Deviantart Welcomes This Opportunity to Submit Comments in the Above Referenced Request for Comment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alkim Almila Akdag Salah

:: [email protected] :: +90 5326584255 :: SEHIR UNIVERSITY, DRAGOS/ISTANBUL TURKEY ALKIM ALMILA AKDAG SALAH PERSONAL INFORMATION Family name, First name: Alkim Almila, Akdag Salah Researcher unique identifier(s): H-7418-2012 (ResearcherID) Date of birth: 28.08.1975 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alkim_Akdag_Salah; Nationality: Turkish EDUCATION University of California, Los Angeles, California Ph.D. Art History, September 2008 Thesis: ‘Discontents of Computer Art: A Discourse Analysis on the Intersection of Arts, Sciences and Technology’ Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey M.A. Art History, June 2001 Thesis: ‘A Semiotic Evaluation of Flacons’ Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey B.A. Industrial Product Design, June 1998 St. Georg Austrian High School, Istanbul, Turkey September 1986 – June 1994. RELATED EXPERIENCE Department of Social Informatics, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan Visiting Scholar, 2017-2018. College of Communications, Istanbul Sehir University, Istanbul, Turkey Assoc. Prof, 2016 - today e-Humanities Group, KNAW, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Associate Researcher, 2014 – 2016. Computer Science, Bogazici University, Istanbul, Turkey Adjunct Faculty, 2014 - today New Media Studies, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands Postdoctoral Researcher and Lecturer, 2011-2014. Visual Communication and Design, Sabanci University, Istanbul, Turkey Visiting Scholar, 2011-2013. Virtual Knowledge Studio, KNAW, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Postdoctoral Researcher for -

Submission 80988

artstall TORONTO Submission 80988 executive summary ArtStall Toronto is a unique creative place-making project that provides durable, accessible standardized public toilets that are also aesthetically pleasing, decorated in collaboration with local artists to enhance the character of Toronto’s streets, while addressing perceived problems with both public art and public toilets. On a recent CBC broadcast, a pundit argued that Toronto needs a “Percent for Public Toilets” program 10% ADMIN more than one collecting a “Percent for Public 80% Art.” He complained that the city is awash with sculpture and suggested that Toronto should instead CAPITAL spend developer’s contributions for streetscape 10% improvements on tackling the city’s glaring lack of MAINTENANCE public toilets. But why can’t we combine the two? Toronto’s Percent for Public Art policy encourages both stand-alone artistic works and the artistic treatment of functional civic infrastructure. PERCENT FOR PUBLIC ART PROGRAM 10% ADMIN 65% MAINTENANCE Enter ArtStall Toronto. This program would use 25% ENDOWMENT percent for public art funds to address Toronto’s CAPITAL ongoing lack of public washroom facilities, improving Subway access to the city for residents and tourists. By Streetcar Route applying locally-designed artistic skins to the exteriors of the “Portland Loo” – a recently developed Intersection Pedestrian Volume (Persons) public toilet winning praise for its indestructibility, 7862-10000 ease of maintenance and low cost – Toronto can take 10000-15000 a step toward creating more inclusive, beautiful and dignified streets. 15000-20000 PERCENT FOR 20000-24677 Both public art and public toilets can be controversial. However, merging the two might actually help to ARTSTALL address concerns with both. -

Experience in 2D, CGI, and Flash/Animate TV Productions and Short film

[email protected] www.katebrusk.com Los Angeles, CA 586.306.2436 I’m a story artist with experience in 2D, CGI, and Flash/Animate TV productions and short film. My drive is bringing character-driven stories to Hi! life. I love constrasting personalities and characters with a fiery spirit. This is a resume! Experience Nickelodeon Storyboard Artist May 2016 - present SKILLS Storyboarding for seasons 2,3 & 4 of Shimmer and Shine. Storytelling Reiteration & Revision Responsible for storyboarding a 16-20 page script over 4 Structuring Pipelines weeks. Character Animation Specializing in song sequences, action, and chorography. Communication Tight Deadlines Working closely with Executive Producer and Directors to Putting it to a montage create a cohesive storytelling style. Contributing to reseach and concept for new environments. SOFTWARE Acted as team consultant using 3D models in Storyboard Pro, Storyboard Pro, and developed effecient internal workflow. SBP 3d Integration Flash/Animate Photoshop Soup 2 Nuts Storyboard Artist Sept 2013 - Oct 2014 Sketchup Storyboarded seasons 1 & 2 of Astroblast using Flash in a After Effects timeline-based process. Revised scenes on a 24 hour turnaround using producer & EDUCATION director notes. College for Creative Studies Supervised storyboards for 3 episodes, which included BFA in Entertainment Arts handling internal and network notes and overseeing a team May2012 of both on- and offsite artists. Focus in Character and experimental animation Freelance Animation and Design 2012 - 2016 RECOGNITION Worked with a range of clients and studios in a variety of TAFFI Best of Show 2013 styles on commercial projects including Perrier, FOX ADHD, Tour Skechers, Biore, and Cosmic Toast Studios. -

2020 Croner Animation Position Grids.Xlsx

Survey Position Grids STORY / VISUAL DEVELOPMENT ANIMATION Family 200 210 220 230 240 250 260 280 300 Production TV Animation / Character Visual Character Level Story Design / Art Pre-Visualization Modeling Layout Shorts Design Development Animation Direction Executive Management 12 Head of Production Management Generates and Manages the Creates the look Creates characters Creates and Creates sequences of Creates, builds and Creates 3D layouts. Defines, leads and 14 Head of Animation Studio develops story ideas, animation process of and artistic to meet established presents concepts shots that convey the maintains models Translates sketches into 3D executes major 16 Top Creative Executive sequences, an animated deliverables to vision for the and designs for the story through the of story elements, layouts and shot sequences character animation storyboards, television or short film meet the artistic, production, production, including application of traditional including and scenes. May create for productions, elements and production, ensuring creative and including look, character, sets, filmmaking principles in characters, sets and scenes. including personality Brief Job Family Descriptions enhancements that the creative aesthetic vision of personality, lighting, props, key a 3D computer graphics environments, Determines camera and animation style. throughout desires, as well as a production. movement, art. Creates plan environment. elements, sets, placement, blocks production. production expression. views and blue structures. characters, -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Apr COF C1:Customer 3/8/2012 3:24 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18APR 2012 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG IFC Darkhorse Drusilla:Layout 1 3/8/2012 12:24 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page April:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/8/2012 11:16 AM Page 1 THE MASSIVE #1 STAR WARS: KNIGHT DARK HORSE COMICS ERRANT— ESCAPE #1 (OF 5) DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: MINUTEMEN #1 DC COMICS MARS ATTACKS #1 IDW PUBLISHING AMERICAN VAMPIRE: LORD OF NIGHTMARES #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO PLANETOID #1 IMAGE COMICS SPAWN #220 SPIDER-MEN #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/8/2012 11:40 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strawberry Shortcake Volume 2 #1 G APE ENTERTAINMENT The Art of Betty and Veronica HC G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Bleeding Cool Magazine #0 G BLEEDING COOL 1 Radioactive Man: The Radioactive Repository HC G BONGO COMICS Prophecy #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Pantha #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Power Rangers Super Samurai Volume 1: Memory Short G NBM/PAPERCUTZ Bad Medicine #1 G ONI PRESS Atomic Robo and the Flying She-Devils of the Pacific #1 G RED 5 COMICS Alien: The Illustrated Story Artist‘s Edition HC G TITAN BOOKS Alien: The Illustrated Story TP G TITAN BOOKS The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen III: Century #3: 2009 G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Harbinger #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Winx Club Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA BOOKS & MAGAZINES Flesk Prime HC G ART BOOKS DC Chess Figurine Collection Magazine Special #1: Batman and The Joker G COMICS Amazing Spider-Man Kit G COMICS Superman: The High Flying History of America‘s Most Enduring -

TAG21 Mag Q1 Web2.Pdf

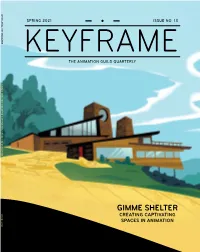

IATSE LOCAL 839 MAGAZINE SPRING 2021 ISSUE NO. 13 THE ANIMATION GUILD QUARTERLY GIMMIE SHELTER: CREATING CAPTIVATING SPACES IN ANIMATION GIMME SHELTER SPRING 2021 CREATING CAPTIVATING SPACES IN ANIMATION FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION BEST ANIMATED FEATURE GLEN KEANE, GENNIE RIM, p.g.a., PEILIN CHOU, p.g.a. GOLDEN GLOBE ® NOMINEE BEST ANIMATED FEATURE “ONE OF THE MOST GORGEOUS ANIMATED FILMS EVER MADE.” “UNLIKE ANYTHING AUDIENCES HAVE SEEN BEFORE.” “★★★★ VIBRANT AND HEARTFELT.” FROM OSCAR®WINNING FILMMAKER AND ANIMATOR GLEN KEANE FILM.NETFLIXAWARDS.COM KEYFRAME QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF THE ANIMATION GUILD, COVER 2 NETFLIX: OVER THE MOON PUB DATE: 02/25/21 TRIM: 8.5” X 10.875” BLEED: 8.75” X 11.125” ISSUE 13 CONTENTS 46 11 AFTER HOURS 18 THE LOCAL FRAME X FRAME Jeremy Spears’ passion TAG committees’ FEATURES for woodworking collective power 22 GIMME SHELTER 4 FROM THE 14 THE CLIMB 20 DIALOGUE After a year of sheltering at home, we’re PRESIDENT Elizabeth Ito’s Looking back on persistent journey the Annie Awards all eager to spend time elsewhere. Why not use your imagination to escape into 7 EDITOR’S an animation home? From Kim Possible’s NOTE 16 FRAME X FRAME 44 TRIBUTE midcentury ambience to Kung Fu Panda’s Bob Scott’s pursuit of Honoring those regal mood, these abodes show that some the perfect comic strip who have passed of animation’s finest are also talented 9 ART & CRAFT architects and interior designers too. The quiet painting of Grace “Grey” Chen 46 SHORT STORY Taylor Meacham’s 30 RAYA OF LIGHT To: Gerard As production on Raya and the Last Dragon evolved, so did the movie’s themes of trust and distrust. -

Women Creating Machinima Jenifer Vandagriff Georgia Institute Of

Women creating Machinima Jenifer Vandagriff Georgia Institute of Technology [email protected] Michael Nitsche Georgia Institute of Technology [email protected] Abstract We interviewed 13 female machinima artists to investigate the appeal of machinima for women. Are there any specific qualities of this game-based production that speak to those women? The research looked at engine use, personal situation of artists and motivation, production processes, and dominant themes in female produced machinima. Our findings indicate that machinima as a form of emergent play opens up promising possibilities for women to engage in game and animation production. Traditional social roles of women are present and remain relevant for machinima production but the accessibility of the tools provides a playground for these filmmakers to explore new genres and technologies and it supports the interest in meaningful engagement and artistic expression stated by participants in the study. We conclude that machinima can serve as a useful tool to explore and improve women’s position in digital media development. Keywords women, machinima, storytelling, media production 1 Women in Machinima Introduction Women comprise only a small fraction of the technical, design, and concept stages of game development. Women constitute approximately 8% for the areas of art, design, and audio. They make up less than 3% in programming (Duffy 2008). Not only are fewer women making decisions about game design, but they also earn substantially less (nearly $10,000) then male colleagues (Duff 2008). While women remain heavily underrepresented in key areas of the game industry workforce, the percentage of female gamers has grown significantly. -

Quantifying the Development of User-Generated Art During 2001–2010

RESEARCH ARTICLE Quantifying the development of user- generated art during 2001±2010 Mehrdad Yazdani1*, Jay Chow2, Lev Manovich3* 1 California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology's Qualcomm Institute, University of California San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, 2 Katana, San Diego, California, United States of America, 3 Computer Science, The Graduate Center at the City University of New York, New York, United States of America * [email protected] (MY); [email protected] (LM) a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 One of the main questions in the humanities is how cultures and artistic expressions change over time. While a number of researchers have used quantitative computational methods to study historical changes in literature, music, and cinema, our paper offers the first quantitative analysis of historical changes in visual art created by users of a social online OPEN ACCESS network. We propose a number of computational methods for the analysis of temporal Citation: Yazdani M, Chow J, Manovich L (2017) development of art images. We then apply these methods to a sample of 270,000 artworks Quantifying the development of user-generated art created between 2001 and 2010 by users of the largest social network for artÐDeviantArt during 2001±2010. PLoS ONE 12(8): e0175350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175350 (www.deviantart.com). We investigate changes in subjects, techniques, sizes, proportions and also selected visual characteristics of images. Because these artworks are classified by Editor: Kewei Chen, Banner Alzheimer's Institute, UNITED STATES their creators into two general categoriesÐTraditional Art and Digital ArtÐwe are also able to investigate if the use of digital tools has had a significant effect on the content and form of Received: June 1, 2016 artworks. -

CG CHARACTER ANIMATOR 253, Rue Saint Denis 75002 Paris, France

Bruno MILLAS CG CHARACTER ANIMATOR 253, rue Saint Denis 75002 Paris, France +33 6 60 73 49 29 +33 1 44 76 06 62 General skills : [email protected] Animator Director - Lead Animator - Animator Director – Screenwriting - Design – Storyboard http://millasbruno.free.fr Layout - Compositing - Modeling - Rigging Professionals Expériences 2010-2012 Studio Hari : Animation director \ Animator \ Director Direction of two teams, one on site and the other in outsourcing on the Series "The Gees”, “The Owl ". Director of one episode "The Gees free falling". 2010 Digital-District : Senior Animator \ Layout Advertising « Badoit ». 2010 BAIACEDEZ : Director \ Animator Institutional movie for « LA ROCHE POSAY ». 2009 Wizz : Director \ Animator director Screenwriting, layout, modeling, rigging, animator director, animator, lighting, fur, render, compositing for the series « OXO ». Director assistant \ Rigging \Animator Advertising « Orange rugby » and game tv trailer « Redsteel2 ». 2008-2009 SolidAnim : Senior Animator Animator and motion-capture editing « Call of Juarez ». 2007-2008 Hérold & family : Senior Animator Feature film « The true story of puss n' boots ». 2007 Méthodes-films : Animation director, technical animation director, team lead Création of animation structure, animation design, bank of movement, actor director and direction of motion capture, animation team supervisor for the game « Skyland ». 2006 BAIACEDEZ : Director \ Animator Advertising « Vichy, Yarden, GSK, Skeen, LA ROCHE POSAY ». 2005-2006 UBISOFT : Senior Animator \ Character TD Teaser « Brother in Arms 3 », « Rayman 4 ». 2002-2005 NEVRAX : Senior Animator \ Character TD Vidéo game « The saga of Ryzom ». 2002 PARTISANT Midi Minuit : Senior Animator Advertising « Danone active ». 1999-2002 DARKWORKS : Director \ Lead CG animator \ Game-play senior animator Lead cinematique and game play animator for the Vidéo game « Alone in the dark 4 ». -

Steven Murdoch Thesis

A new approach for the communication and production of three-dimensional computer assisted character animation Steven Murdoch A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 Swinburne University of Technology P.O. Box 218, Hawthorn, Vic, 3122. Melbourne, Australia Abstract Current methods of communicating knowledge specific to the production of three- dimensional computer assisted character animation are limited. While the quality and complexity of character animation has increased over recent decades, there has been little advancement in the ways of making deep artistic and technical production knowledge explicit and sharable to aspiring character animators. In this research Agent-Oriented Software Engineering was applied as a theoretical framework to discuss the components of the animation environment as notions of agency and requirements. The graphical modelling method Agent-Oriented Goal Modelling was then leveraged to design a conceptual goal model of an explicit, simple language system design for the production of three-dimensional computer animation. This Mk I (mark one) Goal Model was applied within an animation project that pursued the collaborative production of three short undergraduate student films. Through the analysis of quantitative and qualitative project data, the Mk I Goal Model was found to communicate production practice and process. At this time areas for improvement were identified concerning the goal model’s granularity, the communication of different types of quality, and the evaluation of requirement achievement. Based on this data, a second simplified conceptual Mk II (mark two) Goal Model was designed that explicitly incorporated Primary and Emotional system requirements. This Mk II Goal Model was then evaluated across a series of short, independent undergraduate student character animation projects. -

Download Your Free Digital Copy of the June 2018 Special Print Edition of Animationworld Magazine Today

ANIMATIONWorld GOOGLE SPOTLIGHT STORIES | SPECIAL SECTION: ANNECY 2018 MAGAZINE © JUNE 2018 © PIXAR’S INCREDIBLES 2 BRAD BIRD MAKES A HEROIC RETURN SONY’S NINA PALEY’S HOTEL TRANSYLVANIA 3 BILBY & BIRD KARMA SEDER-MASOCHISM GENNDY TARTAKOVSKY TAKES DREAMWORKS ANIMATION A BIBLICAL EPIC YOU CAN JUNE 2018 THE HELM SHORTS MAKE THEIR DEBUT DANCE TO ANiMATION WORLD © MAGAZINE JUNE 2018 • SPECIAL ANNECY EDITION 5 Publisher’s Letter 65 Warner Bros. SPECIAL SECTION: Animation Ramps Up 6 First-Time Director for the Streaming Age Domee Shi Takes a Bao in New Pixar Short ANNECY 2018 68 CG Global Entertainment Offers a 8 Brad Bird Makes 28 Interview with Annecy Artistic Director Total Animation Solution a Heroic Return Marcel Jean to Animation with 70 Let’s Get Digital: A Incredibles 2 29 Pascal Blanchet Evokes Global Entertainment Another Time in 2018 Media Ecosystem Is on Annecy Festival Poster the Rise 30 Interview with Mifa 71 Golden Eggplant Head Mickaël Marin Media Brings Creators and Investors Together 31 Women in Animation to Produce Quality to Receive Fourth Mifa Animated Products Animation Industry 12 Genndy Tartakovsky Award 72 After 20 Years of Takes the Helm of Excellence, Original Force Hotel Transylvania 3: 33 Special Programs at Annecy Awakens Summer Vacation Celebrate Music in Animation 74 Dragon Monster Brings 36 Drinking Deep from the Spring of Creativity: Traditional Chinese Brazil in the Spotlight at Annecy Culture to Schoolchildren 40 Political, Social and Family Issues Stand Out in a Strong Line-Up of Feature Films 44 Annecy -

Artist Name Work Title Description Year Duration Language Subtitles Disc # Contribution Of

Artist Name Work Title Description Year Duration Language Subtitles Disc # Contribution of Goren, Amit Control A documentary film about the work of the Israeli painter David Reeb and Israeli 2003 49'31'' 36 Digital Art Lab photographer Miki Kartzman. Atay, Fikret Rebels of the Dance This is a video piece that takes place in an ATM booth. Two children get into the 2003 10'55'' None 39 Digital Art Lab booth; they are singing, but the lyrics and the language are not comprehensible. The melodic verse is pleasant to listen to, but it lacks any coherent wording. In spite of this, the synchronization and polyphony (vocal coordination) between them proves their ability to communicate by means of a code. Ligna Group Radioballet - Dispensed In Summer 2003 in Leipzig, a few hundred people met up in a space temporarily 2003 12'31'' None 42 Digital Art Lab Public arranged for the project Radioballett Leipzig. Participants gathered with small radios, or rented them from the organizers, and tuned them to the local independent radio station. At around 6pm, the radio broadcast switched from playing music to a directive, go to the train station. So the group crossed the street to the station and went inside. Directives for behavior were broadcast, interspersed with music. Following the cues, the crowd simultaneously waved, bent over to tie their shoes and danced. Zen Group Derdimi Anla (Understand 2003 6'04'' Hebrew 43 Digital Art Lab Me) Gal, Dani Putter 2004 47 Digital Art Lab Birger, Irina Keeper 2004 None 49 Digital Art Lab Birger, Irina Headache 2004