Introducing Non-Referential Concepts to Wordnet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Expressive Interjection Translation in Terms of Meanings

perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id ANALYSIS OF EXPRESSIVE INTERJECTION TRANSLATION IN TERMS OF MEANINGS, TECHNIQUES, AND QUALITY ASSESSMENTS IN “THE VERY BEST DONALD DUCK” BILINGUAL COMICS EDITION 17 THESIS Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Sarjana Degree at English Department of Faculty of Letters and Fine Arts University of Sebelas Maret By: LIA ADHEDIA C0305042 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LETTERS AND FINE ARTS UNIVERSITY OF SEBELAS MARET SURAKARTA 2012 THESIScommit APPROVAL to user i perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id commit to user ii perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id commit to user iii perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id PRONOUNCEMENT Name : Lia Adhedia NIM : C0305042 Stated whole-heartedly that this thesis entitled Analysis of Expressive Interjection Translation in Terms of Meanings, Techniques, and Quality Assessments in “The Very Best Donald Duck” bilingual comics edition 17 is originally made by the researcher. It is neither a plagiarism, nor made by others. The things related to other people’s works are written in quotation and included within bibliography. If it is then proved that the researcher cheats, the researcher is ready to take the responsibility. Surakarta, May 2012 The researcher Lia Adhedia C0305042 commit to user iv perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id MOTTOS “Allah does not change a people’s lot unless they change what their hearts is.” (Surah ar-Ra’d: 11) “So, verily, with every difficulty, there is relief.” (Surah Al Insyirah: 5) commit to user v perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to My beloved mother and father My beloved sister and brother commit to user vi perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id ACKNOWLEDGMENT Alhamdulillaahirabbil’aalamiin, all praises and thanks be to Allah, and peace be upon His chosen bondsmen and women. -

TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional

Traditional Grammar Review Page 1 of 15 TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional grammar recognizes eight parts of speech: Part of Definition Example Speech noun A noun is the name of a person, place, or thing. John bought the book. verb A verb is a word which expresses action or state of being. Ralph hit the ball hard. Janice is pretty. adjective An adjective describes or modifies a noun. The big, red barn burned down yesterday. adverb An adverb describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or He quickly left the another adverb. room. She fell down hard. pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. She picked someone up today conjunction A conjunction connects words or groups of words. Bob and Jerry are going. Either Sam or I will win. preposition A preposition is a word that introduces a phrase showing a The dog with the relation between the noun or pronoun in the phrase and shaggy coat some other word in the sentence. He went past the gate. He gave the book to her. interjection An interjection is a word that expresses strong feeling. Wow! Gee! Whew! (and other four letter words.) Traditional Grammar Review Page 2 of 15 II. Phrases A phrase is a group of related words that does not contain a subject and a verb in combination. Generally, a phrase is used in the sentence as a single part of speech. In this section we will be concerned with prepositional phrases, gerund phrases, participial phrases, and infinitive phrases. Prepositional Phrases The preposition is a single (usually small) word or a cluster of words that show relationship between the object of the preposition and some other word in the sentence. -

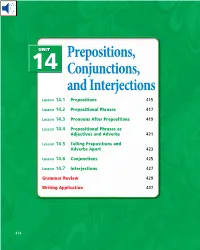

Prepositions, Conjunctions, and Interjections System of Classifying Books

UNIT Prepositions, 14 Conjunctions, and Interjections Lesson 14.1 Prepositions 415 Lesson 14.2 Prepositional Phrases 417 Lesson 14.3 Pronouns After Prepositions 419 Lesson 14.4 Prepositional Phrases as Adjectives and Adverbs 421 Lesson 14.5 Telling Prepositions and Adverbs Apart 423 Lesson 14.6 Conjunctions 425 Lesson 14.7 Interjections 427 Grammar Review 429 Writing Application 437 414 414_P2U14_888766.indd 414 3/18/08 12:21:23 PM 414-437 wc6 U14 829814 1/15/04 8:14 PM Page 415 14.114.1 Prepositions ■ A preposition is a word that relates a noun or a pronoun to some other word in a sentence. The dictionary on the desk was open. An almanac was under the dictionary. Meet me at three o’clock tomorrow. COMMONLY USED PREPOSITIONS aboard as despite near since about at down of through above before during off to across behind except on toward after below for onto under against beneath from opposite until Prepositions, Conjunctions, and Interjections along beside in out up amid between inside outside upon among beyond into over with around by like past without A preposition can consist of more than one word. I borrowed the almanac along with some other reference books. PREPOSITIONS OF MORE THAN ONE WORD according to along with because of in spite of on top of across from aside from in front of instead of out of Read each sentence below. Any word that fits in the blank is a preposition. Use the almanac that is the table. I took the atlas your room. 14.1 Prepositions 415 414-437 wc6 U14 829814 1/15/04 8:15 PM Page 416 Exercise 1 Identifying Prepositions Write each preposition from the following sentences. -

Inflection Rules for English to Marathi Translation

Available Online at www.ijcsmc.com International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing A Monthly Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology ISSN 2320–088X IJCSMC, Vol. 2, Issue. 4, April 2013, pg.7 – 18 RESEARCH ARTICLE Inflection Rules for English to Marathi Translation Charugatra Tidke 1, Shital Binayakya 2, Shivani Patil 3, Rekha Sugandhi 4 1,2,3,4 Computer Engineering Department, University Of Pune, MIT College of Engineering, Pune-38, India [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract— Machine Translation is one of the central areas of focus of Natural Language Processing where translation is done from Source Language to Target Language preserving the meaning of the sentence. Large amount of research is being done in this field. However, research in Machine Translation remains highly localized to the particular source and target languages due to the large variations in the syntactical construction of languages. Inflection is an important part to get the correct translation. Inflection is basically the adding of appropriate suffix to the word according to the sentence structure to obtain the meaningful form of the word. This paper presents the implementation of the Inflection for English to Marathi Translation. The inflection of Nouns, Pronouns, Verbs, Adjectives are done on the basis of the other words and their attributes in the sentence. This paper gives the rules for inflecting the above Parts-of-Speech. Key Terms: - Natural Language Processing; Machine Translation; Parsing; Marathi; Parts-Of-Speech; Inflection; Vibhakti; Prataya; Adpositions; Preposition; Postposition; Penn Tags I. INTRODUCTION Machine translation, an integral part of Natural Language Processing, is important for breaking the language barrier and facilitating the inter-lingual communication. -

Applying the Principle of Simplicity to the Preparation of Effective English Materials for Students in Iranian High Schools

APPLYING THE PRINCIPLE OF SIMPLICITY TO THE PREPARATION OF EFFECTIVE ENGLISH MATERIALS FOR STUDENTS IN IRANIAN HIGH SCHOOLS By MOHAMMAD ALI FARNIA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1980 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Professor Arthur J. Lewis, my advisor and chairperson of my dissertation committee, for his valuable guidance, not only in regard to this project, but during my past two years at the Uni- versity of Florida. I believe that without his help and extraordinary patience this project would never have been completed, I am also grateful to Professor Jayne C. Harder, my co-chairperson, for the invaluable guidance and assistance I received from her. I am greatly indebted to her for her keen and insightful comments, for her humane treatment, and, above all, for the confidence and motivation that she created in me in the course of writing this dissertation. I owe many thanks to the members of my doctoral committee. Pro- fessors Robert Wright, Vincent McGuire, and Eugene A. Todd, for their careful reading of this dissertation and constructive criticism. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to my younger brother Aziz Farnia, whose financial support made my graduate studies in the United States possible. My personal appreciation goes to Miss Sofia Kohli ("Superfish") for typing the final version of this dissertation. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS , LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ^ ABSTRACT ^ii CHAPTER I I INTRODUCTION The Problem Statement 3 The Need for the Study 4 Problems of Iranian Students 7 Definition of Terms 11 Delimitations of the Study 17 Organization of the Dissertation 17 II REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 19 Learning Theories 19 Innateness Universal s in Language and Language Learning .. -

Syntactic Cues to the Noun and Verb Distinction in Mandarin Child

FLA0010.1177/0142723719845175First LanguageMa et al. 845175research-article2019 FIRST Article LANGUAGE First Language 1 –29 Syntactic cues to the © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: noun and verb distinction sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723719845175DOI: 10.1177/0142723719845175 in Mandarin child-directed journals.sagepub.com/home/fla speech Weiyi Ma University of Arkansas, USA Peng Zhou Tsinghua University, China Roberta Michnick Golinkoff University of Delaware, USA Joanne Lee Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada Kathy Hirsh-Pasek Temple University, USA Abstract The syntactic structure of sentences in which a new word appears may provide listeners with cues to that new word’s form class. In English, for example, a noun tends to follow a determiner (a/an/the), while a verb precedes the morphological inflection [ing]. The presence of these markers may assist children in identifying a word’s form class and thus glean some information about its meaning. This study examined whether Mandarin, a language that has a relatively impoverished morphosyntactic system, offers reliable morphosyntactic cues to the noun–verb distinction in child-directed speech (CDS). Using the CHILDES Beijing corpora, Study 1 found that Mandarin CDS has reliable morphosyntactic markers to the noun–verb distinction. Study 2 examined the Corresponding authors: Weiyi Ma, School of Human Environmental Sciences, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA. Email: [email protected] Peng Zhou, Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, Tsinghua University, Beijing China. Email: [email protected] 2 First Language 00(0) relationship between mothers’ use of a set of early-acquired nouns and verbs in the Beijing corpora and the age of acquisition (AoA) of these words. -

The Semantics of Onomatopoeic Speech Act Verbs

The Semantics of Onomatopoeic Speech Act Verbs I-Ni Tsai Chu-Ren Huang Institute of Linguistics (Preparatory Office), Institute of Linguistics (Preparatory Office), Academia Sinica Academia Sinica No. 128 Academic Sinica Road, Sec 2. No. 128 Academic Sinica Road, Sec 2. Nangkang, Taipei 115, Taiwan Nangkang, Taipei 115, Taiwan [email protected] [email protected] Abstract This paper attempts to explore the semantics of onomatopoeic speech act verbs. Language abounds with small bits of utterances to show speaker's emotions, to maintain the flow of speech and to do some daily exchange routines. These tiny vocalizations have been regarded as vocal gestures and largely studied under the framework of 'interjection'. In this paper, the emphasis is placed on the perlocutionary force the vocal tokens contain. We describe their conventionalized lexical meaning and term them as onomatopoeic speech act verb. An onomatopoeic speech act verb refers to a syntactically independent monomorphemic utterance which performs illocutionary or perlocutionary forces. It is normally directed at the listener, which making the recipient to do something or to solicit recipient's response or reaction. They are onomatopoeic because most of them are imitation of the sounds produced by doing some actions. 1 Introduction Based on the Speech Act Theory (Austin 1992; Reiss 1985; Searle 1969, 1975, 1979), speech act is what speaker performs when producing the utterance. Researchers suggest that speech act is not only an utterance act but contains the perlocutionary force. If the speaker has some particular intention when making the utterance such as committing to doing something or expressing attitude or emotions, the speech act is said to contain illocutionary force. -

Chapter 2 from Elly Van Geldern 2017 Minimalism Building Blocks This

Chapter 2 From Elly van Geldern 2017 Minimalism Building blocks This chapter reviews the lexical and grammatical categories of English and provides criteria on how to decide whether a word is, for example, a noun or an adjective or a demonstrative. This knowledge of categories, also known as parts of speech, can then be applied to languages other than English. The chapter also examines pronouns, which have grammatical content but may function like nouns, and looks at how categories change. Categories continue to be much discussed. Some linguists argue that the mental lexicon lists no categories, just roots without categorial information, and that morphological markers (e.g. –ion, -en, and zero) make roots into categories. I will assume there are categories of two kinds, lexical and grammatical. This distinction between lexical and grammatical is relevant to a number of phenomena that are listed in Table 2.1. For instance, lexical categories are learned early, can be translated easily, and be borrowed because they have real meaning; grammatical categories do not have lexical meaning, are rarely borrowed, and may lack stress. Switching between languages (code switching) is easier for lexical than for grammatical categories. Lexical Grammatical First Language Acquisition starts with lexical Borrowed grammatical categories are rare: categories, e.g. Mommy eat. the prepositions per, via, and plus are the rare borrowings. Lexical categories can be translated into another language easily. Grammatical categories contract and may lack stress, e.g. He’s going for he is going. Borrowed words are mainly lexical, e.g. taco, sudoko, Zeitgeist. Code switching between grammatical categories is hard: Code switching occurs: I saw adelaars *Ik am talking to the neighbors. -

English for Practical Purposes 9

ENGLISH FOR PRACTICAL PURPOSES 9 CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction of English Grammar Chapter 2: Sentence Chapter 3: Noun Chapter 4: Verb Chapter 5: Pronoun Chapter 6: Adjective Chapter 7: Adverb Chapter 8: Preposition Chapter 9: Conjunction Chapter 10: Punctuation Chapter 11: Tenses Chapter 12: Voice Chapter 1 Introduction to English grammar English grammar is the body of rules that describe the structure of expressions in the English language. This includes the structure of words, phrases, clauses and sentences. There are historical, social, and regional variations of English. Divergences from the grammardescribed here occur in some dialects of English. This article describes a generalized present-dayStandard English, the form of speech found in types of public discourse including broadcasting,education, entertainment, government, and news reporting, including both formal and informal speech. There are certain differences in grammar between the standard forms of British English, American English and Australian English, although these are inconspicuous compared with the lexical andpronunciation differences. Word classes and phrases There are eight word classes, or parts of speech, that are distinguished in English: nouns, determiners, pronouns, verbs, adjectives,adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions. (Determiners, traditionally classified along with adjectives, have not always been regarded as a separate part of speech.) Interjections are another word class, but these are not described here as they do not form part of theclause and sentence structure of the language. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs form open classes – word classes that readily accept new members, such as the nouncelebutante (a celebrity who frequents the fashion circles), similar relatively new words. The others are regarded as closed classes. -

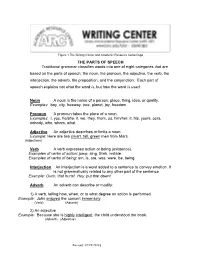

THE PARTS of SPEECH Traditional Grammar Classifies Words Into One

Figure 1 The Writing Center and Academic Resource Center logo THE PARTS OF SPEECH Traditional grammar classifies words into one of eight categories that are based on the parts of speech: the noun, the pronoun, the adjective, the verb, the interjection, the adverb, the preposition, and the conjunction. Each part of speech explains not what the word is, but how the word is used. Noun A noun is the name of a person, place, thing, idea, or quality. Examples: boy, city, freeway, tree, planet, joy, freedom Pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. Examples: I, you, he/she, it, we, they, them, us, him/her, it, his, yours, ours, nobody, who, whom, what Adjective An adjective describes or limits a noun. Example: Here are two smart, tall, green men from Mars. (Adjectives) Verb A verb expresses action or being (existence). Examples of verbs of action: jump, sing, think, imitate. Examples of verbs of being: am, is, are, was, were, be, being Interjection An interjection is a word added to a sentence to convey emotion. It is not grammatically related to any other part of the sentence. Example: Ouch, that hurts! Hey, put that down! Adverb An adverb can describe or modify: 1) A verb, telling how, when, or to what degree an action is performed. Example: John enjoyed the concert immensely. (Verb) (Adverb) 2) An adjective Example: Because she is highly intelligent, the child understood the book. (Adverb) (Adjective) Revised: 07/25/20181 3) Another adverb Example: The pedestrian ran across the street very rapidly. (Verb) (Adverb) (The adverb “rapidly” modifies the verb “ran,” and the adverb “very” modifies the adverb “rapidly.”) Preposition A word that shows the relation of a noun or pronoun to some other word in the sentence. -

I Will Wow You! Pragmatic Interjections Revisited

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CSCanada.net: E-Journals (Canadian Academy of Oriental and Occidental Culture,... STUDIES IN LITERATURE AND LANGUAGE ISSN 1923-1555 [Print] Vol. 2, No. 1, 2011, pp. 57-67 ISSN 1923-1563 [Online] www.cscanada.net www.cscanada.org I Will Wow You! Pragmatic Interjections Revisited Tahmineh Tayebi1 Vahid Parvaresh2 Abstract: This study sets out to focus on the nature of changes some major interjections have gone through. To achieve this end, different processes of word formation and semantic change are put under scrutiny. In this vein, the significant role of frequency and the gradual movement of these changes are underscored. Additionally, the study demonstrates how what is generally known as reanalysis can account for functional shifts. The study also touches upon what is usually described as innovation. Key words: Innovation; Interjection; Reanalysis; Semantic change. INTRODUCTION Historically, interjections have been regarded as marginal to language. Latin grammarians described them as non-words, independent of syntax, signifying only feelings or states of mind (Wharton, 2003). Nineteenth-century linguists regarded them as paralinguistic, even non-linguistic phenomena. They believed that “between interjection and word there is a chasm wide enough to allow us to say that interjection is the negation of language” (Benfey, 1869, p. 295), or that “language begins where interjections end” (Müller, 1862, p. 366). Accordingly, interjections have been regarded as the words or phrases that have expressive functions or, in other words, are mostly used to express the speaker’s feelings or emotions. -

Genders and Classifiers OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 26/07/19, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 26/07/19, SPi Genders and Classifiers OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 26/07/19, SPi EXPLORATIONS IN LINGUISTIC TYPOLOGY general editors: Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon Language and Culture Research Centre, James Cook University This series focuses on aspects of language that are of current theoretical interest and for which there has not previously or recently been any full-scale cross-linguistic study. Its books are for typologists, fieldworkers, and theory developers, and designed for use in advanced seminars and courses. published 1 Adjective Classes edited by R. M. W. Dixon and Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald 2 Serial Verb Constructions edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon 3 Complementation edited by R. M. W. Dixon and Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald 4 Grammars in Contact edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon 5 The Semantics of Clause Linking edited by R. M. W. Dixon and Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald 6 Possession and Ownership edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon 7 The Grammar of Knowledge edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon 8 Commands edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon 9 Genders and Classifiers edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and Elena I. Mihas published in association with the series Areal Diffusion and Genetic Inheritance Problems in Comparative Linguistics edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 26/07/19, SPi Genders and Classifiers A Cross-Linguistic Typology Edited by ALEXANDRA Y. AIKHENVALD and ELENA I.