recovery of the biosphere after the major Permo-Triassic biological crisis in the Panthalassa Ocean. The Eastern Klamath terrane, located in Northern California, is a key terrane due to its geographic position. It is placed halfway between the terranes of the Canadian Cordillera and the Northern Mexico counterparts, both extensively studied and characterized in recent decades, leaving a gap in knowledge along the Pacific coast of the United States. A few kilometers north-east of Redding, Shasta County, California, Upper Triassic carbonates (i.e., the Hosselkus limestone) crop out as a narrow north–south belt about 20 km long, near the artificial reservoir of Lake Shasta. All the accessible localities in this region have been extensively sampled for microfacies and micropaleontological analysis, leading to new insights about the depositional condition and age of the Hosselkus [...] Reference FUCELLI, Andréa, GOLDING, Martyn, MARTINI, Rossana. Downslope re-sedimentation from a short-living carbonate platform: Record from the Upper Triassic Hosselkus limestone (Northern California). Sedimentary Geology, -

Description of the Redding Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE REDDING QUADRANGLE By J. S. Diller. INTRODUCTION. lava and tuff intermingled with the sedimentary hay, stands first among the farm products, with conveniently distinguish it from the plain of the Sac rocks and covering them in many places. The barley next, and small amounts of corn, oats, and ramento Valley proper. The Piedmont Plain is Location and area. The Redding quadrangle whole body of sediments and lavas is penetrated rye. The orchards yield prunes and peaches for for the most part dry, sterile, and usually strewn lies in the northern part of California and is by many dikes and masses of coarse granular plu- shipment, with grapes, pears, almonds, figs, and a with numerous lava fragments, making the roads bounded by meridians 122° and 122° 30'. west tonic rocks, such as granodiorite, gabbro, and ser few apples for home consumption. The genera across it extremely rough, in strong contrast with longitude and parallels 40° 30' and 41° north pentine. This complex of sedimentary and igneous tion of electricity for light and power is a thriving the sand and gravel plain of the Sacramento Valley. latitude. It measures a little over 34 miles from rocks was uplifted, forming the Klamath Moun industry. Fishing deserves mention, and the prop This arises from the fact that the Piedmont Plain north to south and nearly 27 miles from east to tains, at the close of the Jurassic, Erosion agation of fish is of great importance. McCloud is generally underlain by volcanic material in the west, and contains about 905 square miles, a lit and subsidence during the Cretaceous brought River, on account of its large supply of cool water, form of lava flows or agglomerate tuff, and it is tle less than one-fourth the area of Shasta County.