Jamie S. Davidson and Douglas Kammen1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sambas Sultanate and the Development of Islamic Education

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 8 , No. 11, Nov, 2018, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2018 HRMARS Sambas Sultanate and the Development of Islamic Education Norahida Mohamed, Mohamad Zaidin Mohamad, Fadzli Adam, Mohd Faiz Hakimi Mat Idris, Ahmad Fauzi Hassan, Erwin Mahrus To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i11/4972 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i11/4972 Received: 23 Oct 2018, Revised: 17 Nov 2018, Accepted: 29 Nov 2018 Published Online: 06 Dec 2018 In-Text Citation: (Mohamed et al., 2018) To Cite this Article: Mohamed, N., Mohamad, M. Z., Adam, F., Idris, M. F. H. M., Hassan, A. F., & Mahrus, E. (2018). Sambas Sultanate and the Development of Islamic Education. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(11), 950–957. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 8, No. 11, 2018, Pg. 950 - 957 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 950 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

Planned Deforestation: Forest Policy in Papua | 1

PLANNED DEFORESTATION: FOREST POLICY IN PAPUA | 1 Planned Deforestation Forest Policy in Papua PLANNED DEFORESTATION: FOREST POLICY IN PAPUA | 3 CITATION: Koalisi Indonesia Memantau. 2021. Planned Deforestation: Forest Policy in Papua. February, 2021. Jakarta, Indonesia. Dalam Bahasa Indonesia: Koalisi Indonesia Memantau. 2021. Menatap ke Timur: Deforestasi dan Pelepasan Kawasan Hutan di Tanah Papua. Februari, 2021. Jakarta, Indonesia. Photo cover: Ulet Ifansasti/Greenpeace PLANNED DEFORESTATION: FOREST POLICY IN PAPUA | 3 1. INDONESIAN DEFORESTATION: TARGETING FOREST-RICH PROVINCES Deforestation, or loss of forest cover, has fallen in Indonesia in recent years. Consequently, Indonesia has received awards from the international community, deeming the country to have met its global emissions reduction commitments. The Norwegian Government, in line with the Norway – Indonesia Letter of Intent signed during the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono presidency, paid USD 56 million,1 equivalent to IDR 812 billion, that recognizes Indonesia’s emissions achievements.2 Shortly after that, the Green Climate Fund, a funding facility established by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), agreed to a funding proposal submitted by Indonesia for USD 103.8 million3, equivalent to IDR 1.46 trillion, that supports further reducing deforestation. 923,050 923,550 782,239 713,827 697,085 639,760 511,319 553,954 508,283 494,428 485,494 461,387 460,397 422,931 386,328 365,552 231,577 231,577 176,568 184,560 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 Figure 1. Annual deforestation in Indonesia from 2001-2019 (in hectares). Deforestation data was obtained by combining the Global Forest Change dataset from the University of Maryland’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) and land cover maps from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF). -

Reconciling Economic Growth with Emissions Reductions

In cooperation with: Financial Cooperation (KfW) This module focuses on the implementation of REDD+ ‘on the ground’. It aims to demonstrate the viability of a pro-poor REDD mechanism in Kalimantan to decision-makers and stakeholders, is the German Development Bank, thus enriching the national and international debate on REDD+ acting on behalf of the German Government. It with practical implementation experience. KfW uses a district carries out cooperation projects with developing based approach in order to prepare selected pilot areas for national and emerging countries. In Indonesia, KfW’s and international carbon markets. KfW finances measures to long-standing cooperation started in 1962 with achieve readiness in three districts of Kalimantan (Kapuas Hulu, its local office in Jakarta established in 1998. KfW Malinau, Berau), realizes an investment programme for REDD has been actively engaged in the forestry sector demonstration activities and develops an innovative and fair since 2008, as mandated by the Federal Ministry incentive payment scheme. for Economic Cooperation and Development Components of the FORCLIME Financial Cooperation (FC) (BMZ) and the Federal Ministry for the Module: Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMUB). Our forestry portfolio includes • Livelihood: improvement of livelihood and capacity building. REDD+, Biodiversity and Integrated Watershed • Forest ecosystem management: forest ecosystem assesment, Management, Ecosystem Restoration and an support to FSC certification, best practice of concession ASEAN Regional Programme. management, qualified data and information. • Documentation and dissemination of lessons learned. • Carbon management: carbon accounting, remote sensing, GIS, and terestrial inventory, benefit sharing financing / carbon Where we work payment. • Carbon management and land use planning: carbon monitoring at site and district level, support communities to conduct .Tanjung Selor carbon monitoring. -

Strengthening the Disaster Resilience of Indonesian Cities – a Policy Note

SEPTEMBER 2019 STRENGTHENING THE Public Disclosure Authorized DISASTER RESILIENCE OF INDONESIAN CITIES – A POLICY NOTE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Background Urbanization Time to ACT: Realizing Paper Flagship Report Indonesia’s Urban Potential Public Disclosure Authorized STRENGTHENING THE DISASTER RESILIENCE OF INDONESIAN CITIES – A POLICY NOTE Urban floods have significant impacts on the livelihoods and mobility of Indonesians, affecting access to employment opportunities and disrupting local economies. (photos: Dani Daniar, Jakarta) Acknowledgement This note was prepared by World Bank staff and consultants as input into the Bank’s Indonesia Urbanization Flagship report, Time to ACT: Realizing Indonesia’s Urban Potential, which can be accessed here: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31304. The World Bank team was led by Jolanta Kryspin-Watson, Lead Disaster Risk Management Specialist, Jian Vun, Infrastructure Specialist, Zuzana Stanton-Geddes, Disaster Risk Management Specialist, and Gian Sandosh Semadeni, Disaster Risk Management Consultant. The paper was peer reviewed by World Bank staff including Alanna Simpson, Senior Disaster Risk Management Specialist, Abigail Baca, Senior Financial Officer, and Brenden Jongman, Young Professional. The background work, including technical analysis of flood risk, for this report received financial support from the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) through the World Bank Indonesia Sustainable Urbanization (IDSUN) Multi-Donor Trust Fund. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. ii STRENGTHENING THE DISASTER RESILIENCE OF INDONESIAN CITIES – A POLICY NOTE THE WORLD BANK Table of Contents 1. -

Parental Expectations and Young People's Migratory

Jurnal Psikologi Volume 44, Nomor 1, 2017: 66 - 79 DOI: 10.22146/jpsi.26898 Parental Expectations and Young People’s Migratory Experiences in Indonesia Wenty Marina Minza1 Center for Indigenous and Cultural Psychology Faculty of Psychology Universitas Gadjah Mada Abstract. Based on a one-year qualitative study, this paper examines the migratory aspirations and experiences of non-Chinese young people in Pontianak, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. It is based on two main questions of migration in the context of young people’s education to work transition: 1) How do young people in provincial cities perceive processes of migration? 2) What is the role of intergenerational relations in realizing these aspirations? This paper will describe the various strategies young people employ to realize their dreams of obtaining education in Java, the decisions made by those who fail to do so, and the choices made by migrants after the completion of their education in Java. It will contribute to a body of knowledge on young people’s education to work transitions and how inter-generational dynamics play out in that process. Keywords: intergenerational relation; migratory aspiration; youth Internal1 migration plays a key role in older generation in Pontianak generally mapping mobility patterns among young associate Java with ideas of progress, people, as many young people continue to opportunities for social mobility, and the migrate within their home country (Argent success of inter-generational reproduction & Walmsley, 2008). Indonesia is no excep- or regeneration. Yet, migration involves tion. The highest participation of rural various negotiation processes that go urban migration in Indonesia is among beyond an analysis of push and pull young people under the age of 29, mostly factors. -

The North Kalimantan Communist Party and the People's Republic Of

The Developing Economies, XLIII-4 (December 2005): 489–513 THE NORTH KALIMANTAN COMMUNIST PARTY AND THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA FUJIO HARA First version received January 2005; final version accepted July 2005 In this article, the author offers a detailed analysis of the history of the North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP), a political organization whose foundation date itself has been thus far ambiguous, relying mainly on the party’s own documents. The relation- ships between the Brunei Uprising and the armed struggle in Sarawak are also referred to. Though the Brunei Uprising of 1962 waged by the Partai Rakyat Brunei (People’s Party of Brunei) was soon followed by armed struggle in Sarawak, their relations have so far not been adequately analyzed. The author also examines the decisive roles played by Wen Ming Chyuan, Chairman of the NKCP, and the People’s Republic of China, which supported the NKCP for the entire period following its inauguration. INTRODUCTION PRELIMINARY study of the North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP, here- after referred to as “the Party”), an illegal leftist political party based in A Sarawak, was published by this author in 2000 (Hara 2000). However, the study did not rely on the official documents of the Party itself, but instead relied mainly on information provided by third parties such as the Renmin ribao of China and the Zhen xian bao, the newspaper that was the weekly organ of the now defunct Barisan Sosialis of Singapore. Though these were closely connected with the NKCP, many problems still remained unresolved. In this study the author attempts to construct a more precise party history relying mainly on the party’s own information and docu- ments provided by former members during the author’s visit to Sibu in August 2001.1 –––––––––––––––––––––––––– This paper is an outcome of research funded by the Pache Research Subsidy I-A of Nanzan University for the academic year 2000. -

SCHEDULE WEEK#03.Xlsx

WEEK03 NEW CMI SERVICE : SEMARANG - SURABAYA - MAKASSAR - BATANGAS - WENZHOU - SHANGHAI - XIAMEN - SHEKOU - NANSHA- HO CHI MINH ETD ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA VESSEL VOY SEMARANG SURABAYA MAKASSAR BATANGAS Wenzhou SHANGHAI XIAMEN SHEKOU NANSHA HOCHIMINH SITC SEMARANG 2103N 16‐Jan 17‐Jan 19‐Jan 23‐Jan SKIP 28‐Jan 31‐Jan 1‐Feb 2‐Feb 6‐Feb SITC ULSAN 2103N 22‐Jan 23‐Jan 25‐Jan 29‐Jan SKIP 3‐Feb 6‐Feb 7‐Feb 8‐Feb 12‐Feb SITC SHEKOU 2103N 29‐Jan 30‐Jan 1‐Feb 5‐Feb SKIP 10‐Feb 13‐Feb 14‐Feb 15‐Feb 19‐Feb SITC SURABAYA 2103N 5‐Feb 6‐Feb 8‐Feb 12‐Feb SKIP 17‐Feb 20‐Feb 21‐Feb 22‐Feb 26‐Feb SITC SEMARANG 2105N 12‐Feb 13‐Feb 15‐Feb 19‐Feb SKIP 24‐Feb 27‐Feb 28‐Feb 1‐Mar 5‐Mar ** Schedule, Estimated Connecting Vessel, and open closing time are subject to change with or without prior Notice ** WE ALSO ACCEPT CARGO EX : For Booking & Inquiries, Please Contact : Jayapura,Sorong,Bitung,Gorontalo,Pantoloan,Banjarmasin,Samarinda,Balikpapan Customer Service and Outbound Document: ***Transship MAKASSAR Panji / [email protected] / +62 85225501841 / PHONE: 024‐8316699 From Padang,Palembang,Panjang,Pontianak,Banjarmasin,Samarinda,Balikpapan Mey / [email protected] / +62 8222 6645 667 / PHONE : 024 8456433 ***Transship JAKARTA From Pontianak Marketing: ***Transship SEMARANG Lindu / [email protected] / +62 81325733413 / PHONE: 024‐8447797 Equipment & Inbound Document: ALSO ACCEPT CARGO TO DEST : Ganda / [email protected] /+62 81329124361 / Phone : 024‐8315599 Haikou/Fuzhou/Putian/Shantou TRANSSHIP XIAMEN BY FEEDER Keelung/Taichung/Kaohsiung TRANSSHIP SHANGHAI BY FEEDER Finance: Lianyungang, Zhapu Transship Ningbo BY FEEDER Tuti / [email protected] / Phone : 024‐8414150 Fangcheng/Qinzhou TRANSSHIP SHEKOU BY FEEDER HEAD OFFICE : SURABAYA BRANCH : SITE OFFICE : PONTIANAK AGENT Gama Tower, 36th Floor Unit A B C Jembatan Merah Arcade Building 2nd Floor Jln .Gorontalo 3 No.3‐5 PT. -

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

INDONESIA’S TRANSFORMATION and the Stability of Southeast Asia Angel Rabasa • Peter Chalk Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited ProjectR AIR FORCE The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rabasa, Angel. Indonesia’s transformation and the stability of Southeast Asia / Angel Rabasa, Peter Chalk. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. “MR-1344.” ISBN 0-8330-3006-X 1. National security—Indonesia. 2. Indonesia—Strategic aspects. 3. Indonesia— Politics and government—1998– 4. Asia, Southeastern—Strategic aspects. 5. National security—Asia, Southeastern. I. Chalk, Peter. II. Title. UA853.I5 R33 2001 959.804—dc21 2001031904 Cover Photograph: Moslem Indonesians shout “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) as they demonstrate in front of the National Commission of Human Rights in Jakarta, 10 January 2000. Courtesy of AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE (AFP) PHOTO/Dimas. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Maritta Tapanainen © Copyright 2001 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, -

(COVID-19) Situation Report

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) World Health Organization Situation Report - 64 Indonesia 21 July 2021 HIGHLIGHTS • As of 21 July, the Government of Indonesia reported 2 983 830 (33 772 new) confirmed cases of COVID-19, 77 583 (1 383 new) deaths and 2 356 553 recovered cases from 510 districts across all 34 provinces.1 • During the week of 12 to 18 July, 32 out of 34 provinces reported an increase in the number of cases while 17 of them experienced a worrying increase of 50% or more; 21 provinces (8 new provinces added since the previous week) have now reported the Delta variant; and the test positivity proportion is over 20% in 33 out of 34 provinces despite their efforts in improving the testing rates. Indonesia is currently facing a very high transmission level, and it is indicative of the utmost importance of implementing stringent public health and social measures (PHSM), especially movement restrictions, throughout the country. Fig. 1. Geographic distribution of cumulative number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Indonesia across the provinces reported from 15 to 21 July 2021. Source of data Disclaimer: The number of cases reported daily is not equivalent to the number of persons who contracted COVID-19 on that day; reporting of laboratory-confirmed results may take up to one week from the time of testing. 1 https://covid19.go.id/peta-sebaran-covid19 1 WHO Indonesia Situation Report - 64 who.int/indonesia GENERAL UPDATES • On 19 July, the Government of Indonesia reported 1338 new COVID-19 deaths nationwide; a record high since the beginning of the pandemic in the country. -

North Kalimantan Province Has Five Districts and One • Malinau : 226.322 Inhabitants City

PROVINCE OVERVIEW INDONESIA INDUSTRIAL ESTATES DIRECTORY 2018-2019 North Kalimantan Province Beautiful beach of Derawan orth Kalimantan is located in the northern part of Kalimantan Island. The capital city is Tanjung Selor. Basic Data North Kalimantan borders the Malaysian states of NSabah to the north and Sarawak to the west, and the Capital: Tanjung Selor Indonesian province of East Kalimantan to the south. North Kalimantan is the newest province of Indonesia, Major Cities: created on the 25th of October 2012. Administratively, • Tarakan : 239.973 inhabitants North Kalimantan province has five districts and one • Malinau : 226.322 inhabitants city. Its population of 738.163 is spread over an area of • Bulongan : 140.567 inhabitants 75.467,70 km2. • Nunukan : 62.460 inhabitants In developing the province, the government has • Tana Tidung : 22.841 inhabitants set the vision to ”harmonize in Pluralism to achieve an 2 independent, safe, peaceful, clean and proud North Size of Province: 72.567.49 km Kalimantan by 2020“. This vision is to be achieved by reducing poverty and unemployment, increasing economic Population: competitiveness of the agroindustry, tourism, and (1) Province : 738.163 inhabitants sustainable mining and by enhancing North Kalimantan’s (2015) human resources quality to become smarter, nobler, more (2) Province Capital : 42.231 (2012) skillful, and highly competitive. Moreover, the government Salary (2018): wants to develop the province’s infrastructure to enhance The provincial monthly minimum wage : interregional connectivity within Indonesia and with USD 189,62. neighboring countries. The dominant economic sectors of North Kalimantan are mining, agriculture, construction, and the processing industry. In mining, North Kalimantan has many products Educational Attainment such as, crude oil, natural gas, coal, and gold, while for Never attending agriculture, the products produced in North Kalimantan DIPLOMA school % are rice, corn, soy, and livestock. -

Captures Asean

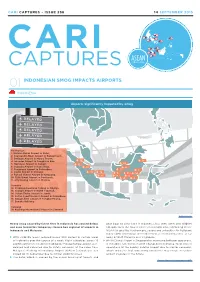

CARI CAPTURES • ISSUE 236 14 SEPTEMBER 2015 CARI ASEAN CAPTURES REGIONAL 01 INDONESIAN SMOG IMPACTS AIRPORTS INDONESIA Airports Significantly Impacted by Smog DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED Kalimantan 1. Melalan Melak Airport in Kutai, 2. Syansyudin Noor Airport in Banjarmasin, 3. Beringin Airport in Muara Teweh, 4. Iskandar Airport in Pangkalan Bun 13 11 5. Haji Asan Airport in Sampit, 12 18 6. Supadio Airport in Kubu Raya, 14 8 7. Pangsuma Airport in Putussibau, 7 1 8. Susilo Airport in Sintang, 15 16 6 3 10 9. Rahadi Usman Airport in Ketapang, 17 9 5 10. Tjilik Riwut Airport in Pontianak, 4 2 11. Atty Besing Airport in Malinau. Sumatra 12. Ferdinand Lumban Tobing in Sibolga, 13. Silangit Airport in North Tapanuli, 14. Sultan Thaha Airport in Jambi, 15. Sultan Syarif Kasim II Airport in Pekanbaru, 16. Depati Amir Airport in Pangkal Pinang, 17. Bangka Belitung Sarawak 18. Kuching International Airport in Sarawak Antara News Heavy smog caused by forest fires in Indonesia has caused delays peat bogs to clear land in Indonesia, has seen some 400 wildfire and even forced the temporary closure two regional of airports in hotspots over the course of the past month alone according to the Indonesia and Malaysia. NOAA-18 satellite; furthermore, severe and unhealthy Air Pollutant Index (API) recordings were observed at several locations as far With visibility levels reduced below 800 meters in certain areas away as East Malaysia and Singapore of Indonesia over the course of a week, flight schedules across 16 Whilst Changi Airport in Singapore -

Laporan Kinerja Badan Geologi Tahun 2014

LAPORAN KINERJA BADAN GEOLOGI TAHUN 2014 BADAN GEOLOGI KEMENTERIAN ENERGI DAN SUMBER DAYA MINERAL Tim Penyusun: Oman Abdurahman - Priatna - Sofyan Suwardi (Ivan) - Rian Koswara - Nana Suwarna - Rusmanto - Bunyamin - Fera Damayanti - Gunawan - Riantini - Rima Dwijayanti - Wiguna - Budi Kurnia - Atep Kurnia - Willy Adibrata - Fatmah Ughi - Intan Indriasari - Ahmad Nugraha - Nukyferi - Nia Kurnia - M. Iqbal - Ivan Verdian - Dedy Hadiyat - Ari Astuti - Sri Kadarilah - Agus Sayekti - Wawan Bayu S - Irwana Yudianto - Ayi Wahyu P - Triyono - Wawan Irawan - Wuri Darmawati - Ceme - Titik Wulandari - Nungky Dwi Hapsari - Tri Swarno Hadi Diterbitkan Tahun 2015 Badan Geologi Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral Jl. Diponegoro No. 57 Bandung 40122 www.bgl.esdm.go.id Pengantar Geologi merupakan salah satu pendukung penting dalam program pembangunan nasional. Untuk program tersebut, geologi menyediakan informasi hulu di bidang En- ergi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (ESDM). Di samping itu, kegiatan bidang geologi juga menyediakan data dan informasi yang diperlukan oleh berbagai sektor, seperti mitigasi bencana gunung api, gerakan tanah, gempa bumi, dan tsunami; penataan ruang, pemba- ngunan infrastruktur, pengembangan wilayah, pengelolaan air tanah, dan penyediaan air bersih dari air tanah. Pada praktiknya, pembangunan kegeologian di tahun 2014 masih menghadapi beber- apa isu strategis berupa peningkatan kualitas hidup masyarakat Indonesia mencapai ke- hidupan yang sejahtera, aman, dan nyaman mencakup ketahanan energi, lingkungan dan perubahan iklim, bencana alam, tata ruang dan pengembangan wilayah, industri mineral, pengembangan informasi geologi, air dan lingkungan, pangan, dan batas wilayah NKRI (kawasan perbatasan dan pulau-pulau terluar). Ketahanan energi menjadi isu utama yang dihadapi sektor ESDM, sekaligus menjadi yang dihadapi oleh Badan Geologi yang mer- upakan salah satu pendukung utama bagi upaya-upaya sektor ESDM.