THE SONG WAS THERE BEFORE ME: the Influence Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Come See a Joyful Noise in Concert At

Folk Music Society of NY Inc./NY Pinewoods Folk Music Club and The Renaissance Charter School present New York, New York Music Traditions & People Celebrating Oscar Brand &the 65th year of his Radio Show on WNYC Saturday, March 13, 2010 American, English, Asian & Latin American Folk Music 11:00 AM - free family concert: 12:30 -5:30 PM – workshops, mini-concerts, & open mike 7:30 PM Concert at The Renaissance Charter School 35-59 81st Street (NE corner of 37th Avenue) Jackson Heights, Queens, New York (Subway to 82 Street Station of #7 line) Parking available one block away. $15 Whole Day, $10 Afternoon Workshops or Evening Concert $5 Children 13-18 all day or part; Children 12 & under free when accompanied by adult. TRCS students and staff free Tickets are available at the door or online at www.brownpapertickets/event/98896 Information: www.folkmusicny.org or 718-672-6399 Special thanks to Assembly Member Jose Peralta for assistance in making this possible. 3/9/10 New York, New York; Music Traditions & People • Norris Bennett is the lead singer of the Ebony Hillbillies, plays Southern Mountain and country songs from an African-American perspective, accompanied on guitar, banjo, and dulcimer. • The Bobby Kyle Band plays and sings acoustic blues. (Bobby Kyle, Marc Copell and Everett Boyd, bass player and music instructor at TRCS). • Oscar Brand is a great performer as well being in the Guiness Book of World Records as the host of the longest- running continuous single hosted show in history, Saturday nights, 10 pm on WNYC, 820 AM, NYC. -

Bob Dylan and the Nobel Prize

BOB ENNOBLED BOB DYLAN AND THE NOBEL PRIZE I am a Dylan fan and I know many of his songs by heart. I have seen him perform and have heard him mangle his own work in Birmingham, England, and then delight the Hammersmith Odeon. I have watched him forget some of the words to ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ in the Leisure Centre at Bournemouth. Indeed, since about 1963 and The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan I have spent many leisure hours and vital pounds, first of pocket money and then of earned income, keeping up with much of Dylan’s copious output. I’ve even tried to read his ‘novel’ Tarantula. While I am aware of his vocal and musical limitations and the way he can move from brilliant to dire, I love some of his songs, his phrasing and intonation this side of idolatry and sometimes beyond. I think the first four Dylan tracks I bought were on an 1963 EP called Dylan (Extended Play: remember those?) which rotated on the turntable at 45 rpm as his astonishing twenty-one-year old-voice sang: ‘Don’t Think Twice, it’s alright’, ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, ‘When the Ship Comes in’ and then was it ‘Corinna, Corinna’? His way with song words has long held my qualified admiration and I enjoyed reading his Chronicles (Volume One) when they came out in 2004. For me, even with Dylan at his uneven best, it’s the words that matter most and the way he delivers them in the best of his supremely memorable songs. If I had to name my current top ten of his tracks, chosen with particular attention to the words and to do so rapidly from memory, I’d probably go for the following: ‘Boots -

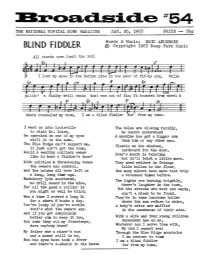

BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic

c:l.si THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE JAN. 20, 1965 PRICE -- 50¢ Words & Music: ERIC ANDERSEN BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic All chords open (omit the 3rd) there concealed my doom, I am a blind fiddler . ar from my home. I went up into Louisville The holes are closing rapidly, to visit Dr. Laine, he cannot understand He operated on one of my eyes A machine has got a bigger arm still it is the same. than him or ~ other man. The Blue Ridge can't support me, Plastic on the ,windows, it just ain't got the room, cardboard for the door, Would a wealthy colliery owner Baby's mouth is twisting like to hear a fiddler's tune? but it'll twist a little more. With politics & threatening tones They need welders in Chicago the owners can control, falls hollow to the floor, And the unions all have left us How many miners have made that trip a long, long time ago. a thousand times before. Machinery ~in scattered, The lights are burning brightly, nCOJ drill sound in the mine, there's laughter in the town, For all the good a collier is But the streets are dark and empty, you might as well be blind. ain I t a miner to be found. Was a time I worked a long 14 They're in some lonesome holler for a short 8 bucks a day. where the sun refuse to shine, You I re lucky if you're workin A baby's cries are muffled that's what the owners say. -

Theo Bikel with Pete Seeger (And More)

Theo Bikel with Pete Seeger (and more) First, here’s another item for consideration by people who think that Pete Seeger was anti-Israel. (If you haven’t already, read Hillel Schenker’s recent post on this.) We have the permission of Gerry Magnes — active with the Albany, NY regional J Street chapter, who married into an Israeli family — to quote what he emailed the other day: Thought I would share a small anecdote my father in law once told me. He’s 95 and still living on a kibbutz (Kibbutz Evron) in the Western Galilee. Last winter, when my wife and I mentioned to him that we’d just attended a Pete Seeger concert . in Schenectady, . he related how he’d seen him perform (I think in Tel Aviv), probably in ’64. When he [Seeger] began to speak about the Israeli-Palestinian/Arab conflict at that time and his hopes for peace, he began to cry. He had to stop talking or singing for a bit until he could collect himself. The sincerity and depth of feeling left a deep impression on my father in law. http://www.cookephoto.com/dylanovercome.html Partners’ board chair Theodore Bikel goes back a long way with Seeger. They were part of the original board (with Oscar Brand, George Wein and Albert Grossman) that founded the Newport Folk Festival. This image captures a festival high point in 1963, with Theo and Seeger (at right) joining Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, the Freedom Singers and Peter, Paul and Mary to sing “We Shall Overcome.” Here’s Theo singing Hine Ma Tov with Seeger and Rashid Hussain (the latter identified as a Palestinian poet) from episode 29 of the 39-episode run of the “Rainbow Quest” UHF television series (1965-66), dedicated to folk music and hosted by Seeger: Upon hearing of Seeger’s passing, Theo wrote this on his Facebook page: An era has come to an end. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

Still on the Road 1990 Us Fall Tour

STILL ON THE ROAD 1990 US FALL TOUR OCTOBER 11 Brookville, New York Tilles Center, C.W. Post College 12 Springfield, Massachusetts Paramount Performing Arts Center 13 West Point, New York Eisenhower Hall Theater 15 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 16 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 17 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 18 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 19 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 21 Richmond, Virginia Richmond Mosque 22 Pittsburg, Pennsylvania Syria Mosque 23 Charleston, West Virginia Municipal Auditorium 25 Oxford, Mississippi Ted Smith Coliseum, University of Mississippi 26 Tuscaloosa, Alabama Coleman Coliseum 27 Nashville, Tennessee Memorial Hall, Vanderbilt University 28 Athens, Georgia Coliseum, University of Georgia 30 Boone, North Carolina Appalachian State College, Varsity Gymnasium 31 Charlotte, North Carolina Ovens Auditorium NOVEMBER 2 Lexington, Kentucky Memorial Coliseum 3 Carbondale, Illinois SIU Arena 4 St. Louis, Missouri Fox Theater 6 DeKalb, Illinois Chick Evans Fieldhouse, University of Northern Illinois 8 Iowa City, Iowa Carver-Hawkeye Auditorium 9 Chicago, Illinois Fox Theater 10 Milwaukee, Wisconsin Riverside Theater 12 East Lansing, Michigan Wharton Center, University of Michigan 13 Dayton, Ohio University of Dayton Arena 14 Normal, Illinois Brayden Auditorium 16 Columbus, Ohio Palace Theater 17 Cleveland, Ohio Music Hall 18 Detroit, Michigan The Fox Theater Bob Dylan 1990: US Fall Tour 11530 Rose And Gilbert Tilles Performing Arts Center C.W. Post College, Long Island University Brookville, New York 11 October 1990 1. Marines' Hymn (Jacques Offenbach) 2. Masters Of War 3. Tomorrow Is A Long Time 4. -

Bound for Glory Bob Dylan 1962

BOUND FOR GLORY BOB DYLAN 1962 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, RELEASES, TAPES & BOOKS. © 2001 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Bound For Glory — Bob Dylan 1962 page 2 CONTENTS: 1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................... 3 2 YEAR AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................. 3 3 CALENDAR .............................................................................................................................. 3 4 RECORDINGS ......................................................................................................................... 7 5 SONGS 1962 .............................................................................................................................. 7 6 SOURCES .................................................................................................................................. 9 7 SUGGESTED READINGS .................................................................................................... 10 7.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND .................................................................................................... 10 7.2 ARTICLE COMPILATIONS ................................................................................................... -

Hollis Brown :: 3 Shots Blue Rose/Sonic Rendezvous

Hollis Brown :: 3 Shots Blue Rose/Sonic RendezVous Since New York-based band Hollis Brown started out in 2009, they have grown into one of the most convincing current young rock’n’roll acts. While their music is based on an almost inexhaustible pool of 60ies and 70ies influences yet anchored in the here and now, their releases show a clear development from the raw, direct sound of their debut to the complex, multi-faceted approach on their new album 3 Shots. The album’s eleven songs document Hollis Brown’s grown creativity, more substantial songwriting and a more clearly-defined identity. 3 Shots is their fourth full-length album, the first to be released in Europe on Blue Rose Records. Named after an early Bob Dylan song (The Ballad Of Hollis Brown), school friends Mike Montali and Jon Bonilla founded this band as a quartet in 2009 in Queens, NY. Their eponymous debut and a few privately released EPs indicate great passion and drive as well as a search for musical direction. With the widely distributed 2013 album Ride On The Train Hollis Brown started a-rolling – with very fresh- sounding first-class American rock’n’roll. Combining 60ies and 70ies virtues with No Depression and alt.Americana sounds, the foursome convey a deep appreciation and knowledge of Creedence Clearwater Revival, Neil Young, The Band, Tom Petty, Rolling Stones and The Kinks. Produced by the experienced Adam Landry (Allison Moorer, Deer Tick) Hollis Brown are entering a garage-y, blues- and southern rock-drenched terrain with an indie-rock-meets-alt.country-vibe not unlike Marah, Middle Brother, Felice Brothers, Delta Spirit, even Whiskeytown or Green On Red. -

Still on the Road Session Pages: 1961

STILL ON THE ROAD 1961 FEBRUARY OR MARCH East Orange, New Jersey The Home of Bob and Sid Gleason, “The East Orange Tape” MAY 6 Branford, Connecticut Montewese Hotel, Indian Neck Folk Festival Minneapolis, Minnesota Unidentified coffeehouse, “Minnesota Party Tape 1961” JULY 29 New York City, New York Riverside Church, Hootenanny Special SEPTEMBER 6 New York City, New York Gaslight Café, “The First Gaslight Tape” Late New York City, New York Gerde's Folk City 30 New York City, New York Columbia Recording Studios, Carolyn Hester studio session OCTOBER 29 New York City, New York WNYC Radio Studio Late New York City, New York Folklore Center NOVEMBER 4 New York City, New York Carnegie Chapter Hall 20, 22 New York City, New York Studio A, Columbia Recordings, Bob Dylan recording sessions Late New York City, New York Unidentified Location, Interview conducted by Billy James 23 New York City, New York The Home Of Eve and Mac McKenzie DECEMBER 4 New York City, New York The Home Of Eve and Mac McKenzie 22 Minneapolis, Minnesota The Home Of Bonnie Beecher, Minnesota Hotel Tape Bob Dylan sessions 1961 20 The Home of Bob and Sid Gleason East Orange, New Jersey February or March 1961 1. San Francisco Bay Blues (Jesse Fuller) 2. Jesus Met The Woman At The Well (trad.) 3. Gypsy Davey (trad., arr Woody Guthrie) 4. Pastures Of Plenty (Woody Guthrie) 5. Trail Of The Buffalo (trad., arr Woody Guthrie) 6. Jesse James (trad.) 7. Car, Car (Woody Guthrie) 8. Southern Cannonball (R. Hall/Jimmie Rodgers) 9. Bring Me Back, My Blue-Eyed Boy (trad.) 10. -

ARSC Journal, Vol

NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO ARTS AND PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS By Frederica Kushner Definition and Scope For those who may be more familiar with commercial than with non-commercial radio and television, it may help to know that National Public Radio (NPR) is a non commercial radio network funded in major part through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and through its member stations. NPR is not the direct recipient of government funds. Its staff are not government employees. NPR produces programming of its own and also uses programming supplied by member stations; by other non commercial networks outside the U.S., such as the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC); by independent producers, and occasionally by commercial networks. The NPR offices and studios are located on M Street in Washington, D.C. Programming is distributed via satellite. The radio programs included in the following listing are "arts and performance." These programs were produced or distributed by the Arts Programming Department of NPR. The majority of the other programming produced by NPR comes from the News and Information Department. The names of the departments may change from time to time, but there always has been a dichotomy between news and arts programs. This introduction is not the proper place for a detailed history of National Public Radio, thus further explanation of the structure of the network can be dispensed with here. What does interest us are the varied types of programming under the arts and performance umbrella. They include jazz festivals recorded live, orchestra concerts from Europe as well as the U.S., drama of all sorts, folk music concerts, bluegrass, chamber music, radio game shows, interviews with authors and composers, choral music, programs illustrating the history of jazz, of popular music, of gospel music, and much, much more. -

May 1965 Sing Out, Songs from Berkeley, Irwin Silber

IN THIS ISSUE SONGS INSTRUMENTAL TECHNIQUES OF AMERICAN FOLK GUITAR - An instruction book on Carter Plcldng' and Fingerplcking; including examples from Elizabeth Cotten, There But for Fortune 5 Mississippi John Hurt, Rev. Gary Davis, Dave Van Ronk, Hick's Farewell 14 etc, Forty solos fUll y written out in musIc and tablature. Little Sally Racket 15 $2.95 plus 25~ handllng. Traditional stringed Instruments, Long Black Veil 16 P.O. Box 1106, Laguna Beach, CaUl. THE FOLK SONG MAGAZINE Man with the Microphone 21 SEND FOR YOUR FREE CATALOG on Epic hand crafted 'The Verdant Braes of Skreen 22 ~:~~~d~e Epic Company, 5658 S. Foz Circle, Littleton, VOL. 15, NO. 2 W ith International Section MAY 1965 75~ The Commonwealth of Toil 26 -An I Want Is Union 27 FREE BEAUTIFUL SONG. All music-lovers send names, Links on the Chain 32 ~~g~ ~ses . Nordyke, 6000-21 Sunset, Hollywood, call!. JOHNNY CASH MUDDY WATERS Get Up and Go 34 Long Thumb 35 DffiE CTORY OF COFFEE HOUSE S Across the Country ••• The Hell-Bound Train 38 updated edition covers 150 coffeehouses: addresses, des criptions, detaUs on entertaInment policies. $1 .00. TaUs Beans in My Ears 45 man Press, Boz 469, Armonk, N. Y. (Year's subscription Cannily, Cannily 46 to supplements $1.00 additional). ARTICLES FOLK MUSIC SUPPLIE S: Records , books, guitars, banjos, accessories; all available by mall. Write tor information. Denver Folklore Center, 608 East 17th Ave., Denver 3, News and Notes 2 Colo. R & B (Tony Glover) 6 Son~s from Berkeley NAKADE GUITARS - ClaSSical, Flamenco, Requinta. -

The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributions and Contradictions Author(S): Jens Lund and R

The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributions and Contradictions Author(s): Jens Lund and R. Serge Denisoff Source: The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 84, No. 334 (Oct. - Dec., 1971), pp. 394-405 Published by: American Folklore Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/539633 . Accessed: 22/09/2011 16:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Folklore Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of American Folklore. http://www.jstor.org JENS LUND and R. SERGE DENISOFF The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributionsand Contradictions' OBSERVERS OF THE SO-CALLED "COUNTER CULTURE" have tended to portray this phenomenonas a new and isolated event. TheodoreRoszak, as well as nu- merousmusic and art historians,have cometo view the "counterculture" as a new reactionto technicalexpertise and the embourgeoismentof growing segmentsof the Americanpeople.2 This position,it would appear,is basicallyindicative of the intellectual"blind men and the elephant"couplet, where a social fact or event is examinedapart from otherstructural phenomena. Instead, it is our contentionthat the "counterculture" or Abbie Hoffman's"Woodstock Nation" is an emergent realityor a productof all that camebefore, sui generis.More simply,the "counter culture"can best be conceptualizedas partof a long historical-intellectualprogres- sion beginningwith the "Gardenof Eden"image of man.