Ecophenotypic Variations of Encrinus Liliiformis (Echinodermata: Crinoidea) from the Middle Triassic Muschelkalk of Southwest Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Persistent and Widespread Occurrence of Bioactive Quinone Pigments During Post-Paleozoic Crinoid Diversification

Persistent and widespread occurrence of bioactive quinone pigments during post-Paleozoic crinoid diversification Klaus Wolkenstein1 Department of Geobiology, Geoscience Centre, University of Göttingen, 37077 Göttingen, Germany Edited by Tomasz K. Baumiller, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, and accepted by the Editorial Board January 20, 2015 (received for review September 9, 2014) Secondary metabolites often play an important role in the adapta- (14, 15), closely related to the gymnochromes, suggesting that the tion of organisms to their environment. However, little is known fossil pigments may be only slightly changed during diagenesis. about the secondary metabolites of ancient organisms and their Although violet coloration has been occasionally observed in fossil evolutionary history. Chemical analysis of exceptionally well-pre- crinoids (e.g., refs. 16 and 17), until now, only very few chemical served colored fossil crinoids and modern crinoids from the deep sea proofs of quinone pigments have been found for crinoids other than suggests that bioactive polycyclic quinones related to hypericin Liliocrinus (14, 15, 18, 19). Recent measurements suggested the were, and still are, globally widespread in post-Paleozoic crinoids. presence of quinone-like compounds in Paleozoic (Mississippian) The discovery of hypericinoid pigments both in fossil and in present- crinoids (20), but the identity of these compounds has been ques- day representatives of the order Isocrinida indicates that the pig- tioned on methodological grounds (21). ments remained almost unchanged since the Mesozoic, also suggest- To investigate the general occurrence of polycyclic quinone ing that the original color of hypericinoid-containing ancient crinoids pigments in the Crinoidea, the coloration of numerous fossil may have been analogous to that of their modern relatives. -

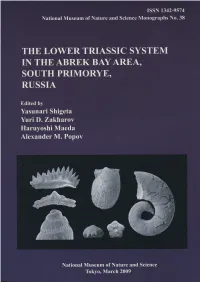

Monograph38.Pdf

The Lower Triassic System in the Abrek Bay area, South Primorye, Russia Edited by Yasunari Shigeta Yuri D. Zakharov Haruyoshi Maeda Alexander M. Popov National Museum of Nature and Science Tokyo, March 2009 v Contents Contributors .................................................................vi Abstract ....................................................................vii Introduction (Y. Shigeta, Y. D. Zakharov, H. Maeda, A. M. Popov, K. Yokoyama and H. Igo) ...1 Paleogeographical and geological setting (Y. Shigeta, H. Maeda, K. Yokoyama and Y. D. Zakharov) ....................3 Stratigraphy (H. Maeda, Y. Shigeta, Y. Tsujino and T. Kumagae) .........................4 Biostratigraphy Ammonoid succession (Y. Shigeta, H. Maeda and Y. D. Zakharov) ..................24 Conodont succession (H. Igo) ...............................................27 Correlation (Y. Shigeta and H. Igo) ...........................................29 Age distribution of detrital monazites in the sandstone (K. Yokoyama, Y. Shigeta and Y. Tsutsumi) ..............................30 Discussion Age data of monazites (K. Yokoyama, Y. Shigeta and Y. Tsutsumi) ..................34 The position of the Abrek Bay section in the “Ussuri Basin” (Y. Shigeta and H. Maeda) ...36 Ammonoid mode of occurrence (H. Maeda and Y. Shigeta) ........................36 Aspects of ammonoid faunas (Y. Shigeta) ......................................38 Holocrinus species from the early Smithian (T. Oji) ..............................39 Recovery of nautiloids in the Early Triassic (Y. Shigeta) -

Encrinus Liliiformis (Echinodermata: Crinoidea)

RESEARCH ARTICLE Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis of the Fossil Crinoid Encrinus liliiformis (Echinodermata: Crinoidea) Janina F. Dynowski1,2, James H. Nebelsick2*, Adrian Klein3, Anita Roth-Nebelsick1 1 Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany, 2 Fachbereich Geowissenschaften, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, 3 Institut für Zoologie, Rheinische Friedrich- Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Bonn, Germany * [email protected] a11111 Abstract Crinoids, members of the phylum Echinodermata, are passive suspension feeders and catch plankton without producing an active feeding current. Today, the stalked forms are known only from deep water habitats, where flow conditions are rather constant and feeding OPEN ACCESS velocities relatively low. For feeding, they form a characteristic parabolic filtration fan with their arms recurved backwards into the current. The fossil record, in contrast, provides a Citation: Dynowski JF, Nebelsick JH, Klein A, Roth- Nebelsick A (2016) Computational Fluid Dynamics large number of stalked crinoids that lived in shallow water settings, with more rapidly Analysis of the Fossil Crinoid Encrinus liliiformis changing flow velocities and directions compared to the deep sea habitat of extant crinoids. (Echinodermata: Crinoidea). PLoS ONE 11(5): In addition, some of the fossil representatives were possibly not as flexible as today’s cri- e0156408. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156408 noids and for those forms alternative feeding positions were assumed. One of these fossil Editor: Stuart Humphries, University of Lincoln, crinoids is Encrinus liliiformis, which lived during the middle Triassic Muschelkalk in Central UNITED KINGDOM Europe. The presented project investigates different feeding postures using Computational Received: August 24, 2015 Fluid Dynamics to analyze flow patterns forming around the crown of E. -

The Permian-Triassic Transition in Southern Armenia

IGCP 630: Permian and Triassic integrated Stratigraphy and Climatic, Environmental and Biotic Extremes THE PERMIAN-TRIASSIC TRANSITION IN SOUTHERN ARMENIA October 8th - 14th, 2017 5 th IGCP 630 International conference and field workshop, 8-14 October, 2017 Yerevan, Armenia Workshop schedule: October 8: Arrival in Yerevan, transfer to a hotel. October 9: Conference Day 1, at the Round Hall of Presidium of the Armenian National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan. October 10: Conference Day 2, at the Round Hall of Presidium of the Armenian National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan., and Visit of the Khor Virap monastery and the Matenadaran Scientific Research Institute of Ancient Manuscripts. October 11: Field Trip, Day 1, Yerevan to Ogbin (166 km by bus). Visit to the Ogbin outcrop section. Accommodation in the Hotel Amrots in the city of Vayk. October 12: Field Trip, Day 2, Vayk to Zangakatun, 50km. Visit to the Chanakhchi outcrop section. Return to Hotel Amrots. October 13: Field Trip, Day 3, Vayk to Vedi (86km). Visit to the Vedi outcrop sections and visit of the Noravank monastery. Return to Yerevan (67 km), Conference dinner in evening. October 14: Samples packing for expedition, departure of the participants in the afternoon or in the night. 2 5 th IGCP 630 International conference and field workshop, 8-14 October, 2017 Yerevan, Armenia CONTENTS Workshop schedule ......................................................................................................................... 2 Conference Programm .................................................................................................................... -

Onetouch 4.0 Sanned Documents

• 1- \ BuJletin of Zoological Nomenciature 54(1) March 1997 Case 2999 Umbellula Cuvier, [17971 (Cnidaria, Anthozoa): proposed conservation as the correct original spelling, and corrections to the entries relating to Umbelluiaria Lamarck. 1801 on the Official Lists and Indexes of Names in Zoology Frederick M. Bayer Depariment of ¡nvertebraie Zoology, National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. 20560. U.S.A. Manfred Grasshoff Forschungsinstitut und Museum Senckenberg, Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main. Germany Abstract. Cuvier [1797] published the generic name Omhelluia for a species of Arctic deep-sea pennatuiacean (sea pen) which had been named Isis encrinus by Linnaeus (1758). In 1800 Cuvier spelled the name as Umbellula, and this generic name for U. encrinus and other species has been widely and universally used for more than 120 years. A recent work has used the spelling Ombelluta for the first time since 1797, and the conservation of Umbellula is proposed. Umbelluiaria Lamarck. 1801, a junior objective synonym of Umbellula, was in usage dunng the eadier part of the 19th-century: the entries on the Official Lists and Indexes of Generic and Family-Group Names relating to this name are erroneous and corrections are proposed. Keywords. Nomenclature; taxonomy: Anthozoa; Pennatuiacea; sea pens; Ombellula: Umbellula; Umbelluiaria; Umbellula encrinus. 1. John Ellis (1753, ¡755) described and illustrated one of two specimens of a giant deep-sea pennatuiacean collected at latitude 79'N. near Greenland (perhaps really Spitzbergen: Lindahl. 1874, pp. 3, 14) by Captain Adrians of the whaling ship Britannia (for the history of these and other specimens see Gray, 1870, Lindahl, 1874 and Danielssen & Keren, 1884), Ellis named the species as 'Hydra marina árctica' or 'Clustered Sea-Polype'. -

University of Nevada Reno Paleoecology of Upper Triassic

University of Nevada Reno Paleoecology of Upper Triassic Bioherms in the Pilot Mountains, Mineral County, West-Central Nevada A tiles is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology by Diane Elinor Cornwall May 1979 University of Nevada Reno ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. James R. Firby for his supervision, support and for his guidance through those difficult "rough spots." Dan Howe was a constant source of interesting ideas and enthusiasm, especially during the early stages of the thesis project. Throughout my research Fred Gustafson and I worked together, he always being an interested and understanding coworker and friend throughout the lonely weeks of research. Dr. Joseph Lintz, Jr. was invaluable in his assistance in procurement of materials and equipment and in his unselfish desire to solve any problem. I thank Dr. Mead for joining my committee. I greatly appreciate those hearty souls who ventured out into the desert with me and braved the hazards and extremes; these include Barbara Foster, Mickie Dunn, Micheal Judge and my parents who spent all their vacations in my field area. I would also like to acknowledge the moral support given by my parents, special and other friends. i n ABSTRAC In the Pilot Mountains, Mineral County, Nevada, up to five horizons of bioherms are present within the top 76 meters of the lower member of the Upper Triassic (Karnian) Luning Formation. These bio herms are located in the carbonate portions of small terrigenous- carbonate rhythms. The biohermal mounds, less than 15 meters high^exhibit four of Wilson's (1975) seven facies. -

Benthic Crinoids from the Triassic Cassian Formation of the Dolomites

Geo.Alp, Vol. 8, S. 128–135, 2011 BENTHIC CRINOIDS FROM THE TRIASSIC CASSIAN FORMATION OF THE DOLOMITES Hans Hagdorn With 2 Plates Muschelkalkmuseum, Schlossstraße 11, 74653 Ingelfingen, Germany Email: [email protected] The marls of the late Ladinian/early Carnian Cassian Formation have been painstakingly searched for more than 170 years for the beautifully preserved fossils that make this Fossillagerstätte one of the richest treasure troves of Meso- zoic invertebrates. Its crinoid fauna is the most diverse Triassic fauna known from the western Tethys. However, unlike the obrutional conservation lagerstätten in the late Anisian/early Ladinian germanotype Muschelkalk, which has much less diverse crinoid faunas, articulated skeletons are extremely rare in the Cassian Formation. This is due to a relatively long transport from their original habitat to the area of deposition. Hence, the variety of crinoid sclerites forms a puzzle with many parts is still missing. Most of the taxa established during the last 170 years are based on fragmentary material, mostly columnals, many of which are of limited diagnostic value and cannot be unequivocally attributed to a genus or even a species. For Count Münster (1834) cylindrical columnals similar to Encrinus liliiformis gave evidence for a Muschelkalk (Triassic) age of the Cassian Formation. Subsequently the Cassian crinoids were described within the classical monographs (Münster, 1841; Klipstein, 1845; Laube, 1864, 1865). New taxa were added by Bather (1909), Leonardi & Lovo (1950) and Zardini (1974), most of them as a result of Rinaldo Zardini´s collecting activity around Cortina d´ Ampezzo. Hagdorn (1988, 2004) started to subdivide the order Encrinida. -

Forum Reply Doi:10.1130/G39221Y.1

Forum Reply doi:10.1130/G39221Y.1 Paleozoic echinoderm hangovers: Waking up in the Triassic Ben Thuy in the ossicles shown on our figures 1B and 1C as evidence for their 1Natural History Museum Luxembourg, Department of Palaeontology, claim. This statement left us somewhat puzzled, as rounded edges are a Luxembourg 2160, Luxembourg typical feature of test plates in many Paleozoic echinoids including the 2Muschelkalkmuseum Ingelfingen, 74653 Ingelfingen, Germany 3 proterocidaroids (e.g., McCoy, 1849). This is even visible to the non- School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Portsmouth, specialist eye when taking a closer look at the plate shapes in the Portsmouth PO1 3QL, UK articulated echinoid specimen shown on our figure DR3. Furthermore, Salamon and Gorzelak raised the possibility of conver- We thank Salamon and Gorzelak for their Comment (Salamon and gent evolution to explain the similarities between Upper Paleozoic and Gorzelak, 2017) on our recent Geology paper (Thuy et al., 2017) on the Triassic echinoderms. Unless the authors intend to challenge the very discovery of Paleozoic echinoderms surviving into the Triassic, fundament of phylogeny, they will acknowledge that stratigraphic range corroborating the provocative nature of the topic. Salamon and Gorzelak extension of Paleozoic lineages is by far the most parsimonious argue that we failed to address the issue of a possible reworking of explanation for the presence of multiserial test plating in a Triassic Paleozoic echinoderm fossils into Triassic sediments. We agree that echinoid and ambulacral grove spines in a Triassic ophiuroid, only to echinoderm fossils can be sturdy enough to survive re-sedimentation highlight the most striking examples. -

Hagdorn 1999 Triassic Muschelkalk of Central Europe

21 Triassic Muschelkalk of Central Europe HANS HAGDORN WITCHES’ MONEY AND CHICKEN LEGS: stones, a translation of their trivial German name, Ra¨d- THE RESEARCH HISTORY OF ersteine) for single columnals and ‘ Entrochus’ for pluri- ENCRINUS LILIIFORMIS columnals. A hundred years later, Fridericus Lachmund, in Oryctographia Hildesheimensis (1669), illustrated col- Long before the advent of scientific palaeontology, com- umnals, cups and cup elements (Pentagonus) as well as a mon fossils were connected with superstition and leg- fragmentary crown, the arms of which he compared to ends of popular belief (Abel 1939). In Lower Saxony chicken legs. Misinterpreting Agricola, he transferred the abundant columnals of the Muschelkalk sea lily En- the name ‘Encrinus’ to these fossils. From that time crinus liliiformis were called Sonnenra¨der (sun wheels), onward, the name ‘Encrinus’ became attached to this and in Thuringia and Hessia they were called Bonifa- common and earliest recognized crinoid crown. In 1719 tiuspfennige (St. Boniface’s pennies) because the saint the Hamburg physician Michael Reinhold Rosinus fig- who baptised the German tribes was said to have cursed ured complete crowns and elements of crown and stem all the pagan money, which turned into stone. In south- that he regarded as fragments of some kind of starfish. western Germany, Encrinus columnals were called Hex- Other 18th-century authors explained them as vertebrae engeld (witches’ money). According to a legend from of sea animals, marine plants, corals or parts of ‘Jew Beuthen in Upper Silesia, in 1276 St. Hyacinth’s rosary stones’ (sea urchins). Finally, the complete animal was broke when he was praying at a fountain, and the beads correctly reconstructed by Johann Christophorus Har- dropped into the water. -

Hydrodynamic Analysis of Suspension Feeding in Recent and Fossil Crinoids

Hydrodynamic analysis of suspension feeding in recent and fossil crinoids Dissertation der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) vorgelegt von Dipl. Geol. Janina Friederike Dynowski aus Siegen Tübingen 2014 Tag der mündlichen Qualifikation: 24.02.2015 Dekan: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Rosenstiel 1. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. James H. Nebelsick 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Oliver Betz Danksagung Mein besonderer Dank gilt meinen Betreuern Prof. Dr. James H. Nebelsick und PD Dr. Anita Roth-Nebelsick für die Vergabe und gemeinsame Entwicklung dieses spannenden Themas, und die sehr gute Betreuung während der Doktorarbeit, im Zuge derer mir sehr viel Raum und Freiheit für die Realisierung des Projektes gelassen wurde. Mein Dank gilt außerdem Prof. Dr. Oliver Betz für die Begutachtung der Dissertation und PD Dr. Dr. Wilfried Konrad für anregende Diskussionen und viele konstruktive Hinweise. Weiterhin möchte ich Prof. Dr. Horst Bleckmann und Dr. Adrian Klein für die Kooperation und tatkräftige Unterstützung während und nach der Durchführung der PIV-Messungen im Strö- mungskanal des Instituts für Zoologie der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn danken. Besonderer Dank gilt auch Christiane Schott und Matthias Boller für die Hilfe beim Bau der Strömungskanalmodelle, sowie allen weiteren Kollegen am Staatlichen Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart und der Arbeitsgruppe Invertebratenpaläontologie und Paläoklimato- logie der Universität Tübingen. Mein Dank gilt außerdem dem Team des ZDV Tübingen für die Unterstützung bei der Nut- zung der HPC-Ressourcen der bwGRiD-Initiative und des bwUniClusters, der DFG und dem DAAD für die finanzielle Förderung dieses Forschungsprojektes, sowie der Paläontolo- gischen Gesellschaft für die Würdigung meiner Arbeit durch die Auszeichnung mit dem „Zukunfspreis für junge Paläontologen/innen“ auf der Jahrestagung 2011 in Wien. -

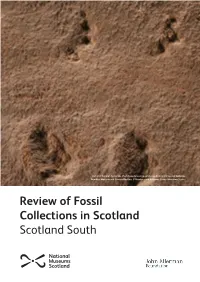

Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Scotland South Scotland South

Detail of Permian footprints Chelichnus duncani in sandstone from Dumfries and Galloway. Dumfries Museum and Camera Obscura. © Dumfries and Galloway Council Museums Service Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Scotland South Scotland South Dumfries Museum and Camera Obscura (Dumfries and Galloway Council) Sanquhar Tolbooth Museum (Dumfries and Galloway Council) Stranraer Museum (Dumfries and Galloway Council) Gem Rock Museum Newton Stewart Museum Tweeddale Museum (Live Borders) Hawick Museum (Live Borders) 1 Dumfries Museum and Camera Obscura (Dumfries and Galloway Council) Collection type: Local authority Accreditation: 2018 The Observatory, Rotchell Road, Dumfries, DG2 7SW Contact: [email protected] Location of collections The original Museum was located in a windmill dating from the late 1700s, preserved in the 1830s by the newly-formed Dumfries and Maxwelltown Astronomical Society for use as an observatory. An extension built in the 1860s added a large gallery and mezzanine level with further gallery and storage space added in the 1980s. Collections are onsite in displays and a main storeroom. Size of collections 1,000-1,200 fossils. Onsite records Information is in an Adlib CMS database transcribed from several previous electronic systems and various paper documents, such as MDA and other index card systems, Gift Books, Accession Registers, free text catalogues, inventories and listings. Fossils are catalogued with other geological material as a series of numbered boxes with a list compiled in the 1980s by James Williams (1944- 2009). An online catalogue is available at: https://dgc-web.adlibhosting.com/home but does not yet contain fossil entries. Collection highlights 1. Permian vertebrate trackways from Locharbriggs and Corncockle quarries linked to Reverend Henry Duncan (1774-1846) and former curator Alfred Truckell (1919-2007). -

Encrinus Aculeatus Von Meyer, 1849 (Crinoidea, Encrinidae

Published on “Swiss Journal of Palaeontology”, The final publication is available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13358-018-0170-0 Received: 27 June 2018 / Accepted: 12 October 2018, published online: 1 November 2018 Encrinus aculeatus von Meyer, 1849 (Crinoidea, Encrinidae) from the Middle Triassic of Val Brembana (Alpi Orobie, Bergamo, Italy) 1 2 3 Hans Hagdorn • Fabrizio Berra • Andrea Tintori Corrseponding Author: Hans Hagdorn ([email protected]) 1) Muschelkalkmuseum Ingelfingen, Schloss-Straße 11, 74653 Ingelfingen, Germany 2) Dipartimento di Scienze, della Terra ‘A. Desio’, Via Mangiagalli 34, 20133 Milano, Italy 3) Triassica-Institute for Triassic Lagerstaetten, Perledo, LC, Italy Editorial Handling: C. Klug. Abstract The Triassic crinoid Encrinus aculeatus is described from a single bedding plane of uncertain Pelsonian or early Illyrian or (less probable) late Ladinian origin from Val Brembana (Alpi Orobie, Bergamo, Italy) based on 36 more or less complete crowns and columns. The specimens represent an obrutional echinoderm lagersta¨tte of the Muschelkalk type. The individuals are semi-adult and juvenile; adult individuals are lacking. Morphological description and comparison with the holotype and additional material from the Lower Muschelkalk and basal Middle Muschelkalk of Upper Silesia (Poland) prove the assignment to Encrinus aculeatus. However, the species concept of genus Encrinus is critical because several characters are inconsistent. E. aculeatus occurs in the Middle Triassic (Bithynian to early Illyrian, ? early Ladinian) of the western Tethys shelf and Peritethys basins (Southern Alps, Balaton Upland, Germanic Basin). Encrinus aculeatus is regarded ancestral to the Upper Muschelkalk (latest Illyrian) E. liliiformis. Until now, E. liliiformis has not yet been proven with certainty from outside the Germanic Basin; references are based on isolated and undiagnostic material.