Polish-Russian Relations in an Eastern Dimension Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Global Go to Think Tank Index Report1

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons TTCSP Global Go To Think aT nk Index Reports Think aT nks and Civil Societies Program (TTCSP) 1-2019 2018 Global Go To Think aT nk Index Report James G. McGann University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks Part of the International and Area Studies Commons McGann, James G., "2018 Global Go To Think aT nk Index Report" (2019). TTCSP Global Go To Think Tank Index Reports. 16. https://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks/16 2019 Copyright: All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the University of Pennsylvania, Think aT nks and Civil Societies Program. All requests, questions and comments should be sent to: James G. McGann, Ph.D. Senior Lecturer, International Studies Director, Think aT nks and Civil Societies Program The Lauder Institute University of Pennsylvania Email: [email protected] This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks/16 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2018 Global Go To Think aT nk Index Report Abstract The Thinka T nks and Civil Societies Program (TTCSP) of the Lauder Institute at the University of Pennsylvania conducts research on the role policy institutes play in governments and civil societies around the world. Often referred to as the “think tanks’ think tank,” TTCSP examines the evolving role and character of public policy research organizations. -

Individual V. State: Practice on Complaints with the United Nations Treaty Bodies with Regards to the Republic of Belarus

Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus Volume I Collection of articles and documents The present collection of articles and documents is published within the framework of “International Law in Advocacy” program by Human Rights House Network with support from the Human Rights House in Vilnius and Civil Rights Defenders (Sweden) 2012 UDC 341.231.14 +342.7 (476) BBK 67.412.1 +67.400.7 (4Bel) I60 Edited by Sergei Golubok Candidate of Law, Attorney of the St. Petersburg Bar Association, member of the editorial board of the scientific journal “International justice” I60 “Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus”. – Vilnius, 2012. – 206 pages. ISBN 978-609-95300-1-7. The present collection of articles “Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus” is the first part of the two-volume book, that is the fourth publication in the series about international law and national legal system of the republic of Belarus, implemented by experts and alumni of the Human Rights Houses Network‘s program “International Law in Advocacy” since 2007. The first volume of this publication contains original writings about the contents and practical aspects of international human rights law concepts directly related to the Institute of individual communications, and about the role of an individual in the imple- mentation of international legal obligations of the state. The second volume, expected to be published in 2013, will include original analyti- cal works on the admissibility of individual considerations and the Republic of Belarus’ compliance with the decisions (views) by treaty bodies. -

No Justice for Journalists in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia September 2011

No Justice for Journalists in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia September 2011 ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7324 2500 Fax: +44 20 7490 0566 E-mail: [email protected] www.article19.org International Media Support (IMS) Nørregarde 18, 2nd floor 1165 Copenhagen K Denmark Tel: +45 88 32 7000 Fax: +45 33 12 0099 E-mail: [email protected] www.i-m-s.dk ISBN: 978-1-906586-27-0 © ARTICLE 19 and International Media Support (IMS), London and Copenhagen, August 2011 This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 2.5 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, provided you: 1) give credit to ARTICLE 19 and International Media Support (IMS); 2) do not use this work for commercial purposes; 3) distribute any works derived from this publication under a licence identical to this one. To access the full legal text of this licence, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ legalcode. ARTICLE 19 and International Media Support (IMS) would appreciate receiving a copy of any materials in which information from this report is used. This report was written and published within the framework of a project supported by the International Media Support (IMS) Media and Democracy Programme for Central and Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. It was compiled and written by Nathalie Losekoot, Senior Programme Officer for Europe at ARTICLE 19 and reviewed by JUDr. Barbora Bukovskà, Senior Director for Law at ARTICLE 19 and Jane Møller Larsen, Programme Coordinator for the Media and Democracy Unit at International Media Support (IMS). -

Integriertes Küste-Flusseinzugsgebiets-Management an Der Oder/Odra: Hintergrundbericht

IKZM Forschung für ein Integriertes Küstenzonenmanagement Oder in der Odermündungsregion IKZM-Oder Berichte 14 (2005) Integriertes Küste-Flusseinzugsgebiets-Management an der Oder/Odra: Hintergrundbericht Integrated Coastal Area – River Basin Management at the Oder/Odra: Backgroundreport Peene- strom Ostsee Karlshagen Pommersche Bucht Zinnowitz (Oder Bucht) Wolgast Zempin Dziwna Koserow Kolpinsee Ückeritz Bansin HeringsdorfSwina Ahlbeck Miedzyzdroje Usedom Wolin Anklam Swinoujscie Kleines Haff Stettiner (Oder-) Polen Haff Deutschland Wielki Zalew Ueckermünde 10 km Oder/Odra Autoren: Nardine Löser & Agnieszka Sekúñ ci ska Leibniz-Institut für Ostseeforschung Warnemünde Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung ISSN 1614-5968 IKZM-Oder Berichte 14 (2005) Integriertes Küste-Flusseinzugsgebiets-Management an der Oder/Odra: Hintergrundbericht Integrated Coastal Area – River Basin Management at the Oder/Odra: Backgroundreport Zusammengestellt von Compiled by Nardine Löser1 & Agnieszka Sekścińska2 1Leibniz-Institut für Ostseeforschung Warnemünde Seestraße 15, D-18119 Rostock 2Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung Reichpietschufer 50, D-10785 Berlin Rostock, August 2005 Der Bericht basiert auf Vorarbeiten von: Małgorzata Landsberg-Uczciwek - Voivodship Inspectorate for Environmental Protection, Szczecin Martin Adriaanse - UNEP/GPA Kazimierz Furmańczyk - University of Szczecin Stanisław Musielak - University of Szczecin Waldemar Okon - Expertengruppe Mecklenburg-Vorpommern und Wojewodschaft Westpommern, Ministerium für Arbeit, -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Invasions, Insurgency and Interventions: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark 1654 - 1658. A Dissertation Presented by Christopher Adam Gennari to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Christopher Adam Gennari 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Christopher Adam Gennari We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Ian Roxborough – Dissertation Advisor, Professor, Department of Sociology. Michael Barnhart - Chairperson of Defense, Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of History. Gary Marker, Professor, Department of History. Alix Cooper, Associate Professor, Department of History. Daniel Levy, Department of Sociology, SUNY Stony Brook. This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School """"""""" """"""""""Lawrence Martin "" """""""Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Invasions, Insurgency and Intervention: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark. by Christopher Adam Gennari Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 "In 1655 Sweden was the premier military power in northern Europe. When Sweden invaded Poland, in June 1655, it went to war with an army which reflected not only the state’s military and cultural strengths but also its fiscal weaknesses. During 1655 the Swedes won great successes in Poland and captured most of the country. But a series of military decisions transformed the Swedish army from a concentrated, combined-arms force into a mobile but widely dispersed force. -

Diplomatic Dictionary

DIPLOMATIC DICTIONARY A | B | C | D | E | F | I | M | N | P | R | S | T | V A ACCESSION The procedure by which a nation becomes a party to an agreement already in force between other nations. ACCORDS International agreements originally thought to be for lesser subjects than those covered by treaties, but now really treaties by a different name. AMBASSADOR The chief of a diplomatic mission; the ranking official diplomatic representative of a country to the country to which s/he is appointed, and the personal representative of his/her own head of state to the head of state of the host country. Ambassador is capitalized when referring to a specific person (i.e., Ambassador Smith) AMERICAN PRESENCE POSTS (APP) A special purpose overseas post with limited staffing and responsibilities, established as a consulate under the Vienna Convention. APPs are located cities outside the capital that are important but do not host a U.S. consulate. Typically these posts do not have any consular services on site, so the APP’s activities are limited or narrowly focused on priorities such as public outreach, business facilitation, and issue advocacy. Examples of American Presence Posts include: Bordeaux, France; Winnipeg, Canada; Medan, Indonesia and Busan, Korea. ARMS CONTROL Arms Control refers to controlling the amount or nature of weapons-such as the number of nuclear weapons or the nature of their delivery vehicles -- a specific nation is allowed to have at a specific time. ATTACHÉ An official assigned to a diplomatic mission or embassy. Usually, this person has advanced expertise in a specific field, such as agriculture, commerce, or the military. -

Stanisław Jan Jabłonowski

Stanisław Jan Jabłonowski From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Stanisław Jan Jabłonowski (1634–1702) was a Polish Stanisław Jan Jabłonowski nobleman, magnate, outstanding military commander. He was the son of the Lord Sword-Bearer Jan Jabłonowski and Anna Ostroróg (Ostrorogow). He married Marianna Kazanowska in 1658. He became the Grand Guardian of the Crown in 1660, the Grand Camp Leader of the Crown in 1661, the voivode of Ruthenian Voivodship in 1664, Field Crown Hetman in 1676, Great Crown Hetman in 1682 and castellan of Kraków in 1692. He was also the Starost of Kamieniec Podolski, Żydaczów, Sierpc, Winnica, Świecie, Korsuń, Czehryń, Biała Cerkiew, Bohusław, Busko-Zdrój, Międzyrzec Podlaski, Mościsk, Błonie, Janów Lubelski and Nisko. He participated in the War with Sweden during The Noble Jabłonowski Deluge, then with the Family Cossacks and Muscovy. He took part in the Chocim campaign of 1673 and participated in the Vienna Monument of Hetman Stanislaw expedition of 1683. He led Coat of Jan Jabłonowski erected by the right wing of Polish Arms grateful inhabitants of Lwów. cavalry forces at the Battle of Vienna. He also stopped Prus the Tatars at Lwów in 1695. III In 1692 Stanisław built the stronghold and the neighbouring Jan Jabłonowski Parents town of Okopy Świętej Trójcy. Anna Ostroróg He was a candidate for the Polish throne in 1696. During the Consorts Marianna Kazanowska election, he supported August II, later in opposition to the King. with Marianna Kazanowska The Princely House of Jablonowski by Jan Stanisław (http://www.geocities.com/rafalhm/Jab.html) -

Evolution of Belarusian-Polish Relations at the Present Stage: Balance of Interests

Журнал Белорусского государственного университета. Международные отношения Journal of the Belarusian State University. International Relations UDC 327(476:438) EVOLUTION OF BELARUSIAN-POLISH RELATIONS AT THE PRESENT STAGE: BALANCE OF INTERESTS V. G. SHADURSKI а aBelarusian State University, Nezavisimosti avenue, 4, Minsk, 220030, Republic of Belarus The present article is dedicated to the analysis of the Belarusian-Polish relations’ development during the post-USSR period. The conclusion is made that despite the geographical neighborhood of both countries, their cultural and historical proximity, cooperation between Minsk and Warsaw didn’t comply with the existing capacity. Political contradictions became the reason for that, which resulted in fluctuations in bilateral cooperation, local conflicts on the inter-state level. The author makes an attempt to identify the main reasons for a low level of efficiency in bilateral relations and to give an assessment of foreign factors impact on Minsk and Warsaw policies. Key words: Belarusian-Polish relations; Belarusian foreign policy; Belarusian and Polish diplomacy; historical policy. ЭВОЛЮЦИЯ БЕЛОРУССКО-ПОЛЬСКИХ ОТНОШЕНИЙ НА СОВРЕМЕННОМ ЭТАПЕ: ПОИСК БАЛАНСА ИНТЕРЕСОВ В. Г. ШАДУРСКИЙ 1) 1)Белорусский государственный университет, пр. Независимости, 4, 220030, г. Минск, Республика Беларусь В представленной публикации анализируется развитие белорусско-польских отношений на протяжении периода после распада СССР. Делается вывод о том, что, несмотря на географическое соседство двух стран, их культурную и историческую близость, сотрудничество Минска и Варшавы не соответствовало имеющемуся потенциалу. При- чиной тому являлись политические разногласия, следствием которых стали перепады в двухстороннем взаимодей- ствии, частые конфликты на межгосударственном уровне. Автор пытается выяснить основные причины невысокой эффективности двусторонних связей, дать оценку влияния внешних факторов на политику Минска и Варшавы. -

Belarus Headlines XIII .Pub

Office for a Democratic Belarus Belarus Headlines Issue XIII July 11 – August 31, 2007 PACE RAPPORTEUR ON BELARUS ANDREA RIGONI: THERE IS NO NEUTRAL THINKING ON THE SITUATION IN BELARUS Interview with PACE special and that rapporteur on Belarus is the (series: Face to face with reason Europe) why it Office for a Democratic Italian deputy of the Parlia- isn’t Belarus mentary Assembly of the easy to Council of Europe Andrea set a Rigoni was appointed Rap- dialogue Inside this porteur on Belarus in the Po- about it. issue litical Affairs Committee in February 2007. Since then he ODB: has had several meetings with What is Interview with 1-2 Belarusian officials in Rome then the Andrea Rigoni and Strasbourg. country it is focused on the opinion like? exchange for the elabora- Politics and Society 2-4 Office for a Democratic Bel- tion of the report within the arus: Mr.Rigoni, you seem to AR: I am currently building my personal idea on Bela- Political Committee of the be the first Rapporteur on the Council of Europe. situation in Belarus with rus through the hearings in Economics 4-7 whom the Belarusian officials the Sub-Committee for ODB: Will you cooperate are ready to have a regular Belarus, through the meet- only with the Belarusian dialogue. Your colleagues ings I am having on this authorities for your re- Announcements 7 Andres Herkel (CoE) and issue and even more with port? When will your re- Adrian Severin (UN) have the help of the visits that I port be ready? never been able to visit Bela- will carry out to Minsk. -

In Annual Speeches of the Republic of Poland Ministers of Foreign Affairs After 2001

Przegląd Strategiczny 2017, nr 10 Piotr POCHYŁY DOI : 10.14746/ps.2017.1.12 University of Zielona Góra THE CONCEPT OF “SECURITY” IN ANNUAL SPEECHES OF THE REPUBLIC OF POLAND MINISTERS OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AFTER 2001 The purpose of the publication is to present how the concept of security has been de- fined in annual speeches of Poland’s foreign ministers after the 9/11 attacks in 2001. Research problem: the impact of the international situation on ways of ensuring Po- land’s security in the annual speeches of Polish foreign ministers. Apart from the as- pect of classically understood security, the analysis also covers modern categories of security that is economic, public, ecological, energy or food security. The temporal range is from 2001 to 2017. Following the definition in the Polish Language Diction- ary published by PWN I define “security” as “the state of non-threat” (Bezpieczeństwo, 2017). * * * Every year foreign ministers of Poland give their annual speeches – officially known as the Information of the Foreign Minister on the goals of foreign policy, in which they define priorities, characterize challenges, and present corrections to the policy. Sometimes it is just an ordinary fulfilment of the obligation, which does not provoke greater conflicts or reflections and is presented in the nearly empty hall, but since 2010, after the plane crash near Smolensk, there have been very exciting debates connected with disputes in the Parliament (speeches given by Radosław Sikorski between 2011–2014), also in connection to responsibility for state security. The speeches which were urgent responses to events in the world (Sikorski, 2014) and the ones that were given when new governments came to power: (Cimoszewicz, 2002; Meller, 2006; Sikorski, 2008; Sikorski, 2012; Waszczykowski, 2016) will be particularly relevant to the search for answers to the research problem because apart from presenting current issues the ministers were obliged to discuss four-year for- eign policy assumptions. -

The Search for a Negotiated Settlement of the Vietnam War

INDOCHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH Ji/t INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY The Search for a Negotiated Settlement of the Vietnam War ALLAN E. GOODMAN INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY The Institute of East Asian Studies was established at the University of Califor nia, Berkeley, in the fall of 1978 to promote research and teaching on the cultures and societies of China, Japan, and Korea. It amalgamates the following research and instructional centers and programs: Center for Chinese Studies, Center for Japanese Studies, Center for Korean Studies, Group in Asian Studies, East Asia National Resource Center, and Indochina Studies Project. INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES Director: Robert A. Scalapino Associate Director: John C. Jamieson Assistant Director: Ernest J. Notar Executive Committee: Joyce K. Kallgren Herbert P. Phillips John C. Jamieson Irwin Scheiner Michael C. Rogers Chalmers Johnson Robert Bellah Frederic Wakeman, Jr. CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Chair: Joyce K. Kallgren CENTER FOR JAPANESE STUDIES Chair: Irwin Scheiner CENTER FOR KOREAN STUDIES Chair: Michael C. Rogers GROUP IN ASIAN STUDIES Chair: Lowell Dittmer EAST ASIA NATIONAL RESOURCE CENTER Director: John C. Jamieson INDOCHINA STUDIES PROJECT Director: Douglas Pike The Search for a Negotiated Settlement of the Vietnam War A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720 The Indochina Monograph series is the newest of the several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the China Research Monograph series, whose first title appeared in 1967, the Korea Research Monograph series, the Japan Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. -

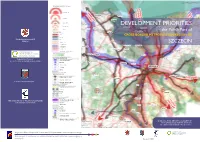

Development Priorities

HIERARCHICAL STRUCTURE OF THE CITIES KOPENHAGA SZTOKHOLSZTOKHOLM Lubmin METROPOLITAN HAMBURG OSLO LUBEKA Greifswald Zinnowitz REGIONAL Wolgast M Dziwnów GDAŃSKRYGA SUBREGIONAL Loitz DEVELOPMENT PRIORITIES SUPRA-LOCAL Heringsdorf Kamień Gutzkow Międzyzdroje Jarmen Pomorski LOCAL Świnoujście the Polish Part of MAIN CONNECTIONS Anklam ROAD CROSS BORDER METROPOLITAN REGION OF Wolin RAILWAY Golczewo ZACHODNIOPOMORSKIE WATER REGION Ducherow NATIONAL ROAD SZCZECIN REGIONAL ROAD Uckermunde Nowe Warpno VIA HANSEATICA Altentreptow Eggesin CETC-ROUTE 65 Friedland Ferdindndshof INTERNATIONAL CYCLING TRAILS Nowogard Torgelow PROTECTED NATURAL AREAS Neubrandenburg Police INLAD AND SEA INFRASTRUCTURE Goleniów THE ASSOCIATION OF SEAPORTS WITH BASIC MEANING FOR NATIONAL ECONOMY THE SZCZECIN METROPOLITAN REGION Burg Stargard SEAPORTS Pasewalk Locknitz SMALL SEAPORTS Woldegk HARBOURS Szczecin MARINAS ACCESS CHANNELS AVIATION INFRASTRUCTURE Feldberg Stargard Szczeciński SZCZECIN-GOLENIÓW AIRPORT Prenzlau WARSZAWA COMMUNICATION AIRPORTS THE CITY OF ŚWINOUJŚCIE PROPOSED AIRPORTS, BASED ON EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE Gryfino Gartz RAILWAY NETWORK - PLANNED SZCZECIN METROPOLITAN RAILWAY LOCAL LINE POSSIBLE CONNECTIONS Templin Pyrzyce TRAIN FERRY ECONOMICAL ACTIVITY ZONES Schwedt POZNAŃ MAIN INDUSTRIAL & SERVICE AREAS WROCŁA THE ASSOCIATION OF POLISH MUNICIPALITIES Angermunde EUROREGION POMERANIA MAIN SPATIAL STRUCTURES AGRICULTURAL Chojna Trzcińsko Zdrój TOURISTIC W Myślibórz SCIENCE AND EDUCATION Cedynia UNIVERSITIES SCHOOLS WITH BILINGUAL DEPARTMENTS Moryń CONFERENCE