Resisting Precarity in Toronto's Municipal Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 13, 2013 with amendments. City Council consideration on November 13, 2013 MM41.25 ACTION Amended Ward:All Requesting Mayor Ford to respond to recent events - by Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, seconded by Councillor Peter Milczyn City Council Decision Caution: This is a preliminary decision. This decision should not be considered final until the meeting is complete and the City Clerk has confirmed the decisions for this meeting. City Council on November 13 and 14, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for misleading the City of Toronto as to the existence of a video in which he appears to be involved in the use of drugs. 2. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to co-operate fully with the Toronto Police in their investigation of these matters by meeting with them in order to respond to questions arising from their investigation. 3. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for writing a letter of reference for Alexander "Sandro" Lisi, an alleged drug dealer, on City of Toronto Mayor letterhead. 4. City Council request Mayor Ford to answer to Members of Council on the aforementioned subjects directly and not through the media. 5. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to take a temporary leave of absence to address his personal issues, then return to lead the City in the capacity for which he was elected. 6. City Council request the Integrity Commissioner to report back to City Council on the concerns raised in Part 1 through 5 above in regard to the Councillors' Code of Conduct. -

Can Toronto Be Run Like a Business? Observations on the First Two Years of the Ford Mayoralty in Torontoi

Can Toronto be Run Like a Business? Observations on the First Two Years of the Ford Mayoralty in Torontoi. Richard Stren Cities Centre University of Toronto Prepared for Presentation at the CPSA Annual Conference, Edmonton, Alberta June, 2012 Draft Only. No Citations or References without Express Consent of the Author. Mayoral candidate Rob Ford’s speech at the National Ethnic Press and Media Council of Canada (August 9, 2010): I come from the private sector, where my father started a labeling company….I’m proud to say that with the help of my brothers we have expanded to three locations in New Jersey, Chicago and Rexdale, and we now employ approximately 300 people….What I have seen in the last ten years is very disturbing at City Hall. I’ve seen taxes go up and services go down… In the private sector, we deliver, it’s very simple. The first rule is, the customer is always right. The second rule is, repeat the first rule…In politics we should take the exact same attitude….The taxpayer is the boss of all the civil servants….I really take a business approach to politics…in that customer service is lacking at city hall. …Customer service is number one. Downloaded on May 10, 2012 at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOBotCHFRZE Video interview with Rob Ford on the day before the 2010 election: …[my brother and I have] run my father’s business that he started in 1962. We’ve expanded into Chicago and New Jersey. That’s the business approach I want to take to running the city. -

Remuneration Report Appendix and Attachments

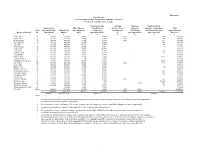

Attachment 1 City of Toronto Summary of Remuneration and Expenses for Members of Council For the year ended December 31, 2020 Expenses from the Corporate Expenses Expenses Paid by Remuneration Office Expenses Council General Business Travel Charged to Agencies, Corporations Total Ward and Benefits (See Support Staff (See Appendices Budget (See (See Appendix City Divisions and Other Bodies (See Remuneration and Member of Council No. Appendix A) Salaries B1, F) Appendices B2, F) C1) (See Appendix D) Appendix C2, E) Expenses $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ Ainslie, Paul 24 147,654 443,918 29,844 17,376 1,844 579 641,215 Bailão, Ana 9 143,254 481,178 13,930 52,703 1,667 349 693,081 Bradford, Brad 19 147,654 479,659 36,241 62,145 1,930 121 727,750 Carroll, Shelley 17 148,260 454,737 23,397 22,060 376 648,831 Colle, Mike 8 128,150 422,517 31,823 38,719 44 621,253 Crawford, Gary 20 147,654 449,990 21,304 18,601 3 637,552 Cressy, Joe 10 147,654 468,989 13,031 105,462 735,136 Filion, John 18 143,169 481,189 30,030 12,881 84 667,353 Fletcher, Paula 14 145,881 465,850 31,082 18,149 389 661,351 Ford, Michael 1 143,254 438,940 19,614 43,058 644,866 Grimes, Mark 3 147,654 427,231 17,748 22,052 5,342 620,027 Holyday, Stephen 2 147,654 303,412 198 13,591 464,855 Karygiannis, Jim (Note 9) 22 91,151 273,994 15,931 13,269 2,545 396,890 Lai, Cynthia 23 148,780 448,702 27,024 41,840 1,430 161 667,937 Layton, Mike 11 147,654 472,441 13,955 19,798 653,848 Matlow, Josh 12 147,654 482,000 17,795 35,742 95 683,286 McKelvie, Jennifer 25 150,979 433,588 26,612 49,358 660,537 Minnan-Wong, -

FALL | 2018 LABOUR ACTION @Torontolabour Facebook.Com/Labourcouncil Labourcouncil.Ca

FALL | 2018 LABOUR ACTION @torontolabour facebook.com/labourcouncil labourcouncil.ca LABOURACTION 3 A LABOUR DAY UNLIKE ANY OTHER It was Labour Day with a difference! For decades, the annual Labour Day parade features thousands of union members from all walks of life taking to the streets and marching to the Canadian National Exhibition. It’s a great way to finish the parade – families taking their kids on the rides, and others quenching their thirst and catching up with friends. But on July 20th the CNE Board of Lamport Stadium instead of the Ex. Governors locked out IATSE Local 58 At the stadium there were childrens members with the intent of busting activities, a beer tent provided by their union agreement. IATSE the Wolfpack Rugby Team, and live members set up and operate sound, music by The Special Interest Group. lighting and audiovisual equipment for We hope this is a once in a lifetime all the shows and sports events at the experience – and that next year we will Ex, and management brought in strike- be back at the Ex where IATSE has a breakers from Alberta and Quebec to fair collective agreement. do their work at the CNE. Shamefully, Thanks to all the marshals and Mayor John Tory fully supported the volunteers, and the Labour Council lockout and blocked attempts by staff who did double duty to make progressive City Councillors to achieve sure the parade went on without a a resolution. (Send him a message at hitch. www.58lockedout.com) LABOUR DAY AWARDS: So Labour Council made other plans. -

Resurrection Support Letter April 2021

April 6, 2021 Councillor Brad Bradford Ward 19 – Beaches East York Toronto City Hall 100 Queen Street West, Suite B28 Toronto, ON M5H 2N2 Dear Councillor Bradford: We are writing to express the support of the Church of the Resurrection for the City’s modular housing project at Cedarvale Avenue and Trenton Avenue in our East York neighbourhood, not far from our church building and the homes of some of our members. We commend you for your leadership in helping to advance this project. Toronto is facing a crisis in homelessness and we must act to care for those most affected. Our faith calls us to care for the poor and those in need. We are a church community that takes this call seriously, and we actively look for ways to be a blessing to our neighbourhood and our City. We are pleased to see this modular housing project being developed in East York to provide housing for up to 64 individuals, and the need is still great. We call on City Council to increase its efforts to address the homelessness crisis in Toronto. We are committed to actively participating with the whole community in creating a safe and caring neighbourhood, and in welcoming the future residents of this housing complex. We will look for practical ways to do so and welcome your suggestions on how we might best contribute to this modular housing project. We look forward to working with you over the course of its development. Sincerely Rev. Julie Burn Incumbent The Church of the Resurrection 1100 Woodbine Ave, Toronto, ON M4C 4C7 (416) 425-8383, www.therez.ca John Amanatides Mary-Lynne Stewart Warden Warden c. -

Item MM37.16

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM37.16 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on July 16, 2013 without amendments. City Council consideration on July 16, 2013 MM37.16 ACTION Adopted Ward:All Protecting the Great Lakes from Invasive Species: Asian Carp - by Councillor Mike Layton, seconded by Councillor Paul Ainslie City Council Decision City Council on July 16, 17, 18 and 19, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council write a letter to the Federal and Provincial Ministers of the Environment strongly urging all parties to work in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to identify a preferred solution to the invasive carp issue and move forward to implement that solution with the greatest sense of urgency. Background Information (City Council) Member Motion MM37.16 (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/bgrd/backgroundfile-60220.pdf) Communications (City Council) (July 10, 2013) Letter from Dr. Terry Quinney, Provincial Manager, Fish and Wildlife Services, Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters (MM.Supp.MM37.16.1) (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/comm/communicationfile-39105.pdf) (July 12, 2013) Letter from Dr. Mark Gloutney, Director of Regional Operations - Eastern Region, Ducks Unlimited Canada (MM.Supp.MM37.16.2) (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/comm/communicationfile-39106.pdf) (July 12, 2013) E-mail from Terry Rees, Executive Director, Federation of Ontario Cottagers' Association (MM.Supp.MM37.16.3) (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/comm/communicationfile-39097.pdf) (July 16, 2013) Letter from Bob Kortright, Past President, Toronto Field Naturalists (MM.New.MM37.16.4) (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/comm/communicationfile-39184.pdf) Motions (City Council) Motion to Waive Referral (Carried) Speaker Nunziata advised Council that the provisions of Chapter 27, Council Procedures, require that Motion MM37.16 be referred to the Executive Committee. -

Funding Arts and Culture Top-10 Law Firms

TORONTO EDITION FRIDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2016 Vol. 20 • No. 49 2017 budget overview 19th annual Toronto rankings FUNDING ARTS TOP-10 AND CULTURE DEVELOPMENT By Leah Wong LAW FIRMS To meet its 2017 target of $25 per capita spending in arts and culture council will need to, not only waive its 2.6 per cent reduction target, but approve an increase of $2.2-million in the It was another busy year at the OMB for Toronto-based 2017 economic development and culture budget. appeals. With few developable sites left in the city’s growth Economic development and culture manager Michael areas, developers are pushing forward with more challenging Williams has requested a $61.717-million net operating proposals such as the intensifi cation of existing apartment budget for 2017, a 3.8 per cent increase over last year. neighbourhoods, the redevelopment of rental apartments with Th e division’s operating budget allocates funding to its implications for tenant relocation, and the redevelopment of four service centres—art services (60 per cent), museum and existing towers such as the Grand Hotel, to name just a few. heritage services (18 per cent), business services (14 per cent) While only a few years ago a 60-storey tower proposal and entertainment industries services (8 per cent). may have seemed stratospheric, the era of the supertall tower One of the division’s major initiatives for 2017 is the city’s has undeniably arrived. In last year’s Toronto law review, the Canada 150 celebrations. At the end of 2017 with the Canada 82- and 92-storey Mirvish + Gehry towers were the tallest 150 initiatives completed, $4.284-million in one-time funding buildings brought before the board. -

Toronto Endorsees2018- Tabloid

Labour Council Endorsed Toronto Candidates 2018 Toronto Disrict School Board Toronto Jennifer Keesmaat Amber Morley Gord Perks Lekan Olawoye Maria Augimeri Ali Mohamed-Ali Shawn Rizvi Matias de Dovitiis Robin Pilkey Stephanie Donaldson Mayor Ward 2 Etobicoke Lakeshore Ward 4 Parkdale High Park Ward 5 York South Weston Ward 6 York Centre Ward 1 Etobicoke North Ward 2 Etobicoke Centre Ward 4 Humber River Black Creek Ward 7 Parkdale High Park Ward 9 Davenport Spadina jenniferkeesmaat.com morewithmorley.com votegordperks.ca lekan.ca mariaaugimeri.ca electmohamedali.ca voterizvi.ca matiasdedovitiis.ca robinpilkey.com Fort York stephaniedonaldson.ca Anthony Perruzza Ana Bailão Joe Cressy Mike Layton Joe Mihevc Chris Moise Amara Possian Siham Rayale Jennifer Story Phil Pothen Ward 7 Humber River Black Creek Ward 9 Davenport Ward 10 Spadina Fort York Ward 11 University Rosedale Ward 12 St. Paul’s Ward 10 Toronto Centre Ward 11 Don Valley West Ward 13 Don Valley North Ward 15 Danforth Ward 16 Beaches East York voteanthonyperruzza.com votebailao.ca joecressy.ca mikelayton.ca joemihevc.ca University Rosedale voteamara.ca votesiham.ca jenniferstory.ca philpothen.ca chrismoise.ca Toronto City Council Toronto Kristyn Wong-Tam Paula Fletcher Shelley Carroll Saman Tabasinejad Matthew Kellway David Smith Parthi Kandavel Samiya Abdi Manna Wong Yalini Rajakulasingam Ward 13 Toronto Centre Ward 14 Toronto Danforth Ward 17 Don Valley North Ward 18 Willowdale Ward 19 Beaches East York Ward 17 Scarborough Centre Ward 18 Scarborough Southwest Ward 19 Scarborough -

Toronto City Summit Alliance Steering Committee

For immediate release Politicians urged to tackle traffic woes 87% of residents say public transit should be regional spending priority Toronto – April 29, 2014 – On the eve of a new provincial budget, a majority of residents in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) say they are more likely to vote for politicians who support new, dedicated dollars to get us moving. That’s the message CivicAction and a coalition of nearly two dozen business, labour, health, community, and environmental groups are delivering to Ontario MPPs and party leaders. The group points to the results of an April Angus Reid Forum poll* showing that 87% of GTHA residents want to see transportation as a regional spending priority, and 83% said they would more likely support new taxes or fees if they were put into a dedicated fund for transportation. Half of the GTHA’s elected officials - including more than 50% of MPPs across the three major political parties - have signed CivicAction’s “Get a Move On” pledge that calls for dedicated, efficient, and sustainable investment in our regional transportation priorities. They have been joined by thousands of GTHA residents. **See the full list below of politicians who have signed the CivicAction pledge. CivicAction and its partners are looking to all of Ontario’s party leaders to be clear on how they will invest in the next wave of transportation improvements for the region – both in the spring budget and in their party platforms. Quotes: “We cannot pass the buck for our aging infrastructure to the next generation,” says Sevaun Palvetzian, CEO of CivicAction. -

One Toronto Final Leaflet

WARD NAME/NUMBER COUNCILLOR PHONE EMAIL Mayor Rob Ford 416-397-2489 [email protected] 1 Etobicoke North Vincent Crisan3 416-392-0205 [email protected] 2 Etobicoke North Doug ForD 416-397-9255 [email protected] 3 Etobicoke Centre Doug HolyDay 416-392-4002 [email protected] 4 Etobicoke Centre Gloria LinDsay Luby 416-392-1369 [email protected] 5 Etobicoke-Lakeshore Peter Milczyn 416-392-4040 [email protected] 6 Etobicoke-Lakeshore Mark Grimes 416-397-9273 [email protected] Have your say: What Kind Of Toronto Do You Want? 7 York West Giorgio Mammoli3 416-395-6401 [email protected] 8 York West Anthony Perruzza 416-338-5335 [email protected] 9 York Centre Maria Augimeri 416-392-4021 [email protected] A People’s Guide to the Toronto Service Review 10 York Centre James Pasternak 416-392-1371 [email protected] 11 York South-Weston Frances Nunziata 416-392-4091 [email protected] 12 York South-Weston Frank Di Giorgio 416-392-4066 [email protected] 13 ParkDale-High Park Sarah DouceVe 416-392-4072 [email protected] City Hall has launched a public consultation process, called the Toronto 14 ParkDale-High Park GorD Perks 416-392-7919 [email protected] Service Review. Let’s send a strong signal to our City Councillors and the 15 Eglinton-Lawrence Josh Colle 416-392-4027 [email protected] 16 Eglinton-Lawrence Karen S3ntz 416-392-4090 [email protected] Mayor about the kind of Toronto we want to live in and pass on to our 17 Davenport Cesar Palacio 416-392-7011 [email protected] children. -

In Toronto Ward Races, Most Incumbents Rule October 23Rd, 2014 Tory Has Lead for Mayor in Most Wards

MEDIA INQUIRIES: Lorne Bozinoff, President [email protected] 416.960.9603 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TORONTO In Toronto Ward races, most incumbents rule October 23rd, 2014 Tory has lead for mayor in most wards TORONTO October 23rd, 2014 - In a series of samplings of publIc opinion across most HIGHLIGHTS: of Toronto's wards taken by the Forum Poll™ In the days leadIng up to the municIpal electIon among voters In each ward, It appears Incumbents have the upper hand • In the days leading up to the where they are runnIng. FIndIngs are reported below on a ward-by-ward basIs. Note munIcIpal electIon among that some sample sIzes for wards are small, and analysIs of sub-groups calls for voters In each ward, It cautIon. appears Incumbents have the Ward 1, Etobicoke North - Ford, Crisanti lead upper hand where they are Among the 139 voters polled In Ward 1, Incumbent Vincent CrIsantI has the lead for runnIng. councillor (51%) and no other candIdate of the 12 lIsted gets even double dIgIts. One • In Ward 1, Incumbent fifth are undecIded (19%). Doug Ford has a clear advantage In thIs ward (65%), Vincent CrIsantI has the lead compared to John Tory (22%) and, especially, OlIvia Chow (6%). for councIllor (51%) and no Ward 2, Etobicoke North - Ford and Ford Forever other candidate of the 12 listed gets even double digits. Mayor Rob Ford has the lead for councIllor among the 216 voters polled In thIs ward (45%), and Is only challenged, In equal measure, by Andray DomIse (15%) and • In Ward 2, Mayor Rob Ford MunIra Abukar (14%). -

Previously Approved Child Care Projects Impacted by Ford Government Cuts to Child Care Funding

Previously approved child care projects impacted by Ford government cuts to child care funding Ward, riding, Councillor, Estimated MPP Board Project / School Address Infants Toddlers Preschoolers Total Occupancy date Ward 1, Etobicoke North, Councillor Michael Ford, MPP Doug Ford 1 TDSB Elmbank JMA 10 Pittsboro Dr 10 30 48 88 2022 Q3 1 TDSB Kingsview Village JS 1 York Rd 10 30 48 88 2022 Q3 1 TCDSB St John Vianney 105 Thistle Down Blvd 10 15 24 49 2020 Q3 Total Ward 1 3 Sites 30 75 120 225 Ward 2, Etobicoke Centre, Councillor Stephen Holyday, MPP Kinga Surma 2 CSV ÉÉP Felix Leclerc 50 Celestine Dr 10 15 24 49 TBD 2 TCDSB Father Serra CS 111 Sun Row Dr 10 15 24 49 TBD 2 TDSB Dixon Grove JMS 315 The Westway 10 30 48 88 2022 Q3 2 TDSB Valleyfield JS 35 Saskatoon Dr 10 30 48 88 2022 Q3 2 TCDSB Nativity of Our Lord 35 Saffron Crescent 10 30 48 88 2021 Q4 Total Ward 2 5 Sites 50 120 192 362 Ward 4, Parkdale - High Park, Councillor Gord Perks, MPP Bhutila Karpoche 4 TCDSB Holy Family 141 Close Avenue 10 15 24 49 2020 Q3 Total Ward 4 1 Site 10 15 24 49 Ward 5, York South Weston, Councillor Councillor Frances Nunziata, MPP Faisal Hassan 5 CSV ÉÉP Mathieu da Costa 116 Cornelius Pkwy 10 15 24 49 TBD 5 TCDSB St Bernard CS 12 Duckworth St 10 15 24 49 2021 Q3 5 TCDSB Santa Maria CS 25 Avon Ave 0 15 24 39 2021 Q1 5 TDSB Weston Memorial JPS 200 John St 10 15 24 49 2022 Q3 5 TDSB Pelmo Park PS 180 Gary Dr 10 15 24 49 2019 Q4 5 TDSB Bala Avenue PS 6 Bala Ave 10 15 24 49 2021 Q3 Total Ward 5 6 Sites 50 90 144 284 Ward 7, Humber River - Black Creek, Councillor