Space and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edinburgh, C. 1710–70

Edinburgh Research Explorer Credit, reputation, and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh, c. 1710–70 Citation for published version: Paul, T 2013, 'Credit, reputation, and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh, c. 1710–70', The Economic History Review, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 226-248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00652.x Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00652.x Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Economic History Review Publisher Rights Statement: © Paul, T. (2013). Credit, reputation, and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh, c. 1710–70. The Economic History Review, 66(1), 226-248. 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00652.x General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 © Paul, T. (2013). Credit, reputation, and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh, c. 1710–70. The Economic History Review, 66(1), 226-248. 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00652.x Credit, reputation and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh c. -

Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Monday 10 July 2017 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Monday 10 July 2017 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Monday 10 July 2017 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Monday 10 July 2017 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 26 June 2017 Tuesday 5 September 2017 2:00 pm Time for Reflection followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by Scottish Government Business followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' Business Wednesday 6 September 2017 2:00 pm Parliamentary Bureau Motions 2:00 pm Portfolio Questions Finance and Constitution; Economy, Jobs and Fair Work followed by Scottish Government Business followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' -

The European Cities Hotel Forecast 23 Appendix: Methodology 43 Contacts 47

www.pwc.com/hospitality Best placed to grow European cities hotel forecast 2011 & 2012 October 2011 NEW hotel forecast for 17 European cities In this issue Introduction 4 Key findings 5 Setting the scene 6 The cities best placed to grow 7 Economic and travel outlook 15 The European cities hotel forecast 23 Appendix: methodology 43 Contacts 47 PwC Best placed to grow 3 Introduction Europe has the biggest hotel and travel market in the world, but its cities and its hotel markets are undergoing change. Countries and cities alike are being buffeted by new economic, social, technological, environmental and political currents. Europe has already begun to feel the winds of change as the old economic order shifts eastwards and economic growth becomes more elusive. While some cities struggle, hotel markets in other, often bigger and better connected cities prosper. For many countries provincial markets have been hit harder than those in the larger cities. In this report we look forward to 2012 and ask which European cities’ hotel sectors are best placed to take advantage of the changing economic order. Are these the cities of the so called ‘old’ Europe or the cities of the fast growing ‘emerging’ economies such as Istanbul and Moscow? What will be driving the growth? What obstacles do they face? Will the glut of new hotel rooms built in the boom years prove difficult to digest? The 17 cities in this report are all important tourist destinations. Some are capitals or regional centres, some combine roles as leading international financial and asset management centres, transportation hubs or tourism and conference destinations. -

City of Edinburgh Council

SUBMISSION FROM THE CITY OF EDINBURGH COUNCIL INTRODUCTION This submission from the City of Edinburgh Council is provided in response to the Local Government and Communities Committee’s request for views on the proposed National Planning Framework 2. The sections in this statement that refer to the Edinburgh Waterfront are also supported by members of the Edinburgh Waterfront Partnership. To assist the Committee, the Council has prepared a series of proposed modifications to the text of NPF2 which are set out in an Annex. SUMMARY The City of Edinburgh Council welcomes the publication of NPF2 and commends the Scottish Government for the considerable efforts it has made in engaging with key stakeholders throughout the review period. However, the Council requests that NPF2 is modified to take account of Edinburgh’s roles as a capital city and the main driver of the Scottish economy. This is particularly important in view of the current economic recession which has developed since NPF2 was drafted. In this context it is important that Edinburgh’s role is fully recognised in addressing current economic challenges and securing future prosperity. It should also recognise that the sustainable growth of the city-region depends critically on the provision of the full tram network and affordable housing. In addition, the Council considers that the scale and significance of development and change at Edinburgh’s Waterfront is significantly downplayed. As one of the largest regeneration projects in Europe it will be of major benefit to the national economy. The Council also requests some detailed but important modifications to bring NPF2 into line with other Scottish Government policy. -

Market Profile Scotland Contents

Market Profile Scotland Contents Overview of Scotland The Seven Cities of Scotland Summary Overview of Scotland Demographics Youth Employment/ Unemployment in Scotland The population of Scotland has increased each year since 2001 and is now at its highest ever. Currently 345,000 young people in National Records of Scotland (NRS) show that the estimated population of Scotland was employment up by 9,000 over the year 5,327,700 in mid-2014. (Sep-Nov 2014) Population change in Scotland is determined by three key elements: Scotland outperforms the UK on youth employment, youth unemployment and youth inactivity rates – • Birth rates higher youth employment rate (56.3% vs. 52.2%), lower youth unemployment rate (16.4% vs. 17.4%) and • Life expectancy lower youth inactivity rate (32.7% vs. 36.8%). • Net migration Of the age groups, those aged 16-24 have the highest unemployment rate - 17,790 young people aged 16- These are, in turn, influenced by a combination of factors, including the relative levels of 24 were on the claimant count in December 2014, a economic prosperity and opportunity, quality of life and the provision of key public services. decrease of 8,830 (33.2%) over the year. The number of people in employment in Scotland has increased by 50,000 over the past year, reaching a record high of 2,612,000 as recent GDP figures show the fastest annual growth since 2007. Overview of Scotland Economy of Scotland Scotland currently has the highest employment rate, lowest unemployment rate and lowest inactivity rate of all four UK nations. -

Turner & Townsend

EEFW/S5/20/COVID/28 ECONOMY, ENERGY AND FAIR WORK COMMITTEE COVID-19 – impact on Scotland’s businesses, workers and economy SUBMISSION FROM TURNER & TOWNSEND 1. Turner & Townsend is an independent global consultancy business, based in the UK, supporting clients with their capital projects and programmes in the real estate, infrastructure and natural resources sectors. We have 110 offices in 45 countries, with Scottish offices, employing over 200 people, located in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen. We have provided consultancy services on a range of key projects across Scotland including Edinburgh Glasgow (rail) Improvement Programme on behalf of Network Rail, the Hydro (The Event Complex Aberdeen) on behalf of Henry Boot Development’s alongside Aberdeen City Council, the Victoria and Albert museum in Dundee on behalf of Dundee Council, Beauly Denny on behalf of SSE, Edinburgh Tram (post settlement agreement) for City of Edinburgh Council and Edinburgh Airport Capital Expansion Programme. Additionally we are currently involved in a number of key infrastructure projects including the A9 road dualling between Perth and Inverness for Transport Scotland, Edinburgh trams to Newhaven extension for City of Edinburgh Council, the Subway Modernisation Programme on behalf of SPT and the key flood defence scheme in Stonehaven on behalf of Aberdeenshire Council. 2. We are submitting evidence to the Committee to inform its work looking at the support that is being made available to businesses and workers and other measures aimed at mitigating the impact of COVID-19. We want to make the Committee aware of two issues: a. the first in regard to restarting those paused capital construction projects designated within the Critical National Infrastructure (CNI) sectors but deemed non-essential to the national COVID-19 effort and; b. -

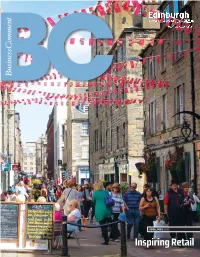

Inspiring Retail

APRIL/MAY 2015 Inspiring Retail February/March 2015 BC 3 Introduction / contents 03 Launch of Inspiring Retail Group 04 10 Successful Festival Trading for Retailers 05 Edinburgh Chamber Importance of the Retail Industry 07 celebrates success at Business Mentoring Scotland 08 our annual Awards Chamber Benefits 09 Edinburgh Chamber Awards 10|13 60 Seconds 23 05 28 Business Stream Appointment 24 Successful Festival An interview with Getting into Retail Management 25 Trading for Retailers Gordon Drummond, Bohemia - A part of Edinburgh’s Mix 26 General Manager at Harvey Nichols A Passion for Retailing 28 Feature: Health and Wellbeing 30|38 Partners in Enterprise 39 Ask the Expert/New Members 40 Inspiring Retail Getting Started 41 Be The Best/Get with IT 42 Retail is business critical to Christmas is one of the latest examples, and in this issue we learn how important that Going International 43 a healthy and diverse Capital event has been in helping retailers at their City. most vital time of year. Chamber Training 44 The retail sector is a major contributor to More than 300 people attended our glittering In the Spotlight 45 our economy through the jobs created, 2015 Business Awards at the Sheraton Grand investment it brings, and a significant driver Hotel. The awards are designed to celebrate Feature: Property 46|51 the enterprise, creativity and excellence of of football both domestically and to meet Inspiring Connections 52|53 the needs of growing visitor numbers. In this our members, so it was entirely appropriate issue we launch our Inspiring Retail Group that the evening was our biggest and best Movers & Shakers 54 highlighting the sector as a strategic priority to date. -

The Potential and Perils of Financial Technology

The Potential and Perils of Financial Technology: Can the Law adapt to cope? The First Edinburgh FinTech Law Lecture, University of Edinburgh Lord Hodge, Justice of the Supreme Court 14 March 2019 “Money is fine, Arron, but data is power”. That is a fictional quotation. But it contains an important truth. The playwright, James Graham, put those words, or words to that effect, into the mouth of Dominic Cummings in a fictional conversation with Arron Banks, the businessman who has funded UKIP and the leave campaign in the Brexit referendum.1 Data is power. So is artificial intelligence. And the theme of my talk this evening is whether, and if so how, law and regulation can cope with the challenges which the use of data and AI by the financial community is posing. There are four technological developments which have created the new opportunities and challenges. They are, first, the huge increase in the computational and data processing power of IT systems. Secondly, data have become available on an unprecedented scale. Thirdly, the costs associated with the storage of data have fallen. And, fourthly, increasingly sophisticated software services have come onto the market. There are various definitions for Artificial Intelligence, or AI, which focus on its ability to perform tasks that otherwise would require human intelligence. Jacob Turner, in his recent book on regulating AI, called “Robot Rules” speaks of AI as “the ability of a non-natural entity to make choices by an evaluative process”.2 That is so, but AI is not confined to matching human intelligence in the performance of its tasks. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for City of Edinburgh Council, 21/11

Public Document Pack Notice of meeting and agenda City of Edinburgh Council 10.00 am Thursday, 21st November, 2019 Main Council Chamber - City Chambers This is a public meeting and members of the public are welcome to attend Contacts Email: [email protected] Tel: 0131 529 4239 1. Order of business 1.1 Including any notices of motion and any other items of business submitted as urgent for consideration at the meeting. 2. Declaration of interests 2.1 Members should declare any financial and non-financial interests they have in the items of business for consideration, identifying the relevant agenda item and the nature of their interest. 3. Deputations 3.1 If any 4. Minutes 4.1 The City of Edinburgh Council of 24 October 2019 – submitted for 17 - 56 approval as a correct record 5. Questions 5.1 By Councillor Osler - Development of the Christmas Market in 57 - 58 East Princes Street Gardens – for answer by the Convener of the Planning Committee 5.2 By Councillor Osler - Strategic Review of Parking – for answer by 59 - 60 the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 5.3 By Councillor Osler - Trial of the Demountable Barrier at Falshaw 61 - 62 Bridge – for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee City of Edinburgh Council - 21 November 2019 Page 2 of 16 5.4 By Councillor Doggart - Princes Street Gardens Christmas Market 63 - 64 and Attractions – for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 5.5 By Councillor Rust - Revenue Spend Through External 65 - 66 Organisations in Each -

Speech by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rt. Hon. Alistair Darling

11 April 2008 Speech by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rt Hon Alistair Darling MP at the Brookings Institution, Washington. Let me start by thanking Strobe Talbott and the Brookings Institution for organising and hosting today's seminar. This weekend, Finance Ministers from the world's major economies have the opportunity to make a difference. Today I want to make the case for urgent action by the world's major economies to deal with what is the biggest economic shock since the Great Depression. And to make the case for reform of our international institutions to meet the challenges of the twenty first century. My starting point is that most problems are capable of resolution if we have the political will to act. That is why I came into politics: we can make a difference if we choose to do so. And this year every country, every government has one aim: to maintain stability through the world economic slowdown and promote global prosperity. But whether it is financial stability: dealing with high food and commodity prices; or indeed ensuring security of energy supplies - if we act together we can deal with these challenges. At the end of the Second World War, nations realised that they had to act together to prevent problems arising in one country spilling over into others. The need for international cooperation is even greater today. As we have seen, problems that arise in one country - the US sub prime market - spread across the world in weeks. But the great institutions set up over sixty years ago - the IMF, the World Bank - were designed for another age. -

The Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism

The Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism This page intentionally left blank The Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism John Tribe AMSTERDAM BOSTON HEIDELBERG LONDON NEW YORK OXFORD PARIS SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO SINGAPORE SYDNEY TOKYO Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington MA 01803 First published 1995 Reprinted 1996, 1997, 1998 Second edition 1999 Reprinted 2000, 2001 Third edition 2004 Copyright © 2004, John Tribe. All rights reserved The right of John Tribe to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 843830; fax: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (www.elsevier.com), -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Policy and Sustainability Committee

Public Document Pack Notice of meeting and agenda Policy and Sustainability Committee 2.00 pm Friday, 25th October, 2019 Dean of Guild Court Room - City Chambers This is a public meeting and members of the public are welcome to attend Contacts Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Tel: 0131 553 8242 / 0131 529 4264 1. Order of Business 1.1 Including any notices of motion and any other items of business submitted as urgent for consideration at the meeting. 2. Declaration of Interests 2.1 Members should declare any financial and non-financial interests they have in the items of business for consideration, identifying the relevant agenda item and the nature of their interest. 3. Deputations 3.1 If any 4. Executive Decisions 4.1 Achieving Net Zero in the City of Edinburgh – Report by Chief 5 - 38 Executive, Executive Director of Place 4.2 Climate Commission – Report by Chief Executive, Executive 39 - 46 Director of Place 4.3 Update on Short Window Improvement Plan – Report by Chief 47 - 96 Executive, Executive Director of Place 4.4 City Strategic Investment Fund – Report by Executive Director of 97 - 108 Place 4.5 Tourism Strategy Development Update – Report by Executive 109 - 126 Director of Place Motions and Amendments Laurence Rockey Head of Strategy and Communications Policy and Sustainability Committee - 25 October Page 2 of 4 2019 Committee Members Councillor Adam McVey (Convener), Councillor Cammy Day (Vice-Convener), Councillor Robert Aldridge, Councillor Jim Campbell, Councillor Kate Campbell, Councillor Neil Gardiner, Councillor Gillian Gloyer, Councillor Graham Hutchison, Councillor Lesley Macinnes, Councillor John McLellan, Councillor Melanie Main, Councillor Ian Perry, Councillor Alasdair Rankin, Councillor Alex Staniforth, Councillor Susan Webber, Councillor Donald Wilson, Councillor Iain Whyte and Councillor Steve Burgess Information about the Policy and Sustainability Committee The Policy and Sustainability Committee consists of 17 Councillors and is appointed by the City of Edinburgh Council.