Vol. 4, No. 2, Pp. 101-118 | ISSN 2050-487X |

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policing Urban Violence in Pakistan

Policing Urban Violence in Pakistan Asia Report N°255 | 23 January 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Peshawar: The Militant Gateway ..................................................................................... 3 A. Demographics, Geography and Security ................................................................... 3 B. Post-9/11 KPK ............................................................................................................ 5 C. The Taliban and Peshawar ......................................................................................... 6 D. The Sectarian Dimension ........................................................................................... 9 E. Peshawar’s No-Man’s Land ....................................................................................... 11 F. KPK’s Policy Response ............................................................................................... 12 III. Quetta: A Dangerous Junction ........................................................................................ -

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

Responding to the Transport Crisis in Karachi Appendices

Responding to the transport crisis in Karachi Appendices The Urban Resource Centre, Karachi with Arif Hasan and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban Keywords: July 2015 Urban development, urban planning, transport About the authors Produced by IIED’s Human Settlements The Urban Resource Centre, Karachi is a Karachi-based Group NGO founded by teachers, professionals, students, activists The Human Settlements Group works to reduce poverty and and community organizations from low income settlements. improve health and housing conditions in the urban centres of It was set up in response to the recognition that the planning Africa, Asia and Latin America. It seeks to combine this with process for Karachi did not serve the interests of low- and promoting good governance and more ecologically sustainable lower-middle-income groups, small businesses and informal patterns of urban development and rural-urban linkages. sector operators and was also creating adverse environmental and socioeconomic impacts. The Urban Resource Centre has sought to change this through creating an information Acknowledgements base about Karachi’s development on which everyone can draw; also through research and analysis of government This study was initiated, designed and supervised by Arif plans (and their implications for Karachi’s citizens), advocacy, Hasan. The interviews with government officials, transporters, mobilization of communities, and drawing key government staff and community members in the low income settlements, into discussions. This has created a network of professionals were carried out by Zahid Farooq and Rizwan-ul-Haq (Social and activists from civil society and government agencies Organiser and Manager of Documentation respectively of URC, who understand planning issues from the perspective of Karachi). -

PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST July 2020

July 2020 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST July 2020 A Select Summary of News, Views and Trends from the Pakistani Media Prepared by Dr. Zainab Akhter Dr. Nazir Ahmad Mir Dr. Mohammad Eisa Dr. Ashok Behuria MANOHAR PARRIKAR INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES 1-Development Enclave, Near USI Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST, July 2020 CONTENTS POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................... 06 ECONOMIC ISSSUES............................................................................................ 08 SECURITY SITUATION ........................................................................................ 11 PROVINCES ®IONS Balochistan ................................................................................................................. 13 GB ................................................................................................................................ 15 URDU & ELECTRONIC MEDIA Urdu ............................................................................................................................ 20 Electronic .................................................................................................................... 27 STATISTICS BOMBINGS, SHOOTINGS AND DISAPPEARANCES ...................................... 29 MP-IDSA, New Delhi 1 POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS Dangerous delusions, Zahid Hussain, Dawn, 01 July1 Speaking at a dinner for coalition lawmakers recently, the prime minister had boasted: “we are the only choice”. Maybe -

In This Issue 9Th Advisory Board Meeting of NIOC Pakistan Held on July 10, 2020

Newsletter Vol: 09 July 2020 In This Issue 9th advisory board meeting of NIOC Pakistan held on July 10, 2020 ?Minutes of the NIOC 9th Advisory board meeting ?Italian police seize over $1 billion of 'ISIS-made' Captagon amphetamines ?Human Rights, Rule of Law and the Renewed Social Contract in the COVID-19 reality. ?Cabinet to amend law to comply with FATF demand ?Politics of JITs ?Only 14 cyber crime convictions in five years ?An Expert Explains: Why it is necessary to watch the emergence of ISIS in the region ?Regional militant sanctuaries ?Govt gets two FATF- related bills passed through NA amid opposition protest PAKISTAN Peace Studies (PIPS) www.nioc.pk niocpk niocpk niocpk Tariq Parvez President Advisory Board, NIOC: Former Director General Federal Investigation Agency Zahid Hussain Member NIOC AB: Eminent journalist particularly specializing in countering terrorism Samina Ahmed Member NIOC AB: Senior Adviser Asia and Project Director, South Asia for the International Crisis Group Zubair Habib Chairman CPLC Karachi, Member NIOC AB: For community outreach. Jawaid Akhtar QPM Member NIOC AB: Police Officer. retired as the Deputy Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police Fasi Zaka Member NIOC AB: Communications expert. To steer the ADVISORY BOARD advocacy campaign. Tariq Khosa Director Muhammad Amir Rana Secretary Muhammad Ali Nekokara Deputy Director Hassan Sardar NIOC DIRECTORATE Admin & Finance Manager Ammar Hussain Jaffri Communication Strategist Kashif Akram Noon CONSULTANTS Lead Researcher 2 NIOC’s 9th Advisory Board Meeting HE ninth meeting of the National Initiative against Organized Crime (NIOC) Advisory Board (AB) was held on Friday, July 10, 2020 at 5 pm through Zoom video conferencing link. -

Law and Order URC

Law and Order URC NEWSCLIPPINGS JANUARY TO JUNE 2019 LAW & ORDERS Urban Resource Centre A-2, 2nd floor, Westland Trade Centre, Block 7&8, C-5, Shaheed-e-Millat Road, Karachi. Tel: 021-4559317, Fax: 021-4387692, Email: [email protected], Website: www.urckarachi.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/URCKHI Twitter: https://twitter.com/urc_karachi 1 Law and Order URC Targeted killing: KMC employee shot dead in Hussainabad Unidentified assailants shot and killed an employee of the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC) at Hussainabad locality of Federal B Area in Central district on Monday. The deceased was struck by seven bullets in different parts of the body. Nine bullet shells of a 9mm pistol were recovered from the scene of the crime. According to police, the deceased was called to the location through a phone call. They said the late KMC employee was on his motorcycle waiting for someone. Two unidentified men killed him by opening fire at him at Hussainabad, near Okhai Memon Masjid, in the limits of Azizabad police station. The deceased, identified as Shakeel Ahmed, aged 35, son of Shafiq Ahmed, was shifted to Abbasi Shaheed Hospital for medico-legal formalities. He was a resident of house no. L-72 Sector 5C 4, North Karachi, and worked as a clerk in KMC‘s engineering department. Rangers and police officials reached the scene after receiving information of the incident. They recovered nine bullet shells of a 9mm pistol and have begun investigating the incident. According to Azizabad DSP Shaukat Raza, someone had phoned and summoned the deceased to Hussainabad, near Okhai Memon Masjid. -

List of Unclaimed / Unpaid Dividend As of June 30, 2019

Page 1 of 38 SANGHAR SUGAR MILLS LIMITED CONSOLIDATED LIST OF UNCLAIMED / UNPAID DIVIDEND (As at June 30, 2019) DUE DATE FOR TRANSFER INTO THE INVESTOR EDUCATION & PROTECTION FUND: For the year from 1989 to 2010 - Due date of transfer was April 02, 2018 (1st Notice of 90 days sent on October 04, 2017 - Final Notice of 90 days published on January 02, 2018). For the year 2015 - (1st Notice of 90 days sent on June 24, 2019 - Final Notice of 90 days will be published on September 22, 2019). NET UNCLAIMED S. No. FOLIO Year NAME OF SHAREHOLDER ADDRESS NATURE OF AMOUNT DIVIDEND 1 421 1989 Mr. Nagar Khan C/o National Bank of Pakistan , Khipro,Teshil Khipro,District Sanghar UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 1,550 2 495 1989 Mr. Amin M. Rajar C/o Haji Khan Mohd Mangrio,Dhoronard,Disttrict Tharparkar. UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 310 3 526 1989 Mr. Ghardari Lal Kapro Khipro,District Sanghar UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 620 4 530 1989 Mr. Gobind Ram Kapro Khipro,District Sanghar UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 620 5 974 1989 Mrs. Zubaida UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 465 6 1004 1989 Mr. Muhammad Riaz 5-E-22/29, Paposhnagar, Karachi UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 620 7 1841 1989 Mr. Muzahir Ali G K 4/4, Sadruddin Building, R. No. 5, Kassam Street, Kharadar, Karachi UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 310 8 2010 1989 Mst. Shahista UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 620 9 2083 1989 Mr. Muhammad Anwar Kayani UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 155 10 2103 1989 Mr. Amin Flat No. 3, 2nd Floor, JT 1/1, Haji Nauroze Building, Nawab Mohabbat Khanji Road, Kharadar, Karachi UN CLAIMED DIVIDEND 775 11 2181 1989 Mst. -

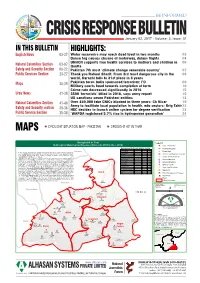

Crisis Response Bulletin V3I1.Pdf

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN January 02, 2017 - Volume: 3, Issue: 01 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 03-27 Water reservoirs may reach dead level in two months 03 Dense fog causes closure of motorway, delays flights 04 UNHCR supports free health services to mothers and children in 06 Natural Calamities Section 03-07 Quetta Safety and Security Section 08-22 Pakistan 7th most ‘climate change venerable country’ 07 Public Services Section 23-27 Thank you Raheel Sharif: From 3rd most dangerous city in the 08 world, Karachi falls to 31st place in 3 years Maps 28-29 Pakistan faces India sponsored terrorism: FO 09 Military courts head towards completion of term 10 Crime rate decreased significantly in 2016 15 Urdu News 41-30 3500 ‘terrorists’ killed in 2016, says army report 15 US sanctions seven Pakistani entities 18 Natural Calamities Section 41-40 Over 450,000 fake CNICs blocked in three years: Ch Nisar 19 Army to facilitate local population in health, edu sectors: Brig Tahir23 Safety and Security section 39-36 HEC decides to launch online system for degree verification 23 Public Service Section 35-30 ‘WAPDA registered 5.7% rise in hydropower generation’ 24 MAPS DROUGHT SITUATION MAP - PAKISTAN DROUGHT HIT IN THAR Drought Hit in Thar Legend Outbreak of Waterborne Diseases (from Jan,2016 to Dec, 2016) G Basic Health Unit Government & Private Health Facility ÷Ó Children Hospital Health Facility Government Private Total Sanghar Basic Health Unit 21 0 21 G Dispensary At least nine more infants died due to malnutrition and outbreak of the various diseases in Thar during that last two Children Hospital 0 1 1 days, raising the toll to 476 this year.With the death of nine more children the toll rose to 476 during past 12 months Dispensary 12 0 12 "' District Headquarter Hospital of the outgoing year, said health officials. -

Informal Land Controls, a Case of Karachi-Pakistan

Informal Land Controls, A Case of Karachi-Pakistan. This Thesis is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Saeed Ud Din Ahmed School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University June 2016 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i | P a g e STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………………………………………..………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …………………………………………………………….…………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed …………………………………………………….……………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii | P a g e iii | P a g e Acknowledgement The fruition of this thesis, theoretically a solitary contribution, is indebted to many individuals and institutions for their kind contributions, guidance and support. NED University of Engineering and Technology, my alma mater and employer, for financing this study. -

Political Turmoil in a Megacity: the Role of Karachi for the Stability of Pakistan and South Asia

Political Turmoil in a Megacity: The Role of Karachi for the Stability of Pakistan and South Asia Bettina Robotka Political parties are a major part of representative democracy which is the main political system worldwide today. In a society where direct modes of democracy are not manageable any more – and that is the majority of modern democracies- political parties are a means of uniting and organizing people who share certain ideas about how society should progress. In South Asia where democracy as a political system was introduced from outside during colonial rule only few political ideologies have developed. Instead, we find political parties here are mostly based on ethnicity. The flowing article will analyze the Muttahida Qaumi Movement and the role it plays in Karachi. Karachi is the largest city, the main seaport and the economic centre of Pakistan, as well as the capital of the province of Sindh. It is situated in the South of Pakistan on the shore of the Arabian Sea and holds the two main sea ports of Pakistan Port Karachi and Port Bin Qasim. This makes it the commercial hub of and gateway to Pakistan. The city handles 95% of Pakistan’s foreign trade, contributes 30% to Pakistan’s manufacturing sector, and almost 90% of the head offices of the banks, financial institutions and 2 Pakistan Vision Vol. 14 No.2 multinational companies operate from Karachi. The country’s largest stock exchange is Karachi-based, making it the financial and commercial center of the country as well. Karachi contributes 20% of the national GDP, adds 45% of the national value added, retains 40% of the national employment in large-scale manufacturing, holds 50% of bank deposits and contributes 25% of national revenues and 40% of provincial revenues.1 Its population which is estimated between 18 and 21million people makes it a major resource for the educated and uneducated labor market in the country. -

Live Trees and Other Plants (Hs 06)

EXPORTERS OF PAKISTAN SECTOR - LIVE TREES AND OTHER PLANTS (HS 06) S. Exporters Name NTN Exporters Address No. A&Z ENTERPRISES(IMPORTER AND 1 4263869 119-F, JOHAR TOWN LAHORE EXPORTER) 2 A.S ENTERPRISES 3425233 8,K M,RAIWIND,ROAD,LAHORE,PUNAJAB 3 AFTAB TRADERS 4385127 OFFICE NO.29/A,DAR MAIZA 9TH FLOOR, DAWOOD 4 AHMAD ITTEHAD ENTERPRISES 4163688 ATIF CENTER,JAIN MANDER STOP,LHO 5 AHSAN ENTERPRISES 7373171 OFFICE NO3 ASIF BULIDING MULTAN ROAD LAHORE 6 AL ABBAS TRADERS 7579462 7 AL WAHHAB FOOD INDUSTRIES 1439720 603-B SATELLITE TOWN, GUJRANWALA. 8 AL WALEED INTL 1044643 D 42 BLOCK 4 GULSHAN E IQBAL ,KARACHI 9 AL ZAIN INTERNATIONAL TRADERS 4039636 902-BLOCK-B SABZAZAR SCHEME MULTAN ROAD 10 AL-HUDA ENTERPRISES (PVT.) LIMITED 7108983 11 AL-MAJID GARMENTS 275337 OT 3/164 KARAR SHAH LANE MITHADAR, KARACHI 12 AL-MARYAM INTERNATIONAL 1002632 A-1284 MARKET ROAD,HYDERABAD OFFICE NO. A-5 GULBERG BLOCK-12 FEDERAL B AREA 13 AL-MUBARAK IMPEX 4206199 KARACHI 810-E, 8TH FLOOR, NAZ PLAZA, M.A.JINNAH ROAD, 14 ANA INTERNATIONAL 3415702 ,KARACHI H#5/371,SHAH FAISAL 15 ARMAAN INTERNATIONAL 2288901 TOWN,KARACHI,KARACHI,SINDH P-118 IST FLOOR STREET NO 03 GULISTRAN MARKET 16 ARROW INTERNATIONAL 7392206 RAILWAY ROAD FAISALABAD HOUSE NO 2 JINNAH PARK COLLEGE ROAD 17 ASAS ENTERPRISES 2219339 SARGODHA 111, GULSHN-E- IQBAL COLONY, QABOOLA ROAD ARIF 18 BAGHBAN NUERSERY FARM 4052841 WALA ARIFWALA PAKPATTAN. 19 BILAL NADEEM ENTERPRISES 2947699 62-A, BLOCK-6 P.E.C.H.S,KARACHI 20 BINT AL ARAB ENTERPRISES 3667408 273 STREET NO.1,FANCY PARK WALTON ROAD 2ND FLOOR RIMO CHOWK -

ORANGI PILOT PROJECT Institutions and Programs

822 PKOR03 ORANGI PILOT PROJECT Institutions and Programs 93rd QUARTERLY REPORT JAN,FEB, MAR'2003 Replication by LPP in Khanpur City is an important initiative. Laying of Trunk Sewer is in Progress. PLO1 NO. ST-4, SECTOR S/A, QASBA COLONY MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI-75800 PHONE NOS. 6658021-6652297 Fax: 6665696, E-mail : [email protected] pk & [email protected] ORANGI PILOT PROJECT - Institutions and Programs Contents: Pages I. Introduction: 1-2 II. Receipts and Expenditure-Audited figure (1980 to 2002) 3 (OPP and OPP society) III. Receipts and Expenditure (2002-2003) Abstract of institutions 4 IV. Orangi Pilot Project - Research and Training Institute (OPP-RTI) 5-61 V. OPP-KHASDA Health and Family Planning Programme (KHASDA) 62-74 VI. Orangi Charitable Trust: Micro Enterprise Credit (OCT) 75-106 VII. Rural Development Trust (RDT) 107-114 I. INTRODUCTION: 1. Since April 1980 the following programs have evolved: Low Cost Sanitation-started in 1981 Low Cost Housing-started in 1986 Health & Family Planning-started in 1985 Women Entrepreneurs- started in 1984, later merged with Family Enterprise • Family Enterprise-started in 1987 Education- started in 1987 stopped in 1990. New program started in 1995. Social Forestry-started in 1990 stopped in 1997 Rural Development- started in 1992 2. The programs are autonomous with their own registered institutions, separate budgets, accounts and audits. The following independent institutions are now operating : i. OPP Society Council: It receives funds from INFAQ Foundation and distributes the funds according to the budgets to the Women Section (OCT), OPP-RTI, Khasda and RDT . For details of distribution see page 4.