How the Facebook Usage Patterns of Toronto City Councilors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 TDSA City Councillors and Mpps– 2018 Yellow – Agency White – TDSA Agency City Councillor Information Based on Head Offi

TDSA City Councillors and MPPs– 2018 Yellow – Agency White – TDSA agency City Councillor Information based on head office (as of December 2018) Green – TDSA agency MPP information based on head office TEL: 416 449-9651 BOB RUMBALL CANADIAN CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR THE DEAF FAX: 416 380 3419 2395 Bayview Avenue, North YorK, ON M2L 1A2 Councillor Jaye Robinson – Ward 15 Don Valley West Toronto City Hall 100 Queen Street West, Suite A12 Toronto, ON M5H 2N2 Telephone: 416-395-6408 FaX: 416-395-6439 Email: [email protected] Don Valley West Queen's Park Constituency Electoral District Number 022 Room 420 Suite 101 Main Legislative building, 795 Eglinton Avenue East Member of Provincial Queen's Park Toronto Parliament Toronto Ontario Kathleen O. Wynne Ontario M4G 4E4 [email protected] M7A 1A8 Tel 416-425-6777 Tel 416-325-4705 FaX 416-425-0350 FaX 416-325-4726 Date Agency Attended City Councillor/MPP office: TEL: 416 245-5565 CORBROOK FAX; 416 245-5358 581 Trethewey Drive, Toronto, Ont. M6M 4B8 Councillor Frances Nunziata – Ward 5 York South-Weston Toronto City Hall 100 Queen Street West, Suite C49 Toronto, ON M5H 2N2 Telephone: 416-392-4091 FaX: 416-392-4118 Email: [email protected] 1 York South—Weston Queen's Park Constituency Electoral District Number 122 Room 112 99 Ingram Drive Main Legislative building, Toronto Member of Provincial Queen's Park Ontario Parliament Toronto M6M 2L7 Faisal Hassan Ontario Tel 416-243-7984 [email protected] M7A 1A5 FaX 416-243-0327 Tel 416-326-6961 FaX 416-326-6957 Date Agency Attended City Councillor/MPP office: TEL: 416 340-7929 CORE FAX: 416 340-8022 160 SpringhurSt Ave., Suite 300, Toronto, Ont. -

Member Motion City Council MM9.11

Member Motion City Council Motion Without Notice MM9.11 ACTION Ward: 8 Ontario Municipal Board Hearing – Committee of Adjustment Application – 3965 Keele Street - by Councillor Anthony Perruzza, seconded by Councillor Frank Di Giorgio * This Motion has been deemed urgent by the Chair. * This Motion is not subject to a vote to waive referral. * This Motion has been added to the agenda and is before Council for debate. Recommendations Councillor Anthony Perruzza, seconded by Councillor Frank Di Giorgio recommends that: 1. City Council authorize the City Solicitor, appropriate Planning staff and any other City representation as required to attend the Ontario Municipal Board hearing to uphold the Committee of Adjustment’s decision. Summary The Toronto Transit Commission submitted a Minor Variance application to the North York Panel of the Committee of Adjustment to permit the development of a bus terminal associated with the Finch West Subway Station on Toronto-York Spadina Subway Extension. Variances were requested to former City of North York Zoning By-law No. 7625 with respect to a reduced front yard setback and reduced front yard landscaping requirements. City Planning staff have been working with the TTC on the design of this facility for two years and had no objections to the requested variances. The Committee of Adjustment for the City of Toronto (North York Panel) approved the Minor Variance application at its April 28, 2011 meeting. Metro Toronto Condominium Corporation 863, the Condominium Corporation for 1280 Finch Avenue West (east of the proposed bus terminal), has appealed the decision of the Committee of Adjustment to the Ontario Municipal Board. -

Summary by Quartile.Xlsx

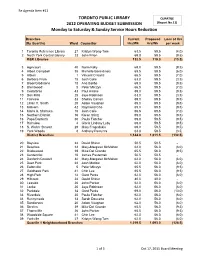

Re Agenda Item #11 TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY QUARTILE 2012 OPERATING BUDGET SUBMISSION (Report No.11) Monday to Saturday & Sunday Service Hours Reduction Branches Current Proposed Loss of Hrs (By Quartile) Ward Councillor Hrs/Wk Hrs/Wk per week 1 Toronto Reference Library 27 Kristyn Wong-Tam 63.5 59.5 (4.0) 2 North York Central Library 23 John Filion 69.0 59.5 (9.5) R&R Libraries 132.5 119.0 (13.5) 3 Agincourt 40 Norm Kelly 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 4 Albert Campbell 35 Michelle Berardinetti 65.5 59.5 (6.0) 5 Albion 1 Vincent Crisanti 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 6 Barbara Frum 15 Josh Colle 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 7 Bloor/Gladstone 18 Ana Bailão 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 8 Brentwood 5 Peter Milczyn 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 9 Cedarbrae 43 Paul Ainslie 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 10 Don Mills 25 Jaye Robinson 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 11 Fairview 33 Shelley Carroll 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 12 Lillian H. Smith 20 Adam Vaughan 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 13 Malvern 42 Raymond Cho 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 14 Maria A. Shchuka 15 Josh Colle 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 15 Northern District 16 Karen Stintz 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 16 Pape/Danforth 30 Paula Fletcher 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 17 Richview 4 Gloria Lindsay Luby 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 18 S. Walter Stewart 29 Mary Fragedakis 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 19 York Woods 8 AAnthonynthony Perruzza 63.0 59.5 ((3.5)3.5) District Branches 1,144.0 1,011.5 (132.5) 20 Bayview 24 David Shiner 50.5 50.5 - 21 Beaches 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 22 Bridlewood 39 Mike Del Grande 65.5 56.0 (9.5) 23 Centennial 10 James Pasternak 50.5 50.5 - 24 Danforth/Coxwell 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 25 Deer Park 22 Josh Matlow 62.0 56.0 (6.0) -

While Every Effort Is Made to Ensure the Accuracy of the Contents

While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the contents of this site, users should be aware that due to circumstances beyond our control, it may be necessary to change the text of documents posted here and therefore no responsibility will be accepted by the Toronto Transit Commission for discrepancies which may occur between documents contained on this site and the formal hardcopy versions presented to the Commission. If it is necessary to rely on the accuracy of Commission documents the Office of the General Secretary should be contacted at 393-3698 to obtain a certifed copy. ONLY HARDCOPY RECORDS CERTIFIED BY THE GENERAL SECRETARY WILL BE DEEMED TO BE OFFICIAL. Form Revised: February 2005 TORONTO TRANSIT COMMISSION REPORT NO. MEETING DATE: March 21, 2007 SUBJECT: Membership – TTC Committees RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Commission receive this report for information. DISCUSSION The attached provides a list of TTC Committees along with the membership for each Committee. - - - - - - - - - - - - March 2, 2007 1-16 Attachment TTC COMMITTEES TTC PROPERTY COMMITTEE Michael Thompson (Chair) Glenn De Baeremaeker Adam Giambrone Suzan Hall Peter Milczyn Anthony Perruzza TTC ADVERTISING REVIEW COMMITTEE Sandra Bussin Suzan Hall Anthony Perruzza Bill Saundercook (Committee Chair to be determined) TTC AUDIT COMMITTEE Bill Saundercook (Chair) Adam Giambrone Anthony Perruzza TTC BUDGET COMMITTEE Adam Giambrone Joe Mihevc Peter Milczyn Anthony Perruzza Bill Saundercook Michael Thompson (Committee Chair to be determined) TTC e-SYSTEM -

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 13, 2013 with amendments. City Council consideration on November 13, 2013 MM41.25 ACTION Amended Ward:All Requesting Mayor Ford to respond to recent events - by Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, seconded by Councillor Peter Milczyn City Council Decision Caution: This is a preliminary decision. This decision should not be considered final until the meeting is complete and the City Clerk has confirmed the decisions for this meeting. City Council on November 13 and 14, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for misleading the City of Toronto as to the existence of a video in which he appears to be involved in the use of drugs. 2. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to co-operate fully with the Toronto Police in their investigation of these matters by meeting with them in order to respond to questions arising from their investigation. 3. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for writing a letter of reference for Alexander "Sandro" Lisi, an alleged drug dealer, on City of Toronto Mayor letterhead. 4. City Council request Mayor Ford to answer to Members of Council on the aforementioned subjects directly and not through the media. 5. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to take a temporary leave of absence to address his personal issues, then return to lead the City in the capacity for which he was elected. 6. City Council request the Integrity Commissioner to report back to City Council on the concerns raised in Part 1 through 5 above in regard to the Councillors' Code of Conduct. -

Can Toronto Be Run Like a Business? Observations on the First Two Years of the Ford Mayoralty in Torontoi

Can Toronto be Run Like a Business? Observations on the First Two Years of the Ford Mayoralty in Torontoi. Richard Stren Cities Centre University of Toronto Prepared for Presentation at the CPSA Annual Conference, Edmonton, Alberta June, 2012 Draft Only. No Citations or References without Express Consent of the Author. Mayoral candidate Rob Ford’s speech at the National Ethnic Press and Media Council of Canada (August 9, 2010): I come from the private sector, where my father started a labeling company….I’m proud to say that with the help of my brothers we have expanded to three locations in New Jersey, Chicago and Rexdale, and we now employ approximately 300 people….What I have seen in the last ten years is very disturbing at City Hall. I’ve seen taxes go up and services go down… In the private sector, we deliver, it’s very simple. The first rule is, the customer is always right. The second rule is, repeat the first rule…In politics we should take the exact same attitude….The taxpayer is the boss of all the civil servants….I really take a business approach to politics…in that customer service is lacking at city hall. …Customer service is number one. Downloaded on May 10, 2012 at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOBotCHFRZE Video interview with Rob Ford on the day before the 2010 election: …[my brother and I have] run my father’s business that he started in 1962. We’ve expanded into Chicago and New Jersey. That’s the business approach I want to take to running the city. -

Toronto City Council Enviro Report Card 2010-2014

TORONTO CITY COUNCIL ENVIRO REPORT CARD 2010-2014 TORONTO ENVIRONMENTAL ALLIANCE • JUNE 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY hortly after the 2010 municipal election, TEA released a report noting that a majority of elected SCouncillors had committed to building a greener city. We were right but not in the way we expected to be. Councillors showed their commitment by protecting important green programs and services from being cut and had to put building a greener city on hold. We had hoped the 2010-14 term of City Council would lead to significant advancement of 6 priority green actions TEA had outlined as crucial to building a greener city. Sadly, we’ve seen little - if any - advancement in these actions. This is because much of the last 4 years has been spent by a slim majority of Councillors defending existing environmental policies and services from being cut or eliminated by the Mayor and his supporters; programs such as Community Environment Days, TTC service and tree canopy maintenance. Only in rare instances was Council proactive. For example, taking the next steps to grow the Greenbelt into Toronto; calling for an environmental assessment of Line 9. This report card does not evaluate individual Council members on their collective inaction in meeting the 2010 priorities because it is almost impossible to objectively grade individual Council members on this. Rather, it evaluates Council members on how they voted on key environmental issues. The results are interesting: • Average Grade: C+ • The Mayor failed and had the worst score. • 17 Councillors got A+ • 16 Councillors got F • 9 Councillors got between A and D In the end, the 2010-14 Council term can be best described as a battle between those who wanted to preserve green programs and those who wanted to dismantle them. -

Remuneration Report Appendix and Attachments

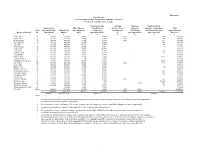

Attachment 1 City of Toronto Summary of Remuneration and Expenses for Members of Council For the year ended December 31, 2020 Expenses from the Corporate Expenses Expenses Paid by Remuneration Office Expenses Council General Business Travel Charged to Agencies, Corporations Total Ward and Benefits (See Support Staff (See Appendices Budget (See (See Appendix City Divisions and Other Bodies (See Remuneration and Member of Council No. Appendix A) Salaries B1, F) Appendices B2, F) C1) (See Appendix D) Appendix C2, E) Expenses $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ Ainslie, Paul 24 147,654 443,918 29,844 17,376 1,844 579 641,215 Bailão, Ana 9 143,254 481,178 13,930 52,703 1,667 349 693,081 Bradford, Brad 19 147,654 479,659 36,241 62,145 1,930 121 727,750 Carroll, Shelley 17 148,260 454,737 23,397 22,060 376 648,831 Colle, Mike 8 128,150 422,517 31,823 38,719 44 621,253 Crawford, Gary 20 147,654 449,990 21,304 18,601 3 637,552 Cressy, Joe 10 147,654 468,989 13,031 105,462 735,136 Filion, John 18 143,169 481,189 30,030 12,881 84 667,353 Fletcher, Paula 14 145,881 465,850 31,082 18,149 389 661,351 Ford, Michael 1 143,254 438,940 19,614 43,058 644,866 Grimes, Mark 3 147,654 427,231 17,748 22,052 5,342 620,027 Holyday, Stephen 2 147,654 303,412 198 13,591 464,855 Karygiannis, Jim (Note 9) 22 91,151 273,994 15,931 13,269 2,545 396,890 Lai, Cynthia 23 148,780 448,702 27,024 41,840 1,430 161 667,937 Layton, Mike 11 147,654 472,441 13,955 19,798 653,848 Matlow, Josh 12 147,654 482,000 17,795 35,742 95 683,286 McKelvie, Jennifer 25 150,979 433,588 26,612 49,358 660,537 Minnan-Wong, -

(In)Equity in Active Transportation Planning

(In)Equity in Active Transportation Planning: Toronto’s Overlooked Inner Suburbs by Mohammed Mohith Supervised by Professor Liette Gilbert A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada July 2019 Abstract Active transportation modes in North America are often accounted as ‘white strips of gentrification’ as advocacy for walking and bicycle infrastructure is characterized as a manifestation of privilege (Mirk, 2009). Such concerns usually arise from complex cultural, historical and political currents influencing urban politics and policies. Policies and investments make the urban amenities and facilities easier or harder to access and have a huge impact on the lives of the city’s population depending on their social and spatial status. Unequal distribution of transportation investments due to lack of fair access to participate in the planning process is not uncommon in Canadian cities -- and in almost all cases lead to inequality in mobility benefits. Decisions of transit infrastructure priorities in Toronto historically and politically tend to favour affluent and influential communities. The goals, preferences and strategies of active transportation planning for Toronto, therefore, is worth a critical discussion and engagement. If the benefits of active transportation investments are to be fairly distributed across the city and among all users, equity will have to be comprehensively addressed in the planning process. The goal of this research paper is to evaluate Toronto’s current initiatives in active transportation planning in terms of social and spatial equities and to bring forward discrepancies in practices to outline relevant strategic directions. -

Toronto Civic Employees' Union, Local

Toronto Civic Employees’ Union, Local 416 110 Laird Drive Toronto, ON M4G 3V3 Tel: 416-968-7721 Fax: 416-968-7829 www.local416.ca MEDIA RELEASE LOCAL 416 CUPE LOCAL 416 CELEBRATES A CENTURY OF QUALITY PUBLIC Affiliated with the Canadian Labour Congress and the SERVICE FOR TORONTO Labour Council of Toronto & York Region CUPE Local 416 kicks off 100th anniversary celebrations with flag raising ceremony at Toronto City Hall TORONTO, ON (October 20, 2017)--Toronto Civic Employees Union CUPE Local 416 (Local 416) kicked off celebrations in honour of the union’s 100th anniversary by raising their flag at Toronto City Hall early EDDIE MARICONDA Friday morning. President Friday’s formal flag raising ceremony is, in part, a nod to the inauguration of the union back in October 1917 MATT FIGLIANO when a group of Toronto employees and World War I veterans attended a mass meeting regarding Vice President controversy around the British flag. A group of street cleaners considered the issue to be so important they felt it necessary to walk off the job, officially establishing the Toronto Civic Employees Union, known today as Local 416. RON JOHNSON 2nd Vice President Local 416 President, Eddie Mariconda, Vice President, Matt Figliano, and several other members of the Local 416 Executive Board were formally congratulated Friday morning by Mayor John Tory and Councillor Paula Fletcher. They were also joined by Councillors Shelley Carroll, Janet Davis, Glenn De Baeremaeker, Jim JERRY DOBSON Karygiannis, Mike Layton, Cesar Palacio, Neethan Shan, and Kristyn Wong-Tam. Secretary-Treasurer “This weekend marks a milestone for Local 416,” says Mariconda, “We are celebrating a century of quality public service - provided by our hard working members - and of partnership with the City of Toronto. -

Experience 'We Will Get Through This': Canadians Honour Humboldt Broncos Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee Makes Progress On

Premier Kathleen Wynne Care and meets with Ethnic Media to opportunity for all: discuss the 2018 Budget Naheed Yaqubian Page 6 Page 8 PAGE ONE Vol. 02 No. 4 ǀ April 16-30, 2018 Newswww.pageonenews.ca Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee makes progress on shared priorities Page One News transformative change that we Inuvialuit Settlement Region; ‘We will get through OTTAWA-The Prime Minister, need to make a real difference a commitment to eliminate Justin Trudeau, participated in for Inuit, for the benefit of all tuberculosis across Inuit the Inuit-Crown Partnership Canadians,” Prime Minister Nunangat by 2030, and to reduce this’: Canadians honour Committee meeting to review Justin Trudeau said. active tuberculosis by at least progress made since the During the meeting, the 50 per cent by 2025; progress Committee was formed last year Prime Minister and Inuit leaders on an Inuit early learning and Humboldt Broncos and to discuss what actions need reflected on the important child care framework, which Page One News assistant commissioner said to be taken to advance our shared progress made to strengthen the would reflect the distinct needs HUMBOLDT, Sask.- it was too early to comment commitment to reconciliation. Inuit-Crown relationship and to and priorities of Inuit children Community came together to on the cause of the collision. “Today’s meeting with Inuit address key social, economic, and families; progress toward a mourn those killed and injured in “The RCMP is continuing leaders was productive and cultural, and environmental new Arctic Policy Framework, the Humboldt Broncos bus crash. its investigation, which will encouraging. -

Annual Report

ARNNUAL EPORT 2010 2010 ANNUAL REPORT Toronto Transit Commission As at December 31, 2010 Chair Vice-Chair Karen Stintz Peter Milczyn Commissioners Maria Vincent Frank Norm Denzil Cesar John Augimeri Crisanti Di Giorgio Kelly Minnan-Wong Palacio Parker Letter from the Chair Date: April, 2011 To: Mayor Rob Ford and Councillors of the City of Toronto It is my privilege to submit the 2010 Annual Report for the Toronto Transit Commission, my first since becoming Chair of the TTC. Work Safe-Home Safe There is nothing more important to the TTC than safety – the safety of its customers, as well as the safety of its employees. In 2010, the Work Safe-Home Safe program, a safety initiative designed to reduce workplace injuries at the TTC, continued with great success. Since the program began in 2008, we have seen a reduction in our lost-time injury rate of more than 28 per cent. The program relies on all employees to participate and lead this safety program. Committees made up of unionized employees work with management employees to identify risks, and remove workplace hazards. The program’s goal is to ensure every TTC employee leaves work in the same condition in which he or she arrived – healthy and injury-free. Customer Service In March 2010, as part of the TTC’s commitment to customer service excellence, the Commission approved the formation of an independent Customer Service Advisory Panel. The panel was Chaired by Mr. Steve O’Brien. Mr. O’Brien has 30 years experience in the hospitality industry, and is the General Manager of One King West Hotel and Residence in downtown Toronto.