The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter: a Study in Contextualization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

Radicalizing Romance: Subculture, Sex, and Media at the Margins

RADICALIZING ROMANCE: SUBCULTURE, SEX, AND MEDIA AT THE MARGINS By ANDREA WOOD A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Andrea Wood 2 To my father—Paul Wood—for teaching me the value of independent thought, providing me with opportunities to see the world, and always encouraging me to pursue my dreams 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Kim Emery, my dissertation supervisor, for her constant encouragement, constructive criticism, and availability throughout all stages of researching and writing this project. In addition, many thanks go to Kenneth Kidd and Trysh Travis for their willingness to ask me challenging questions about my work that helped me better conceptualize my purpose and aims. Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family who provided me with emotional and financial support at difficult stages in this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................7 ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................11 -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/97g9d23n Author Mewhinney, Matthew Stanhope Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki By Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alan Tansman, Chair Professor H. Mack Horton Professor Daniel C. O’Neill Professor Anne-Lise François Summer 2018 © 2018 Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney All Rights Reserved Abstract The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki by Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language University of California, Berkeley Professor Alan Tansman, Chair This dissertation examines the transformation of lyric thinking in Japanese literati (bunjin) culture from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. I examine four poet- painters associated with the Japanese literati tradition in the Edo (1603-1867) and Meiji (1867- 1912) periods: Yosa Buson (1716-83), Ema Saikō (1787-1861), Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) and Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916). Each artist fashions a lyric subjectivity constituted by the kinds of blending found in literati painting and poetry. I argue that each artist’s thoughts and feelings emerge in the tensions generated in the process of blending forms, genres, and the ideas (aesthetic, philosophical, social, cultural, and historical) that they carry with them. -

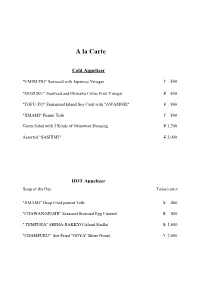

Muku Dinner Menu

A la Carte Cold Appetizer "UMIBUDO" Seaweed with Japanese Vinegar ¥ 800 "MOZUKU" Seaweed and Okinawa Citrus Fruit Vinegar ¥ 800 "TOFU-YO" Fermented Island Soy Curd with "AWAMORI" ¥ 800 "JIMAMI" Peanut Tofu ¥ 800 Green Salad with 3 Kinds of Okinawan Dressing ¥ 1,200 Assorted "SASHIMI" ¥ 3,000 HOT Appetizer Soup of the Day Today's price "JIMAMI" Deep Fried peanut Tofu ¥ 800 "CHAWAN-MUSHI" Seasonal Steamed Egg Custard ¥ 800 " TEMPURA" SHIMA-RAKKYO Island Shallot ¥ 1,000 "CHAMPURU" Stir-Fried "GOYA" Bitter Gourd ¥ 2,000 Chef's Special Dish ¥ 10,000 "Yakimono-Hassun" (Assorted small dishes) 11 kinds of Okinawan special small dishes on a big plate Grilled Ise Robster with butter Grilled Ishigaki beef Grilled Yambaru chicken with Ishigaki island salt Turban shell salad Deep-fried big-eye scad fish Tofu with oil bean paste and ishigaki beef Eel Sushi Shimeji mashrooms with soy sauce Jimami peanut Tofu Pickled roselle with sweet vinegar Various cracker Meat "YAMBARU-WAKADORI" Grilled Chicken with Teriyaki Sauce ¥ 2,500 "RAFTEA" Broil Stewed Cubes of Pork ¥ 3,000 "AGU SOKI ABURI" stewed pork spair ribs ¥ 3,500 Roasted Island "ISHIGAKI" Beef 80g ¥ 4,500 Roasted Island "ISHIGAKI" Beef 160g ¥ 9,000 "SHABU-SHABU SET" AGU Pork for two people ¥ 6,500 Extra AGU Pork 200g +¥2,500 Extra Okinawa Beef 200g +¥4,000 Seafood "TEMPURA" MOZUKU Seaweed ¥ 1,000 "GURUKUN KARAAGE" Deep-fried Black-tip fusilier fish Grilled Fish of the Day in butter ¥ 2,500 "TEMPURA" Island Shrimps and Vegetables ¥ 3,000 Rice & Noodles "JU-SHI" Okinawa Style Mixed Rice ¥ 800 Cold "ALOE" Udon Noodle ¥ 1,500 Hot Okinawa "SOBA" Noodles with "RAFTEA" ¥ 1,500 5 pieces of SUSHI ¥ 2,500 Dessert Ice Cream ¥ 500 Seasonal Dessert ¥ 800 Kid's Course ¥ 3,500 "DURUWAKASHI" Deep Fried TAIMO "SASHIMI" 2 Kinds of Islandfish "CHAWAN-MUSHI" Seasonal Egg Custard Grilled "AGU" Island Pork "JU-SHI" Okinawa Style Mixed Rice Dessert Kid's Plate ¥ 2,000 Humburg Steak / Fried Chicken Fried Shrimp / Fried Potato Salad Ice Cream. -

Tokimeku: the Poetics of Marie Kondo's Konmari Method

Flowers, Johnathan. “Tokimeku: The Poetics of Marie Kondo’s KonMari Method.” SPECTRA 7, no. 2 (2020): pp. 5–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21061/spectra.v7i2.146 ARTICLE Tokimeku: The Poetics of Marie Kondo’s KonMari Method Johnathan Flowers Worcester State University, US [email protected] Mono no aware is a poetic term developed by Motoori Norinaga to refer to the driving force behind aesthetic works, specifically poetry, and to refer to the human awareness of the qualitative nature of our experience in the world. For Norinaga, the cultivation of mono no aware necessarily leads to heightened sensitivity to both natural and man-made objects. As mono no aware is the natural response of the cultivated heart to the world around us, Norinaga takes it to be fundamental to human experience. Norinaga’s interpretation of the term aware as “to be stirred” bears striking similarities to the concept of “sparking joy” or tokimeku as used by Marie Kondo in her KonMari system. In Japanese, Kondo’s phrase “spark joy” is written as tokimeku, a word whose literal translation means “throb,” “pulsate,” or “beat fast,” as in the heart’s response to anticipation or anxiety. The aim of the present work is to make clear the connection between tokimeku in the KonMari system and Norinaga’s poetics of mono no aware. Specifically, this paper indicates the ways in which the KonMari system functions in line with a tradition of Japanese aesthetics of experience. This philosophy informs Japanese aesthetic practices and is articulated throughout Japanese poetics. This paper places Kondo in conversation with Norinaga’s work on aware and mono no aware towards a conceptualization of the KonMari system as an implement for cultivating a mindful heart. -

Flood Loss Model Model

GIROJ FloodGIROJ Loss Flood Loss Model Model General Insurance Rating Organization of Japan 2 Overview of Our Flood Loss Model GIROJ flood loss model includes three sub-models. Floods Modelling Estimate the loss using a flood simulation for calculating Riverine flooding*1 flooded areas and flood levels Less frequent (River Flood Engineering Model) and large- scale disasters Estimate the loss using a storm surge flood simulation for Storm surge*2 calculating flooded areas and flood levels (Storm Surge Flood Engineering Model) Estimate the loss using a statistical method for estimating the Ordinarily Other precipitation probability distribution of the number of affected buildings and occurring disasters related events loss ratio (Statistical Flood Model) *1 Floods that occur when water overflows a river bank or a river bank is breached. *2 Floods that occur when water overflows a bank or a bank is breached due to an approaching typhoon or large low-pressure system and a resulting rise in sea level in coastal region. 3 Overview of River Flood Engineering Model 1. Estimate Flooded Areas and Flood Levels Set rainfall data Flood simulation Calculate flooded areas and flood levels 2. Estimate Losses Calculate the loss ratio for each district per town Estimate losses 4 River Flood Engineering Model: Estimate targets Estimate targets are 109 Class A rivers. 【Hokkaido region】 Teshio River, Shokotsu River, Yubetsu River, Tokoro River, 【Hokuriku region】 Abashiri River, Rumoi River, Arakawa River, Agano River, Ishikari River, Shiribetsu River, Shinano -

Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: the Significance of “Women’S Art” in Early Modern Japan

Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gregory P. A. Levine, Chair Professor Patricia Berger Professor H. Mack Horton Fall 2010 Copyright by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto 2010. All rights reserved. Abstract Visual and Material Culture at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent: The Significance of “Women’s Art” in Early Modern Japan by Sharon Mitsuko Yamamoto Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Gregory Levine, Chair This dissertation focuses on the visual and material culture of Hōkyōji Imperial Buddhist Convent (Hōkyōji ama monzeki jiin) during the Edo period (1600-1868). Situated in Kyoto and in operation since the mid-fourteenth century, Hōkyōji has been the home for women from the highest echelons of society—the nobility and military aristocracy—since its foundation. The objects associated with women in the rarefied position of princess-nun offer an invaluable look into the role of visual and material culture in the lives of elite women in early modern Japan. Art associated with nuns reflects aristocratic upbringing, religious devotion, and individual expression. As such, it defies easy classification: court, convent, sacred, secular, elite, and female are shown to be inadequate labels to identify art associated with women. This study examines visual and material culture through the intersecting factors that inspired, affected, and defined the lives of princess-nuns, broadening the understanding of the significance of art associated with women in Japanese art history. -

Nintendo Wii

Nintendo Wii Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Another Code: R - Kioku no Tobira Nintendo Arc Rise Fantasia Marvelous Entertainment Bio Hazard Capcom Bio Hazard: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Bio Hazard 4: Wii Edition Capcom Bio Hazard 4: Wii Edition: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard 4: Wii Edition: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Bio Hazard Chronicles Value Pack Capcom Bio Hazard Zero Capcom Bio Hazard Zero: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard Zero: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Bio Hazard: The Darkside Chronicles Capcom Bio Hazard: The Darkside Chronicles: Collector's Package Capcom Bio Hazard: The Darkside Chronicles: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles: Wii Zapper Bundle Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Biohazard: Umbrella Chronicals Capcom Bleach: Versus Crusade Sega Bomberman Hudson Soft Bomberman: Hudson the Best Hudson Soft Captain Rainbow Nintendo Chibi-Robo! (Wii de Asobu) Nintendo Dairantou Smash Brothers X Nintendo Deca Sporta 3 Hudson Disaster: Day of Crisis Nintendo Donkey Kong Returns Nintendo Donkey Kong Taru Jet Race Nintendo Dragon Ball Z: Sparking! Neo Bandai Namco Games Dragon Quest 25th Anniversary Square Enix Dragon Quest Monsters: Battle Road Victory Square Enix Dragon Quest Sword: Kamen no Joou to Kagami no Tou Square Enix Dragon Quest X: Mezameshi Itsutsu no Shuzoku Online Square Enix Earth Seeker Enterbrain -

Modifying the Hague Convention? US Military Occupation of Korea and Japanese Religious Property in Korea, 1945–1948

Modifying the Hague Convention? US Military Occupation of Korea and Japanese Religious Property in Korea, 1945–1948 An Jong-Chol Acta Koreana, Volume 21, Number 1, June 2018, pp. 205-229 (Article) Published by Keimyung University, Academia Koreana For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/756456 [ Access provided at 27 Sep 2021 11:27 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] ACTA KOR ANA VOL. 21, NO. 1, JUNE 2018: 205–229 doi:10.18399/acta.2018.21.1.008 © Academia Koreana, Keimyung University, 2018 MODIFYING THE HAGUE CONVENTION? US MILITARY OCCUPATION OF KOREA AND JAPANESE RELIGIOUS PROPERTY IN KOREA, 1945–1948 By AN JONG-CHOL After World War II, the United States established the US Army Government in Korea (USAMGIK, 1945–48) in South Korea, and tried to justify its military occupation by international law, particularly the Hague Convention IV (1907). The Convention stipulates an occupant’s right to take all the measures necessary to restore public order and safety and his or her duty to respect the indigenous law. Considering the changed situation during World War II, however, where the military institutions of the Axis Powers drove their aggression into other countries, it was inevitable that the Allied Powers would modify the convention to apply it to the occupied countries. Since Japanese public or private property comprised the most wealth in colonial Korea, one of the key issues that USAMGIK faced in liberated Korea was how to handle former Japanese property, ultimately culminating in the confiscation of all Japanese property into the possession of USAMGIK. Thus, this article expounds this thorny issue by dealing with the rationale of this change of the international law, specifically a religious one, with the cy pres (as near as possible) principle, a category that USAMGIK handled with discretion compared to commercial or government property. -

Napoje Gazowane Soki Wody Mineralne Desery Kawy I Herbaty

DESERY 36 LODY MIZU 7 37 CHOCO MATCHA 21 38 JASUMIN FUWA FUWA 28 WODY MINERALNE NIEGAZOWANA 39 CISOWIANKA 0,3l 7 / 0,7l 12 GAZOWANA 40 CISOWIANKA PERLAGE 0,3l 7 / 0,7l 12 SOKI 41 SOK 0,25l 7 pomarańcza / jabłko czarna porzeczka / pomidor 42 SOK ŚWIEŻO WYCISKANY 0,3l 16 pomarańcza / grejpfrut NAPOJE GAZOWANE 43 BIO GALVANINA 0,3l 14 Bio Cola / lemoniada / mandarynka 44 NAPOJE GAZOWANE 0,2l 9 Coca Cola / Coca Cola Zero / Sprite / Tonic KAWY I HERBATY 45 LEMONIADA różne smaki 0,3l 14 / 1l 20 47 LATTE 12 46 DR COCO 0,25l 11 48 CAPPUCCINO 12 woda kokosowa 49 ESPRESSO DOPPIO 10 50 ESPRESSO / MACHIATO 8 51 ESPRESSO TONIC 15 52 HERBATA duża 12 / mała 8 zielona / jaśminowa / ryżowa / wiśniowa czarna PRZYSTAWKI SAŁATY I CIEPŁE WARZYWA 1 OKARA 9 13 MIDORI SARADA 24 mielona soja, błonnik z mleka sojowego, bok choy, szpinak, ogórek, edamame, marchewka, edamame, szczypiorek wodorosty, yuzu, żel miętowy 2 SZPINAK Z TOFU 12 14 EDAMAME 15 blanszowany szpinak, pasta z tofu strączki sojowe, sól morska 3 BUŁKA KAMO BAO 19 15 AGEBITASHI 14 bułka bao, kaczka, tsukemono, kolendra, sezonowe warzywa, dashi jalapeño ZUPY 4 PIEROŻKI BUTA GYOZA 5 szt. 18 wieprzowina, imbir, czosnek, 16 MISO SHIRU 18 kapusta pekińska, szczypiorek pasta sojowa, bulion dashi, tofu, grzyby 5 PIEROŻKI EBI GYOZA 5 szt. 22 17 SAKE MISO SHIRU 21 krewetki, imbir, czosnek, pasta sojowa, bulion dashi, tofu, kapusta pekińska, szczypiorek łosoś, grzyby 6 PIEROŻKI TOFU GYOZA 5 szt. 18 18 KAISEN MISO SHIRU 21 tofu, warzywa, edamame, imbir, czosnek, pasta sojowa, bulion dashi, tofu, kapusta pekińska, -

Rape in the Tale of Genji

SWEAT, TEARS AND NIGHTMARES: TEXTUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN HEIAN AND KAMAKURA MONOGATARI by OTILIA CLARA MILUTIN B.A., The University of Bucharest, 2003 M.A., The University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2015 ©Otilia Clara Milutin 2015 Abstract Readers and scholars of monogatari—court tales written between the ninth and the early twelfth century (during the Heian and Kamakura periods)—have generally agreed that much of their focus is on amorous encounters. They have, however, rarely addressed the question of whether these encounters are mutually desirable or, on the contrary, uninvited and therefore aggressive. For fear of anachronism, the topic of sexual violence has not been commonly pursued in the analyses of monogatari. I argue that not only can the phenomenon of sexual violence be clearly defined in the context of the monogatari genre, by drawing on contemporary feminist theories and philosophical debates, but also that it is easily identifiable within the text of these tales, by virtue of the coherent and cohesive patterns used to represent it. In my analysis of seven monogatari—Taketori, Utsuho, Ochikubo, Genji, Yoru no Nezame, Torikaebaya and Ariake no wakare—I follow the development of the textual representations of sexual violence and analyze them in relation to the role of these tales in supporting or subverting existing gender hierarchies. Finally, I examine the connection between representations of sexual violence and the monogatari genre itself.