Autocrats Untying Their Hands-Political Prosecution Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China's

C O R P O R A T I O N Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China’s Aerospace Forces Selections from the Inaugural Conference of the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) Edmund J. Burke, Astrid Stuth Cevallos, Mark R. Cozad, Timothy R. Heath For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF340 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9549-7 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface On June 22, 2015, the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), in conjunction with Headquarters, Air Force, held a day-long conference in Arlington, Virginia, titled “Assessing Chinese Aerospace Training and Operational Competence.” The purpose of the conference was to share the results of nine months of research and analysis by RAND researchers and to expose their work to critical review by experts and operators knowledgeable about U.S. -

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

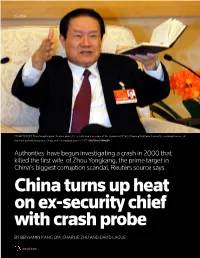

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Introduction This Statement Is Submitted to the U.S.-China

USCC Hearing China’s Military Transition February 7, 2013 Roy Kamphausen Senior Advisor, The National Bureau of Asian Research Introduction This statement is submitted to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to address issues related to the transition to the new top military leadership in China. The statement addresses the composition of the new Central Military Commission, important factors in the selection of the leaders, and highlights salient elements in the backgrounds of specific leaders. The statement also addresses important factors of civil-military relations, including the relationship of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to China’s top political leadership, potential reform of the military-region structure of the PLA, and the likely competition for budget resources. Composition of the China’s New Central Military Commission As expected, new Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping was appointed in November 2012 as the Central Military Commission (CMC) chairman. Additionally, army general Fan Changlong and air force general Xu Qiliang were promoted to positions as vice chairmen of the CMC—Fan from Jinan Military Region commander and Xu from PLA Air Force commander. Other members of the new CMC include General Chang Wanquan, who will become the next Minister of National Defense when that position is confirmed in early spring 2013; General Fang Fenghui, chief of the General Staff Department (GSD), who previously had been Beijing Military Region commander since 2007; General Zhang Yang, director of -

State's Information Control and People's Beliefs in Political Rumors

University of Nevada, Reno Rumor Markets: State’s Information Control and People’s Beliefs in Political Rumors A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science By Chengli Wang Dr. Robert Ostergard/Dissertation Advisor May, 2018 © by Chengli Wang 2018 All Rights Reserved i ABSTRACT In contemporary China, despite heavy censorship, political rumors about corruption and scandals are rampant on the Internet and social media. Contrary to popular intuition, I argue political rumors are prevalent in China because they hold essential functions in maintaining authoritarian resilience: both the government and the people use rumors as an important channel in disseminating their political messages. To test my hypotheses, I conducted an online survey experiment in 2017 in China. I established four models of information exchange that analyze how the state’s information control and a lack of political trust create an underground market mechanism for unauthorized information, which stimulates people purchasing rumors as substitute goods. In information black markets, rumors fill the supply gap of official news that is usually censored by the state or be replaced by propaganda. In gray markets, the state’s information manipulation, such as using rumors to test and guide public opinion, encourages people to take rumors as more accessible and equally reliable sources of news. This research contributes to policy-making in combating political rumors and fake news. Since the inaccessibility and absence of credible information would lead to a proliferation of online rumors, a possible pathway for reducing online rumors is that the government needs to make a “supply-side” reform of official news rather than unilaterally to strike unauthorized information. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

Sopa-Scoopzhoutarget

Friday, August 30, 2013 A3 Beam me up LEADING THE NEWS K-pop stars are embracing hologram COMMERCE Oil giants technology to reach a wider audience > L I F E C 7 banned Unwelcome guest Create your dream home Health headache from new Aquino cancels visit to China: Chic, stylish furniture Migraines can cause INVESTMENT TEAMS TO BE REINED IN Beijing says he was never and accessories for permanent brain damage projects invited in the first place discerning buyers and raise risk of strokes Commerce Ministry targets extravagance by delegations sent Foreign direct investment is a Previously, investment jun- key economic indicator used to kets were believed to be immune > LEA D ING T HE N EWS A 3 > 20-PAG E SPE CIA L REP O R T > WORLD A15 to Hong Kong and Macau to seek investment for their regions gauge officials’ performance, and from the campaign against offi- Beijing makes state ................................................ dozens of delegations from local cial extravagance. overstated the number of partici- His remarks followed the flag- governments flock to Hong Kong The The People’s Daily said busi- energy companies pay Daniel Ren pants and the value of deals ship newspaper’s harsh criticism every year to seek such invest- ness delegations stayed in five- [email protected] phenomenon the price for failing to signed during their promotional on Monday of investment dele- ments. star hotels and invited business- activities. gations travelling to Hong Kong. Yao admitted that the delega- reflects a severe men to expensive restaurants, meet pollution targets The Ministry of Commerce has “They were desperate to get This was the first time that a tions played a positive role in level of spending as much as 1,000 yuan pledged to rein in extravagance abig number of foreign business- Communist Party mouthpiece spurring the nation’s economic (HK$1,260) per head for a break- ............................................... -

A Dynamic Schedule Based on Integrated Time Performance Prediction

2009 First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2009) Nanjing, China 26 – 28 December 2009 Pages 1-906 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP0976H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-4909-5 1/6 TABLE OF CONTENTS TRACK 01: HIGH-PERFORMANCE AND PARALLEL COMPUTING A DYNAMIC SCHEDULE BASED ON INTEGRATED TIME PERFORMANCE PREDICTION ......................................................1 Wei Zhou, Jing He, Shaolin Liu, Xien Wang A FORMAL METHOD OF VOLUNTEER COMPUTING .........................................................................................................................5 Yu Wang, Zhijian Wang, Fanfan Zhou A GRID ENVIRONMENT BASED SATELLITE IMAGES PROCESSING.............................................................................................9 X. Zhang, S. Chen, J. Fan, X. Wei A LANGUAGE OF NEUTRAL MODELING COMMAND FOR SYNCHRONIZED COLLABORATIVE DESIGN AMONG HETEROGENEOUS CAD SYSTEMS ........................................................................................................................12 Wanfeng Dou, Xiaodong Song, Xiaoyong Zhang A LOW-ENERGY SET-ASSOCIATIVE I-CACHE DESIGN WITH LAST ACCESSED WAY BASED REPLACEMENT AND PREDICTING ACCESS POLICY.......................................................................................................................16 Zhengxing Li, Quansheng Yang A MEASUREMENT MODEL OF REUSABILITY FOR EVALUATING COMPONENT...................................................................20 Shuoben Bi, Xueshi Dong, Shengjun Xue A M-RSVP RESOURCE SCHEDULING MECHANISM IN PPVOD