(In)Equity in Active Transportation Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Item 6C - Mabellearts - Long Term Lease and Operating Agreement for Parts of Mabelle Park TCHC April 27, 2021 Board Meeting Report #: TCHC:2021-27 Attachment 2 Item

Item 6C - MABELLEarts - Long Term Lease and Operating Agreement for parts of Mabelle Park TCHC April 27, 2021 Board Meeting Report #: TCHC:2021-27 Attachment 2 Item MABELLEarts 6C VALUATION OF PROGRAMS AND CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS - TCHC:2021-27 and BACKGROUND AND HISTORY WORKING WITH TCH Executive Summary This document sets out the value proposition supporting MABELLEarts proposal to lease Mabelle Park - on which MABELLEarts will construct a community building, improve the park and run programming. Attachment In exchange for entering into the lease TCH receives: • Capital Investment on its land of approximately $2 million+ • A commitment to provide programming which we value at $500,000+ per year 2 In addition, TCH tenants and the community benefit from heightened safety of an animated park space and opportunities to connect, inspire and lead. There is no way to place a number on that value. We have demonstrated below our ability to raise and sustain the funds to complete the Project and operate programming. The lease and proposed project are the result of years of community consultation and enjoys the support of the Mayor and local City Councillor. The cost to TCH is intended to be neutral – with its current cost of maintaining the park being paid to MABELLEarts as a fee for carrying out maintenance duties in the park. TCH will complete its own risk analysis. However, any risk can be mitigated in the Lease. Effectively the downside to TCH is that the lease will default and it will acquire ownership of a better park. “It's kinda weird. This is the first neighbourhood where I walk down the street and everyone is saying hi to me. -

Cycling Safety: Shifting from an Individual to a Social Responsibility Model

Cycling Safety: Shifting from an Individual to a Social Responsibility Model Nancy Smith Lea A thesis subrnitted in conformity wR the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario lnstitute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto @ Copyright by Nancy Smith Lea, 2001 National Library Bibliothbque nationale ofCanada du Canada Aoquieit-el services MbJiographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemiettant P. la National Library of Canada to BiblioWque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or oeîî reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette dièse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fihn, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propndté du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thése. thesis nor substantial exûacts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celîe-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement. reproduits sans son pemiission. almmaîlnn. Cycling Satety: Shifting from an Indhrldual to a Social Reaponribillty Modal Malter of Arts, 2001 Sociology and ~qultyStudie8 in Education Ontario Inrtltute for *die8 in- ducati ion ot the University of Toronto ABSTRACT Two approaches to urban cycling safety were studied. In the irrdividual responsibility rnodel, the onus is on the individual for cycling safety. The social responsibiiii model takes a more coliecthrist approach as it argues for st~cturallyenabling distriûuted respansibility. -

A Community Benefits Policy Framework for Ontario

Boldly Progressive, Fiscally Balanced: A Community Benefits Policy Framework for Ontario Community Benefits Ontario March 2017 March 13, 2017 Who We Are This Community Benefits Framework for Ontario was developed collaBoratively through participants in the Community Benefits Ontario network, a Broad network of Ontario nonprofits, foundations, labour groups, community organizations, municipal representatives and social enterprise leaders. This brief is brought forward by the following: Colette Murphy, Executive Director, Atkinson Foundation Anne Gloger, Principal, East Scarborough Storefront Terry Cooke, President & CEO, Hamilton Community Foundation Howard Elliott, Chair, Hamilton RoundtaBle for Poverty Reduction Marc Arsenault, Stakeholder Relations, Ironworkers District Council of Ontario Mustafa ABdi, Community Organizer, Communities Organizing for ResponsiBle Development, LaBour Community Services Elizabeth McIsaac, President, Maytree Sandy Houston, President and CEO, Metcalf Foundation Cathy Taylor, Executive Director, Ontario Nonprofit Network John Cartwright, President, Toronto & York Region LaBour Council Rosemarie Powell, Executive Director, Toronto Community Benefits Network Anne Jamieson, Senior Manager, Toronto Enterprise Fund Anita Stellinga, Interim CEO, United Way of Peel Region Lorraine Goddard, CEO, United Way/Centraide Windsor-Essex County Daniele Zanotti, President and CEO, United Way Toronto & York Region 1 March 13, 2017 “Infrastructure projects such as the Eglinton Crosstown LRT can create benefits for communities that go beyond simply building the infrastructure needed. Through this agreement, people facing employment challenges will have the opportunity to acquire new skills and get good joBs in construction. We’re Building more than transit. We’re Building partnerships and pathways that are creating more opportunities for people to thrive in the economy.” - Premier Kathleen Wynne 1 December 7, 2016 Premier Wynne greets contractors and construction workers at the ground breaking of the first Eglinton Crosstown station. -

Toronto City Council: Gardiner East Debate Vote/Support PROJECTION Based on Public Statements/Voting History

Toronto City Council: Gardiner East Debate Vote/Support PROJECTION Based on public statements/voting history. Subject to change. And then change again. For novelty purposes only. Got a tip or correction? Email [email protected] or get me at @GraphicMatt. 2015-06-10 Preferred option for Gardiner Expressway Team Tory Member of Council Notes between Jarvis St. and Percentage Don Valley Parkway PROJECTION Dec 2014 - May 2015 John Tory Maintain/Modify 100.00% Publicly stated his support 01 Mayor of Toronto Stephen Holyday Maintain/Modify 100.00% Officially endorsed "hybrid." 02 Ward 3 Etobicoke Centre Norman Kelly Maintain/Modify 100.00% Not 100% confirmed but supported maintaining Leslie stub in 03 Ward 40 Scarborough-Agincourt 1999. Likely Maintain/Modify. Denzil Minnan-Wong Maintain/Modify 100.00% 100% Maintain/Modify. Supported removing east-of-DVP spur in 04 Ward 34 Don Valley East 1999. Frances Nunziata Maintain/Modify 100.00% Publicly announced her support on June 3. Supported removing 05 Ward 11 York South-Weston east-of-DVP spur in 1999. Jaye Robinson Maintain/Modify 100.00% Publicly announced her support on June 4 06 Ward 25 Don Valley West Gary Crawford Maintain/Modify 94.74% Publicly announced support for Maintain on June 2 07 Ward 36 Scarborough Southwest Christin Carmichael Greb Maintain/Modify 94.44% Support for Maintain/Modify here: http://carmichaelgreb.com/can- 08 Ward 16 Eglinton-Lawrence toronto-afford-to-remove-the-gardiner-expressway-east/ James Pasternak Maintain/Modify 93.33% Has talked about tolling non-residents to pay for Maintain/Modify 09 Ward 10 York Centre option. -

Summary by Quartile.Xlsx

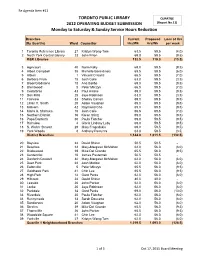

Re Agenda Item #11 TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY QUARTILE 2012 OPERATING BUDGET SUBMISSION (Report No.11) Monday to Saturday & Sunday Service Hours Reduction Branches Current Proposed Loss of Hrs (By Quartile) Ward Councillor Hrs/Wk Hrs/Wk per week 1 Toronto Reference Library 27 Kristyn Wong-Tam 63.5 59.5 (4.0) 2 North York Central Library 23 John Filion 69.0 59.5 (9.5) R&R Libraries 132.5 119.0 (13.5) 3 Agincourt 40 Norm Kelly 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 4 Albert Campbell 35 Michelle Berardinetti 65.5 59.5 (6.0) 5 Albion 1 Vincent Crisanti 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 6 Barbara Frum 15 Josh Colle 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 7 Bloor/Gladstone 18 Ana Bailão 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 8 Brentwood 5 Peter Milczyn 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 9 Cedarbrae 43 Paul Ainslie 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 10 Don Mills 25 Jaye Robinson 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 11 Fairview 33 Shelley Carroll 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 12 Lillian H. Smith 20 Adam Vaughan 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 13 Malvern 42 Raymond Cho 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 14 Maria A. Shchuka 15 Josh Colle 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 15 Northern District 16 Karen Stintz 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 16 Pape/Danforth 30 Paula Fletcher 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 17 Richview 4 Gloria Lindsay Luby 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 18 S. Walter Stewart 29 Mary Fragedakis 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 19 York Woods 8 AAnthonynthony Perruzza 63.0 59.5 ((3.5)3.5) District Branches 1,144.0 1,011.5 (132.5) 20 Bayview 24 David Shiner 50.5 50.5 - 21 Beaches 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 22 Bridlewood 39 Mike Del Grande 65.5 56.0 (9.5) 23 Centennial 10 James Pasternak 50.5 50.5 - 24 Danforth/Coxwell 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 25 Deer Park 22 Josh Matlow 62.0 56.0 (6.0) -

Cycle Toronto 2017 Candidate Profiles

Adam Tanel Ward - 29 Occupation - Lawyer Cyclist - Daily commuter and wannabe triathlete. Bio I am mildly obsessed with cycling, our city, and my dog Elvis. I am a lawyer who represents cyclists injured as a result of motorist negligence and/or inadequate cycling infrastructure. Find out more at: bikelawyers.ca Why I want to Join the Board I want to work with CycleTO to make cycling safer and more accessible. As a result of my day job, I am all too familiar with the carnage on Toronto’s streets. In 2014, this concern led me to run for City Council. My campaign team developed a robust cycling policy that greatly exceeded the "minimum grid" pledge. My policy platform called for more new cycling infrastructure than any other candidate running in 2014. Skills & experience I am familiar with the legal landscape, and how the law can be used as a tool to make cycling safer. I am on good terms with many of the important voices at City Hall. I have experience in law, politics, marketing, fundraising and NGO Boards. Adrian Currie Ward - 18 Occupation - Cycling Advocate, Actor & Film Maker Cyclist - Daily commuter Bio I am a Cycling Advocate, Actor & Film Maker who was born in Jamaica but grew up in Toronto. I have a BA in Economics and a BA in History both from McGill University. I presently sit on the Cycle Toronto Advocacy Committee and I am one of the co-chairs of the newly formed, Bicycle Parking Working Group. I am also a board member of the Community Bicycle Network and I am a past chair. -

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 13, 2013 with amendments. City Council consideration on November 13, 2013 MM41.25 ACTION Amended Ward:All Requesting Mayor Ford to respond to recent events - by Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, seconded by Councillor Peter Milczyn City Council Decision Caution: This is a preliminary decision. This decision should not be considered final until the meeting is complete and the City Clerk has confirmed the decisions for this meeting. City Council on November 13 and 14, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for misleading the City of Toronto as to the existence of a video in which he appears to be involved in the use of drugs. 2. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to co-operate fully with the Toronto Police in their investigation of these matters by meeting with them in order to respond to questions arising from their investigation. 3. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for writing a letter of reference for Alexander "Sandro" Lisi, an alleged drug dealer, on City of Toronto Mayor letterhead. 4. City Council request Mayor Ford to answer to Members of Council on the aforementioned subjects directly and not through the media. 5. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to take a temporary leave of absence to address his personal issues, then return to lead the City in the capacity for which he was elected. 6. City Council request the Integrity Commissioner to report back to City Council on the concerns raised in Part 1 through 5 above in regard to the Councillors' Code of Conduct. -

TORONTO CITY COUNCIL ORDER PAPER Meeting 8 Thursday, July 9

TORONTO CITY COUNCIL ORDER PAPER Meeting 8 Thursday, July 9, 2015 Total Items: 42 TODAY’S BUSINESS 9:30 a.m. Call to Order Council will review and adopt the Order Paper* 12:30 p.m. Council will recess 2:00 p.m. Council will reconvene Members of Council can release holds on Agenda Items Prior to 8:00 p.m. Members of Council can release holds on Agenda Items Council will enact General Bills Council will enact a Confirming Bill 8:00 p.m. Council will recess 2 Civic Appointments Committee - Meeting 9 CA9.2 Appointment of Member to the Toronto Police Services Board (Ward All) Held Communications CA9.2.1 to CA9.2.3 have been submitted on this Councillor Item. Michael Thompson Confidential Attachment - Personal matters about identifiable individuals who are being considered for appointment to the Toronto Police Services Board Community Development and Recreation Committee - Meeting 5 CD5.3 Extension of the Toronto Fire Services and Centennial College Program to Promote Increased Student Diversity in Pre-Service Held Firefighter Training (Ward All) Councillor James The Fire Chief and General Manager, Fire Services has submitted a Pasternak supplementary report on this Item (CD5.3a for information) CD5.9 Child Care Funding Strategy (Ward All) Held The General Manager, Children's Services has submitted a Councillor Janet supplementary report on this Item (CD5.9a for information) Davis Communication CD5.9.2 has been submitted on this Item. Planning and Growth Management Committee - Meeting 5 PG5.7 Canada Post Community Mailbox Program in Toronto Held Councillor David To be considered with Item TE7.106 Shiner PG5.12 Amendments to the Sign By-law and Related Fees (Ward All) Held Councillor David Shiner PG5.13 Electronic and Illuminated Sign Study and Recommendations for Held Amendments to Chapter 694 (Ward All) Councillor Justin J. -

Toronto City Council Enviro Report Card 2010-2014

TORONTO CITY COUNCIL ENVIRO REPORT CARD 2010-2014 TORONTO ENVIRONMENTAL ALLIANCE • JUNE 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY hortly after the 2010 municipal election, TEA released a report noting that a majority of elected SCouncillors had committed to building a greener city. We were right but not in the way we expected to be. Councillors showed their commitment by protecting important green programs and services from being cut and had to put building a greener city on hold. We had hoped the 2010-14 term of City Council would lead to significant advancement of 6 priority green actions TEA had outlined as crucial to building a greener city. Sadly, we’ve seen little - if any - advancement in these actions. This is because much of the last 4 years has been spent by a slim majority of Councillors defending existing environmental policies and services from being cut or eliminated by the Mayor and his supporters; programs such as Community Environment Days, TTC service and tree canopy maintenance. Only in rare instances was Council proactive. For example, taking the next steps to grow the Greenbelt into Toronto; calling for an environmental assessment of Line 9. This report card does not evaluate individual Council members on their collective inaction in meeting the 2010 priorities because it is almost impossible to objectively grade individual Council members on this. Rather, it evaluates Council members on how they voted on key environmental issues. The results are interesting: • Average Grade: C+ • The Mayor failed and had the worst score. • 17 Councillors got A+ • 16 Councillors got F • 9 Councillors got between A and D In the end, the 2010-14 Council term can be best described as a battle between those who wanted to preserve green programs and those who wanted to dismantle them. -

OCTOBER 2–6, 2018 Co-Presented with the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts

Artistic Director ILTER IBRAHIMOF OCTOBER 2–6, 2018 Co-presented with the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts FFDNORTH.COM 1 “Poetry in motion” ALVIN AILEY CIRCA – THE TIMES AMERICAN DANCE THEATER BALLET BC 440 Locust Street, Burlington “Brilliantly inventive! “Do not miss Gorgeous energy!” Free city parking on NOV this. It’s a – THE GUARDIAN (UK) wow!” EXPERIENCE evenings and weekends! 09 – HUFFINGTON 2018 POST Box Office905.681.6000 RIVETING burlingtonpac.ca FEB MAR Teasing Gravity DANCE CANADIAN 01-02 29-30 CONTEMPORARY 2019 2019 DANCE THEATRE FRI APR 5, 7PM TH HUMANS 60 ANNIVERSARY TOUR MIXED PROGRAMME Featuring street dancer AT BPAC Apolonia Velasquez, Rock Bottom Movement’s Alyssa Martin, Charles Moulton, famed for his ball passing BATSHEVA EIFMAN BALLET ORDER NOW FOR Made in Cuba spectaculars, and DANCE COMPANY ST. PETERSBURG BEST AVAILABILITY LIZT ALFONSO Jennifer Archibald DANCE CUBA “Seductive and beautiful” AND SAVE UP TO THURS FEB 21, 8PM APR – TIME OUT SYDNEY 30% WHEN YOU A love story told 09 PURCHASE ALL through evocative 2019 5 SHOWS! scenes of Cuban life Memory is the “Venezuela is FULL 5-SHOWS FROM $192.50 composed of bold, History of Forgetting powerful scenes FLEX-PACKS FROM $132.00 DREAMWALKER which knock your DANCE CO. insides around!” – THE JERUSALEM POST MAY FLEX-PACKS INCLUDE FRI OCT 26, 7:30PM CIRCA HUMANS, PLUS 2 OR 3 09-11 CO-PRESENTED BY Dancer Andrea Nann 2019 OTHER PERFORMANCES IN and Andy Maize from The Skydiggers bring THE DANCE COLLECTION. a transformative portrait of a profound VENEZUELA TCHAIKOVSKY. -

Guide to Safer Streets Near Schools

GUIDE TO SAFER STREETS NEAR SCHOOLS Understanding Your Policy Options September in the City of Toronto 2016 GUIDE TO SAFER STREETS NEAR SCHOOLS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 1 Summary 2 CHAPTER 1: Getting Started 3 Introduction to the Guide 3 Using the Guide 4 CHAPTER 2: The Paths 6 Path 1: Speed Limit Measures 6 Path 1A: 30km/h Speed Limit Policy 7 Path 1B: 40km/h Speed Limit Policy 8 Path 1C: District-wide Speed Limit Reduction 9 Path 2: Traffic Calming Measures 11 Traditional Traffic Calming Treatments 12 Other Safety Measures 14 Path 3: Improving Intersections and Major Crossings 15 Path 3A: Requesting a Crossing 16 Path 3B: All-Way Stop Signs 17 Path 3C: Improving an Existing Pedestrian Crossing 18 CHAPTER 3: Additional Resources 19 Research and Data to Support You 19 For More Information 21 Toolkit 25 A: Worksheet: Writing a Vision, Defining the Problems, Considering Options 26 B: Sample Email Template for Inviting Councillor to Meet 27 C: A Plan for Safer Streets Near Our School - Outreach Letter 28 D: Traffic Calming Petition 30 E: Sample Support Letter from School Administration/Council 31 F: Crossing Guards and Student Safety Patrollers 32 G: Bringing Transportation Safety into the Classroom 33 H: List of Organizations Working for Safer Streets 34 Photo Credits 36 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Partial support was provided by a seed grant from the Healthier Cities and Communities Hub Seed Grant initiative, a consortium of three Funding Partners: Toronto Public Health, The Wellesley Institute and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health. This work was also supported by Mitacs through the Mitacs-Accelerate Program. -

City Hall a TERM in REVIEW

City Hall A TERM IN REVIEW August 2018 1 As Toronto City Council has wrapped up its legislative term in anticipation of the upcoming Municipal Election in October, the Municipal Affairs Team at Sussex Strategy Group felt it was timely to reflect on the active 2014 - 2018 Council term. Below are some highlights from over the last four years, as well as some key insights into continued discussions and debates to be expected into the 2018 - 2022 term. Sussex has broken down the accomplishments and memorable moments into general trends of the term’s entirety. 2 Full Speed Ahead PUBLIC TRANSIT & TRANSPORTATION 3 Right out of the gate in early 2015, the by 2031, including approval of a SmartTrack accelerated SmartTrack work plan was concept with six new stations, an Eglinton reviewed and funded to address matters of West LRT, one-stop Scarborough subway project financing, design, service expectations extension, Eglinton East LRT, and a Relief Line. and implementation schedule over the course of the term. This was a key campaign promise of Mayor John Tory and properly aligned with one of the key themes of the term – getting Torontonians moving…out of their cars and onto transit. Getting Torontonians moving on the road safely and out of gridlock was another aspect of the 2014-2018 term. At the onset, Council approved measures to mitigate traffic disruptions. Next, Council focused its attention to speeding on residential streets and in school zones, a result of increased usage of cars trying to bypass congested arterial roads and routes. Staff reported on possible mitigation efforts in 2015.