The Model Prisoner Reading Confinement in Alias Grace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood Adapted for the Stage by Jennifer Blackmer Directed by RTE Co-Founder Karen Kessler

Contact: Cathy Taylor / Kelsey Moorhouse Cathy Taylor Public Relations, Inc. For Immediate Release [email protected] June 28, 2017 773-564-9564 Rivendell Theatre Ensemble in association with Brian Nitzkin announces cast for the World Premiere of Alias Grace By Margaret Atwood Adapted for the Stage by Jennifer Blackmer Directed by RTE Co-Founder Karen Kessler Cast features RTE members Ashley Neal and Jane Baxter Miller with Steve Haggard, Maura Kidwell, Ayssette Muñoz, David Raymond, Amro Salama and Drew Vidal September 1 – October 14, 2017 Chicago, IL—Rivendell Theatre Ensemble (RTE), Chicago’s only Equity theatre dedicated to producing new work with women at the core, in association with Brian Nitzkin, announces casting for the world premiere of Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood, adapted for the stage by Jennifer Blackmer, and directed by RTE Co-Founder Karen Kessler. Alias Grace runs September 1 – October 14, 2017, at Rivendell Theatre Ensemble, 5779 N. Ridge Avenue in Chicago. The press opening is Wednesday, September 13 at 7:00pm. This production of Alias Grace replaces the previously announced Cal in Camo, which will now be presented in January 2018. The cast includes RTE members Ashley Neal (Grace Marks) and Jane Baxter Miller (Mrs. Humphrey), with Steve Haggard (Simon Jordan), Maura Kidwell (Nancy Montgomery), Ayssette Muñoz (Mary Whitney), David Raymond (James McDermott), Amro Salama (Jerimiah /Jerome Dupont) and Drew Vidal (Thomas Kinnear). The designers include RTE member Elvia Moreno (scenic), RTE member Janice Pytel (costumes) and Michael Mahlum (lighting). A world premiere adaptation of Margaret Atwood's acclaimed novel Alias Grace takes a look at one of Canada's most notorious murderers. -

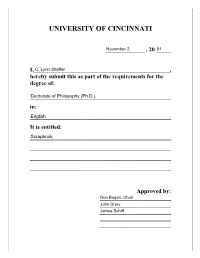

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ SCRAPBOOK A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2001 by C. Lynn Shaffer B.A., Morehead State University, 1993 M.A., Morehead State University, 1995 Committee Chair: Don Bogen C. Lynn Shaffer Dissertation Abstract This dissertation, a collection of original poetry by C. Lynn Shaffer, consists of three sections, predominantly persona poems in narrative free verse form. One section presents the points of view of different individuals; the other sections are sequences that develop two central characters: a veteran living in modern-day America and the historical figure Secondo Pia, a nineteenth-century Italian lawyer and photographer whose name is not as well known as the image he captured -

Annual Atwood Bibliography 2016

Annual Atwood Bibliography 2016 Ashley Thomson and Shoshannah Ganz This year’s bibliography, like its predecessors, is comprehensive but not complete. References that we have uncovered —almost always theses and dissertations —that were not available even through interlibrary loan, have not been included. On the other hand, citations from past years that were missed in earlier bibliographies appear in this one so long as they are accessible. Those who would like to examine earlier bibliographies may now access them full-text, starting in 2007, in Laurentian University’s Institutional Repository in the Library and Archives section . The current bibliography has been embargoed until the next edition is available. Of course, members of the Society may access all available versions of the Bibliography on the Society’s website since all issues of the Margaret Atwood Studies Journal appear there. Users will also note a significant number of links to the full-text of items referenced here and all are active and have been tested on 1 August 2017. That said—and particularly in the case of Atwood’s commentary and opinion pieces —the bibliography also reproduces much (if not all) of what is available on-line, since what is accessible now may not be obtainable in the future. And as in the 2015 Bibliography, there has been a change in editing practice —instead of copying and pasting authors’ abstracts, we have modified some to ensure greater clarity. There are a number of people to thank, starting with Dunja M. Mohr, who sent a citation and an abstract, and with Desmond Maley, librarian at Laurentian University, who assisted in compiling and editing. -

Gender Politics and Social Class in Atwood's Alias Grace Through a Lens of Pronominal Reference

European Scientific Journal December 2018 edition Vol.14, No.35 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Gender Politics and Social Class in Atwood’s Alias Grace Through a Lens of Pronominal Reference Prof. Claudia Monacelli (PhD) Faculty of Interpreting and Translation, UNINT University, Rome, Italy Doi:10.19044/esj.2018.v14n35p150 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n35p150 Abstract In 1843, a 16-year-old Canadian housemaid named Grace Marks was tried for the murder of her employer and his mistress. The jury delivered a guilty verdict and the trial made headlines throughout the world. Nevertheless, opinion remained resolutely divided about Marks in terms of considering her a scorned woman who had taken out her rage on two, innocent victims, or an unwitting victim herself, implicated in a crime she was too young to understand. In 1996 Canadian author Margaret Atwood reconstructs Grace’s story in her novel Alias Grace. Our analysis probes the story of Grace Marks as it appears in the Canadian television miniseries Alias Grace, consisting of 6 episodes, directed by Mary Harron and based on Margaret Atwood’s novel, adapted by Sarah Polley. The series premiered on CBC on 25 September 2017 and also appeared on Netflix on 3 November 2017. We apply a qualitative (corpus-driven) and qualitative (discourse analytical) approach to examine pronominal reference for what it might reveal about the gender politics and social class in the language of the miniseries. Findings reveal pronouns ‘I’, ‘their’, and ‘he’ in episode 5 of the miniseries highly correlate with both the distinction of gender and social class. -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY He'll: Parody in the Canadian Poetic Novel by Nathan Russel Dueck A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA NOVEMBER, 2009 © Nathan Russel Dueck 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-64097-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-64097-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction By Kym Michelle Brindle Thesis submitted in fulfilment for the degree of PhD in English Literature Department of English and Creative Writing Lancaster University September 2010 ProQuest Number: 11003475 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003475 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis examines the significance of a ubiquitous presence of fictional letters and diaries in neo-Victorian fiction. It investigates how intercalated documents fashion pastiche narrative structures to organise conflicting viewpoints invoked in diaries, letters, and other addressed accounts as epistolary forms. This study concentrates on the strategic ways that writers put fragmented and found material traces in order to emphasise such traces of the past as fragmentary, incomplete, and contradictory. Interpolated documents evoke ideas of privacy, confession, secrecy, sincerity, and seduction only to be exploited and subverted as writers idiosyncratically manipulate epistolary devices to support metacritical agendas. Underpinning this thesis is the premise that much literary neo-Victorian fiction is bound in an incestuous relationship with Victorian studies. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47272-2 — the Cambridge History of the Gothic Volume 3: Gothic in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47272-2 — The Cambridge History of the Gothic Volume 3: Gothic in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Index More Information Index Abbott, Stacey, 3, 25–6, 29 Alt-Right movement, 299–301 Abraham, Nicolas, 254 American Horror Story: Cult (television), Absalom, Absalom (Faulkner), 65, 69 299–300 aesthetics, Modernist Gothic and, 44–9, 50 American Psycho (film), 294 African American writers. See also specific Amirpour, Ana Lily, 383, 385 writers The Anatomist (Bridie), 224 Southern Gothic literature and, after Ancuta, Katarzyna, 404–5 World War II, 74–6 And the Band Played On (Shilts), 275–6 Age of Anxiety, 369–70 Andersen, Hans Christian, 37–8, 427 Imperial Gothic and, 370 Andersen, Tryggve, 427 Agee, James, 76 Anderson, Eric, 68 Agrarians, as regional group, 71–2 Andeweg, Agnes, 233 Agrippa, Cornelius, 160 Anger, Kenneth, 215 Ahn Byung-ki, 417–18 Anil’s Ghost (Ondaatje), 356 AIDS narratives, Queer Gothic and, 264–82 Animal’s People (Sinha), 133–4 contagion and, 265–6, 268–9, 278–9 Antichrist (film), 435–6 guilt and innocence and, of affected anti-psychiatry movement, 191 individuals, 265 Anvari, Babak, 383, 385 homophobia influenced by, 265–6 apocalyptic Gothic LGBTQ+ identity and, 265–6 Cold War catastrophe, 470–4 medical timeline of AIDS discovery, 264–5 as end of history, 477–9 medication development, 275, 279–80 future in, optimism about, 480–2 moral judgement of affected rationalism in, 474–7 individuals, 265 re-enchantment in, 474–7 from 1981 to 1991, 266–75 religious history of, 465–6 The Hunger, -

Current Atwood Checklist, 2010 Ashley Thomson and Shannon Hengen

Current Atwood Checklist, 2010 Ashley Thomson and Shannon Hengen This year’s checklist of works by and about Margaret Atwood published in 2010 is, like its predecessors, comprehensive but not complete. In fact, citations from earlier years that were missed in past checklists appear in this one. There are a number of people to thank starting with Desmond Maley, librarian at Laurentian University, and Leila Wallenius, University Librarian. And thanks to Lina Y. Beaulieu, Dorothy Robb and Diane Tessier of the library’s interlibrary loan section. Finally, thanks to the ever-patient Ted Sheckels, editor of this journal. As always, we would appreciate that any corrections to this year’s list or contributions to the 2011 list be sent to [email protected] or [email protected] . Atwood’s Works Alias Grace. Toronto: Emblem/McClelland & Stewart, 2010. ©1999. L’Anno del Diluvio. Milano: Ponte alle Grazie, 2010. Italian translation of The Year of the Flood by Guido Calza. “Atwood in the Sun?: Canadian Author and (Scotch-Swilling) Icon Fires Back at Us Over Sun TV News (and We’re So Scared!).” Toronto Sun 19 September 2010: Section: Editorial/Opinion: 07. In this Letter to the editor, Atwood responds to several charges leveled at her by The Toronto Sun, a right-wing newspaper owned by a company trying to secure a licence for a new right-wing TV station. The charges came after she signed a petition from the US-based group Avaaz charging that “Prime Minister Stephen Harper is trying to push American-style hate media” onto Canadian airwaves. Eventually, 81,000 people signed the petition. -

TV Shows (VOD)

TV Shows (VOD) 11.22.63 12 Monkeys 13 Reasons Why 2 Broke Girls 24 24 Legacy 3% 30 Rock 8 Simple Rules 9-1-1 90210 A Discovery of Witches A Million Little Things A Place To Call Home A Series of Unfortunate Events... APB Absentia Adventure Time Africa Eye to Eye with the Unk... Aftermath (2016) Agatha Christies Poirot Alex, Inc. Alexa and Katie Alias Alias Grace All American (2018) All or Nothing: Manchester Cit... Altered Carbon American Crime American Crime Story American Dad! American Gods American Horror Story American Housewife American Playboy The Hugh Hefn...American Vandal Americas Got Talent Americas Next Top Model Anachnu BaMapa Ananda Ancient Aliens And Then There Were None Angels in America Anger Management Animal Kingdom (2016) Anne with an E Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown...Apple Tree Yard Aquarius (2015) Archer (2009) Arrested Development Arrow Ascension Ash vs Evil Dead Atlanta Atypical Avatar The Last Airbender Awkward. Baby Daddy Babylon Berlin Bad Blood (2017) Bad Education Ballers Band of Brothers Banshee Barbarians Rising Barry Bates Motel Battlestar Galactica (2003) Beauty and the Beast (2012) Being Human Berlin Station Better Call Saul Better Things Beyond Big Brother Big Little Lies Big Love Big Mouth Bill Nye Saves the World Billions Bitten Black Lightning Black Mirror Black Sails Blindspot Blood Drive Bloodline Blue Bloods Blue Mountain State Blue Natalie Blue Planet II BoJack Horseman Boardwalk Empire Bobs Burgers Bodyguard (2018) Bones Borgen Bosch BrainDead Breaking Bad Brickleberry Britannia Broad City Broadchurch Broken (2017) Brooklyn Nine-Nine Bull (2016) Bulletproof Burn Notice CSI Crime Scene Investigation CSI Miami CSI NY Cable Girls Californication Call the Midwife Cardinal Carl Webers The Family Busines.. -

Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood

Is There a Woman Behind the Veil? The Use of Clothing, Textiles, and Accessories in Lady Oracle and Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood Marte Storbråten Ytterbøe A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages University of Oslo In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the MA Degree Spring Term 2010 Supervisor: Rebecca Scherr 2 Acknowledgements Writing my master‟s thesis has been an interesting journey and a great learning experience. It has been a privilege to dedicate a year of my life to research and write about two novels by my favourite author, Margaret Atwood. Since Margaret Atwood is a Canadian author, I seized the chance to revisit Canada in September 2009. I have never regretted my research trip to Vancouver and The University of British Columbia. Reference Librarian, Kimberley Hintz, helped me to figure out the library and to find articles which I have later used in this thesis. My parents read for me from an early age, and I owe my interest in literature to them. When I was sixteen, my mother recommended a Canadian novel called Alias Grace. I was as old as Grace was when she was convicted for murder when I read her story, and I fell in love with both Grace and Margaret Atwood at that moment. Professor Jeannette Lynes, writer in residence at Queen‟s University in Kingston, Canada, later inspired me to take a second look at Alias Grace and she helped me develop the early ideas for this thesis. I would like to thank my supervisor Associate Professor Rebecca Scherr for her interest in this project, her help, her ideas, and her patience. -

Abortion Onscreen in 2017 Portrayals of Abortion on American Television

Abortion Onscreen in 2017 Portrayals of Abortion on American Television For those involved in abortion advocacy and provision, 2017 marked a year of both transition and impending setbacks. Abortion portrayals in popular culture have begun to reflect this in small, but resonant, ways. Some of these parallels are realized retrospectively: for example, abortion rights protesters across the country have adopted the cinematic imagery of Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale as particularly appropriate for this moment in history, although the show had already begun filming before last year’s Presidential election, and the novel on which it was based is over thirty years old. Other parallels, though, are deliberate: FX’s American Horror Story: Cult begins with a portrayal of Election Night 2016, and spirals into the horrific from that moment. Regardless of the intentionality, dystopic and disturbing abortion plot lines are having a moment on American television in 2017. In addition to The Handmaid’s Tale (which shows the executed body of an abortion provider in a rigidly conservative new world order) and American Horror Story (which shows a woman dying from a deliberately botched abortion inflicted by a deranged, sadistic, conservative pastor), there were the nightmarish abortions set in the past: Underground’s portrayal of the brutal reproductive coercions that enslaved Black women faced in 1850s Georgia and Alias Grace’s portrayal of the false choice between the heavy stigma of single motherhood and risk of dangerous abortion in 1840s Canada. There are otherwise powerless characters who attempt to make decisions about their reproduction as a way of asserting autonomy (e.g., The White Princess, Orphan Black); there are characters who are forced to get abortions (e.g., Underground, Somewhere Between).