The Production of Choreography Influenced by Works of George

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival 2018 Runs June 20-August 26 with 350+ Performances, Talks, Events, Exhibits, Classes & Works

NATIONAL MEDAL OF ARTS | NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK FOR IMAGES AND MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: Nicole Tomasofsky, Public Relations and Publications Coordinator 413.243.9919 x132 [email protected] JACOB’S PILLOW DANCE FESTIVAL 2018 RUNS JUNE 20-AUGUST 26 WITH 350+ PERFORMANCES, TALKS, EVENTS, EXHIBITS, CLASSES & WORKSHOPS April 26, 2018 (Becket, MA)—Jacob’s Pillow announces the Festival 2018 complete schedule, encompassing over ten weeks packed with ticketed and free performances, pop-up performances, exhibits, talks, classes, films, and dance parties on its 220-acre site in the Berkshire Hills of Western Massachusetts. Jacob’s Pillow is the longest-running dance festival in the United States, a National Historic Landmark, and a National Meal of Arts recipient. Founded in 1933, the Pillow has recently added to its rich history by expanding into a year-round center for dance research and development. 2018 Season highlights include U.S. company debuts, world premieres, international artists, newly commissioned work, historic Festival connections, and the formal presentation of work developed through the organization’s growing residency program at the Pillow Lab. International artists will travel to Becket, Massachusetts, from Denmark, Israel, Belgium, Australia, France, Spain, and Scotland. Notably, representation from across the United States includes New York City, Minneapolis, Houston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Chicago, among others. “It has been such a thrill to invite artists to the Pillow Lab, welcome community members to our social dances, and have this sacred space for dance animated year-round. Now, we look forward to Festival 2018 where we invite audiences to experience the full spectrum of dance while delighting in the magical and historic place that is Jacob’s Pillow. -

Valerie Roche ARAD Director Momix and the Omaha Ballet

Celebrating 50 years of Dance The lights go down.The orchestra begins to play. Dancers appear and there’s magic on the stage. The Omaha Academy of Ballet, a dream by its founders for a school and a civic ballet company for Omaha, was realized by the gift of two remarkable people: Valerie Roche ARAD director of the school and the late Lee Lubbers S.J., of Creighton University. Lubbers served as Board President and production manager, while Roche choreographed, rehearsed and directed the students during their performances. The dream to have a ballet company for the city of Omaha had begun. Lubbers also hired Roche later that year to teach dance at the university. This decision helped establish the creation of a Fine and Performing Arts Department at Creighton. The Academy has thrived for 50 years, thanks to hundreds of volunteers, donors, instructors, parents and above all the students. Over the decades, the Academy has trained many dancers who have gone on to become members of professional dance companies such as: the American Ballet Theatre, Los Angeles Ballet, Houston Ballet, National Ballet, Dance Theatre of Harlem, San Francisco Ballet, Minnesota Dance Theatre, Denver Ballet, Momix and the Omaha Ballet. Our dancers have also reached beyond the United States to join: The Royal Winnipeg in Canada and the Frankfurt Ballet in Germany. OMAHA WORLD HERALD WORLD OMAHA 01 studying the work of August Birth of a Dream. Bournonville. At Creighton she adopted the syllabi of the Imperial Society for Teachers The Omaha Regional Ballet In 1971 with a grant and until her retirement in 2002. -

Singapore Dance Theatre Launches 25 Season with Coppélia

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | JANEK SCHERGEN FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT Melissa Tan Publicity and Advertising Executive [email protected] Joseph See Acting Marketing Manager [email protected] Office: (65) 6338 0611 Fax: (65) 6338 9748 www.singaporedancetheatre.com Singapore Dance Theatre Launches 25th Season with Coppélia 14 - 17 March 2013 at the Esplanade Theatre As Singapore Dance Theatre (SDT) celebrates its 25th Silver Anniversary, the Company is proud to open its 2013 season with one of the most well-loved comedy ballets, Coppélia – The Girl with Enamel Eyes. From 14 – 17 March at the Esplanade Theatre, SDT will mesmerise audiences with this charming and sentimental tale of adventure, mistaken identity and a beautiful life-sized doll. A new staging by Artistic Director Janek Schergen, featuring original choreography by Arthur Saint-Leon, Coppélia is set to a ballet libretto by Charles Nuittier, with music by Léo Delibes. Based on a story by E.T.A. Hoffman, this three-act ballet tells the light-hearted story of the mysterious Dr Coppélius who owns a beautiful life-sized puppet, Coppélia. A village youth named Franz, betrothed to the beautiful Swanilda becomes infatuated with Coppélia, not knowing that she just a doll. The magic and fun begins when Coppélia springs to life! Coppélia is one of the most performed and favourite full-length classical ballets from SDT’s repertoire. This colourful ballet was first performed by SDT in 1995 with staging by Colin Peasley of The Australian Ballet. Following this, the production was revived again in 1997, 2001 and 2007. This year, Artistic Director Janek Schergen will be bringing this ballet back to life with a new staging. -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

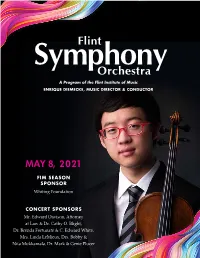

Flint Orchestra

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE to BROOKLYN Judith E

L(30 '11 II. BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Hon. Edward I. Koch, Hon. Howard Golden, Seth Faison, Paul Lepercq, Honorary Chairmen; Neil D. Chrisman, Chairman; Rita Hillman, I. Stanley Kriegel, Ame Vennema, Franklin R. Weissberg, Vice Chairmen; Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Chief Executive Officer; Harry W. Albright, Jr., Henry Bing, Jr., Warren B. Coburn, Charles M. Diker, Jeffrey K. Endervelt, Mallory Factor, Harold L. Fisher, Leonard Garment, Elisabeth Gotbaum, Judah Gribetz, Sidney Kantor, Eugene H. Luntey, Hamish Maxwell, Evelyn Ortner, John R. Price, Jr., Richard M. Rosan, Mrs. Marion Scotto, William Tobey, Curtis A. Wood, John E. Zuccotti; Hon. Henry Geldzahler, Member ex-officio. A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE TO BROOKLYN Judith E. Daykin Executive Vice President and General Manager Richard Balzano Vice President and Treasurer Karen Brooks Hopkins Vice President for Planning and Development IN HONOR OF THE 100th ANNIVERSARY Micheal House Vice President for Marketing and Promotion ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE STAFF OF THE Ruth Goldblatt Assistant to President Sally Morgan Assistant to General Manager David Perry Mail Clerk BROOKLYN BRIDGE FINANCE Perry Singer Accountant Tuesday, November 30, 1982 Jack C. Nulsen Business Manager Pearl Light Payroll Manager MARKETING AND PROMOTION Marketing Nancy Rossell Assistant to Vice President Susan Levy Director of Audience Development Jerrilyn Brown Executive Assistant Jon Crow Graphics Margo Abbruscato Information Resource Coordinator Press Ellen Lampert General Press Representative Susan Hood Spier Associate Press Representative Diana Robinson Press Assistant PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT Jacques Brunswick Director of Membership Denis Azaro Development Officer Philip Bither Development Officer Sharon Lea Lee Office Manager Aaron Frazier Administrative Assistant MANAGEMENT INFORMATION Jack L. -

The BALLET RUSSE De Monte Carlo

The RECORD SHOP Phil Hart, Mgr. presents The BALLET RUSSE de Monte Carlo IN THE PORTLAND AUDITORIUM Thursday, November 16,1944 AT 8:30 P. M. * PLEASE NOTE the following cast changes, due to a leg injury sustained by MR. FRANKLIN. In Le Bourgeois Gentilhornrne Cleonte M. Nicholas MAGALLANES In Gaite Parisienne Tbe Baron M. Nihita TALIN In Danses Concertantes Leon DANIELIAN in place of Frederic FRANKLIN In Rodeo Tbe Champion Roper Mr. Herbert BLISS PROGRAM II. A • "*j 3 • ,. y LE BOURGEOIS GENTILHOMME Choreography by George Balanchine Music by Richard Strauss Scenery and costumes by Eugene Berman Scenery executed by E. B. Dunkel Studios Costumes executed by Karinska, Inc. SERENADE This ballet depicts one episode from Moliere's immortal farce, "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme." A young man, Cleonte, is in love with M. Jourdain's daughter, Luetic M. Jourdain disapproves of the match, as Cleonte is not of noble birth and it is M. Choreography by George BALANCHINE Music by P. I. Tschaikowsky Jourdain's lifetime ambition to shed his middle-class status and rise to aristocracy. Cleonte and his valet, Coviel, impersonate respectively the son of the Great Turk and his ambassador, and under this disguise Cleonte asks for the hand of Lucile. Lucile, at first, unaware of Cleonte's disguise, bitterly resents the wedlock and not Costumes by Jean LURCAT Costumes executed by H. MAHIEU, Inc. until Cleonte raises his mask does she willingly consent. In exchange for the hand of his bride, Cleonte makes M. Jourdain a Mamamouchi—a great dignitary of Turkey—"than which there is nothing more noble in the world," by means of an imposing ceremony. -

The Sleeping Beauty Untouchable Swan Lake In

THE ROYAL BALLET Director KEVIN O’HARE CBE Founder DAME NINETTE DE VALOIS OM CH DBE Founder Choreographer SIR FREDERICK ASHTON OM CH CBE Founder Music Director CONSTANT LAMBERT Prima Ballerina Assoluta DAME MARGOT FONTEYN DBE THE ROYAL BALLET: BACK ON STAGE Conductor JONATHAN LO ELITE SYNCOPATIONS Piano Conductor ROBERT CLARK ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE Concert Master VASKO VASSILEV Introduced by ANITA RANI FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2020 This performance is dedicated to the late Ian Taylor, former Chair of the Board of Trustees, in grateful recognition of his exceptional service and philanthropy. Generous philanthropic support from AUD JEBSEN THE SLEEPING BEAUTY OVERTURE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE UNTOUCHABLE EXCERPT Choreography HOFESH SHECHTER Music HOFESH SHECHTER and NELL CATCHPOLE Dancers LUCA ACRI, MICA BRADBURY, ANNETTE BUVOLI, HARRY CHURCHES, ASHLEY DEAN, LEO DIXON, TÉO DUBREUIL, BENJAMIN ELLA, ISABELLA GASPARINI, HANNAH GRENNELL, JAMES HAY, JOSHUA JUNKER, PAUL KAY, ISABEL LUBACH, KRISTEN MCNALLY, AIDEN O’BRIEN, ROMANY PAJDAK, CALVIN RICHARDSON, FRANCISCO SERRANO and DAVID YUDES SWAN LAKE ACT II PAS DE DEUX Choreography LEV IVANOV Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY Costume designer JOHN MACFARLANE ODETTE AKANE TAKADA PRINCE SIEGFRIED FEDERICO BONELLI IN OUR WISHES Choreography CATHY MARSTON Music SERGEY RACHMANINOFF Costume designer ROKSANDA Dancers FUMI KANEKO and REECE CLARKE Solo piano KATE SHIPWAY JEWELS ‘DIAMONDS’ PAS DE DEUX Choreography GEORGE BALANCHINE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY -

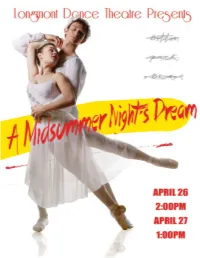

AMND-Program-Final.Pdf

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR KRISTIN KINGSLEY Story & Selected Lyrics from WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Music by FELIX MENDELSSOHN Ballet Mistress STEPHANIE TULEY Music Director/Conductor BRANDON MATTHEWS Production Design SEAN COCHRAN Technical Director ISAIAH BOOTHBY Lighting Design DAVID DENMAN Costume Design NAOMI PRENDERGAST, SUSIE FAHRING, ANN MARCECA, & WANDA RICE WITH STRACCI FOR DANCE NIWOT HIGH SCHOOL AUDITORIUM APRIL 26 2:00PM APRIL 27 1:00PM Longmont Dance Theatre Our mission is simply stated but it is not simple to achieve: we strive to enliven and elevate the human spirit by means of dance, specifically the perfect form of dance known as ballet. A technique of movement that was born in the courts of kings and queens, ballet has survived to this day to become one of the most elegant, most adaptable and most powerful means of human communication. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR BALLET MISTRESS Kristin Kingsley Stephanie Tuley LDT BOARD OF DIRECTORS RESIDENT OPERATION PERSONNEL President Susan Burton Production & Design Vice President Dolores Kingsley Lighting Designer/ David Denman Secretary Marcella Cox Production Stage Manager Members Sean Cochran, Jeanine Hedstrom, Eileen Hickey, Stage Manager Jenn Zavattaro David Kingsley, & Moriah Sullivan Technical Dir./Master Carpenter Isaiah Boothby Ballet Guild Liason Cathy McGovern Scenic Design & Fabrication Sean Cochran with Enigma Concepts and Designs Properties Coordinator Lisa Taft House Manager Marcella Cox RESIDENT COMPANY MANAGEMENT Auditorium Manager Jason Watkins (Niwot HS Auditorium) Willow McGinty Office -

AM Tanny Bio FINAL

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , #AmericanMasters American Masters Tanaquil Le Clercq: Afternoon of a Faun Premieres nationally Friday, June 20, 10-11:30 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Tanaquil Le Clercq Bio Born in Paris in 1929, Tanaquil was the daughter of a French intellectual and a society matron from St. Louis. When Tanny was 3, they moved to New York where Jacques Le Clercq taught romance languages. Tanny began ballet training in New York at age 5, studying with Mikhail Mordkin. She eventually transitioned to the School of American Ballet, which George Balanchine had founded in 1934. Balanchine discovered Tanny as a student there. He cast her as Choleric in The Four Temperaments at the tender age of 15, along with the great prima ballerinas in his company, then called Ballet Society. Before long she was dancing solo roles as a member of Ballet Society, never having danced in the corps de ballet. Some of Balanchine’s most memorable ballets were choreographed on Tanny; notably Symphony in C, La Valse, Concerto Barocco and Western Symphony . She was the original Dew Drop in The Nutcracker. Jerome Robbins was also fascinated with Tanny; famously attributing his enchantment with her unique style of dancing with his decision to join the New York City Ballet and work under Balanchine as both a dancer and choreographer. It was there he created his radical version of Afternoon of a Faun on Tanny. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Finding Aid for Bolender Collection

KANSAS CITY BALLET ARCHIVES BOLENDER COLLECTION Bolender, Todd (1914-2006) Personal Collection, 1924-2006 44 linear feet 32 document boxes 9 oversize boxes (15”x19”x3”) 2 oversize boxes (17”x21”x3”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x4”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x6”) 8 storage boxes 2 storage tubes; 1 trunk lid; 1 garment bag Scope and Contents The Bolender Collection contains personal papers and artifacts of Todd Bolender, dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet director. Bolender spent the final third of his 70-year career in Kansas City, as Artistic Director of the Kansas City Ballet 1981-1995 (Missouri State Ballet 1986- 2000) and Director Emeritus, 1996-2006. Bolender’s records constitute the first processed collection of the Kansas City Ballet Archives. The collection spans Bolender’s lifetime with the bulk of records dating after 1960. The Bolender material consists of the following: Artifacts and memorabilia Artwork Books Choreography Correspondence General files Kansas City Ballet (KCB) / State Ballet of Missouri (SBM) files Music scores Notebooks, calendars, address books Photographs Postcard collection Press clippings and articles Publications – dance journals, art catalogs, publicity materials Programs – dance and theatre Video and audio tapes LK/January 2018 Bolender Collection, KCB Archives (continued) Chronology 1914 Born February 27 in Canton, Ohio, son of Charles and Hazel Humphries Bolender 1931 Studied theatrical dance in New York City 1933 Moved to New York City 1936-44 Performed with American Ballet, founded by