Nonreductive Physicalism Cannot Appeal to Token

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17. Idealism, Or Something Near Enough Susan Schneider (In

17. Idealism, or Something Near Enough Susan Schneider (In Pearce and Goldsmidt, OUP, in press.) Some observations: 1. Mathematical entities do not come for free. There is a field, philosophy of mathematics, and it studies their nature. In this domain, many theories of the nature of mathematical entities require ontological commitments (e.g., Platonism). 2. Fundamental physics (e.g., string theory, quantum mechanics) is highly mathematical. Mathematical entities purport to be abstract—they purport to be non-spatial, atemporal, immutable, acausal and non-mental. (Whether they truly are abstract is a matter of debate, of course.) 3. Physicalism, to a first approximation, holds that everything is physical, or is composed of physical entities. 1 As such, physicalism is a metaphysical hypothesis about the fundamental nature of reality. In Section 1 of this paper, I urge that it is reasonable to ask the physicalist to inquire into the nature of mathematical entities, for they are doing heavy lifting in the physicalist’s approach, describing and identifying the fundamental physical entities that everything that exists is said to reduce to (supervene on, etc.). I then ask whether the physicalist in fact has the resources to provide a satisfying account of the nature of these mathematical entities, given existing work in philosophy of mathematics on nominalism and Platonism that she would likely draw from. And the answer will be: she does not. I then argue that this deflates the physicalist program, in significant ways: physicalism lacks the traditional advantages of being the most economical theory, and having a superior story about mental causation, relative to competing theories. -

Comment Attachment

Nuriel Moghavem, MD University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA [email protected] Victor W. Henderson, MD Stanford University, Stanford, CA Michael D. Greicius, MD, MPH Stanford University, Stanford, CA Disclosure: Dr. Greicius is a co-founder and share-holder of SBGneuro Chrysa Cheronis, MD Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, CA Wesley Kerr, MD, PhD University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI Alberto Espay, MD University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center, Cincinnati, OH Daniel O. Claassen MD Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Bruce T. Adornato MD Adjunct Clinical Professor of Neurology, Palo Alto, CA Roger L. Albin, MD University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI R. Ryan Darby, MD Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Graham Garrison, MD University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio Lina Chervak, MD University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH Abhimanyu Mahajan, MD, MHS Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL Richard Mayeux, MD Columbia University, New York, NY Lon Schneider MD Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CAv Sami Barmada, MD PhD University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI Evan Seevak, MD Alameda Health System, Oakland, CA Will Mantyh MD University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN Bryan M. Spann, DO, PhD Consultant, Cognitive and Neurobehavior Disorders, Scottsdale, AZ Kevin Duque, MD University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH Lealani Mae Acosta, MD, MPH Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Marie Adachi, MD Alameda Health System, Oakland, CA Marina Martin, MD, MPH Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA Matthew Schrag MD, PhD Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Matthew L. Flaherty, MD University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH Stephanie Reyes, MD Durham, NC Hani Kushlaf, MD University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH David B Clifford, MD Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri Marc Diamond, MD UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX Disclosure: Dr. -

Living in a Matrix, She Thinks to Herself

y most accounts, Susan Schneider lives a pretty normal life. BAn assistant professor of LIVING IN philosophy, she teaches classes, writes academic papers and A MATrix travels occasionally to speak at a philosophy or science lecture. At home, she shuttles her daughter to play dates, cooks dinner A PHILOSOPHY and goes mountain biking. ProfESSor’S LifE in Then suddenly, right in the middle of this ordinary American A WEB OF QUESTIONS existence, it happens. Maybe we’re all living in a Matrix, she thinks to herself. It’s like in the by Peter Nichols movie when the question, What is the Matrix? keeps popping up on Neo’s computer screen and sets him to wondering. Schneider starts considering all the what-ifs and the maybes that now pop up all around her. Maybe the warm sun on my face, the trees swishing by and the car I’m driving down the road are actually code streaming through the circuits of a great computer. What if this world, which feels so compellingly real, is only a simulation thrown up by a complex and clever computer game? If I’m in it, how could I even know? What if my real- seeming self is nothing more than an algorithm on a computational network? What if everything is a computer-generated dream world – a momentary assemblage of information clicking and switching and running away on a grid laid down by some advanced but unknown intelligence? It’s like that time, after earning an economics degree as an undergrad at Berkeley, she suddenly switched to philosophy. -

A Diatribe on Jerry Fodor's the Mind Doesn't Work That Way1

PSYCHE: http://psyche.cs.monash.edu.au/ Yes, It Does: A Diatribe on Jerry Fodor’s The Mind Doesn’t Work that Way1 Susan Schneider Department of Philosophy University of Pennsylvania 423 Logan Hall 249 S. 36th Street Philadelphia, PA 19104-6304 [email protected] © S. Schneider 2007 PSYCHE 13 (1), April 2007 REVIEW OF: J. Fodor, 2000. The Mind Doesn’t Work that Way. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 144 pages, ISBN-10: 0262062127 Abstract: The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way is an expose of certain theoretical problems in cognitive science, and in particular, problems that concern the Classical Computational Theory of Mind (CTM). The problems that Fodor worries plague CTM divide into two kinds, and both purport to show that the success of cognitive science will likely be limited to the modules. The first sort of problem concerns what Fodor has called “global properties”; features that a mental sentence has which depend on how the sentence interacts with a larger plan (i.e., set of sentences), rather than the type identity of the sentence alone. The second problem concerns what many have called, “The Relevance Problem”: the problem of whether and how humans determine what is relevant in a computational manner. However, I argue that the problem that Fodor believes global properties pose for CTM is a non-problem, and that further, while the relevance problem is a serious research issue, it does not justify the grim view that cognitive science, and CTM in particular, will likely fail to explain cognition. 1. Introduction The current project, it seems to me, is to understand what various sorts of theories of mind can and can't do, and what it is about them in virtue of which they can or can't do it. -

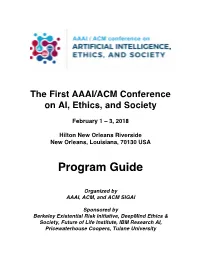

Program Guide

The First AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society February 1 – 3, 2018 Hilton New Orleans Riverside New Orleans, Louisiana, 70130 USA Program Guide Organized by AAAI, ACM, and ACM SIGAI Sponsored by Berkeley Existential Risk Initiative, DeepMind Ethics & Society, Future of Life Institute, IBM Research AI, Pricewaterhouse Coopers, Tulane University AIES 2018 Conference Overview Thursday, February Friday, Saturday, 1st February 2nd February 3rd Tulane University Hilton Riverside Hilton Riverside 8:30-9:00 Opening 9:00-10:00 Invited talk, AI: Invited talk, AI Iyad Rahwan and jobs: and Edmond Richard Awad, MIT Freeman, Harvard 10:00-10:15 Coffee Break Coffee Break 10:15-11:15 AI session 1 AI session 3 11:15-12:15 AI session 2 AI session 4 12:15-2:00 Lunch Break Lunch Break 2:00-3:00 AI and law AI and session 1 philosophy session 1 3:00-4:00 AI and law AI and session 2 philosophy session 2 4:00-4:30 Coffee break Coffee Break 4:30-5:30 Invited talk, AI Invited talk, AI and law: and philosophy: Carol Rose, Patrick Lin, ACLU Cal Poly 5:30-6:30 6:00 – Panel 2: Invited talk: Panel 1: Prioritizing The Venerable What will Artificial Ethical Tenzin Intelligence bring? Considerations Priyadarshi, in AI: Who MIT Sets the Standards? 7:00 Reception Conference Closing reception Acknowledgments AAAI and ACM acknowledges and thanks the following individuals for their generous contributions of time and energy in the successful creation and planning of AIES 2018: Program Chairs: AI and jobs: Jason Furman (Harvard University) AI and law: Gary Marchant -

JOSEPH CORABI, Ph.D

Department of Philosophy Saint Joseph’s University 5600 City Avenue Philadelphia, PA 19131 Phone: 610-660-1541 E-mail: [email protected] JOSEPH CORABI, Ph.D. Education Rutgers University, 2001-2007 Ph.D. in Philosophy, October 2007 Saint Joseph’s University, 1997-2001 Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy University Scholar in Philosophy Summa cum Laude Areas of Specialization Philosophy of Mind, Philosophy of Religion Areas of Competence Metaphysics, Epistemology, Metaethics, Normative Ethics, Applied Ethics, Moral Psychology, Logic Research Articles “The Evidential Weight of Social Evil,” Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Religion 8, pp. 47-70 (2017). “Two Arguments For Impossibilism and Why it Isn’t Impossible to Refute Them,” Philosophia 45, pp. 569-584 (2017). “Free Will,” in Brian McLaughlin (ed.), Philosophy of Mind (Cengage-Macmillan), pp. 189-207 (2017) “Superintelligence as Moral Philosopher,” forthcoming in Journal of Consciousness Studies “Superintelligent AI and Skepticism,” forthcoming in Journal of Evolution and Technology “Purified by Supervenience: A Case Study On the Uses of Supervenience in Confirmation,” Metodo 3(2), pp. 149-170 (2015) “The Misuse and Failure of the Evolutionary Argument,” Disputatio 39 (6), pp. 199-227 (November 2014) “If You Upload, Will You Survive?,” (with Susan Schneider), in Russell Blackford and Damien Broderick (eds.), Intelligence Unbound (Wiley-Blackwell), pp. 131-145 (2014) “Prophecy, Foreknowledge, and Middle Knowledge” (with Rebecca Germino), Faith and Philosophy 30(1), pp. 72-92 (January 2013) “The Metaphysics of Uploading,” (with Susan Schneider) Journal of Consciousness Studies 19(7-8), pp. 26-44 (July-August 2012) “Eschatological Cutoffs,” Faith and Philosophy 28(4), pp. 385-396 (October 2011) “Hell and Character,” Religious Studies 47(2), pp. -

Panpsychism, Panprotopsychism, and Neutral Monism Donovan Wishon Assistant Professor of Philosophy University of Mississippi, Oxford

CHAPTER 3 Panpsychism, Panprotopsychism, and Neutral Monism Donovan Wishon Assistant Professor of Philosophy University of Mississippi, Oxford In our endeavour to understand reality we are somewhat like a man trying to understand the mechanism of a closed watch. He sees the face and the moving hands, even hears its ticking, but he has no way of opening the case. —Albert Einstein and Leopold Infeld, The Evolution of Physics (1938) In everyday life, we generally suppose that conscious mental lives are relatively rare occurrences in nature—enjoyed by humans and select species of animals—especially when reflecting on the vast scale of the cosmos and its history. By all appearances, this natural conviction receives enormous support from the picture of the natural world provided by physics, astronomy, chemistry, biology, geology, and other branches of the physical sciences. In general outline, this scientific picture characterizes consciousness as a relatively recent product of the long course of the earth’s natural and evolutionary history whose emergence is intimately linked, in some fashion, to the highly complex functioning of the brains and central nervous systems of certain sophisticated biological organisms residing at or near the planet’s surface. Against this background, philosophical and empirical questions about the distribution of minded beings in nature typically concern when and where consciousness and thought first came onto the scene and which highly evolved biological organisms do, in fact, enjoy conscious mental lives. In a more speculative frame of mind, we might wonder whether computers, robots, or other inorganic systems are, in principle, capable of genuine thought and/or experience (see the “The Computational Theory of Mind” and “The Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence” chapters elsewhere in this volume). -

On Susan Schneider's Artificial

On Susan Schneider’s Artificial You: the twin problem of AI and lab-grown brain consciousness Ho Manh Tung Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University Beppu, Oita, Japan November 4, 2020 A recent article in Nature discusses the problem of consciousness in lab-grown cerebral organoids (Reardon, 2020). In the case of lab-grown brains, it seems very intuitively likely that they will become conscious once certain level of mass is achieved. In the case of artificial intelligence (AI), given their non-biological nature, it is harder to imagine how AI can become conscious. There is no better place to start educating yourself about the problem of AI consciousness than Susan Schneider’s Artificial You: AI and the future of your mind (2019). The book starts with classifying two mainstream positions regarding AI consciousness: biological naturalism and techno-optimism. Biological naturalism views consciousness is an intrinsic property of biological systems and it is impossible to replicate it in non-biological systems like machines or computers, roughly speaking. Techno-optimism is the view held by many contemporary AI experts, who think that given that most, if not all, processes in the brain are computational, our technological and scientific advances will eventually deliver AI consciousness. Then Schneider proposes the middle way: The wait-and-see approach, in which, she recognizes the validity of the arguments of both sides, yet, whether we will have conscious AI will depend on so many unknown unknowns: political changes, PR disasters, and most important of all, scientific discoveries. That means being totally committed to one side is a mistake. -

The Metaphysics of Uploading

Joseph Corabi and Susan Schneider The Metaphysics of Uploading Introduction Metaphysics is a matter of life and death. When it comes to making a decision about whether to upload when the singularity hits, the devil is in the metaphysical details about the nature of substance and proper- ties, or so we’ll urge. An upload is a creature that has its thoughts and sensations transferred from a physiological basis in the brain to a com- putational basis in computer hardware. An upload could have a virtual or simulated body or even be downloaded into an android body — indeed, an upload could even primarily exist in the digital world, and merely occupy an android body when needed. Imagine life as an upload. From a scheduling perspective, things are quite convenient: on Monday at 6pm, you could have an early din- ner in Rome; by 7:30pm, you could be sipping wine nestled in the hills of the Napa Valley; you need only rent a suitable android in each locale. Airports are a thing of the past for you. Bodily harm matters lit- tle — you just pay a fee to the rental company when your android is injured or destroyed. Formerly averse to risk, you find yourself skydiving for the first time in your life. You climb Everest. You think: if I continue to diligently back-up, I can live forever. What a surpris- ing route to immortality. But wait! Metaphysics is not on your side. As we’ll now explain, the philosophical case for surviving uploading is weak. When you upload, you are probably dying. -

SUSAN SCHNEIDER Department of Philosophy the University of Connecticut, Storrs Email: [email protected] Homepage: Schneiderwebsite.Com

SUSAN SCHNEIDER Department of Philosophy The University of Connecticut, Storrs Email: [email protected] Homepage: SchneiderWebsite.com Academic Appointments Associate Professor of Philosophy, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Conn. (2012 – present.) Faculty member, Cognitive Science Program, The University of Connecticut. Faculty member, Connecticut Institute for Brain and Cognitive Science, The University of Connecticut. Technology and Ethics Group, Yale Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. (Spring 2015-present). Research Fellow, Center for Theological Inquiry, (NASA project on the origin of life), Princeton, NJ. (2015-present). Research Fellow, American Council of Learned Societies, 2013-1014. Research Fellow, Research School of the Social Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. 2013. Assistant Professor of Philosophy, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (2006- 2012). (Teaching load: 2/2.) Faculty member, Center for Neuroscience and Society Faculty member, Institute for Research in Cognitive Science Faculty member, Center for Cognitive Neuroscience Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Moravian College (2003–2006). Research Specializations Philosophy of Mind, Metaphysics, Applied Ethics, Philosophy of Science Areas of Teaching Competence Epistemology, Modern Philosophy, Ancient Philosophy, Philosophy of Language, Philosophy of Mathematics Education Ph.D., Philosophy, (Dec., 2003), Rutgers University, Dept. of Philosophy. 1 B.A., Economics, (with honors), University of California at Berkeley, 1993. Books 1. The Language of Thought: A New Philosophical Direction, (2011). Cambridge: MIT Press. (Monograph, 259 pp.) Paperback edition – Spring, 2015. 2. Science Fiction and Philosophy, (2009). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. (Anthology, 350 pages). Second Edition, Fall 2015. Portuguese translation – Madras Editora Ltda., Brazil, 2010. Arabic translation – Ntl. Center for Translation, Egypt, 2011. Croatian translation (in progress). 3. The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness, (2007). -

The Language of Thought a New Philosophical Direction

The Language of Thought A New Philosophical Direction The Language of Thought A New Philosophical Direction Susan Schneider The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, re- cording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. For information about special quantity discounts, please email special_ [email protected] This book was set in Stone by the MIT Press. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schneider, Susan, 1968– The language of thought : a new philosophical direction / Susan Schneider. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-01557-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Philosophy of mind. 2. Cognitive science—Philosophy. 3. Thought and thinking—Philosophy. 4. Fodor, Jerry A. I. Title. BD418.3.S36 2011 153.4—dc22 2010040700 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Rob, Jo, Denise, and Ally Contents Preface ix 1 Introduction 1 2 The Central System as a Computational Engine 27 3 Jerry Fodor’s Globality Challenge to the Computational Theory of Mind 65 with Kirk Ludwig 4 What LOT’s Mental States Cannot Be: Ruling out Alterna- tive Conceptions 91 5 Mental Symbols 111 6 Idiosyncratic Minds Think Alike: Modes of Presentation Reconsidered 135 7 Concepts: A Pragmatist Theory 159 8 Solving the Frege Cases 183 9 Conclusion 229 References 233 Index 249 Preface This project started when certain of the language of thought program’s central philosophical commitments struck me as ill conceived. -

The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness

THE BLACKWELL COMPANION TO CONSCIOUSNESS Max Velmans Susan Schneider Science Editor Philosophy Editor Advisory Editors Science of Consciousness: Jeff rey Gray, John Kihlstrom, Phil Merikle, Stevan Harnad Philosophy of Consciousness: Ned Block, David Chalmers, José Bermúdez, Brian McLaughlin, George Graham Th e Blackwell Companion to Consciousness THE BLACKWELL COMPANION TO CONSCIOUSNESS Max Velmans Susan Schneider Science Editor Philosophy Editor Advisory Editors Science of Consciousness: Jeff rey Gray, John Kihlstrom, Phil Merikle, Stevan Harnad Philosophy of Consciousness: Ned Block, David Chalmers, José Bermúdez, Brian McLaughlin, George Graham © 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148–5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia Th e right of Max Velmans and Susan Schneider to be identifi ed as the Authors of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2007 Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Th e Blackwell companion to consciousness / edited by Max Velmans, science editor and Susan Schneider, philosophy editor p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN- 13: 978–1– 4051–2019–7 (hardback) ISBN- 13: 978–1– 4051–6000–1 (pbk.) 1. Consciousness.