Mammal Inventory of the Mojave Network Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory of Terrestrial Mammals in the Rincon Mountains Using Camera Traps

Inventory of Terrestrial Mammals in the Rincon Mountains Using Camera Traps Don E. Swann and Nic Perkins Saguaro National Park, Tucson, Arizona Abstract— The Sky Island region of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico is well-known for its diversity of mammals, including endemic species and species representing several different biogeo- graphic provinces. Camera trap studies have provided important insight into mammalian distribution and diversity in the Sky Islands in recent years, but few studies have attempted systematic inventories of one or more mountain ranges with a repeatable, randomized study design. We surveyed medium and large terrestrial mammals of the Rincon Mountains within Saguaro National Park, and compared the results with previous surveys of the Rincons. We sampled in random locations in four elevational strata from May 2011 through April 2012. We detected 23 native species of mammals and estimated species richness to be 24.8 species. We failed to detect four native species documented by other methods during 1999-2012, as well as five species (bighorn sheep, grizzly bear, jaguar, gray wolf, and North American porcupine) documented during 1900-1999 that may be extirpated from the Rincons. Advances in camera trap technology, as well an expanding use of this technology by educators and the public, suggest this method has the potential to be a cost-effective and reliable method for both inventory and long-term monitoring of terrestrial mammals of Sky Island region. Introduction using a randomized, repeatable study design that allows estimates to be made of measures such as native species richness (the number The Sky Island region of the southwestern United States and of native species that occur in an area). -

Eagle Crest Energy Gen-Tie and Water Pipeline Environmental

Eagle Crest Energy Gen-Tie and Water Pipeline Environmental Assessment and Proposed California Desert Conservation Area Plan Amendment BLM Case File No. CACA-054096 BLM-DOI-CA-D060-2016-0017-EA BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT California Desert District 22835 Calle San Juan De Los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 April 2017 USDOI Bureau of Land Management April 2017Page 2 Eagle Crest Energy Gen-Tie and Water Pipeline EA and Proposed CDCA Plan Amendment United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT California Desert District 22835 Calle San Juan De Los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 April XX, 2017 Dear Reader: The U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has finalized the Environmental Assessment (EA) for the proposed right-of-way (ROW) and associated California Desert Conservation Area Plan (CDCA) Plan Amendment (PA) for the Eagle Crest Energy Gen- Tie and Water Supply Pipeline (Proposed Action), located in eastern Riverside County, California. The Proposed Action is part of a larger project, the Eagle Mountain Pumped Storage Project (FERC Project), licensed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in 2014. The BLM is issuing a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) on the Proposed Action. The FERC Project would be located on approximately 1,150 acres of BLM-managed land and approximately 1,377 acres of private land. Of the 1,150 acres of BLM-managed land, 507 acres are in the 16-mile gen-tie line alignment; 154 acres are in the water supply pipeline alignment and other Proposed Action facilities outside the Central Project Area; and approximately 489 acres are lands within the Central Project Area of the hydropower project. -

California Vegetation Map in Support of the DRECP

CALIFORNIA VEGETATION MAP IN SUPPORT OF THE DESERT RENEWABLE ENERGY CONSERVATION PLAN (2014-2016 ADDITIONS) John Menke, Edward Reyes, Anne Hepburn, Deborah Johnson, and Janet Reyes Aerial Information Systems, Inc. Prepared for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife Renewable Energy Program and the California Energy Commission Final Report May 2016 Prepared by: Primary Authors John Menke Edward Reyes Anne Hepburn Deborah Johnson Janet Reyes Report Graphics Ben Johnson Cover Page Photo Credits: Joshua Tree: John Fulton Blue Palo Verde: Ed Reyes Mojave Yucca: John Fulton Kingston Range, Pinyon: Arin Glass Aerial Information Systems, Inc. 112 First Street Redlands, CA 92373 (909) 793-9493 [email protected] in collaboration with California Department of Fish and Wildlife Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program 1807 13th Street, Suite 202 Sacramento, CA 95811 and California Native Plant Society 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento, CA 95816 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this project was provided by: California Energy Commission US Bureau of Land Management California Wildlife Conservation Board California Department of Fish and Wildlife Personnel involved in developing the methodology and implementing this project included: Aerial Information Systems: Lisa Cotterman, Mark Fox, John Fulton, Arin Glass, Anne Hepburn, Ben Johnson, Debbie Johnson, John Menke, Lisa Morse, Mike Nelson, Ed Reyes, Janet Reyes, Patrick Yiu California Department of Fish and Wildlife: Diana Hickson, Todd Keeler‐Wolf, Anne Klein, Aicha Ougzin, Rosalie Yacoub California -

Geographic Distribution of Hantaviruses Associated with Neotomine and Sigmodontine Rodents, Mexico Mary L

Geographic Distribution of Hantaviruses Associated with Neotomine and Sigmodontine Rodents, Mexico Mary L. Milazzo,1 Maria N.B. Cajimat,1 Hannah E. Romo, Jose G. Estrada-Franco, L. Ignacio Iñiguez-Dávalos, Robert D. Bradley, and Charles F. Fulhorst To increase our knowledge of the geographic on the North American continent are Bayou virus, Black distribution of hantaviruses associated with neotomine or Creek Canal virus (BCCV), Choclo virus (CHOV), New sigmodontine rodents in Mexico, we tested 876 cricetid York virus, and Sin Nombre virus (SNV) (3–7). Other rodents captured in 18 Mexican states (representing at hantaviruses that are principally associated with neotomine least 44 species in the subfamily Neotominae and 10 or North American sigmodontine rodents include Carrizal species in the subfamily Sigmodontinae) for anti-hantavirus virus (CARV), Catacamas virus, El Moro Canyon virus IgG. We found antibodies against hantavirus in 35 (4.0%) rodents. Nucleotide sequence data from 5 antibody-positive (ELMCV), Huitzilac virus (HUIV), Limestone Canyon rodents indicated that Sin Nombre virus (the major cause of virus (LSCV), Montano virus (MTNV), Muleshoe virus hantavirus pulmonary syndrome [HPS] in the United States) (MULV), Playa de Oro virus, and Rio Segundo virus is enzootic in the Mexican states of Nuevo León, San Luis (RIOSV) (8–14). Potosí, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz. However, HPS has not Specifi c rodents (usually 1 or 2 closely related been reported from these states, which suggests that in species) are the principal hosts of the hantaviruses, northeastern Mexico, HPS has been confused with other for which natural host relationships have been well rapidly progressive, life-threatening respiratory diseases. -

Cliff Chipmunk Tamias Dorsalis

Wyoming Species Account Cliff Chipmunk Tamias dorsalis REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: No special status USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Nongame Wildlife CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: No special status WGFD: NSS3 (Bb), Tier II WYNDD: G5, S1 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS Cliff Chipmunk (Tamias dorsalis) has no additional regulatory status or conservation rank considerations beyond those listed above. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: There are six recognized subspecies of Cliff Chipmunk, but only T. d. utahensis is found in Wyoming 1-5. Global chipmunk taxonomy remains disputed, with some arguing for three separate genera (i.e., Neotamias, Tamias, and Eutamias) 6-8, while others support the recognition of a single genus (i.e., Tamias) 9. Cliff Chipmunk was briefly referred to as N. dorsalis 10 but has recently been returned to the currently recognized genus Tamias, along with all other North American chipmunk species 11. Description: Cliff Chipmunk is a medium-large chipmunk that can be easily identified in the field by its mostly smoke gray upperparts, indistinct dorsal stripes (with the exception of one dark stripe along the spine), brown facial stripes, long bushy tail, stocky body, short legs, and white underbelly 2-5. This species exhibits sexual size dimorphism, with females averaging larger than males 2, 3. Adults weigh between 55–90 g with total length ranging from 208–240 mm 4. Tail, hind foot, and ear length range from 81–110 mm, 30–33 mm, and 17–21 mm, respectively 4. Within its Wyoming distribution, Cliff Chipmunk is easy to distinguish from Yellow-pine Chipmunk (T. -

Plant and Rodent Communities of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument

Plant and rodent communities of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Warren, Peter Lynd Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 16:51:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/566520 PLANT AND RODENT COMMUNITIES OF ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL.MONUMENT by Peter Lynd Warren A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 9 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Interest and the Panamint Shoshone (E.G., Voegelin 1938; Zigmond 1938; and Kelly 1934)

109 VyI. NOTES ON BOUNDARIES AND CULTURE OF THE PANAMINT SHOSHONE AND OWENS VALLEY PAIUTE * Gordon L. Grosscup Boundary of the Panamint The Panamint Shoshone, also referred to as the Panamint, Koso (Coso) and Shoshone of eastern California, lived in that portion of the Basin and Range Province which extends from the Sierra Nevadas on the west to the Amargosa Desert of eastern Nevada on the east, and from Owens Valley and Fish Lake Valley in the north to an ill- defined boundary in the south shared with Southern Paiute groups. These boundaries will be discussed below. Previous attempts to define the Panamint Shoshone boundary have been made by Kroeber (1925), Steward (1933, 1937, 1938, 1939 and 1941) and Driver (1937). Others, who have worked with some of the groups which border the Panamint Shoshone, have something to say about the common boundary between the group of their special interest and the Panamint Shoshone (e.g., Voegelin 1938; Zigmond 1938; and Kelly 1934). Kroeber (1925: 589-560) wrote: "The territory of the westernmost member of this group [the Shoshone], our Koso, who form as it were the head of a serpent that curves across the map for 1, 500 miles, is one of the largest of any Californian people. It was also perhaps the most thinly populated, and one of the least defined. If there were boundaries, they are not known. To the west the crest of the Sierra has been assumed as the limit of the Koso toward the Tubatulabal. On the north were the eastern Mono of Owens River. -

SOUTHEASTERN INYO Tt;OUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE SUPERPOSED MESOZOIC DEFOR~~TIONS~ }) SOUTHEASTERN INYO tt;OUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of 14aster of Science in Geology by Michael Robert Werner Janu(l.ry 3 i 979 The Thesis of Michael Robert Werner is approved: Or. L. Ehltg}rCSULA) Ca 1i forn i a State Un i vers ·j ty, Northridge ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ~1y respectful thanks to George Dunn£ for suggesting this study and for his helpful comments throughoutthe investigation. I am grateful also to Rick Miller and Perry Eh1ig VJho reviewed the manuscript in various stages of preparation. !'r1y special thanks to my parents for theit~ emotiona1 and 1ogistica·i support, and to Diane Evans who typed the first draft. Calvin Stevens and Duane Cavit, California State University~ San Jose, provided valuable information on stratigraphy; and Jean Ju11iand, geologist of the Desert Plan Staff, BLM, Riverside, made available aerial photographs of the study area.· The Department of Geosciences, California State University. Northridge pi·ovided computer time and financial support. Terry Dunn, CSUN, typed the fina1 manuscript. iii TAaLE OF CONTENTS p~~ ACKNOl~LEDGEHENTS. .. 111 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . vi ABSTRACT ... vii. INTRODUCTION 1 METHOD • 3 ROCK UNITS •. 5 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY . 5 Perdido Formation 7 Rest Spring Shale . .. 3 Keeler Canyon Formation 10 Owens Vulley Formation 14 MESOZOIC INTRUSIVE ROCKS . 16 • Hunter Mountain batholith 16 Andes 'ite porphyry di kas 17 CENOZOIC UNITS . 18 STRUCTURJl.L GEOLOGY 19 FOLDS • ~ . 19 Introduction 19 Folds in the Nelson Range . 21 F., - The San Lucas Canyon syncline 2"1 j r2 - Northwest-trending folds 31 Folds aajacent to the Hunter Mountain batholith 37 Folds in the Southeastern Inyo r'Jounta·ins 43 Southwest-trending folds 43 Northwest-trending folds . -

Mammal Watching in Northern Mexico Vladimir Dinets

Mammal watching in Northern Mexico Vladimir Dinets Seldom visited by mammal watchers, Northern Mexico is a fascinating part of the world with a diverse mammal fauna. In addition to its many endemics, many North American species are easier to see here than in USA, while some tropical ones can be seen in unusual habitats. I travelled there a lot (having lived just across the border for a few years), but only managed to visit a small fraction of the number of places worth exploring. Many generations of mammologists from USA and Mexico have worked there, but the knowledge of local mammals is still a bit sketchy, and new discoveries will certainly be made. All information below is from my trips in 2003-2005. The main roads are better and less traffic-choked than in other parts of the country, but the distances are greater, so any traveler should be mindful of fuel (expensive) and highway tolls (sometimes ridiculously high). In theory, toll roads (carretera quota) should be paralleled by free roads (carretera libre), but this isn’t always the case. Free roads are often narrow, winding, and full of traffic, but sometimes they are good for night drives (toll roads never are). All guidebooks to Mexico I’ve ever seen insist that driving at night is so dangerous, you might as well just kill yourself in advance to avoid the horror. In my experience, driving at night is usually safer, because there is less traffic, you see the headlights of upcoming cars before making the turn, and other drivers blink their lights to warn you of livestock on the road ahead. -

Inventory of Mammals at Walnut Canyon, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater National Monuments

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Inventory of Mammals at Walnut Canyon, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater National Monuments Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR–2009/278 ON THE COVER: Top: Wupatki National Monument; bottom left: bobcat (Lynx rufus); bottom right: Wupatki pocket mouse (Perogna- thus amplus cineris) at Wupatki National Monument. Photos courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey/Charles Drost. Inventory of Mammals at Walnut Canyon, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater National Monuments Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2009/278 Author Charles Drost U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Editing and Design Jean Palumbo National Park Service, Southern Colorado Plateau Network Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, Arizona December 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

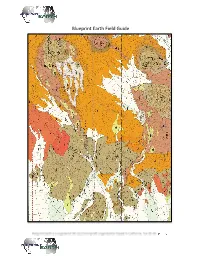

Blueprint Earth Field Guide

Blueprint Earth Field Guide Plants Note that this list is not comprehensive. If you are uncertain of the identification you’ve made of a particular plant, take a picture and a voucher (when possible) and discuss your observations with the Supervisory Scientist team. Trees & Bushes Joshua tree - Yucca brevifolia Parry saltbush - Atriplex parryi Mojave sage - Salvia pachyphylla Creosote bush - Larrea tridentata Mojave yucca - Yucca schidigera Chaparral yucca - Yucca whipplei Torr. Desert holly - A. hymenelytra Torr. Manzanita - Arctostaphylos Adans. Cacti Barrel cactus - Ferocactus cylindraceus var. Jumping cholla - Cylindropuntia bigelovii Engelm. lecontei Foxtail cactus - Escobaria vivipara var. alversonii Silver cholla - Opuntia echinocarpa var. echinocarpa Pencil cholla - Opuntia ramosissima Cottontop cactus - Echinocactus polycephalus Hedgehog cactus - Echinocereus engelmanii var. Mojave mound cactus - Echinocereeus chrysocentrus triglochiderus var. mojavensis Beavertail cactus - Opuntia basilaris Grasses Indian Rice Grass - Oryzopsis hymenoides Bush Muhly - Muhlenbergia porteri Fluff Grass - Erioneuron pulchella Red Brome - Bromus rubens Desert Needle - Stipa speciosa Big Galleta – Hilaria rigida Flowers Wooly Amsonia Chuparosa Amsonia tomentosa Justicia californica Brittlebush Encelia farinosa Chia Salvia columbariae Sacred Datura Desert Calico Datura wrightii Loeseliastrum matthewsii Bigelow Coreopsis Desert five-spot Coreopsis bigelovii Eremalche rotundifolia - Desert Chicory Rafinesquia Desert Lupine neomexicana Desert Larkspur -

A Longitudinal Study of Sin Nombre Virus Prevalence in Rodents, Southeastern Arizona

Hantavirus A Longitudinal Study of Sin Nombre Virus Prevalence in Rodents, Southeastern Arizona Amy J. Kuenzi, Michael L. Morrison, Don E. Swann, Paul C. Hardy, and Giselle T. Downard University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA We determined the prevalence of Sin Nombre virus antibodies in small mammals in southeastern Arizona. Of 1,234 rodents (from 13 species) captured each month from May through December 1995, only mice in the genus Peromyscus were seropositive. Antibody prevalence was 14.3% in 21 white-footed mice (P. leucopus), 13.3% in 98 brush mice (P. boylii), 0.8% in 118 cactus mice (P. eremicus), and 0% in 2 deer mice (P. maniculatus). Most antibody-positive mice were adult male Peromyscus captured close to one another early in the study. Population dynamics of brush mice suggest a correlation between population size and hantavirus-antibody prevalence. We examined the role of rodent species as success, and webs 2, 3, and 4 were operated from natural reservoirs for hantaviruses in southeast- May 1995 through December 1997. ern Arizona to identify the species infected with From May 1995 through September 1996, hantavirus, describe the characteristics of webs 1 and 4 were considered controls. Captured infected animals, and assess temporal and mice from these webs were identified, marked, intraspecific variation in infection rates. weighed, and measured, but not bled. Beginning in November 1996, we began collecting blood Trapping Procedures samples from mice on web 4. The bleeding process Beginning in May 1995, we established four had little effect on survival (1). The methods for permanent trapping webs on the Santa Rita obtaining blood samples and the serologic testing Experimental Range in the Santa Rita Moun- of samples for hantavirus antibodies are tains of southeastern Arizona (Pima County).