Highways, Urban Renewal, and Patterns in the Built Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patriot Hills of Dallas

Patriot Hills of Dallas Background: After years of planning and market research our team assembled over 200+ - acres of prime Dallas property that was comprised of 8 separate properties. There is no record of any construction every being built on any of the 200 acres other than a homestead cabin. Much of the property was part of a family ranch used for grazing which is now overgrown with cedar and other species of trees and native grasses. Location: View property in the Dallas metroplex is one of the most unique features unmatched in the entire Dallas Fort Worth area. Most of the property is on a high bluff 100 feet above the surrounding area overlooking the Dallas Baptist University and the skyline of Fort Worth 21+ miles to the west. Convenient access to the greater Fort Worth and Dallas area by Interstate 20 and Interstate 30 Via Spur 408 freeways, Interstate 35, freeway 74, and the property is currently served by DART bus stops which provide connections to other mass transit options. The property is located 2 miles north of freeway 20 on the Spur 408 freeway and W. Kiest Blvd within the Dallas city limits. The property fronts on the East side of the Spur 408 freeway from Kiest Blvd exit on the North and runs continuous to the South to Merrifield Rd exit. The City of Dallas has plans to extend this road straight east to connect to West Ledbetter Drive that will take you directly to the Dallas Executive Airport and connecting on east with Freeway 67, Interstate 35 and Interstate 45. -

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

Kansas Lane Extension Regional Multi-Modal Connector

Department of Transportation Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD Transportation) Grants Program Kansas Lane Extension Regional Multi-Modal Connector City of Monroe, Louisiana May 2020 Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2 -- Application Snapshot ........................................................................................................ 3 Project Description ................................................................................................................. 4 Concise Description ............................................................................................................ 4 Transportation Challenges .................................................................................................. 7 Addressing Traffic Challenges ............................................................................................ 8 Project History .................................................................................................................... 9 Benefit to Rural Communities .............................................................................................. 9 Project Location .....................................................................................................................10 Grant Funds, Sources and Uses of Project Funds .................................................................12 Project budget ....................................................................................................................12 -

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP)

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP) Prepared By: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT JUNE 2015 Page is left blank intentionally for document formatting City of Atlanta 2016‐2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) and Community Work Program (CWP) June 2015 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Office of Planning 55 Trinity Avenue Suite 3350 Atlanta, GA 30303 http://www.atlantaga.gov/indeex.aspx?page=391 Online City Projects Database: http:gis.atlantaga.gov/apps/cityprojects/ Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adreaan Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Mary Norwood Andre Dickens Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development Terri M. Lee, Deputy Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Project Staff Jessica Lavandier, Assistant Director, Strategic Planning Rodney Milton, Principal Planner Lenise Lyons, Urban Planner Capital Improvements Program Sub‐Cabinet Members Atlanta BeltLine, -

AVAILABLE 7600 Antoine Road | Shreveport, LA

INDUSTRIAL SPACE AVAILABLE 7600 Antoine Road | Shreveport, LA ONNO STEGER | Director of Real Estate Phone | (614) 571-0012 E-mail | [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary Page 3 Building Overview Page 7 Area Overview Page 13 Logistics & Access Page 16 / Page 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY WEST SHREVEPORT INDUSTRIAL PARK West Shreveport Industrial Park is comprised of three buildings totaling nearly 3.5 Million SF including an associated warehouse/ manufacturing building Building One is an 840,000 SF former stamping plant; Building Two is a 1.6 Million SF manufacturing warehouse and paint facility; and the General Assembly building is 1 Million SF, the future home to Elio Motors. This plant includes 530 acres, located in a quality industrial park southwest of Shreveport, LA with access to city services and utilities. The General Assembly and former stamping plant buildings contain air-conditioned floor space and approximately 18 miles of conveyor line for assembly under one roof. Waste water treatment, heating, steam generation, deionized water, bulk-fluid transfer and air conditioning can be supplied by the plant’s powerhouse. HIGHLIGHTS » Construction: Insulated Metal Walls, Concrete Flooring » Sprinker: Wet » Access: I-20, I-49, 526, & 79/511 » Rail: On site, multiple active spurs, Union Pacific Railroad » 30’ Center clearance » 50’ Crane bay » 50’ x 50’ Column spacing » Docks and grade level doors » Heavy power » (2) 65-ton crane rails » 4,780 Parking spaces UTILITIES Southwestern Electric Power Electricity Supplier Company SWEPCO/AEP Centerpoint Energy and Renovan Natural Gas Supplier Landfill Gas Water Supplier City of Shreveport Sewer Supplier City of Shreveport Telecommunications ATT/Verizon/Comcast Supplier Fiber Optic Network Major Carriers / Page 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY HISTORY Construction of the original plant began in 1978 and was completed in 1981. -

PIONEER GARDENS 1102 State Highway 161 | Grand Prairie, Texas

PIONEER GARDENS 1102 State Highway 161 | Grand Prairie, Texas 322,824 SF | Class B Warehouse | 28’ Clear Height | Rail-Served Property Highlights Industrial Asset Rail-Served by Ample Lay-Down Yard 322,824 square feet of institutional-quality Union Pacific Approximately 2 acres that offers product in DFW’s premier submarket Four rail spurs, with two along the direct rail access and can be utilized west side and two leading directly to for outside storage, future building the north end of the building expansion or trailer storage Upgraded Office Space Loading Capability TENANCY 7,309 square feet of recently updated • 49 dock doors Home Depot leases the entire office space • 2 oversized drive-in doors building through July 2019 • 3 ramp doors PIONEER GARDENS 2 Location Highlights Premier Industrial Submarket • The Great Southwest / Arlington industrial submarket is one of the most robust 92.1 M SQUARE FEET & desirable distribution hubs within the DFW region • Located south of DFW Airport, the Property benefits from the strong overall Largest Industrial Submarket in DFW by growth in Dallas-Fort Worth and the continued relocation of major companies to Square Footage the region. 4.4M SQUARE FEET Accessibility Total Absorption through Q2 2018 • Centrally located in the heart of the Dallas - Fort Worth market with immediate access to multiple transportation nodes. • Pioneer Gardens benefits from surrounding desirable labor pools, as it attracts 4.8% VACANCY workers from the entire Dallas - Fort Worth region in Great Southwest • Features frontage -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Northside Drive Corridor Study Final Report – DRAFT B

Northside Drive Corridor Study Final Report – DRAFT B The City of Atlanta July 2005 Northside Drive Corridor Study – Final Report The City of Atlanta Shirley Franklin Mayor James Shelby Acting Commissioner, Department of Planning and Community Development Beverley Dockeray-Ojo Director, Bureau of Planning Lisa Borders, City Council President Carla Smith, District 1 Anne Fauver, District 6 Jim Maddox, District 11 Debi Starnes, District 2 Howard Shook, District 7 Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Ivory Lee Young, District 3 Clair Muller, District 8 Ceasar Mitchell, Post 1 at large Cleta Winslow, District 4 Felicia Moore, District 9 Mary Norwood, Post 2 at large Natalyn Archibong, District 5 C. T. Martin, District 10 H. Lamar Willis, Post 3 at large PREPARED BY Adam Baker, Atlantic Station, Laura Lawson, Northyard Corporation 1000 LLC Business Development Abernathy Road, Suite Tracy Bates, English Avenue Brian Leary, Atlantic Station 900, Atlanta, Georgia Community Development 30328 Tacuma Brown, NPU-T Scott Levitan, Georgia Institute of Technology Carrie Burnes, Castleberry Hill Bill Miller, Georgia World In Association With: Sule Carpenter, NPU-K PEQ, Urban Collage, Congress Center Richard Cheatham, NPU-E Key Advisors, Jordan, David Patton, NPU-M Jones, and Goulding Ned Drulard, Turner Properties Tony Pickett, Atlanta Housing Authority Robert Flanigan Jr., Spelman College CORE TEAM Jerome Russell, HJ Russell & Robert Furniss, Georgia Company Institute of Technology Alen Akin, Loring Heights D'Sousa Sheppard, Morris Harry Graham, Georgia Dept of Brown College Byron Amos, Vine City Civic Transportation Association Donna Thompson, Business Shaun Green, Home Park Owner Suzanne Bair, Marietta St. Community Improvement Assoc. Artery Association Amy Thompson, Loring Heights Meryl Hammer, NPU-C Community Pete Hayley, UCDC David Williamson, Georgia Institute of Technology Makeda Johnson, NPU-L Angela Yarbrough, Mt. -

Dixie Berryhill Strategic Plan

DIXIE BERRYHILL STRATEGIC PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Stakeholder Acknowledgements I Executive Summary 1 Part One: Introduction 6 Study Area Boundaries 6 Issues and Opportunities 8 Plan Purpose 9 Plan Development Process/Public Involvement 9 Plan Goals 10 Part Two: Area Profile 11 History and Background 11 Demographic Profile 15 Population Growth Forecast 15 Population Characteristics 16 Land Use 16 Existing Zoning 17 Employment Growth Forecast 19 Public Water and Sewer Service 21 Transportation Systems 23 Existing Conditions 23 Planned Improvements 23 Thoroughfare Plan 24 Sidewalks and Bikeways 26 Transit 26 Airport 28 Rail/Truck Inter-Modal Facility 28 Recreational Sites 29 Historic Sites 29 Environmental Profile 30 Catawba River 30 Water Resources 30 Water Quality Management 31 Topography 33 Soils 35 Slope-Soils Association 35 Vegetation 35 i PAGE Noise 36 Part Three: Vision Plan and Recommendations 37 Land Use and Urban Design Recommendations 37 Guiding Principles 37 Five Sub-Area Recommendations 40 Urban Design Guidelines 49 Site Development 53 Analysis and Inventory 53 Transportation System Recommendations 55 Environmental Recommendations 62 Open Space and Recreation Recommendations 63 Volume II: Implementation Strategies 65 Land Use and Urban Design 65 Transportation 66 Sewer and Water Utility Extensions 66 Open Space and Recreation 67 List of Maps Map 1 – Study Area 7 Map 2 – Existing Land Use 18 Map 3 – Existing Zoning 20 Map 4 – Water and Sewer 22 Map 5 – Transportation 25 Map 6 – Rapid Transit Corridors 27 Map 7 – Wetlands 32 Map 8 – Watershed and SWIM 34 Map 9 – Composite Land Use Map 38 Map 10 –Transit Mixed Use Community 41 Map 11 – Mixed Use Community A 43 Map 12 – Mixed Use Community B and C 45 Map 13 – Mixed Use Community D 48 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Charlotte Mecklenburg Planning Commission extends our deepest gratitude to the members of our stakeholder group that consisted of property owners, residents, realtors, developers, City and County staff and the Chamber of Commerce. -

Atlanta, Georgia December 2001 Livable Centers Initiative City Center Table of Contents

Livable Centers Initiative City Center Central Atlanta Progress Georgia State University Historic District Development Corporation The Housing Authority of the City of Atlanta, Georgia Atlanta, Georgia December 2001 Livable Centers Initiative City Center Table of Contents Acknowledgments 2 Foreward 3 Framework for Livable Centers 5 The Big Ideas 13 1. Strengthen Neighborhoods 16 2. Park Once 20 3. Fill in the Gaps 24 4. Support the Downtown Experience 30 Central Atlanta Progress Georgia State University Historic District Development Corporation Housing Authority of the City of Atlanta 1 Acknowledgements The City Center Livability Partners thank all the citizen planners who participated in this project. City Center Livability Partners Central Atlanta Progress, Inc. Georgia State University Historic District Development Corporation The Housing Authority of the City of Atlanta, Georgia Additional Steering Committee Members Atlanta Regional Commission City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation, Bureau of Planning Fairlie-Poplar Implementation Task Force Georgia Building Authority Grady Heath Systems National Park Service, Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Site Consultants EDAW, Inc. Day Wilburn and Associates, Inc. Trinity Plus One Consultants, Inc. Central Atlanta Progress Georgia State University Historic District Development Corporation Housing Authority of the City of Atlanta 2 Foreward As late as the 1960s, Downtown Atlanta was a bustling place, center of the Southeast and the place to work and shop. Little by little, as the city lost population and resources, and competition in the suburbs increased, Downtown began to lose its vibrancy. Businesses and government agencies began to move out and surrounding neighborhoods slipped into decay. The trend lines turned positive in the 1990s. -

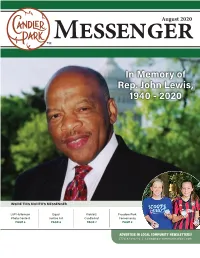

In Memory of Rep. John Lewis, 1940 - 2020

August 2020 TM News for Candler Park • Your In Town Hometown • www.CandlerPark.org In Memory of Rep. John Lewis, 1940 - 2020 INSIDE THIS MONTH’S MESSENGER L5P Halloween Equal Kids biz: Freedom Park Photo Contest Justice Art Candle Hut Conservancy PAGE 4 PAGE 6 PAGE 7 PAGE 9 WE ARE HERE FOR OUR COMMUNITIES SAVE 10% (UP TO $1,500) Active FOR OUR FRONT LINE Military & RESPONDERS Law *Expires 8/31/20 Veterans Enforcement EMT & Paramedics . Teachers Fire Fighters . Doctors & Nurses WATER YOUR HEATING, COOLING & CLEAN AIR EXPERTS $1,500 OFF HEATERS A NEW HIGH EFFICIENCY, FOR AS LOW AS QUALIFYING, RHEEM $20/MO SYSTEM *Expires 8/31/20 *Expires 8/31/20 770-445-0870 • Call us for more information The mission of the Candler Park Neighborhood Organization is to promote the common good and general welfare in the neighborhood known as Candler Park in the city of Atlanta. BOARD of DIRECTORS PRESIDENT Matt Kirk [email protected] MEMBERSHIP OFFICER Jennifer Wilds [email protected] TREASURER Karin Mack [email protected] SECRETARY Bonnie Palter [email protected] ZONING OFFICER Emily Taff [email protected] PUBLIC SAFETY OFFICER Lexa King [email protected] COMMUNICATIONS OFFICER Ryan Anderson [email protected] Photo credit: AP News FUNDRAISING OFFICER Matt Hanson [email protected] EXTERNAL AFFAIRS OFFICER Amy Stout Rest in Power, Congressman Lewis [email protected] Find a complete list of CPNO committee By Matt Kirk, [email protected] chairs, representatives and other contacts at www.candlerpark.org. On July 17, 2020, this world, the city of Atlanta, and Candler Park lost a true civil rights Presidential Briefing MEETINGS icon and human rights advocate. -

2.0 Development Plan

2.0 Development Plan 2.1 Community Vision 2.2 LCI Study Area Concept Plan 2.3 Short-Term Priorities 2.4 Mid-Term Priorities 2.5 Long-Term Priorities 2.6 Corridor Development Program JSA McGill LCI Plan Prepared by: Urban Collage, Inc. in association with Cooper Carry, URS Corp., HPE, ZVA, ZHA, Verge Studios, Biscuit Studios & PEQ JSA- McGill LCI Study Community Vision 2.1 Community Vision A significant portion of the work done on the JSA-McGill LCI study involved public participation, and this took many different forms. As part of the Imagine Downtown process, JSA was publicized as one of five focus areas requiring planning attention. Dates and times of all public events were posted on the Central Atlanta Progress website (www.atlantadowntown.com). E-mail comments were welcomed and encouraged. Several questions in the online ‘Imagine Survey’ were directed toward development in the JSA-McGill corridor. The centerpieces of the public involvement process were three public workshops; the second being a three-day long ‘Charette Week’ designed to build awareness and excitement through an intense set of collaborative exercises. 2.1.1 Public Workshop 1 The first public workshop was held on August 19, 2003 on the 27th floor of SunTrust Tower; over 200 persons attended. The purpose was to kick off the JSA-McGill LCI process by introducing the project and the team, and to conduct interactive exercises to gauge the initial level of consensus on issues and priorities. The workshop opened with a welcome and introduction by representatives of Central Atlanta Progress, and continued with words and graphics describing the developing programs and potential impact of both the Georgia Aquarium and the World of Coca-Cola.