Sovereignty, Modernity and Urban Space: Everyday Socio-Spatial Practices in Karachi’S Inner City Quarters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Detail of Registered Travel Agents in Jalandhar District Sr.No

Detail of Registered Travel Agents in Jalandhar District Sr.No. Licence No. Name of Travel Agent Office Name & Address Home Address Licence Type Licence Issue Date Till Which date Photo Licence is Valid 1 2 3 4 5 1 1/MC1/MA Sahil Bhatia S/o Sh. M/s Om Visa, Shop R/o H.No. 57, Park Avenue, Travel Agency Consultancy Ticekting Agent 9/4/2015 9/3/2020 Manoj Bhatia No.10, 12, AGI Business Ladhewali Road, Jalandhar Centre, Near BMC Chowk, Garha Road, Jalandhar 2 2/MC1/MA Mr. Bhavnoor Singh Bedi M/s Pyramid E-Services R/o H.No.127, GTB Avenue, Jalandhar Travel Agent Coaching Consultancy Ticekting Agent 9/10/2015 9/9/2020 S/o Mr. Jatinder Singh Pvt. Ltd., 6A, Near Old Institution of Bedi Agriculture Office, Garha IELTS Road, Jalandhar 3 3/MC1/MA Mr.Kamalpreet Singh M/S CWC Immigration Sco 26, Ist to 2nd Floor Crystal Plaza, Travel Agency 12/21/2015 12/20/2020 Khaira S/o Mr. Kar Solution Choti Baradari Pase-1 Garha Road , Jalandhar 4 4/MC1/MA Sh. Rahul Banga S/o Late M/S Shony Travels, 2nd R/o 133, Tower Enclave, Phase-1, Travel Agent Ticketing Agent 12/21/2015 6/17/2023 Sh. Durga Dass Bhanga Floor, 190-L, Model Jalandhar Town Market, Jalandhar 5 5/MC1/MA Sh.Jaspla Singh S/o Sh. M/S Cann. World Sco-307, 2nd Floor, Prege Chamber , Travel Agency 2/3/2016 2/2/2021 Mohan Singh Consulbouds opp. Nanrinder Cinema Jalandhar 6 6/MC1/MA Sh. -

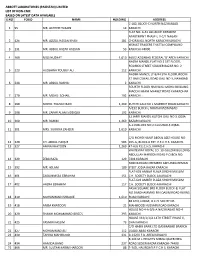

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

The Khilafat Movement in India 1919-1924

THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR T AAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 62 THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 A. C. NIEMEIJER THE HAGUE - MAR TINUS NIJHOFF 1972 I.S.B.N.90.247.1334.X PREFACE The first incentive to write this book originated from a post-graduate course in Asian history which the University of Amsterdam organized in 1966. I am happy to acknowledge that the university where I received my training in the period from 1933 to 1940 also provided the stimulus for its final completion. I am greatly indebted to the personal interest taken in my studies by professor Dr. W. F. Wertheim and Dr. J. M. Pluvier. Without their encouragement, their critical observations and their advice the result would certainly have been of less value than it may be now. The same applies to Mrs. Dr. S. C. L. Vreede-de Stuers, who was prevented only by ill-health from playing a more active role in the last phase of preparation of this thesis. I am also grateful to professor Dr. G. F. Pijper who was kind enough to read the second chapter of my book and gave me valuable advice. Beside this personal and scholarly help I am indebted for assistance of a more technical character to the staff of the India Office Library and the India Office Records, and also to the staff of the Public Record Office, who were invariably kind and helpful in guiding a foreigner through the intricacies of their libraries and archives. -

Title: Need to Impress Upon the Government of Pakistan to Restore the Hindu Temple Demolished in Karachi and Provide Adequate Security to the Minority Hindu Community

> Title: Need to impress upon the Government of Pakistan to restore the Hindu Temple demolished in Karachi and provide adequate security to the minority Hindu community. SHRI BHARTRUHARI MAHTAB (CUTTACK): Chairman, Sir, before I express the issue which I had given, I would like to draw your attention that during Matters of Urgent Importance, notices are considered which are international in nature, national importance, then of State interest, and then of constituency interest. But I am sorry to mention here, I want to be on record, I think, the hon. Speaker, will go through this issue and hon. Parliamentary Affairs Minister also will look into this issue that today, a number of constituency issues were taken up. MR. CHAIRMAN : You just raise your matter. I will look into it. Whatever you want, you tell, it is left to the Chair to decide whether to allow or not. SHRI BHARTRUHARI MAHTAB : This is of national importance and this is of international repercussion. I wanted the House to respond to this. A century old Hindu temple in Karachi was hurriedly demolished by a builder despite a Pakistani Court hearing a petition seeking a stay on such a move. Besides raising the pre-partition Shri Rama Pir Mandir in Karachi's Soldier Bazaar, the builder has also demolished several houses near it last Saturday. Nearly 40 persons, a majority of them Hindus, have become homeless. This has been widely reported in Pakistani media, yet there is no action on behalf of the authorities. The affected families have stated that during demolition the area was cordoned off by the police and paramilitary forces called Pakistani Rangers. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

In the High Court of Sindh at Karachi J U D G M E

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH AT KARACHI PRESENT: Mr. Justice Amjad Ali Sahito Criminal Appeal No.248 of 2020 Criminal Appeal No.287 of 2020 Appellants in Mst. Sehar Shams & Bilal Shams Crl.Appeal 248/2020 : Through Syed Mehmood Alam Rizvi, Advocate. Appellant in Syed Ali-ul-Hassan Crl.Appeal 287/2020 : Through Mr. Zulfiquar Ali Langah, Advocate. Respondent : The State Through Mr. Siraj Ali Khan, Addl. Prosecutor General Sindh. Date of hearing : 3rd September 2020 Date of Judgment : 15th September 2020 J U D G M E N T AMJAD ALI SAHITO, J.– Being aggrieved and dissatisfied with the judgment dated 11.03.2020 passed by learned Vth Additional Sessions Judge/Model Criminal Trial Court (Extension), Karachi East, in Sessions Case No.273 of 2018 arising out of the FIR No.14/2018 for the offence under sections 302, 109, 201, 202/34 PPC registered at Police Station Soldier Bazaar, Karachi, whereby the appellants Ali-ul-Hassan, Sehar Shams and Bilal Shams were convicted under section 302(b) read with section 109/34 PPC and sentenced them to suffer imprisonment for life each as a Taazir and to pay fine of Rs.10,00,000/- as compensation under section 544-A, Cr.P.C. to the legal heirs of deceased Ambreen Fatima. The benefit of section 382 Cr.P.C. was also extended in favour of the appellants and their sentences will run concurrently with other sentences if any. 2. The case of the prosecution as depicted in the FIR lodged by the complainant SIP Sarfaraz Aliyana is that on 09.12.2017, Page 1 of 17 accused Ali-ul-Hassan lodged FIR No.299/2017 under section 302/397 PPC at PS Soldier Bazaar, alleging therein that during street crime his wife Mst. -

Annotated Bibliography of Studies on Muslims in India

Studies on Muslims in India An Annotated Bibliography With Focus on Muslims in Andhra Pradesh (Volume: ) EMPLOYMENT AND RESERVATIONS FOR MUSLIMS By Dr.P.H.MOHAMMAD AND Dr. S. LAXMAN RAO Supervised by Dr.Masood Ali Khan and Dr.Mazher Hussain CONFEDERATION OF VOLUNTARY ASSOCIATIONS (COVA) Hyderabad (A. P.), India 2003 Index Foreword Preface Introduction Employment Status of Muslims: All India Level 1. Mushirul Hasan (2003) In Search of Integration and Identity – Indian Muslims Since Independence. Economic and Political Weekly (Special Number) Volume XXXVIII, Nos. 45, 46 and 47, November, 1988. 2. Saxena, N.C., “Public Employment and Educational Backwardness Among Muslims in India”, Man and Development, December 1983 (Vol. V, No 4). 3. “Employment: Statistics of Muslims under Central Government, 1981,” Muslim India, January, 1986 (Source: Gopal Singh Panel Report on Minorities, Vol. II). 4. “Government of India: Statistics Relating to Senior Officers up to Joint-Secretary Level,” Muslim India, November, 1992. 5. “Muslim Judges of High Courts (As on 01.01.1992),” Muslim India, July 1992. 6. “Government Scheme of Pre-Examination Coaching for Candidates for Various Examination/Courses,” Muslim India, February 1992. 7. National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), Department of Statistics, Government of India, Employment and Unemployment Situation Among Religious Groups in India: 1993-94 (Fifth Quinquennial Survey, NSS 50th Round, July 1993-June 1994), Report No: 438, June 1998. 8. Employment and Unemployment Situation among Religious Groups in India 1999-2000. NSS 55th Round (July 1999-June 2000) Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, September 2001. Employment Status of Muslims in Andhra Pradesh 9. -

Public and Private Control and Contestation of Public Space Amid Violent Conflict in Karachi

Public and private control and contestation of public space amid violent conflict in Karachi Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan Working Paper Urban Keywords: November 2015 Urban development, violence, public space, conflict, Karachi About the authors Published by IIED, November 2015 Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Noman Ahmed: Professor and Chairman, Department of Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan. 2015. Architecture and Planning at NED University of Engineering Public and private control and contestation of public space amid and Technology in Karachi. Email – [email protected] violent conflict in Karachi. IIED Working Paper. IIED, London. Bushra Owais Siddiqui: Young architect in private practice in http://pubs.iied.org/10752IIED Karachi. Email – [email protected] ISBN 978-1-78431-258-9 Dure Shahwar Khalil: Young architect in private practice in Karachi. Email – [email protected] Printed on recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. Sana Tajuddin: Lecturer and Coordinator of Development Studies Programme at NED University, Karachi. Email – sana_ [email protected] Donald Brown: IIED Consultant. Email – donaldrmbrown@gmail. com Gordon McGranahan: Principal Researcher, Human Settlements Group, IIED. Email – [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Human Settlements Group The Human Settlements Group works to reduce poverty and improve health and housing conditions in the urban centres of Africa, Asia -

Vol. 4, No. 2, Pp. 101-118 | ISSN 2050-487X |

Criminal networks and governance: a study of Lyari Karachi Sumrin Kalia Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 101-118 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk 2016 | The South Asianist 4 (2): 101-118 | pg. 101 Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 101-118 Criminal networks and governance: a study of Lyari Karachi SUMRIN KALIA, University of Karachi Karachi, the mega city and the commercial hub of Pakistan has become one of the most dangerous cities of the world in past few decades. This paper uses Lyari, a violent neighbourhood in Karachi, as a case study to find the underlying causes of conflict. The paper builds the argument that political management of crime has created spaces for the criminals to extend their criminal networks. Through connections with state officials and civic leaders, they appropriate state power and social capital that make their ongoing criminal activities possible. I present a genealogical analysis of politico-criminal relationships in Lyari and then examine the interactions of the criminals with the society through qualitative field research. The article also demonstrates how such criminals develop parallel governance systems that transcend state authority, use violence to impose order and work with civic leaders to establish their legitimacy. It is observed that these 'sub-national conflicts' have not only restrained the authority of the government, but have also curtailed accountability mechanisms that rein in political management of crime. The population of Karachi in 1729 was 250, today it is estimated to be more than 20 Million, ranking as the seventh most populous city in the world. From its humble beginnings as a fishing village, the city has grown to become the financial hub of Pakistan. -

Karachi KATRAK BANDSTAND, CLIFTON PHOTO by KHUDABUX ABRO

FEZANA PAIZ 1377 AY 3746 ZRE VOL. 22, NO. 3 FALL/SEPTEMBER 2008 MahJOURJO Mehr-Avan-Adar 1377 (Fasli) G Mah Ardebehest-Khordad-Tir 1378 AY (Shenshai)N G Mah Khordad-Tir-AmardadAL 1378 AY (Kadmi) “Apru” Karachi KATRAK BANDSTAND, CLIFTON PHOTO BY KHUDABUX ABRO Also Inside: 2008 FEZANA AGM in Westminster, CA NextGenNow 2008 Conference 10th Anniversary Celebrations in Houston A Tribute to Gen. Sam Manekshaw PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 22 No 3 Fall 2008, PAIZ 1377 AY 3746 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistan: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 3 Message from the President [email protected] 5 FEZANA Update Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info 6 Financial Report Cover design: Feroza Fitch, [email protected] 35 APRU KARACHI 50 Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff:: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : 56 Renovations of Community Places of [email protected] Fereshteh Khatibi:: [email protected] Worship-Andheri Patel Agiary Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] 78 In The News Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Nikan Khatibi: [email protected] 92 Interfaith /Interalia Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla 99 North American Mobeds’ Council Subscription Managers: Kershaw Khumbatta : 106 Youthfully