The Weirdest Mayoralty Ever—The Inside Story Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nancy Marshau- Ward 22 Library Cuts To: Date: Subject: John Warren

Page 1oft Nancy MarshaU- Ward 22 Library Cuts From: John Warren <[email protected]> To: <nmarshall@torontopubliclibrary .ca> Date: October 18, 2011 9:40PM Subject: Ward 22 Library Cuts Dear Ms. Marshall, I am a frequent user of The Deer Park Branch and there is no reason that I can see that it is underutilized at any time during the day and week. The adults are the prime users and the computers all always busy, the media area it is hard to find a chair most times, there are people amongst the stacks and DVD shelves. I am a writer, amongst other things, and order many books that I pick up there. There are many more reasons that I could mention but I think you get my point that these cuts are not investigated adequately and rationally thought out I see that 39 branches will be up for cuts and interestingly, so I read, many are in the poorer areas and the most busy! This is FORD's logical ill-logic. Thank you for hearing my feedback. Good luck and Best Regards, John Warren #22 - 494 Avenue Rd M4V2J5 file://C:\Documents and Settings\nmarshall\Local Settings\Temp\XPgrpwise\4E9DF233... 21110/2011 Proposed Ltbrary reducttons ~LtPage I of! Nancy MarshaU- Proposed Library reductions From: Iori harrison <[email protected]> To: <[email protected]> Date: October 18,2011 9:51PM Subject: Proposed Library reductions Hello, I would like to voice my concerns about cutting library times. libraries are a fundamental core service for our communities that service young people, new Canadians, the elder1y and everyone in between. -

George Street Revitalization Recommended Scope and Approach

Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 3, 2015 with amendments. This item was considered by the Executive Committee on October 20, 2015 and adopted without amendment. It will be considered by City Council on November 3, 2015. City Council consideration on November 3, 2015 EX9.6 ACTION Amended Ward:All George Street Revitalization Recommended Scope and Approach City Council Decision City Council on November 3 and 4, 2015, adopted the following: 1. City Council endorse the project scope for the George Street Revitalization as outlined in Attachment 1 to the report (October 5, 2015) from the Deputy City Manager, Cluster A and the Deputy City Manager and Chief Financial Officer, and the Seaton House transition plan Option Two as outlined in Attachment 3 to the report (October 5, 2015) from the Deputy City Manager, Cluster A and the Deputy City Manager and Chief Financial Officer, and forward Attachments 1 and 3 to the City Manager for consideration with other City priorities as part of the 2016 budget process. 2. City Council authorize the Chief Corporate Officer to retain procurement option consultants at an estimated cost of $100,000 (net of all taxes and charges) to conduct an analysis of project procurement and delivery options. 3. City Council direct the Chief Corporate Officer to report back by June 2016 on the recommended delivery model, the implementation funding needed and the resulting refined capital cost estimates for the George Street Revitalization as outlined in Attachment 1 and the Seaton House transition plan Option Two as outlined in Attachment 3 to the report (October 5, 2015) from the Deputy City Manager, Cluster A and the Deputy City Manager and Chief Financial Officer. -

ONTARIO HYDRO CA9301039 Nf — 13/73

ONTARIO HYDRO CA9301039 n f — 13/73 rT m *rr! w~ LET'S GIVE TOMORROW A HAND serves the people of Ontario by supplying reliable electricity services at a competitive price. It provides consumers with information and programs on the wise use of energy and offers customers financial incentives to invest in energy efficient technology. Ontario Hydro has assets of more than S4.i billion, making it one of the largest public utilities in North America. 1 he Corporation employs more than _;.Odd regular and approximately 6.01)0 part-time and temporary staff. Created in M>f> by special provincial statute. Ontario Hydro operates under the Power Corporation Act to deliver electricity throughout Ontario. It also produces and sells steam and hot water as primary products. It regulates Ontario's municipal utilities and. in co-operation with the Canadian Standards Association, is responsible for the inspection and approval of electrical equipment and wiring throughout the province. Ontario Hydro operates 31 hydroelectric, nuclear and fossil-fuelled generating stations as well as a transmis- sion system that distributes power to customers across the province. The Corporation supplies electricity directly to about ^25.000 rural retail customers. It also sells power to .^1 I municipal utilities serving 2.2 million Ontario customers, and provides electricity directly to almost 110 large industrial customers with load requirements in excess of five megawatts. Ontario Hydro is a financially self-sustaining corporation without share capital. Bonds and notes issued by Hydro are guaranteed by the Province of Ontario. The Corporation is governed by a Board of Directors, consisting of up to 1" members. -

Embracing Pregnancy with a Doula Toronto, and Queen’S Park

ww The East York SPIKE IN VIOLENCE n Week of crime OBSERVER Page 2 Serving our community since 1972 Vol. 44, No. 3 www.torontoobserver.ca Friday, March 6, 2015 E.Y.’s former mayor heads ‘south’ By MATT GREEN The Observer He may have lost the June provincial election by a percentage point, but former MPP Mi- chael Prue was feeling the love from East Yorkers on Feb. 26. Prue, whose political career in East York lasted more than a Photo courtesy of Vince Berns/East Side Players quarter-century, was Curtain closing the man of the hour at the “Michael Prue There’s still time — but not much — to see the East Side Players’ latest production, Speaking in Tongues. The Observer’s Appreciation Night,” Chris DeMelo praises the acting in his review, on page 8. The cast includes (l-r) Kizzy Kaye, Ted Powers, Steve Switzman which took place at the and Lydia Kiselyk. Speaking in Tongues plays again tonight but concludes its run tomorrow, March 7, in the Papermill The- Palace restaurant on atre at Todmorden Mills Heritage Site on Pottery Road. Pape Avenue. About 120 people n CHILDBIRTH gathered to celebrate Prue’s years of public service within the former Borough of East York, the “megacity” of Embracing pregnancy with a doula Toronto, and Queen’s Park. It was a last hur- gested using a doula as well. rah in more ways than Doulas provide clinical support “They said their doulas had been very supportive one… because Prue and the ‘personal touch of family’ during their labour process,” McKane said, and after and his wife Shirley are doing some research, that’s the route she decided to preparing to move 400 By STEPHANIE BACKUS take. -

Debates of the Senate

Debates of the Senate 2nd SESSION . 41st PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 149 . NUMBER 26 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, December 11, 2013 The Honourable NOËL A. KINSELLA Speaker CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates Services: D'Arcy McPherson, National Press Building, Room 906, Tel. 613-995-5756 Publications Centre: David Reeves, National Press Building, Room 926, Tel. 613-947-0609 Published by the Senate Available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 722 THE SENATE Wednesday, December 11, 2013 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. practice their independent religion or who are wrongfully convicted, as happened to Mr. Ghassemi-Shall, endure torture to elicit information or confessions, and then trial by a so-called Prayers. ``judiciary'' with virtually no protection of the right to a fair process. VISITORS IN THE GALLERY According to the Iran Human Rights Documentation Centre, The Hon. the Speaker: Honourable senators, I wish to draw over 600 people have been executed in Iran in 2013. Three your attention to the presence in the gallery of Hamid Ghassemi- hundred of those have been sent to their deaths after President Shall and his spouse, Antonella Mega. They are guests of the Rouhani assumed office in August. Since Rouhani's Honourable Senator Frum. inauguration, the number of prisoners being sent to the gallows has accelerated, not decreased. On behalf of all honourable senators, I welcome you to the Senate of Canada. It was during a visit to his mother in 2008 that Hamid Ghassemi-Shall was caught up in an Orwellian nightmare while Hon. -

TEA Leaves 2009

the newsletter of the toronto environmental alliance ISSUE 01, VOLUME 09 Award winning musician and activist Sarah Harmer joins TEA campaigner Jamie Kirkpatrick to launch “Dig Conservation, Not Holes” in April 2009. Photo by Michael Stuparyk, Toronto Star INSIDE Key Victories • Campaign Updates • Environmental Midterm Report Card • Toronto’s Big Pit • Greenbelt in Toronto • The TEA Team • Funders the newsletter of the toronto environmental alliance ISSUE 01, VOLUME 09 INSIDE Victory at City Hall! Campaign Updates 2 TORONTO FINALLY GETS THE RIGHT Report Card 5 TO KNOW WHO IS POLLUTING Toronto’s Big Pit 6 After almost 5 years of campaigning and thanks to massive community support, Torontonians now have the “right to know” who is polluting Council Grades 9 their neighbourhood. Greenbelt 10 On December 3rd, Toronto City Council voted for a precedent-setting toxics disclosure policy. With an overwhelming vote of 33-3, Toronto The TEA Team 11 became the first city to require that businesses - including dry cleaners, Funders 11 funeral homes, and auto-body repair shops - reveal their discharges of 25 priority substances that pollute Toronto’s air. Toronto residents should be proud: with your ongoing support we have paved the way for other cities across Canada to initiate and adopt similar bylaws – we all have a right to know! See page 2 for more information on how the bylaw will be implemented. with your ongoing support we have paved the way for other cities across canada to initiate and adopt similar bylaws LOCAL FOOD NOW ON THE CITY'S MENU In late October, Toronto became the first municipality in Canada to adopt a local food procurement policy with a target of purchasing 50% local food as soon as possible. -

Summary by Quartile.Xlsx

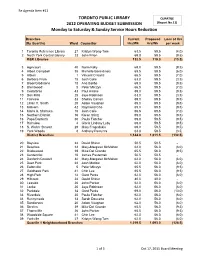

Re Agenda Item #11 TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY QUARTILE 2012 OPERATING BUDGET SUBMISSION (Report No.11) Monday to Saturday & Sunday Service Hours Reduction Branches Current Proposed Loss of Hrs (By Quartile) Ward Councillor Hrs/Wk Hrs/Wk per week 1 Toronto Reference Library 27 Kristyn Wong-Tam 63.5 59.5 (4.0) 2 North York Central Library 23 John Filion 69.0 59.5 (9.5) R&R Libraries 132.5 119.0 (13.5) 3 Agincourt 40 Norm Kelly 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 4 Albert Campbell 35 Michelle Berardinetti 65.5 59.5 (6.0) 5 Albion 1 Vincent Crisanti 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 6 Barbara Frum 15 Josh Colle 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 7 Bloor/Gladstone 18 Ana Bailão 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 8 Brentwood 5 Peter Milczyn 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 9 Cedarbrae 43 Paul Ainslie 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 10 Don Mills 25 Jaye Robinson 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 11 Fairview 33 Shelley Carroll 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 12 Lillian H. Smith 20 Adam Vaughan 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 13 Malvern 42 Raymond Cho 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 14 Maria A. Shchuka 15 Josh Colle 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 15 Northern District 16 Karen Stintz 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 16 Pape/Danforth 30 Paula Fletcher 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 17 Richview 4 Gloria Lindsay Luby 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 18 S. Walter Stewart 29 Mary Fragedakis 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 19 York Woods 8 AAnthonynthony Perruzza 63.0 59.5 ((3.5)3.5) District Branches 1,144.0 1,011.5 (132.5) 20 Bayview 24 David Shiner 50.5 50.5 - 21 Beaches 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 22 Bridlewood 39 Mike Del Grande 65.5 56.0 (9.5) 23 Centennial 10 James Pasternak 50.5 50.5 - 24 Danforth/Coxwell 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 25 Deer Park 22 Josh Matlow 62.0 56.0 (6.0) -

Framework Planning

PORT LANDS PLANNING FRAMEWORK Purpose / Elements of the Planning Framework The Purpose of the Port Lands Planning Framework is to: Elements of the Planning Framework: • Integrate the other planning initiatives currently underway • An overall vision for the Port Lands and development objectives • A connections plan which will identify: • Update and refresh the vision for the Port Lands o Major and intermediate streets o Major pedestrian and cycling facilities • Provide a comprehensive picture of how the area should redevelop over the long-term and o A transit plan that also addresses City Council direction reconcile competing interests • Generalized land use direction • Provide a flexible/adaptable planning regime • Identification of character areas • A parks and open space plan which will define: • Ensure sustainable community building o Green corridors o District / Regional parks • Ensure that public and private investments contribute to the long-term vision and have o Water’s Edge Promenades lasting value • A heritage inventory and direction for listing/designating heritage resources • Provide the basis for Official Plan amendments • Urban design principles and structure plan: o Built form and building typologies • Resolve Ontario Municipal Board appeals of the Central Waterfront Secondary Plan o Special sites (catalyst uses) o Relationship of development to major public spaces o Urban design context for heritage features o Identification of major views • A high -level community services and facilities strategy • Implementation and phasing direction PROCESS WE ARE HERE PHASE 2: PHASE 1: PHASE 3: Vision / Background Recommendations Alternatives CONSULTATION Public Meeting | November 28, 2013 PORT LANDS PLANNING FRAMEWORK Port Lands Acceleration Initiative Plan (PLAI) EASTER N AV.E DON VALLEY PARKWAY EASTERN AVENUE Don River DON RIVER NOD RI REV STREET LESLIE KRAP LAKE SHORE BOULEVARD EAST Port Lands Acceleration Initiative (PLAI) TRLYA DRS The PLAI was initiated in October 2011 to: New River Crossing DON ROADWAY CARLAW AVE. -

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 13, 2013 with amendments. City Council consideration on November 13, 2013 MM41.25 ACTION Amended Ward:All Requesting Mayor Ford to respond to recent events - by Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, seconded by Councillor Peter Milczyn City Council Decision Caution: This is a preliminary decision. This decision should not be considered final until the meeting is complete and the City Clerk has confirmed the decisions for this meeting. City Council on November 13 and 14, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for misleading the City of Toronto as to the existence of a video in which he appears to be involved in the use of drugs. 2. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to co-operate fully with the Toronto Police in their investigation of these matters by meeting with them in order to respond to questions arising from their investigation. 3. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for writing a letter of reference for Alexander "Sandro" Lisi, an alleged drug dealer, on City of Toronto Mayor letterhead. 4. City Council request Mayor Ford to answer to Members of Council on the aforementioned subjects directly and not through the media. 5. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to take a temporary leave of absence to address his personal issues, then return to lead the City in the capacity for which he was elected. 6. City Council request the Integrity Commissioner to report back to City Council on the concerns raised in Part 1 through 5 above in regard to the Councillors' Code of Conduct. -

Before Candidates in the June 12 Election Take A

Before candidates in the June 12th election take a seat, ask them to pull up a chair. Government policies affect the world our Education Day is a non-partisan event Riding: Etobicoke-Lakeshore children and youth will inherit tomorrow. where local candidates from the four Candidates: Peter Milczyn They affect their opportunities to get a major Provincial parties share their views Ontario Liberal Party good education today. The Provincial and answer questions on the issues Doug Holyday government decides what is taught in our affecting public education. Ontario PC Party schools and how much of our Provincial taxes are used to pay for education. The For a full summary of ridings, candidates P.C. Choo Ontario NDP future growth of the province depends on and the education platforms of the four high quality, publicly-funded education. major parties participating in the June 12 Angela Salewsky This affects you whether or not you have Provincial Election visit: www.opsba.org Ontario Green Party children in the school system. Moderator: Kate Hammer Etobicoke-Lakeshore Education Day is Reporter, The results of the upcoming Provincial coordinated by Toronto District School Globe and Mail election are far-reaching. As a voter and Board Trustee Pamela Gough. Location: Lambton Kingsway JMS citizen of Ontario it is in your interest to Follow the conversation on Twitter: 525 Prince Edward Dr. know where the candidates stand on the #oed14 Time: Tuesday May 27 issues. So get involved. @pamelagough at 7:30 – 9 pm MAY 27, 2014: EDUCATION DAY Before you make your X, know your candidates’ ABCs . -

Can Toronto Be Run Like a Business? Observations on the First Two Years of the Ford Mayoralty in Torontoi

Can Toronto be Run Like a Business? Observations on the First Two Years of the Ford Mayoralty in Torontoi. Richard Stren Cities Centre University of Toronto Prepared for Presentation at the CPSA Annual Conference, Edmonton, Alberta June, 2012 Draft Only. No Citations or References without Express Consent of the Author. Mayoral candidate Rob Ford’s speech at the National Ethnic Press and Media Council of Canada (August 9, 2010): I come from the private sector, where my father started a labeling company….I’m proud to say that with the help of my brothers we have expanded to three locations in New Jersey, Chicago and Rexdale, and we now employ approximately 300 people….What I have seen in the last ten years is very disturbing at City Hall. I’ve seen taxes go up and services go down… In the private sector, we deliver, it’s very simple. The first rule is, the customer is always right. The second rule is, repeat the first rule…In politics we should take the exact same attitude….The taxpayer is the boss of all the civil servants….I really take a business approach to politics…in that customer service is lacking at city hall. …Customer service is number one. Downloaded on May 10, 2012 at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOBotCHFRZE Video interview with Rob Ford on the day before the 2010 election: …[my brother and I have] run my father’s business that he started in 1962. We’ve expanded into Chicago and New Jersey. That’s the business approach I want to take to running the city. -

Back, Brick Works

THE EAST TORONTO INSIDEINSIDE Powerful Election Polaroids Preview PAGE 8 OBSERVER PAGES 3, 4, 5 Friday • October 1 • 2010 PUBLISHED BY CENTENNIAL COLLEGE JOURNALISM STUDENTS AND SERVING EAST YORK Volume 40 • No. 7 Mixed reviews as Kennedy rejoins school board fray By CHRIS HIGGINS guilty of conflict of interest is The race to represent Ward not a small matter.... This is just 11 on Toronto’s Catholic school outrageous that she would think board has heated up with the that she deserves a vote and to last-minute entry of former say she’s not running and to run trustee Angela Kennedy. again and then to put in the ap- In a dramatic reversal of her peal.” previous decision not to run, One of Kennedy’s rivals for Kennedy filed her candidacy pa- the Ward 11 trustee seat agrees. pers on deadline day, Sept. 10. Kevin Morrison says this is a Kennedy had been a trustee critical election for the TCDSB with the Toronto Catholic Dis- and Kennedy’s decision to run trict School Board for 10 years, could further erode public per- but was found to be in violation ceptions of the board’s credibil- of conflict-of-interest rules and ity. was removed as trustee by a “People are so incredibly an- court order in August. gry,” he said. “I have been can- Kennedy has children work- vassing in parishes that have Observer, Reinisa MacLeod ing for the TCDSB and the judge traditionally been strongholds FLAMBOYANT FEATHERS: Miranda Allen, a performer with Clay & Paper Theatre, dances on found she voted on budget mat- of Angela’s...