Master's Thesis FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harshal Santosh Sonawane DEVELOPMENT of VIRTUAL

VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF INFORMATICS DEPARTMENT OF APPLIED INFORMATICS DEPARTMENT OF SYSTEM ANALYSIS Harshal Santosh Sonawane DEVELOPMENT OF VIRTUAL REALITY SIMULATION PROTOTYPE FOR MILITARY Bachelor Thesis Informatics Systems study programme, state code 612I13003 Study field Informatics Supervisor Prof. Edgaras Ščiglinskas degree, name, surname signature, date Defended Prof. dr. Daiva Vitkutė-Adžgauskienė Dean of Faculty signature, date Kaunas, 2020 Contents 1.INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 7 2. ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS VIRTUAL REALITY SIMULATORS ....................................... 11 2.1 ARMA 3 VR Simulator .................................................................................................. 11 2.2 Analysis of Simulators ................................................................................................... 18 2.3 Comparative Analysis of Virtual Reality Headsets ........................................................ 19 3. DESIGN OF SIMULATION ..................................................................................................... 21 3.1 Functional requirements ................................................................................................. 21 3.2 Technical Requirements ................................................................................................. 22 3.3 Structure of application ................................................................................................. -

Brochure Bohemia Interactive Company

COMPANY BROCHURE NOVEMBER 2018 Bohemia Interactive creates rich and meaningful gaming experiences based on various topics of fascination. 0102 BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE By opening up our games to users, we provide platforms for people to explore - to create - to connect. BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE 03 INTRODUCTION Welcome to Bohemia Interactive, an independent game development studio that focuses on creating original and state-of-the-art video games. 0104 BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE Pushing the aspects of simulation and freedom, Bohemia Interactive has built up a diverse portfolio of products, which includes the popular Arma® series, as well as DayZ®, Ylands®, Vigor®, and various other kinds of proprietary software. With its high-profile intellectual properties, multiple development teams across several locations, and its own motion capturing and sound recording studio, Bohemia Interactive has grown to be a key player in the PC game entertainment industry. BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE 05 COMPANY PROFILE Founded in 1999, Bohemia Interactive released its first COMPANY INFO major game Arma: Cold War Assault (originally released as Founded: May 1999 Operation Flashpoint: Cold War Crisis*) in 2001. Developed Employees: 400+ by a small team of people, and published by Codemasters, Offices: 7 the PC-exclusive game became a massive success. It sold over 1.2 million copies, won multiple industry awards, and was praised by critics and players alike. Riding the wave of success, Bohemia Interactive created the popular expansion Arma: Resistance (originally released as Operation Flashpoint: Resistance*) released in 2002. Following the release of its debut game, Bohemia Interactive took on various ambitious new projects, and was involved in establishing a successful spin-off business in serious gaming 0106 BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE *Operation Flashpoint® is a registered trademark of Codemasters. -

Historie Herního Vývojářského Studia Bohemia Interactive

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Teorie Interaktivních Médií Philip Hilal Bakalářská diplomová práce: Historie herního vývojářského studia Bohemia Interactive Vedoucí práce: Mgr. et Mgr. Zdeněk Záhora Brno 2021 2. Prohlášení o samostatnosti: Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma Historie herního vývojářského studia Bohemia Interactive vypracoval samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů literatury a rozhovorů. Souhlasím, aby práce byla uložena na Masarykově univerzitě v Brně v knihovně Filozofické fakulty a zpřístupněna ke studijním účelům. ………...……………………… V Brně dne 13. 01. 2021 Philip Hilal 2 3. Poděkování: Považuji za svoji milou povinnost poděkovat vedoucímu práce Mgr. et Mgr. Zdeňku Záhorovi za odborné a organizační vedení při zpracování této práce. Také bych rád poděkoval vedení a zaměstnancům společnosti Bohemia Interactive, jmenovitě Marku Španělovi a Ivanu Buchtovi, za poskytnuté informace a pomoc při tvorbě této práce. 3 4. Osnova: 1. Titulní Strana ................................................................................................. 1 2. Prohlášení o samostatnosti ........................................................................... 2 3. Poděkování .................................................................................................... 3 4. Osnova ........................................................................................................... 4 5. Abstrakt a klíčová slova ................................................................................ -

Creación De Juegos Serios En Unity 3D

TRABAJO DE FIN DE MASTER EN SISTEMAS INTELIGENTES MASTER EN INVESTIGACIÓN EN INFORMÁTICA FACULTAD DE INFORMÁTICA UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Creación de Juegos Serios en Unity 3D Autor: MATE ANTIČEVIĆ Director: Iván Martínez Ortiz Curso Académico: 2013-14 Calificación Obtenida: Sobresaliente Madrid, Junio 2014 Creating serious games in Unity3D | I This page is intentionally left blank II | Mate Antičević Creating serious games in Unity3D | III El/la abajo firmante, matriculado/a en el Master en Investigación en Informática de la Facultad de Informática, autoriza a la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM) a difundir y utilizar con fines académicos, no comerciales y mencionando expresamente a su autor el presente Trabajo Fin de Máster: “Creating Serious Games in Unity 3D”, realizado durante el curso académico 2013-2014 bajo la dirección de Dr. Iván Martínez Ortiz en el Departamento de Ingeniería del Software e Inteligencia Artificial, y a la Biblioteca de la UCM a depositarlo en el Archivo Institucional E-Prints Complutense con el objeto de incrementar la difusión, uso e impacto del trabajo en Internet y garantizar su preservación y acceso a largo plazo. MATE ANTIČEVIĆ Madrid, 23 de junio de 2014 Director: Iván Martínez Ortiz IV | Mate Antičević Creating serious games in Unity3D | V ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Iván Martínez-Ortiz for his support and effort put into this work, by providing corrections and suggestions. His experience in the field was essential for completing this work. I would also like to thank the whole team behind the e-Adventure project for providing me with a high level game authoring tool perfect for use in this thesis. -

Tekan Bagi Yang Ingin Order Via DVD Bisa Setelah Mengisi Form Lalu

DVDReleaseBest 1Seller 1 1Date 1 Best4 15-Nov-2013 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 1 1-Dec-2014 1 Seller 1 2 1 Best1 1 30-Nov-20141 Seller 1 6 2 Best 4 1 9 Seller29-Nov-2014 2 1 1 1Best 1 1 Seller1 28-Nov-2014 1 1 1 Best 1 1 9Seller 127-Nov-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 326-Nov-2014 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 1 25-Nov-20141 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 24-Nov-2014Best1 1 1 Seller 1 2 1 1 Best23-Nov- 1 1 1Seller 8 1 2 142014Best 3 1 Seller22-Nov-2014 1 2 6Best 1 1 Seller2 121-Nov-2014 1 2Best 2 1 Seller8 2 120-Nov-2014 1Best 9 11 Seller 1 1 419-Nov-2014Best 1 3 2Seller 1 1 3Best 318-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 17-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 1 1 Best 1 1 16-Nov-20141Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 15-Nov-2014 1 1 1Best 2 1 Seller1 1 14-Nov-2014 1 1Best 1 1 Seller2 2 113-Nov-2014 5 Best1 1 2 Seller 1 1 112- 1 1 2Nov-2014Best 1 2 Seller1 1 211-Nov-2014 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best110-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 2 Best1 9-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 18-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 3 2Best 17-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 6-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 2 1 Best1 4-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 14-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 13-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 1 13-Nov-2014Best 1 1 Seller1 1 1 Best12-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 2-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 3 1 1 Best1 1-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best5 1-Nov-20141 2 Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 31-Oct-20141 1Seller 1 2 1 Best 1 1 31-Oct-2014 1Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 31-Oct-2014Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 Seller 131-Oct-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 30-Oct-20141 1 Best 1 3 1Seller 1 1 30-Oct-2014 1 Best1 -

No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

NEW RELEASES (gunakan tombol CTRL + F untuk mencari judul) JIKA JUDUL GAME YANG ANDA CARI TIDAK ADA DI NEW RELEASES SILAKAN CEK WORKSHEET LIST GAME A-Z NO 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 8 4 1 3 5 9 2 7 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 62 63 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 2 6 -

Brochure Bohemia Interactive Company 05 2016

COMPANY BROCHURE MAY 2016 Bohemia Interactive creates meaningful and rich gaming experiences based on various topics of human fascination. 0102 BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE By opening up our games to users, we provide platforms for people to explore - to create - to connect. BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE 03 INTRODUCTION Welcome to Bohemia Interactive, an independent game development studio that focuses on creating original and state-of-the-art video games. 0104 BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE Pushing the aspects of simulation and freedom, Bohemia Interactive has built up a diverse portfolio of products, which includes the popular Arma® and Take On® series, DayZ®, and various other kinds of proprietary software. With its high-profi le intellectual properties, multiple development teams across several locations, and its own motion capturing and sound recording studio, Bohemia Interactive has grown in 15 years to be a key player in the PC game entertainment industry. BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE 05 COMPANY PROFILE Founded in 1999, Bohemia Interactive released its fi rst COMPANY INFO major game Arma: Cold War Assault (originally released as Founded: May 1999 Operation Flashpoint: Cold War Crisis*) in 2001. Developed Employees: 250+ by a small team of people, and published by Codemasters, Offi ces: 6 the PC-exclusive game became a massive success. It sold over 1.2 million copies, won multiple industry awards, and was praised by critics and players alike. Riding the wave of success, Bohemia Interactive created the popular expansion Arma: Resistance (originally released as Operation Flashpoint: Resistance*) released in 2002. Following the release of its debut game, Bohemia Interactive took on various ambitious new projects, and was involved in establishing a successful spin-off business in serious gaming 0106 BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE *Operation Flashpoint® is a registered trademark of Codemasters. -

Pclinuxos Magazine Page 1 Table of Contents

PCLinuxOS Magazine Page 1 Table of Contents 3 Welcome From The Chief Editor 4 Download an Entire Picasa Album The PCLinuxOS name, logo and colors are the trademark of 6 Screenshot Showcase Texstar. 7 Avast! Leaves PCLinuxOS Sites Aghast The PCLinuxOS Magazine is a monthly online publication containing PCLinuxOSrelated materials. It is published 9 Screenshot Showcase primarily for members of the PCLinuxOS community. The magazine staff is comprised of volunteers from the 10 ms_meme's Nook: Take Me Home PCLinuxOS community. 11 Hand Of Thief Trojan: More Linux Virus FUD? Visit us online at http://www.pclosmag.com 12 Screenshot Showcase This release was made possible by the following volunteers: 13 PCLinuxOS Puzzled Partitions Chief Editor: Paul Arnote (parnote) 16 Xfce Power User Tips, Tricks & Tweaks: Assistant Editor: Meemaw Artwork: Sproggy, Timeth, ms_meme, Meemaw Xfce's Builtin Wallpaper Slideshow Made Easy Magazine Layout: Paul Arnote, Meemaw, ms_meme 19 Screenshot Showcase HTML Layout: YouCanToo 20 PCLinuxOS Family Member Spotlight: Bubba Blues Staff: ms_meme Mark Szorady 21 Game Zone: Arma Tactics Patrick Horneker Darrel Johnston Meemaw Andrew Huff 23 Screenshot Showcase Gary L. Ratliff, Sr. Pete Kelly Daniel MeißWilhelm Antonis Komis 24 Keepassx: Not In The Cloud AndrzejL daiashi 27 Encrypting Your Email In Thunderbird YouCanToo Contributors: 30 Mailvelope OpenPGP Encryption For Webmail Yankee Smileeb 35 Inkscape: Tree Silhouette In Sunset, Part 2 39 PCLinuxOS Recipe Corner The PCLinuxOS Magazine is released under the Creative 40 Root Out Root Kits With rkhunter Commons AttributionNonCommercialShareAlike 3.0 Unported license. Some rights are reserved. 46 Blocking Sites For A More Secure Browsing Experience Copyright © 2013. -

Historie Herního Vývojářského Studia Bohemia Interactive

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Teorie Interaktivních Médií Philip Hilal Bakalářská diplomová práce: Historie herního vývojářského studia Bohemia Interactive Vedoucí práce: Mgr. et Mgr. Zdeněk Záhora Brno 2020 2. Prohlášení o samostatnosti: Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma Historie Společnosti Bohemia Interactive vypracoval samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů literatury a rozhovorů. Souhlasím, aby práce byla uložena na Masarykově univerzitě v Brně v knihovně Filozofické fakulty a zpřístupněna ke studijním účelům. ………...……………………… V Brně dne 12. 12. 2020 Philip Hilal 2 3. Poděkování: Považuji za svoji milou povinnost poděkovat vedoucímu práce Mgr. et Mgr. Zdeňkovi Záhorovi za odborné a organizační vedení při zpracování této práce. Také bych rád poděkoval vedení a zaměstnancům společnosti Bohemia Interactive, jmenovitě Marku Španělovi a Ivanu Buchtovi, za poskytnuté informace a pomoc při tvorbě této práce. 3 4. Osnova: 1. Titulní Strana ................................................................................................. 1 2. Prohlášení o původnosti autora .................................................................... 2 3. Poděkování – Škola, Bohemia Interactive .................................................... 3 4. Osnova ........................................................................................................... 4 5. Abstrakt a klíčová slova ................................................................................. 5 6. Předmluva .................................................................................................... -

Armed Assault Iso Download

Armed assault iso download Download ArmA: Armed Assault • Windows Games @ The Iso Zone • The Ultimate Retro Gaming Resource. Download Armored Assault • Windows Games @ The Iso Zone • The Ultimate Retro Gaming Resource. Download Armed Assault Queens Gambit Expansion • Game Addons & Mods @ The Iso Zone • The Ultimate Retro Gaming Resource. ARMA Armed Assault Download new game pc iso, Repack pc game, Crack game pc gog, Direct link game pc, Download full iso game pc vr. Armed Assault, free and safe download. Armed Assault latest version: Highly realistic battles in this tactical military first person shooter. Armed Assault is an. ArmA: Armed Assault (PC/ENG/ISO) Year | PC game | English | Developer: Bohemia Interactive | Gb Genre: 1st Person Shooter. How To Get Arma Armed Assault Free!!! Arma#F!OxpnRDLS! Power Isohttp. Download Arma: Armed Assault Free PC Game Full Version - Duration: Judith Martin 1, views · Free Download Game PC Via MediaFire EnterUpload MegaUpload HotFile FileSonic FileServe RapidShare Indowebster Google, Download games gratis. Assault, like Flashpoint, shines brightest when combined with quality Download ArmA Armed Assault • Windows Games @ The Iso Zone Ultimate Retro. Here list plan All Weapons interactive. Download ArmA Assault • Windows Games @ The Iso Zone Ultimate Retro Gaming Resource II is first-. ARMA: Armed Assault Overview. ARMA: Armed Assault, also known as ARMA: Combat Operations in North America, is a tactical military shooter game which. (MB). t Torrent sites: 1. (GB). tali Torrent sites: 1. (GB). armed Torrent sites: 1. (MB). arma. armed assault Gold [Repack].iso Torrent sites: 1. (MB). t+ Torrent sites: 1. (GB). arma: armed. Counter Strike Go Highly Compressed Game Free Download Full Version For Pc. -

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

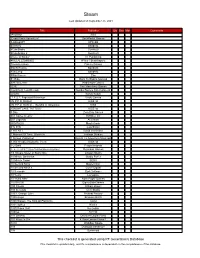

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Brochure Bohemia Interactive Company 10 2017.Indd

COMPANY BROCHURE OCTOBER 2017 Bohemia Interactive creates rich and meaningful gaming experiences based on various topics of fascination. 0102 BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE By opening up our games to users, we provide platforms for people to explore - to create - to connect. BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE 03 INTRODUCTION Welcome to Bohemia Interactive, an independent game development studio that focuses on creating original and state-of-the-art video games. 0104 BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE Pushing the aspects of simulation and freedom, Bohemia Interactive has built up a diverse portfolio of products, which includes the popular Arma® and Take On® series, DayZ®, and various other kinds of proprietary software. With its high-profi le intellectual properties, multiple development teams across several locations, and its own motion capturing and sound recording studio, Bohemia Interactive has grown to be a key player in the PC game entertainment industry. BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE 05 COMPANY PROFILE Founded in 1999, Bohemia Interactive released its fi rst COMPANY INFO major game Arma: Cold War Assault (originally released as Founded: May 1999 Operation Flashpoint: Cold War Crisis*) in 2001. Developed Employees: 300+ by a small team of people, and published by Codemasters, Offi ces: 7 the PC-exclusive game became a massive success. It sold over 1.2 million copies, won multiple industry awards, and was praised by critics and players alike. Riding the wave of success, Bohemia Interactive created the popular expansion Arma: Resistance (originally released as Operation Flashpoint: Resistance*) released in 2002. Following the release of its debut game, Bohemia Interactive took on various ambitious new projects, and was involved in establishing a successful spin-off business in serious gaming 0106 BOHEMIA INTERACTIVE BROCHURE *Operation Flashpoint® is a registered trademark of Codemasters.