Adam and Eve: Shameless First Couple of the Ghent Altarpiece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Jan Van Eyck, New York 1980, Pp

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/29771 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-24 and may be subject to change. 208 Book reviews werp, 70 from Brussels and around 100 from Haarlem. Maryan Ainsworth and Maximiliaan Martens evidently cannot agree on Christus’s origins. Martens (p. 15) believes that the Brabant Baerle is the more likely contender (even the unusual surname is commoner there), while Ainsworth (p. 55) would prefer him Maryan W. Ainsworth, with contributions by Maximi- to come from the Baerle near Ghent, and he would then step liaan P.J. Martens, Petrus Christus: Renaissance mas effortlessly into a “post-Eyckian workshop.” What is perhaps ter of Bruges, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) more important than the true birthplace (even though it might 1994* provide new points of reference), and certainly more so than the pernicious attempts to classify the young Petrus Christus as either “Dutch” or “early Flemish,” are the efforts to establish “Far fewer authors have written about Petrus Christus and his an independent position for this master, whose fortune and fate art since 1937 than on the van Eycks. Bazin studied one aspect it was to be literally forced to work in the shadow of Jan van of his art, Schöne proposed a new catalogue of his works, in an Eyck, the undisputed “founding father” of northern Renais appendix to his book on Dieric Bouts. -

On Making a Film of the MYSTIC LAMB by Jan Van Eyck

ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2012 Figure 1 The Mystic Lamb (1432), Jan van Eyck. Closed Wings. On Making a film of THE MYSTIC LAMB by Jan van Eyck Jules Cashford Accompanying sample clip of the Annunciation panel, closed wings middle register from DVD is available free on YouTube here. Full Length DVDs are also available. Details at the end of this article. The images in this paper are strictly for educational use and are protected by United States copyright laws. Unauthorized use will result in criminal and civil penalties. 1 ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2012 Figure 2 The Mystic Lamb (1432), Jan van Eyck. Open Wings. The Mystic Lamb by Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) The Mystic Lamb (1432), or the Ghent Altarpiece, in St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, is one of the most magnificent paintings of the Early Northern Renais- sance. It is an immense triptych, 5 meters long and 3 meters wide, and was origi- nally opened only on feast days, when many people and painters would make a pilgrimage to be present at the sacred ritual. They could see – when the wings were closed – the annunciation of the Angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary, which The images in this paper are strictly for educational use and are protected by United States copyright laws. Unauthorized use will result in criminal and civil penalties. 2 ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2012 they knew as the Mystery of the Incarnation. But when the wings were opened they would witness and themselves participate in the revelation of the new order: the Lamb of God, the story of Christendom, and the redemption of the World. -

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING Part One

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING part one Early Netherlandish painting is the work of artists, sometimes known as the Flemish Primitives, active in the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands during the 15th- and 16th-century Northern Renaissance, especially in the flourishing cities of Bruges, Ghent, Mechelen, Leuven, Tounai and Brussels, all in present-day Belgium. The period begins approximately with Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck in the 1420s and lasts at least until the death of Gerard David in 1523, although many scholars extend it to the start of the Dutch Revolt in 1566 or 1568. Early Netherlandish painting coincides with the Early and High Italian Renaissance but the early period (until about 1500) is seen as an independent artistic evolution, separate from the Renaissance humanism that characterised developments in Italy; although beginning in the 1490s as increasing numbers of Netherlandish and other Northern painters traveled to Italy, Renaissance ideals and painting styles were incorporated into northern painting. As a result, Early Netherlandish painters are often categorised as belonging to both the Northern Renaissance and the Late or International Gothic. Robert Campin (c. 1375 – 1444), now usually identified with the Master of Flémalle (earlier the Master of the Merode Triptych), was the first great master of Flemish and Early Netherlandish painting. Campin's identity and the attribution of the paintings in both the "Campin" and "Master of Flémalle" groupings have been a matter of controversy for decades. Campin was highly successful during his lifetime, and thus his activities are relatively well documented, but he did not sign or date his works, and none can be confidently connected with him. -

96 HUGH HUDSON the Chronograms in the Inscription of Jan Van Eyck's

HUGH HUDSON The chronograms in the inscription of Jan van Eyck's Portrait of Jan de Leeuw* Although numerous authors have believed that Jan van Eyck included chronograms in the Ghent altarpiece quatrain (Ghent, Saint Bavo's Cathedral) and the inscription of his Portrait of Jan de Leeuw (Fig. I ) (Vienna, Kllnsthistorisches Museum), doubts have been expressed about whether the former was actually composed by Van Eyck and whether the latter even contains chronograms. Thus, there has been some un- certainty regarding whether Van Eyck used chronograms at all. It seems to have es- caped notice that there is unequivocal evidence in the disposition of the highlights on the letters of the Portrait ofJan dueLeeuw that Van Eyck did include two chrono- grams therein. Chronograms are inscriptions in which a year is encoded in the text through the se- lection of words containing letters with Roman numeral values adding up to the year to be signified. The text alludes to an event in that year. In a nineteenth cen- tury collection of over five thousand chronograms James Hilton wrote that the use of chronograms in Western languages dated to the fourteenth century. Hilton also noted that in Flemish chronograms certain variations in the use of Roman numer- als occurred, with the letter "w" capable of being read as two "v"s side by side and given a value of ten (Van Eyck painted the "w"s in the Portrait ofjan Leeuu' as pairs of overlapping "v"s), the letter "Y" capable of being given a value of two (in Hubert and Jan van Eyck's Ghent altarpiece the letter "Y" was painted on the ban- derole behind Zachariah as a long vertical stroke on the left joined to a short verti- " cal stroke on the right by a diagonal stroke rising to the right) and the letter "m" was sometimes not given any value at all. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 9-Apr-2010 I, Edward Silberstein , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in Art History It is entitled: And Moses Smote the Rock: The Reemergence of Water in Landscape Painting In Late Medieval and Renaissance Western Europe Student Signature: Edward Silberstein This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Kristi Ann Nelson, PhD Kristi Ann Nelson, PhD Kimberly Paice, PhD Kimberly Paice, PhD Mikiko Hirayama, PhD Mikiko Hirayama, PhD 9/28/2010 1,111 And Moses Smote the Rock: The Reemergence of Water in Landscape Painting in Late Medieval and Renaissance Western Europe A thesis submitted to the Graduate School Of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In the Department of Art History Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning Master of Arts in Art History By Edward B. Silberstein B.A. magna cum laude Yale College June 1958 M.D. Harvard medical School June 1962 Committee Chair: Kristi Nelson, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis undertook the analysis of the realistic painting of water within the history of art to examine its evolution over four millennia. This required a detailed discussion of what realism has meant, especially over the centuries of the second millennium C.E. Then the trends in the painting of water from Cretan and Mycenaean eras, through Hellenistic and Roman landscape, to the limited depiction of landscape in the first millennium of the Common Era, and into the late medieval era and the Renaissance were traced, including a discussion of the theological and philosophical background which led artists to return to their attempts at producing an idealized realism in their illuminations and paintings. -

Beeld Van De Stad

Beeld van de Stad Beeld van de Stad Picturale voorstellingen van stedelijkheid in de laatmiddeleeuwse Nederlanden Jelle De Rock Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van doctor in de geschiedenis aan de Universiteit Antwerpen Departement Geschiedenis Antwerpen, 2011 Promotor : Prof. Dr. P. Stabel Copromotor : Prof. Dr. M.P.J. Martens Prof. Dr. M. Boone Coverillustratie : Navolger Dirk Bouts, Heilige Drievuldigheidstriptiek , 1475-1500, Sint- Servatiuskerk, Berg (Kampenhout) - © KIK-IRPA, Brussel INHOUDSTAFEL VOORWOORD 9 INLEIDING 11 1. Picturale stadsrepresentaties in het wetenschappelijk onderzoek 12 1.1. De pictorial turn : 15 1.2. De spatial turn 18 1.3. Cognitieve geografie 19 2. Een focus op de paneelschilderkunst 21 2.1. Ars Nova: tussen hof- en burgerkunst 22 2.2. Corpus, methode en beperkingen 24 HOOFDSTUK I De stad als religieuze ruimte 29 1. De stad als intellectueel en godsdienstig concept 30 2. De stad als religieuze ruimte in de paneelschilderkunst 37 2.1. Het aardse Jeruzalem 38 2.2. De stad als religieus theater 43 2.3. Het Hemelse Jeruzalem 47 3. Devotionele kunst, aardse intenties? 52 HOOFDSTUK II De adem van de stad: economische dimensie 55 1. De levensadem van de stad op paneel 57 1.1. De buik van de stad: het straatzicht 60 1.1.1. Een dalend gezichtspunt: van inkijk tot profiel 60 1.1.2. Het binnenzicht doorheen de vijftiende eeuw 62 1.2. De stad als economisch hart 75 1.3. Van kloppend hart tot de adem die stokt: op zoek naar een verklaring 84 5 1.3.1. Burgerlijke levensnabijheid of hoofse verfijning? 85 1.3.2. -

The Sparkling Stones in the Ghent Altarpiece and the Fountain of Life of Jan Van Eyck, Reflecting Cusanus and Jan Van Ruusbroec

Studies in Spirituality 24, 155-177. doi: 10.2143/SIS.24.0.3053495 © 2014 by Studies in Spirituality. All rights reserved. WOLFGANG CHRISTIAN SCHNEIDER THE SPARKLING STONES IN THE GHENT ALTARPIECE AND THE FOUNTAIN OF LIFE OF JAN VAN EYCK, REFLECTING CUSANUS AND JAN VAN RUUSBROEC For Lothar Graf zu Dohna, on the occasion of his ninetieth birthday, May 4th, 2014 SUMMARY – The rich use of precious stones in the panels of the Ghent Altarpiece is due to the presence of stones in the Rivers of Para- dise (Gn 2:10-14: onyx and bedolah, i.e. sardonyx or carnelian and jet) and in the goshen of the High Priest in Exodus (28.15 to 21), which inspired the description of the heavenly Jerusalem in the Apocalypse (21.9 to 21). Whereas within the Fountain of Life in the Prado, which since new investigations is to be ascribed to Jan van Eyck, on the side of the Synagogue all stones are concentrated in the Goshen, on the side of the Ecclesia the precious stones are spread over the spiritual and secular leaders. This later moment is maintained in the Ghent Altarpiece, in which Jan van Eyck in addition to the biblical sources picks up state- ments of Jan van Ruusbroec. Citing the Apocalypse the Flemish mystic spoke of a sparkling stone, which is given to the one, who transcends all things, and in it he gains light and truth and life. Exactly that was painted by Jan van Eyck. Mysticism is widely seen as a matter of the word: the figurative seems to be at best an illustration of what is said about the mystical appearances. -

1 BARBARA G. LANE Address: 535 East 86Th Street, 14F New York, NY

1 BARBARA G. LANE Address: 535 East 86th Street, 14F New York, NY 10028 Telephone: 212-988-6587 Fax: 212-988-5772 e-mail: [email protected] Education: B.A., Barnard College, 1963 Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, 1970 Employment: Curatorial Assistant, Department of Prints and Drawings, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1964-65 Instructor, University of Maryland, 1968-69 Lecturer, University of Pennsylvania, Summer, 1970 Assistant Professor, Camden College of Arts and Sciences, Rutgers University, 1970-76 Associate Professor, Douglass College, Rutgers University, 1976-79 (tenured) Associate Professor, Queens College, CUNY, 1979-84 (early tenure, 1983) Professor, Queens College, CUNY, 1985-present (on leave 1993-1995 and Spring, 1996); Chair, Art Department, 1985-1993, 1997-2000, 2003-2006, and 2008-2012 Research Scholar in Art History, Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, UCLA, 1993-1996 Professor, The Graduate Center, CUNY, 2000-present Fellowships and Awards: Kress Foundation Fellowship for Tuition and Fees, 1966-67 (University of Pennsylvania) University of Pennsylvania Dissertation Year Fellowship,1969-70 Rutgers University Research Council Summer Faculty Fellowship, 1972 Rutgers University Faculty Academic Study Program, Fall, 1974 and Spring, 1979 Rutgers University Research Council Grants, 1977-78 and Spring, 1979 Mellon Foundation Appointment as Associate Professor, Queens College, 1979 Faculty in Residence Award, Queens College, 1984-85 CUNY Fellowship Awards, Spring, 1986 and Spring, 1987 2 PSC-CUNY Research Awards, 1986-1987 and 1989-1990 National Endowment for the Humanities Travel to Collections Grant, 1987-1988 National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship for College Teachers, 1988-1989 CUNY Scholar Incentive Award, Feb. 1, 1989-Jan. -

The Value of Verisimilitude in the Art of Jan Van Eyck

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2929092 . Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Yale University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Yale French Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 146.201.208.22 on Wed, 17 Sep 2014 14:51:03 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions LINDA SEIDEL The Value of Verisimilitude in the Art of Janvan Eyck Verisimilitude, the appearanceof truth, was the quality most praised by Bartolommeo Fazio in his midfifteenth-century discussion of Jan van Eyck's painting. In a description of a triptych by Jan,the Genoese humanist noted an Angel Gabriel "with hair surpassingreality," and a donor lacking "only a voice;" Jerome, probablypainted on one of the wings, looked "like a living being in a library,"and the viewer had the impression when standing a bit away from the panel that the room "recedes inwards and that it has complete books laid open in it. ..." Fazio remarked that a viewer could measure the distance between places on a circular map of the world that Janpainted for the Duke of Burgundy;on another painting, the viewer could see both a nude wom- an's back as well as her face and breast through the judicious placement of a mirror.Indeed, Fazio noted, "almost nothing is more wonderful in this work than the mirror painted in the picture, in which you see whatever is represented as in a real mirror."' Although none of the paintings Fazio described has survived, no one doubts or discounts the substance of his praise. -

The Descent from the Cross in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum: a Small Manifesto of Brussels School Painting

The Descent from the Cross in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum: a small manifesto of Brussels School Painting Elodie De Zutter This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Archivo fotográfico de la Capilla Real de Granada: fig. 7 © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa-Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 1-2, 12-13, 15-16 and 18 © bpk / Gemäldegalerie, SMB / Jörg P. Anders: fig. 5 (right) © bpk / Staatsgalerie Stuttgart: figs. 8 and 19 Elisabeth Dhanens. Hugo Van der Goes. Antwerpen: Mercatorfond. Courtesy of Elodie De Zutter: fig. 5 (left) © Gallerie degli Uffizi. Gabinetto Fotografico: fig. 6 (left) © KIK-IRPA, Brussels: fig. 6 (right) Lefebvre & Gillet. Editions d’Art, 1985, fig. 124b: fig. 14 Musea Brugge © www.lukasweb.be - Art in Flanders vzw, photo Hugo Maertens: fig. 4 © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre): Michel Urtado: fig. 11 (left) / Tony Querrec: (right) Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016: fig. 3 Su concessione della Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e della Identità siciliana – Dipartimento dei Beni Culturali e della Identità siciliana – Museo interdisciplinare regionale di Messina: fig. -

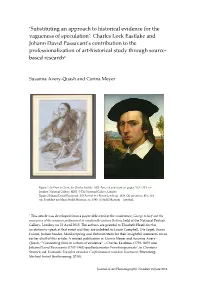

Charles Lock Eastlake and Johann David Passavant’S Contribution to the Professionalization of Art-Historical Study Through Source- Based Research1

‘Substituting an approach to historical evidence for the vagueness of speculation’: Charles Lock Eastlake and Johann David Passavant’s contribution to the professionalization of art-historical study through source- based research1 Susanna Avery-Quash and Corina Meyer Figure 1 Sir Francis Grant, Sir Charles Eastlake, 1853. Pen, ink and wash on paper, 29.3 x 20.3 cm. London: National Gallery, H202. © The National Gallery, London Figure 2 Johann David Passavant, Self-Portrait in a Roman Landscape, 1818. Oil on canvas, 45 x 31.6 cm. Frankfurt am Main: Städel Museum, no. 1585. © Städel Museum – Artothek 1 This article was developed from a paper delivered at the conference, George Scharf and the emergence of the museum professional in nineteenth-century Britain, held at the National Portrait Gallery, London, on 21 April 2015. The authors are grateful to Elizabeth Heath for the invitation to speak at that event and they are indebted to Lorne Campbell, Ute Engel, Susan Foister, Jochen Sander, Marika Spring and Deborah Stein for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article. A related publication is: Corina Meyer and Susanna Avery- Quash, ‘“Connecting links in a chain of evidence” – Charles Eastlakes (1793-1865) und Johann David Passavants (1787-1861) quellenbasierter Forschungsansatz’, in Christina Strunck, ed, Kulturelle Transfers zwischen Großbritannien und dem Kontinent, Petersberg: Michael Imhof (forthcoming, 2018). Journal of Art Historiography Number 18 June 2018 Avery-Quash and Meyer ‘Substituting an approach to historical evidence for the vagueness of speculation’ ... Introduction After Sir Charles Eastlake (1793-1865; Fig. 1) was appointed first director of the National Gallery in 1855, he spent the next decade radically transforming the institution from being a treasure house of acknowledged masterpieces into a survey collection which could tell the story of the development of western European painting.