Lighting up the Arena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S/N Company Name Address Licence Number

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER REPAIRS AND MAINTENANCE S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENCE NUMBER 1 Telecare Wireless Ltd 13, Amodu Ojikutu Street, V/I, Lagos CL/R&M/001/07 2 Lintech TelecommunicationsSolution Nig Ltd 18am Temple Road, Ikoyi PMB 40014, Falomo, Lagos CL/R&M/002/07 3 Juvs Acme Network Ltd Plot 53, Agege Motor Road, Ladipo Opp FRCN - GRA) Ikeja Lagos CL/R&M/003/07 4 Stepping Forth TechnologyConcepts Ltd Shop A5, Zuma Mall, 20 Ndola Crescent, Wuse Zone5, Abuja CL/R&M/004/07 5 Or - be -com Nig Ltd 21/23, Flat 7, Block 7, Taslim Elias Close, V/I, Lagos CL/R&M/005/07 6 Phoneport Services Centre Ltd No 25, Kampala Street, Wuse II, Abuja CL/R&M/006/07 7 Camtec Nig Ltd 201B, Corporation Drive Dolphin, Estate Ikoyi, Lagos CL/R&M/007/07 8 Telecom Eng Tools Ltd Suite 18, Gwamna Complex, N3, Kachia Road, Kaduna CL/R&M/008/07 9 Wireless Point Communications& Technologies Ltd No 51 Constitution Avenue, Gaduwa Housing EstateAbuja CL/R&M/009/07 10 Qrec Nig Ltd No 9, New Era Road, Iyana - Ipaja, Lagos CL/R&M/010/07 11 Barotech Nig Ltd 20, Mbonu Street, D - Line Port Harcourt Rivers State CL/R&M/001/08 12 BT Technologies Ltd 6th Floor Bookshop House 50 -52, Broad Street, Lagos CL/R&M/002/08 13 Spar Aerospace Nig Ltd 3A Aja Nwachukwu Close, Ikoyi Lagos CL/R&M/003/08 14 Smartway Technologies Ltd 155, Olojo Drive, Ojo Lagos CL/R&M/004/08 15 Steve Power - Mart Ltd 11, Olatubosun Street, Sonibare Estate, MarylandLagos CL/R&M/005/08 16 Dagbs Nig Ltd Suite 101, Dolphin Plaza Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi, Lagos CL/R&M/006/08 17 Chuks Telecoms GlobalResources Ltd 24 Kirikiri Rd, 2nd Floor, Flat2, Olodi Apapa, Lagos CL/R&M/007/08 18 Peak Mark Procurement Ltd 28, Osinowo Street, Gbagada, Lagos CL/R&M/008/08 19 Protean Global Nig Ltd 234A, Muki Okunola Street, V/I, Lagos CL/R&M/009/08 1 CLASS LICENCE REGISTER REPAIRS AND MAINTENANCE 20 Western Development Co. -

Heial Gazette

gx?heial© Gazette No. 87 LAGOS -*4th November, 1965 CONTENTS Page : Page Movements of Officers 1802-11 Loss of Assessment of Duty Book -¢ 1833 Applications for Registration of Trade Unions - 1811 Loss of Hackney Carriage Driver’s Badges... 1833 Probate Notices 1811-12 Loss of Revenue Collectors Receipt .. 1834 Notice of Proposal to declare a Pioneer \ Recovery of Lost Government Marine Industry 1812 Warrants . - 1834 Granting of a Pioneer Certificate — 1813 Loss of Specific Import Licences i. « 1834 i Application to eonstruct a Leat 1813 Loss of Local Purchase Orders 1834 Application for an Oil Pipeline Licence 1813-4 Admission into Queen’s College, 1966 1835 Appointments of Notary Public 1814-5 Admission into King’s College, 1966 - 1836 Addition to the List of Notaries Public 1815 Tenders 1837-8 Corrigenda 1815 Vacancies 1838-45 Nigeria Trade Journal Vol. 13 No. 3.. 1815 Competition of Entry into the Administrative and Special Departmental Classes of the Release of Two Values of the New Definitive Eastern Nigeria Public Service, 1966 1845-6 Postage Stamps . .. ws 1816 _ Adult Education Evening Classes, 1966 . - 1847-8 Transfer of Control—OporomaPostal Agency 1816 : : Federal School of Science, Lagos—Evening : Prize Draw—National Premium Bonds 1816-7 Classes, 1966 + . 1848 Board of Customs and Excise—Customs and Board of Customs and Excise—Sale of " 1849-52 Excise Notice No. 44 -- 1818-20 Goods oe .. .e Re Lats Treasury Returns Nos, 2, 3, 3.1, 3.2, and 4 1821-5 Official Gazette—Renewal Notice 1. 1853" Federal Land Registry—Registration of Titles .- - os 1826-33 INDEX TO Lecat Notice in SUPPLEMENT Appointmentof Member of National Labour L.N. -

TECHNICAL REPORT Issue 1, No

TECHNICAL REPORT Issue 1, No. 1, March, 2019 REPORT ON THE NEED TO RATIONALIZE AND RESTRUCTURE FEDERAL MINISTRIES, DEPARTMENTS AND AGENCIES (MDAs) Edoba B. Omoregie, Tonye C. Jaja, Samuel Oguche and Usman Ibrahim Department of Legislative Support Services Background/Rationale Worried by the non-implementation of the Steve Oronsaye Report recommending the rationalisation and restructuring of Federal Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs), the National Institute for Legislative and Democratic Studies constituted a four-man Technical Committee to study the Oronsaye Report vis-à- vis existing agencies, and make appropriate recommendations on the way forward, including drafting proposed legislations (Bills) in practical response to specific issues raised, where necessary. From a financial, administrative and legal point-of-view, it is now a global standard practice of modern legislatures around the world to undertake Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) and Legislative Impact Analysis (LIA), even if it is a “rudimentary cost-benefit analysis”1 of proposed legislation. The primary purpose of such RIA and LIA, or cost-benefit analysis of proposed legislation is to enable legislators make an informed decision based on concrete evidence that a proposed legislation is beneficial for the greater number of citizens. In Nigeria, as evident from the 2011 Steve Oronsaye Report, the failure to undertake RIA and LIA/rudimentary cost-benefit analysis of proposed legislation (especially for those category of legislation that seeks to establish statutory -

Republicof Nigeria “Official, Gazette

- Republicof Nigeria “Official, Gazette No.77 ° LAGOS- 4th: August, 1966 Vol. 53 - CONTENTS ‘ Page , Page Movements of Officers 1502-9 Examination in Law, General Orders, Finan- 8 cial Instructions, Police Orders and Instruc- Probate Notice * 4509 — tions and Practical Police Work, December - & 1966 .. 1518 bee 1509 Appointment e499: of Notary Public > Loss of Local Purchase Orders . 1518-9 * Addition to the List of Notaries Public . 1509 _ Loss ofReceipt Voucher os 1519 5 - : . Application for Registration of Trade Unions 1510 {os of Last PayCertificate 1519 ~. Appointment of Directors of the Central: - Lossof Original Local Purchase Order soe y, 1519 ¢ Bank of Nigeria s .- no 1510 - ' Loss of Official Receipts 1519 - Revocation of the Appointment of Chief Saba co as a Memberofthé Committee of Chiefs 1510 Central Bank of Nigeria—Return of Assets - and Liabilities as at Close of Business on , . -4 ] Addendum—Law Officers in the Capital . sth July, 1966 me . 1519 ' Territory Le Tee ve 1510 tees PL. .1520-4 Notice of Removal from the Register of Vacancies 7 7 2 1524-31 Companies 1S1i : . Lands Requiredforthe Serviceof the National ; Board a Customs and Excise—Sale of 1531.2 Military Government 3 > 4511 gods . ee “ * Appointment of Licensed Buying Agents “oo. 1512 ° : Lagos Land Registry—First Registration of . INDEX TO LeGaL NOTICES IN SUPPLEMENT + Titles1 ere ee ett. 1512-18No,. * “Short Title Page. Afoigwe Rural Call Office—Openingof. © 1518 ~° 68 MilitaryAdministrator of the Capital . Territory (Delegation of Powers) Zike AvenuePostal Agency—Opening of 1518 Notice. 1966 .. B343 No. 77, Vol. 53 1502 OFFICIAL GAZETTE 5 Government. Notsce No. 1432 STAFF CHANGES ‘NEWW APPOINTMENTS AND OTHER 2 The following are nitified for general intormation :— NEW APPOINTMENTS Appointment Date of Date of Depariment Name -Ippointment Arrival Stenographer, Grade II 3-12-62 Administration Nnoromele, P. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.B / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

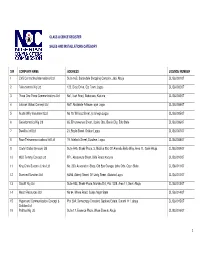

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Lagos State Poctket Factfinder

HISTORY Before the creation of the States in 1967, the identity of Lagos was restricted to the Lagos Island of Eko (Bini word for war camp). The first settlers in Eko were the Aworis, who were mostly hunters and fishermen. They had migrated from Ile-Ife by stages to the coast at Ebute- Metta. The Aworis were later reinforced by a band of Benin warriors and joined by other Yoruba elements who settled on the mainland for a while till the danger of an attack by the warring tribes plaguing Yorubaland drove them to seek the security of the nearest island, Iddo, from where they spread to Eko. By 1851 after the abolition of the slave trade, there was a great attraction to Lagos by the repatriates. First were the Saro, mainly freed Yoruba captives and their descendants who, having been set ashore in Sierra Leone, responded to the pull of their homeland, and returned in successive waves to Lagos. Having had the privilege of Western education and christianity, they made remarkable contributions to education and the rapid modernisation of Lagos. They were granted land to settle in the Olowogbowo and Breadfruit areas of the island. The Brazilian returnees, the Aguda, also started arriving in Lagos in the mid-19th century and brought with them the skills they had acquired in Brazil. Most of them were master-builders, carpenters and masons, and gave the distinct charaterisitics of Brazilian architecture to their residential buildings at Bamgbose and Campos Square areas which form a large proportion of architectural richness of the city. -

Nigeria Cial Gazette

"ta. 3 epublic of |Nigeria cial Gazette No. 79° LAGOS-3rd October, 1963 Vol. 50 CONTENTS * Page , f — Page Appointment of Permanent Secretary 1534 Monthly Palm Kernels and Palm Oil Pur- Movements of Officers . i 53 chases in the Federation of Nigeria. - 1552-3 | Federal Government Scholarships, 1963— Royal Nigerian : — i ve’ we «11540 > oyal Nigerian Navy- Promotions il Undergraduates and Technical Studies— . Probate Notices se een .- 1540-2 Supplementary Awards 1553-4 Appointmentof a Notary Public 1542 Federal Government Scholarships—Post- . Graduate Awards 1963 .. oe 1554 Addition to the List of Notaries Public 1542 . Registration of a Notary Public - oe “4 542 Federal Government Scholarships—Secondary Application for ¢ ImportDut is42 School Awards for Federal Territory of pplication for Repayment of Import Duties - Lagos .. 1854 Granting of a Pioneer Certificate oe 7 : 1543 . Federal Government Scholarships—Secondary Appointment of an Appeal Commissioner .. .:1543 r School Award for Niger Delia Special Area 1554-5 . 1555- Resignation of a Memberof Scrutineer Com- . * “neers 1555-8 mittee for Kano Area os -» 1543” Vacancies’ . 1558-60 Revocation of Mining Lease Nos. ML. 12605 . and ML. 14117. 1543 . Board of Customs and Excise Notices _ 1561-2 Land required for the Services of the° Federal| Official Gazettes - Renewal Notice 1563 Government . 543-4 Public Lands Acquistion—Withdrawalof : INDEX To LEGAL Notices IN SUPPLEMENT Government Notice. .. - -"4544 "Application for an Oil Pipeline Licence...sau LN. Na. Short Title Page 125 National Premium Bonds Regula- Federal Land Registry—Applications#forFirst Registration .. -1pss-9 tions, 1963 .. B451 Loss of Exhausted Revenue Collector’s 126 Savings Certificates Regulations, 1963 B458 Receipt Book, Local Purchase Orders, etc. -

Nigerian Film Industry in the Mirror of African Movie Academy Awards (AMAA)

Nigerian Film Industry in the Mirror of African Movie Academy Awards (AMAA) (2016) Journal of Arts and Humanities 5.9: Pp 75-83. http://www.theartsjournal.org (ISSN: 2167-9045). By Stanislaus Iyorza (Ph.D), Department of Theatre and Media Studies University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. [email protected] [email protected] +2347064903578 ABSTRACT Worried by the drastic decline in the quality of content of Nigerian movies as evaluated by critics, this paper analyzes the evaluation of Nigerian movies by the African Movie Academy Awards (AMAA) between 2006 and 2016. The objective is to review the decisions of the AMAA jury and to present the academy’s position on the prospects and deficiencies of the Nigerian Movie industry. The paper employs analytical research approach using both primary and secondary sources to explore assessed contents of the Nollywood movies and how far the industry has fared in the mirror of a renowned African movie assessor like AMAA. This paper assembles data of the awards of AMAA since inception and graphically presents the data. Findings reveal a sharp drop in quality of content of Nigerian movies over the years with a hope of an upsurge as adjudged by AMAA since 2006. The study recommends the private sector’s all round support to Nollywood and the federal government’s training or retraining of filmmakers as well as sustained funding for the steady development of the Nigerian movie industry. Key words: AMAA, Evaluation, Film, Jury, Nollywood. 1 Introduction Nigeria is currently faced with a myriad of issues including a drastic recession in the economy, the political arena and the art industry. -

Agenda Setting Theory and the Influence of Celebrity Endorsement on Brand Attitude of Middle Class Consumers in Lagos, Nigeria

AGENDA SETTING THEORY AND THE INFLUENCE OF CELEBRITY ENDORSEMENT ON BRAND ATTITUDE OF MIDDLE CLASS CONSUMERS IN LAGOS, NIGERIA BY AKASHORO GANIYU OLALEKAN MATRIC. NO: 959009055 B. Sc. (Mass Comm., UNILAG), M. Sc. (Mass Comm., UNILAG) Department of Mass Communication, School of Postgraduate Studies, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria May, 2013 1 AGENDA SETTING THEORY AND THE INFLUENCE OF CELEBRITY ENDORSEMENT ON BRAND ATTITUDE OF MIDDLE CLASS CONSUMERS IN LAGOS, NIGERA BY AKASHORO GANIYU OLALEKAN MATRIC. NO: 959009055 B. Sc. (Mass Comm., UNILAG), M. Sc. (Mass Comm., UNILAG) Department of Mass Communication, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) IN MASS COMMUNICATION MAY, 2013 2 DECLARATION I declare that this Ph.D thesis was written by me. I also declare that this thesis is the result of painstaking efforts. It is original and it is not copied. ………………………………………………………………. Ganiyu Olalekan Akashoro (Mr) Department of Mass Communication Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Lagos, Lagos State, Nigeria. [email protected] [email protected] Date:………………………………… 3 CERTIFICATION This Ph. D thesis has been examined and found acceptable in meeting the requirements of the postgraduate School of the University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos State, Nigeria. …………………………………… Dr. Abayomi C. Daramola Supervisor ………………………………………….. Dr. Abigail O. Ogwezzy-Ndisika Supervisor …………………………………. Dr Victor Ayedun-Aluma Departmental PG Coordinator …………………………………… …………………… Dr. Abayomi C. Daramola Date. Acting Head of Department 4 DEDICATION This work is dedicated first and foremost to Allah, most gracious, most merciful (God Almighty), the only source of true knowledge, understanding, as well as the bestower of true and authentic wisdom. -

Reviewed Paper Assessment of Metropolitan

% reviewed paper Assessment of Metropolitan Urban Forms and City Geo-spatial Configurations using Green Infrastructure Framework: The Case Study of Lagos Island, Lagos State, Nigeria Adesina John A., Timothy Michael A., Akintaro Emmanuel A. (Adesina John A., Department of Architecture, University of Lagos, Lagos, [email protected]) (Timothy Michael A., Department of Surveying &Geo-informatics, Bells University of Technology, Ota, Ogun State, [email protected]) (Akintaro Emmanuel A., Department of Architecture, Federal University of Technology Akure, Ondo State, [email protected]) 1 ABSTRACT For over three decades, the economic and commercial activities of both local and foreign organizations, firms, industries and institutions have been moving to the Lagos Island in search for a reputable business atmosphere and this has led to the emergence of vertical urbanizations of the area thereby turning it into a foremost Central Business District (CBD). The Lagos metropolis is the economic hub of West Africa and the Lagos Island has the bulk of the economic activities. Most of the ill-controlled infrastructural developments are along the major streets and the Island districts are supposed to have certain spatial configurations expected of a metropolitan city like Lagos. The basic urban form design policies and theories had been neglected long time ago thereby making the streets faced with chaotic smart growths, worrisome urban resilience and harsh biophilic architecture with little or no consideration to green landscapes. This study is situated upon the Urban Morphological Theory which investigates the relationships between urban design spatial configurations, landscape and ecological urbanism and some other green city conceptual frameworks. Scholars in the field of landscape urbanism had made divergent or opposed theoretical, conceptual and methodological choices, opportunities in the metamorphosis of a city forms and streetscapes. -

The Hilltop 3-4-1977

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University The iH lltop: 1970-80 The iH lltop Digital Archive 3-4-1977 The iH lltop 3-4-1977 Hilltop Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_197080 Recommended Citation Staff, Hilltop, "The iH lltop 3-4-1977" (1977). The Hilltop: 1970-80. 180. http://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_197080/180 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The iH lltop Digital Archive at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH lltop: 1970-80 by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ' Hilltop Highlights •' Bar Preparatory COurse ..... p3 fl(J f/1111 ,e. ' Editorial .On FEST AC .. ..... p4 11 i1hr111/ , 1 clr'lll.J/lCI" Mak e Someone Happy .. .... p7 .. Minnie's Stay In Love ....... p8 Bison And Morgan State .. plO • "THE VOICE OF THE HOWARD COMMUNITY" CIAA Tournament ............ pl l Vol. 59, No. 20 Howard University, Washington, D.C. 20059 4 March 1977 • Universi Ho' war Jordan Emphasizes Importance of Young Talks About Uniqueness of Howard I Alumni Support For HU In Future and Interdependence · Between Na,!j.Qns J ' By Venola Rolle 11la c ed t1rne sp ent w i th a IC'ading role in world affairs' ' By Katherine Barrett 111e r1t 1n U n 1Vl' rs1t y ari d co rn f ralerr1 it1 es 1n tfiat catego ry, d would be a9versely. affected, I· Hilltop Slaffwrill'r Hilltop Staffwriler mun1ty 0 ervl CC' lie rt'cc1veLl J)art uf the audien ce c heered Young also stressed the in b tJ!h his B.S.