Ancient Sparta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Sparta Was a Warrior Society in Ancient Greece That Reached

Ancient Sparta was a warrior society in ancient Greece that reached the height of its power after defeating rival city-state Athens in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.). Spartan culture was centered on loyalty to the state and military service. At age 7, Spartan boys entered a rigorous state-sponsored education, military training and socialization program. Known as the Agoge, the system emphasized duty, discipline and endurance. Although Spartan women were not active in the military, they were educated and enjoyed more status and freedom than other Greek women. Because Spartan men were professional soldiers, all manual labor was done by a slave class, the Helots. Despite their military prowess, the Spartans’ dominance was short-lived: In 371 B.C., they were defeated by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra, and their empire went into a long period of decline. SPARTAN SOCIETY Sparta was an ancient Greek city-state located primarily in the present-day region of southern Greece called Laconia. The population of Sparta consisted of three main groups: the Spartans who were full citizens; the Helots, or serfs/slaves; and the Perioeci, who were neither slaves nor citizens. The Perioeci, whose name means “dwellers-around,” worked as craftsmen and traders, and built weapons for the Spartans. 3 Layers of ‘Social Stratification’ ← Top Tier: Spartan Male Warriors and Spartan Women ← Middle Tier: Non Warriors, not full citizens, considered to be outside of true Spartan society. These were artisans and merchants who made weapons and did business with the Spartans. (Perioeci) ← Helots or slaves. These were people who were conquered by the Spartans. -

The Effects of Mythos' on Plato's Educational Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 55 ( 2012 ) 560 – 567 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON NEW HORIZONS IN EDUCATION INTE2012 The Effects of Mythos’ on Plato's Educational Approach Derya Çığır Dikyola aIstanbul University Hasan Ali Yucel Education Faculty, Department of Social Science, Istanbul, Turkey. Abstract The purpose of this study, by examining the findings related to education in Greek mythos, is to reveal Plato's contributions to the educational approach. The similarities and differences between Plato’s educational approach and the education in Mythos are emphasized in this historical - comparison based study. The effect of mythos, which in fact give ideal education of the period, with the expressions they made about Gods’ and heroes’ education, on the educational approach of Plato, known to be intensely against the mythos, is rather surprising. ©© 20122012 Published Published by byElsevier Elsevier Ltd. SelectionLtd. Selection and/or peer-reviewand/or peer-review under responsibility under responsibility of The Association of The of Association Science, of EducationScience, Educationand Technology and TechnologyOpen access under CC BY-NC-ND license. Keywords: educational approach, educational history, mythology. 1. Introduction Plato is the first thinker of philosophy as well as of education. His ideas about education still have influence on schooling. Thus; Plato is a decent starting point in the studies over the meaning and the philosophy of education. Thinkers like Aristoteles, John Locke, J. J. Rousseau, and John Dewey, who produced education theories couldn’t help challenging Plato. -

Not All Were Created Equal

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference 2010-2011 Past Young Historians Conference Winners May 1st, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM Not All Were Created Equal Sarah Cox Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Cox, Sarah, "Not All Were Created Equal" (2011). Young Historians Conference. 3. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2010-2011/oralpres/3 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Cox 1 Sarah Cox LPB Western Civilization: Fall Paper 9 December 2010 Not All Were Created Equal “The man’s role requires him to be outside – men who stay at home during the day are considered womanish – the woman’s requires her to work at home” (McAuslan 137). In the time-period between 700 and 300 BCE, this was often true for the women of the world, but there was one major exception: Spartan women. In most other parts of ancient Greece, women were expected to be seen and not heard. Spartan women, however, were allowed much more freedom than their contemporaries. They were allowed to own property, could live independently, and were not forced into marriage and motherhood at a young age. -

A Brief History of Classical Education

A Brief History of Classical Lesson 4: The History of Ancient Education Education Dr. Matthew Post Outline: Ancient Education and Its Questions Ancient Education is all about character formation. The question is “What sort of character?” What are the morals towards which to form students? Scholé presents another issue. Ancients had less time to devote to proper scholé. The presence of corporeal punishment was questioned by many because it seemed to treat students as slaves (coercing them to do their work through physical pain). The “intellectual life” caused controversy because it often raised questions that unsettled the normal order. (i.e. Cicero held that the ideas of the Stoics made people complacent in the face of evil and some held that Plato’s ideas inspired people to go and assassinate the ruler of their town) Roman Education Three outcomes: Philosopher, Statesman, and Soldier Discussion of Liberal Arts originates in Rome especially with Cicero (without formalization of Medieval period) Education connected to the idea of pietas (from which we get the English words “piety” and “pity”). Pietas does not mean “piety,” it means “loyalty.” o Pietas is loyalty to one’s family, people, city, and the gods. Loyalty to the gods is what the English notion of piety refers to, but pietas encompasses more. Traditional Roman education is dictated by the paterfamilias (the head of the family – a father with power over all and everything in the family). “Aeneas & Anchises” by Pierre Lepautre (a famous show of pietas) o The paterfamilias often educated the children himself. (Famously Cato the Elder educated his children.) Education in the Roman family was for both men and women though they were educated differently. -

Ancient Sparta Ancient Athens

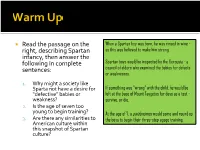

Read the passage on the When a Spartan boy was born, he was rinsed in wine - right, describing Spartan as this was believed to make him strong. infancy, then answer the following in complete Spartan boys would be inspected by the Gerousia - a sentences: council of elders who examined the babies for defects or weaknesses. 1. Why might a society like Sparta not have a desire for If something was “wrong” with the child, he would be “defective” babies or left at the base of Mount Taygetus for days as a test - weakness? survive, or die. 2. Is the age of seven too young to begin training? At the age of 7, a paidonómos would come and round up 3. Are there any similarities to the boys to begin their three-step agoge training. American culture within this snapshot of Spartan culture? Title: Comparative Study; Eastern Bloc and Worldly Civilizations Date: Know: I will be able to identify, describe, and analyze the similarities and differences of political involvement in livelihood across millennia. Relevance: Today we are learning about this because it is imperative to build knowledge in a pragmatic way – understanding that the real world and real life are connected to history is very important. Coming to this understanding is powerful! Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Ancient Greek city-states Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Medieval nations Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between modern countries Write down the Essential Question: EQ: which child-rearing system had the greatest impact on population regulation? Warm Up Cornell Notes . -

VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta Are to Be Found Those Who Are Most Enslaved and Those Who Are the Most Free.’

CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta are to be found those who are most enslaved and those who are the most free.’ CRITIAS OF ATHENS sample pages Spartan infantry in a formation called a phalanx. 38 39 CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA KEY POINTS KEY CONCEPTS OVERVIEW • At the end of the Dark Age, the Spartan polis emerged DEMOCRACY OLIGARCHY TYRANNY MONARCHY from the union of a few small villages in the Eurotas valley. Power vested in the hands Power vested in the hands A system under the control A system under the control • Owing to a shortage of land for its citizens, Sparta waged of all citizens of the polis of a few individuals of a non-hereditary ruler of a king war on its neighbour Messenia to expand its territory. unrestricted by any laws • The suppression of the Messenians led to a volatile slave or constitution population that threatened Sparta’s way of life, making the DEFINITION need for reform urgent. KEY EVENTS • A new constitution was put in place to ensure Sparta could protect itself from this new threat, as well as from tyranny. Citizens of the polis all A small, powerful and One individual exercises Hereditary rule passing 800 BCE • Sweeping reforms were made that transformed Sparta share equal rights in the wealthy aristocratic class complete authority over from father to son political sphere all aspects of everyday life Sparta emerges from the into a powerful military state that soon came to dominate Most citizens barred from Family dynasties claim without constraint Greek Dark Age the Peloponnese. -

Monday 16 June 2014 – Afternoon

F Monday 16 June 2014 – Afternoon GCSE CLASSICAL CIVILISATION A353/01 Community Life in the Classical World (Foundation Tier) *1238732213* Candidates answer on the Question Paper. OCR supplied materials: Duration: 1 hour None Other materials required: None *A35301* INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES • Write your name, centre number and candidate number in the boxes above. Please write clearly and in capital letters. • Use black ink. HB pencil may be used for graphs and diagrams only. • There are two options in this paper: Option 1: Sparta, with questions starting on page 2. Option 2: Pompeii, with questions starting on page 16. • Answer questions from either Option 1 or Option 2. • Answer all questions from Section A and two questions from Section B of the option that you have studied. • Read each question carefully. Make sure you know what you have to do before starting your answer. • Write your answer to each question in the space provided. If additional space is required, you should use the lined pages at the end of this booklet. The question number(s) must be clearly shown. • Do not write in the bar codes. INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES • The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. • The total number of marks for this paper is 60. • This document consists of 32 pages. Any blank pages are indicated. © OCR 2014 [A/501/5549] OCR is an exempt Charity DC (DTC 00708 10/12) 71715/3 Turn over 2 Option 1: Sparta Answer all of Section A and two questions from Section B. -

Agoge: Educational System for Sons of Spartiates

Agoge: Educational System for sons of Spartiates Atimia: Loss of Honour Gerousia: Council of elder noblemen Ekklesia: The Assembly Eirens: Older Youths aged 16-19 Ephorate: 5 Magistrates Homoioi: The Equals Klerois: The Land Allotment Kothon: Drinking cup popular for campaigns Krypteia: Secret Police Lakedaimonian: Spartans and Dwellers around from Lakonia Partheniai: Children of unmarried girls- speculated as offspring of unions of Spartan + helots Pelanors: Iron Bars used for currency Perioikoi: Householders surrounding Sparta who were not citizens Phratria: Brotherhood Rhetra: Oracles, Lykurgus’s laws Serfs: Helots Skias: Area containing tents Syssitia: Common Messes • What type of written source? • Who wrote the source? • Would they be in a position to have access to Sparta? • Date of source? • Audience of Source • Limitations of Source – incomplete, fragments of info, what does source not reveal Herodotus • Aim was to account for Greek and Persian wars (490- 479) • Digression of Spartans in Book 6 enlightens of attitudes to Spartans + military superiority • Leaves out later literary traditions of Sparta- this was not his intention Thuc • Thuc wrote about Sparta in Pelop period where Athens was hostile towards Spartan society • Provides info of Spartan warfare, workings of constitution + helots presented as back-ward- implausible as demonstrated through adaptable nature + Brasidas • Thuc is subjective + detached observer of Spartan society Xenohpon 4th Century • Following Sparta’s success of Peloponnesian war Xeno wrote ‘Constitution of the Lak’ as a pamphlet in praise of Sparta • Xenophon was Athenian but as a result of his exile became political + militarily involved with Sparta (Bias witness) • Xeno’s account can be considered excessive – draws attention to superiority of Sparta compared to other places • Although Xeno disapproves corrupt Spartan officials however down plays Krypteia Plutarch 2nd Century • Had access to Delphi + archives of shrine and a wide range of sources eg. -

The Commoner in Spartan History from the Lycurgan Reforms to the Death of Alexander: 776-322 B

THE COMMONER IN SPARTAN HISTORY FROM THE LYCURGAN REFORMS TO THE DEATH OF ALEXANDER: 776-323 B. C. By SHASTA HUTTON ABUALTIN fl Bachelor of Arts in Arts and Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1983 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1986 THE COMMONER I N SPARTAN HI STORY FROM THE LYCURGAN REFORMS TO THE DEATH OF ALEXANDER : 776- 323 B. C. Thesis Approv e d : Dean of t h e Graduate Colleg e 125"1196 ii PREFACE The ancient Greeks, their accomplishments, and their history have always facinated me. Further studies into Greek history developed an interest in the Spartans and their activities. So many of the ancient authors are if not openly, at least covertly, hostile to the Spartans. Many of the modern works are concerned only with the early or late history or are general surveys of the total history of Sparta while few works consider Sparta separate from the other Greek city-states in the classical period. My intention is to examine the role of the commoner in ancient Sparta. It must be emphasized that the use of "commoner" in this text refers to the Spartan citizens who were not kings. The Spartan slaves and other non-citizen groups are not included in the classification of commoners. This examination considers the lifestyle of the commoner, his various roles in the government, the better-known commoners, and the various conflicts which arose between the kings and the commoners. -

Thermopylae and Rise of an Empire

LIFE IN SPARTA 0. LIFE IN SPARTA - Story Preface 1. REVENGING MARATHON 2. SPARTA 3. LIFE IN SPARTA 4. LEONIDAS 5. GORGO 6. XERXES and the IMMORTALS 7. THERMOPYLAE 8. BATTLE at the HOT GATES 9. EPHIALTES - THE TRAITOR 10. THEMISTOCLES against XERXES 11. GREEKS DEFEAT the PERSIANS This image, depicting an engraving of Sparta, shows us that the town is situated in an agricultural valley. Mountains, including Mt. Taygetus, protect the town on three sides. Nearly thirty miles from Gythion, its port, ancient Sparta was not easy to blockade. Illustration online, courtesy Mitchell Teachers.org. Click on the image for a much-better view. At the time Xerxes and his army were traveling to Greece, Sparta was known for its military power. Ruled by two kings, plus a Council of Elders, Spartans knew that all male citizens would be part of the army. Training started at a very young age. Archeological evidence reveals, however, that Sparta was not always focused on military strength. During earlier times, craftsmen used bronze and ivory to produce beautiful objects. Many of these items were later found at religious sites, where they had been given as gifts to the gods. We can see a few of these examples at the British Museum: Bronze banqueter - probably made in Sparta between 530-500 BCE Bronze horse - probably made in Sparta around 700 BCE Bronze horse and rider - found in Armento, Italy. Life in Sparta took a different direction when its citizens began to rely on captives - called Helots - who were really Spartan slaves. The story of how Sparta changed into a military society is interesting. -

Youth Agoge- Education, in Ancient Sparta

Sumerianz Journal of Education, Linguistics and Literature, 2018, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 48-55 ISSN(e): 2617-1201, ISSN(p): 2617-1732 Website: https://www.sumerianz.com © Sumerianz Publication CC BY: Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 Original Article Open Access Youth Agoge- Education, in Ancient Sparta A Field Survey Researching Both "That Time" and "Present" Periods with Specific Reference to the Agoge-Education of Junior Girls Maria Karagianni MA Culture, Policy & Management-City University London, UK. MSc. Sustainable Development-Harokopio University of Athens, Greece Currently, working as a teacher in Greek Community of Toronto Schools in Toronto, Canada Abstract Our project is not a historical research, but based on secondary sources of historical information, it aims at probing Youth Agoge-Education in ancient Sparta. It seeks objectivity, describing aspects of the Spartan State. It compares the terms: "Agoge and education" of Sparta against the present terms. To support the project, a field survey shall be also used. The ultimate objective is the integrated scientific interpretation based on the findings of the field survey we have conducted in Athens. Keywords: 1. Introduction Sparta dates back to the 12th century BC. A time of rapid change for the ancient world, when Egypt was declining and the Second Babylonian Empire was emerging. According to a Greek legend, Sparta was violently established in 1152 BC, when the Dorians from the North who believed they were descendants of Hercules, invaded the south, claiming (according to their beliefs) that it was the land of their ancestors. As soon as the central peninsula of the Peloponnese was occupied, the king named it Laconia, and its capital "Sparta", after his queen. -

AH 1.3 Politics and Society of Ancient Sparta Maria Preztler

JACT Teachers’ Notes AH 1.3 Politics and Society of Ancient Sparta Maria Preztler 1.Introduction ............................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Books and resources ...................................................................................... 2 1.1.1. Annotated list of books cited in the notes .......................................... 2 1.2. Introduction to the sources ............................................................................. 4 1.2.1. Tyrtaeus .............................................................................................. 4 1.2.2. Herodotus ........................................................................................... 5 1.2.3. Thucydides ......................................................................................... 5 1.2.4. Aristophanes ...................................................................................... 6 1.2.5. Xenophon ........................................................................................... 6 1.2.6. Plutarch .............................................................................................. 7 1.2.7. Other sources ..................................................................................... 7 1.3. Background Information ................................................................................ 8 1.3.1. Chronological Overview .................................................................... 8 2. Notes on the Specification Bullet Points