Morphological Studies on the Echinoderms: a Translation of Études Morphologiques Sur Les Échinodermes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Customer-Product

AQUATIC DESIGN CENTRE 26 Zennor Trade Park Balham ¦ London ¦ SW12 0PS Shop Enquiries Tel: 020 7580 6764 Email: [email protected] PLEASE CALL TO CHECK AVAILABILITY ON DAY In Stock Yes/No Marine Invertebrates and Corals Anemones Common name Scientific name Atlantic Anemone Condylactis gigantea Atlantic Anemone - Pink Condylactis gigantea Beadlet Anemone - Red Actinea equina Y Bubble Anemone - Coloured Entacmaea quadricolor Y Bubble Anemone - Common Entacmaea quadricolor Bubble Anemone - Red Entacmaea quadricolor Caribbean Anemone Condylactis spp. Y Carpet Anemone - Coloured Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Common Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard Blue Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard Common Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard Green Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard Red Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard White Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Mini Maxi Stichodactyla tapetum Carpet Anemone - Soft Blue Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Common Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Green Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Purple Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Red Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft White Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Yellow Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Striped Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - White Stichodactyla haddoni Curly Q Anemone Bartholomea annulata Flower Anemone - White/Green/Red Epicystis crucifer Malu Anemone - Common Heteractis crispa Malu Anemone - Pink Heteractis -

(Echinoidea, Echinidae) (Belgium) by Joris Geys

Meded. Werkgr. Tert. Kwart. Geol. 26(1) 3-10 1 fig., 1 tab., 1 pi. Leiden, maart 1989 On the presence of Gracilechinus (Echinoidea, Echinidae) in the Late Miocene of the Antwerp area (Belgium) by Joris Geys University of Antwerp (RUCA), Antwerp, Belgium and Robert Marquet Antwerp, Belgium. Geys, J., & R. Marquet. On the presence of Gracilechinus (Echinoidea, in the of — Echinidae) Late Miocene the Antwerp area (Belgium). Meded. Werkgr. Tert. Kwart. Geol., 26(1): 00-00, 1 fig., 1 tab., 1 pi. Leiden, March 1989. Some well-preserved specimens of the regular echinoid Gracilechinus gracilis nysti (Cotteau, 1880) were collected in a temporary outcrop at Borgerhout-Antwerp, in sandstones reworked from the Deurne Sands (Late Miocene). The systematic status of this subspecies is discussed. The present state of knowledge of the Echinidae from the Neogene of the North Sea Basin is reviewed. Prof. Dr J. Geys, Dept. of Geology, University of Antwerp (RUCA), Groenenborgerlaan 171, B-2020 Antwerp, Belgium. Dr R. Marquet, Constitutiestraat 50, B-2008 Antwerp, Belgium, Contents — 3 Introduction, p. 4 Systematic palaeontology, p. 6 Discussion, p. Echinidae in the Neogene of the North Sea Basin—some considerations on 8 systematics, p. 10. References, p. INTRODUCTION extensive excavations the of E17-E18 indicated E3 Because of along western verge motorway (also as ‘Kleine and Ring’) at Borgerhout-Antwerp (Belgium), a remarkable outcrop of Neogene Quaternary beds accessible from The was March to November 1987. outcrop was situated between this motorway and the and extended from the the both ‘Singel’-road, ‘Stenenbrug’ to ‘Zurenborgbrug’, on sides 4 of the exit. -

Persistent and Widespread Occurrence of Bioactive Quinone Pigments During Post-Paleozoic Crinoid Diversification

Persistent and widespread occurrence of bioactive quinone pigments during post-Paleozoic crinoid diversification Klaus Wolkenstein1 Department of Geobiology, Geoscience Centre, University of Göttingen, 37077 Göttingen, Germany Edited by Tomasz K. Baumiller, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, and accepted by the Editorial Board January 20, 2015 (received for review September 9, 2014) Secondary metabolites often play an important role in the adapta- (14, 15), closely related to the gymnochromes, suggesting that the tion of organisms to their environment. However, little is known fossil pigments may be only slightly changed during diagenesis. about the secondary metabolites of ancient organisms and their Although violet coloration has been occasionally observed in fossil evolutionary history. Chemical analysis of exceptionally well-pre- crinoids (e.g., refs. 16 and 17), until now, only very few chemical served colored fossil crinoids and modern crinoids from the deep sea proofs of quinone pigments have been found for crinoids other than suggests that bioactive polycyclic quinones related to hypericin Liliocrinus (14, 15, 18, 19). Recent measurements suggested the were, and still are, globally widespread in post-Paleozoic crinoids. presence of quinone-like compounds in Paleozoic (Mississippian) The discovery of hypericinoid pigments both in fossil and in present- crinoids (20), but the identity of these compounds has been ques- day representatives of the order Isocrinida indicates that the pig- tioned on methodological grounds (21). ments remained almost unchanged since the Mesozoic, also suggest- To investigate the general occurrence of polycyclic quinone ing that the original color of hypericinoid-containing ancient crinoids pigments in the Crinoidea, the coloration of numerous fossil may have been analogous to that of their modern relatives. -

SI Appendix for Hopkins, Melanie J, and Smith, Andrew B

Hopkins and Smith, SI Appendix SI Appendix for Hopkins, Melanie J, and Smith, Andrew B. Dynamic evolutionary change in post-Paleozoic echinoids and the importance of scale when interpreting changes in rates of evolution. Corrections to character matrix Before running any analyses, we corrected a few errors in the published character matrix of Kroh and Smith (1). Specifically, we removed the three duplicate records of Oligopygus, Haimea, and Conoclypus, and removed characters C51 and C59, which had been excluded from the phylogenetic analysis but mistakenly remain in the matrix that was published in Appendix 2 of (1). We also excluded Anisocidaris, Paurocidaris, Pseudocidaris, Glyphopneustes, Enichaster, and Tiarechinus from the character matrix because these taxa were excluded from the strict consensus tree (1). This left 164 taxa and 303 characters for calculations of rates of evolution and for the principal coordinates analysis. Other tree scaling methods The most basic method for scaling a tree using first appearances of taxa is to make each internal node the age of its oldest descendent ("stand") (2), but this often results in many zero-length branches which are both theoretically questionable and in some cases methodologically problematic (3). Several methods exist for modifying zero-length branches. In the case of the results shown in Figure 1, we assigned a positive length to each zero-length branch by having it share time equally with a preceding, non-zero-length branch (“equal”) (4). However, we compared the results from this method of scaling to several other methods. First, we compared this with rates estimated from trees scaled such that zero-length branches share time proportionally to the amount of character change along the branches (“prop”) (5), a variation which gave almost identical results as the method used for the “equal” method (Fig. -

PUNIC ECHINODERM REMAINS Excavated from Tas-Silg, Malta

PUNIC ECHINODERM REMAINS Excavated from Tas-Silg, Malta C. Savona-Ventura Report submitted to the Department of Archaeology, University of Malta, 1999 The Tas-Silg Punic site is situated at an elevation of about 125 feet above sea level. This situation, together with the significant distance from the shore (circa 700 metres), makes it highly unlikely that marine animal remains excavated from the site represent shore wash. There are more likely to have been brought to the site by man. There is evidence to believe that since prehistoric and possibly classical times, the southeastern coast of Malta has gradually tilted towards the sea. The evidence for sinking during the classical period may be inferred by the presence of cart-ruts which cease suddenly at the edge of the water at Birzebbugia (St. George’s Bay) and cart- ruts which together with artificial caldrons occur beneath the water at Marsaxlokk. 1 This means that the Tas-Silg site was probably even higher above sea-level during the classical period than at present. Echinoderm remains were excavated in plentiful amounts from the site. The amount of fragments obtained from the site further suggests that these represent intentional transportation to the site by the action of man. Accidental transportation is unlikely to have accounted for large quantities of this marine animal. Two small fragments were obtained from the Tas-Silg Punic site on 22nd July 1998. The fragments represent 3 fused and one separate inter-ambulacral plates. The spine pattern of each inter-ambulacral plate is diagrammatically represented below. The spine pattern was characterised by large spines surrounded by a satellite series of smaller spines. -

Spatangus Purpureus O.F. Müller, 1776

Spatangus purpureus O.F. Müller, 1776 AphiaID: 124418 VIOLET HEART-URCHIN Animalia (Reino) > Echinodermata (Filo) > Echinozoa (Subfilo) > Echinoidea (Classe) > Euechinoidea (Subclasse) > Irregularia (Infraclasse) > Atelostomata (Superordem) > Spatangoida (Ordem) > Brissidina (Subordem) > Spatangoidea (Superfamilia) > Spatangidae (Familia) © Vasco Ferreira Hans Hillewaert Roberto Pillon Facilmente confundível com: 1 Echinocardium cordatum Ouriço-coração Sinónimos Prospatangus purpureus (O.F. Müller, 1776) Spatagus purpureus O.F. Müller, 1776 Spatangus meridionalis Risso, 1825 Spatangus Regina Spatangus reginae Gray, 1851 Spatangus spinosissimus Desor in L. Agassiz & Desor, 1847b Referências additional source Hansson, H. (2004). North East Atlantic Taxa (NEAT): Nematoda. Internet pdf Ed. Aug 1998., available online at http://www.tmbl.gu.se/libdb/taxon/taxa.html [details] basis of record Hansson, H.G. (2001). Echinodermata, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels,. 50: pp. 336-351. [details] additional source Southward, E.C.; Campbell, A.C. (2006). [Echinoderms: keys and notes for the identification of British species]. Synopses of the British fauna (new series), 56. Field Studies Council: Shrewsbury, UK. ISBN 1-85153-269-2. 272 pp. [details] additional source Muller, Y. (2004). Faune et flore du littoral du Nord, du Pas-de-Calais et de la Belgique: inventaire. [Coastal fauna and flora of the Nord, Pas-de-Calais and Belgium: inventory]. Commission Régionale de Biologie Région Nord Pas-de-Calais: France. 307 pp., available online at http://www.vliz.be/imisdocs/publications/145561.pdf [details] original description Müller, O. F. (1776). Zoologiae Danicae prodromus: seu Animalium Daniae et Norvegiae indigenarum characteres, nomina, et synonyma imprimis popularium. -

Monograph38.Pdf

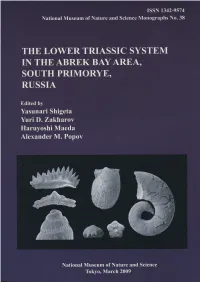

The Lower Triassic System in the Abrek Bay area, South Primorye, Russia Edited by Yasunari Shigeta Yuri D. Zakharov Haruyoshi Maeda Alexander M. Popov National Museum of Nature and Science Tokyo, March 2009 v Contents Contributors .................................................................vi Abstract ....................................................................vii Introduction (Y. Shigeta, Y. D. Zakharov, H. Maeda, A. M. Popov, K. Yokoyama and H. Igo) ...1 Paleogeographical and geological setting (Y. Shigeta, H. Maeda, K. Yokoyama and Y. D. Zakharov) ....................3 Stratigraphy (H. Maeda, Y. Shigeta, Y. Tsujino and T. Kumagae) .........................4 Biostratigraphy Ammonoid succession (Y. Shigeta, H. Maeda and Y. D. Zakharov) ..................24 Conodont succession (H. Igo) ...............................................27 Correlation (Y. Shigeta and H. Igo) ...........................................29 Age distribution of detrital monazites in the sandstone (K. Yokoyama, Y. Shigeta and Y. Tsutsumi) ..............................30 Discussion Age data of monazites (K. Yokoyama, Y. Shigeta and Y. Tsutsumi) ..................34 The position of the Abrek Bay section in the “Ussuri Basin” (Y. Shigeta and H. Maeda) ...36 Ammonoid mode of occurrence (H. Maeda and Y. Shigeta) ........................36 Aspects of ammonoid faunas (Y. Shigeta) ......................................38 Holocrinus species from the early Smithian (T. Oji) ..............................39 Recovery of nautiloids in the Early Triassic (Y. Shigeta) -

Helsingin Akvaariokeskus Lista Päivitetty 3.8.2018 Tilaus Tulee

Helsingin Akvaariokeskus lista päivitetty 3.8.2018 Tilaus tulee täältä parin viikon välein. Nouto elävillä ehdottomasti toimituspäivänä Pyydä hintatiedot spostitse [email protected] muista AINA mainita listan nimi (DeJong) sekä koodi, jonka hinnan haluat tietää * Saatavilla satunnaisesti ** Harvoin saatavilla *** Hyvin harvinaisia, saatavilla vain pyynnöstä MAC MAC Certified Species CUL Kasvatetut korallit ! Hyvin herkkiä kuljetukselle H Käsinpyydetyt ilman myrkkyä T.R. Viljellyt C Lajien mukana tulee cites paperit Asno Liike Number Latin name Stock 000022 H Acanthurus bahianus 4 000042 H Acanthurus bariene 1 000051 H Acanthurus chirurgus 10 000052 H Acanthurus chirurgus 10 000063 H* Acanthurus tristis 1 000072 H Acanthurus coeruleus 5 000073 H Acanthurus coeruleus 2 000082 H* Acanthurus dussumieri 1 000091 H Acanthurus nigricans 1 000092 H Acanthurus nigricans 3 000093 H Acanthurus nigricans 4 000111 H* Acanthurus guttatus 2 000122 H Acanthurus japonicus 10 000123 H Acanthurus japonicus 1 000152 H Acanthurus leucocheilus 2 000162 H Acanthurus lineatus 8 000163 H Acanthurus lineatus 1 000172 H Acanthurus mata 1 000173 H Acanthurus mata 1 000181 H* Acanthurus maculiceps 1 000223 H Acanthurus nigrofuscus 4 000241 H* Acanthurus leucosternon (hybrid) 1 000242 H* Acanthurus leucosternon (hybrid) 1 000251 H Acanthurus olivaceus 6 000271 H Acanthurus Chronixis 2 000291 H Acanthurus tennentii 1 000293 H Acanthurus tennentii 1 000304 H Acanthurus thompsoni 1 000312 H Acanthurus triostegus 18 000313 H Acanthurus triostegus 4 000331 -

Marlin Marine Information Network Information on the Species and Habitats Around the Coasts and Sea of the British Isles

MarLIN Marine Information Network Information on the species and habitats around the coasts and sea of the British Isles Edible sea urchin (Echinus esculentus) MarLIN – Marine Life Information Network Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Review Dr Harvey Tyler-Walters 2008-04-29 A report from: The Marine Life Information Network, Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Please note. This MarESA report is a dated version of the online review. Please refer to the website for the most up-to-date version [https://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/detail/1311]. All terms and the MarESA methodology are outlined on the website (https://www.marlin.ac.uk) This review can be cited as: Tyler-Walters, H., 2008. Echinus esculentus Edible sea urchin. In Tyler-Walters H. and Hiscock K. (eds) Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews, [on-line]. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.17031/marlinsp.1311.1 The information (TEXT ONLY) provided by the Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Note that images and other media featured on this page are each governed by their own terms and conditions and they may or may not be available for reuse. Permissions beyond the scope of this license are available here. Based on a work at www.marlin.ac.uk (page left blank) Date: 2008-04-29 Edible sea urchin (Echinus esculentus) - Marine Life Information Network See online review for distribution map Echinus esculentus and hermit crabs on grazed rock. -

Chemical Ecology of Echinoderms: Impact of Environment and Diet in Metabolomic Profile

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade do Minho: RepositoriUM Chapter CHEMICAL ECOLOGY OF ECHINODERMS: IMPACT OF ENVIRONMENT AND DIET IN METABOLOMIC PROFILE David M. Pereira1 ,2*, Paula B. Andrade3, Ricardo A. Pires1,2, Rui L. Reis1,2 1 3B’s Research Group - Biomaterials, Biodegradables and Biomimetics, University of Minho, Headquarters of the European Institute of Excellence on Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, Taipas, Guimarães, Portugal 2 ICVS/3B’s - PT Government Associate Laboratory, Braga/Guimarães, Portugal 3 REQUIMTE/Laboratório de Farmacognosia, Departamento de Química, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade do Porto, R. Jorge Viterbo Ferreira, Porto, Portugal ABSTRACT The phylum Echinodermata constitutes a successful and widespread group comprising Asteroidea, Ophiuroidea, Echinoidea, Holothuroidea and Crinodeia. Nowadays, marine organisms are being given a lot of attention in drug discovery pipelines. In these studies, sponges and nudibranchs are frequently addressed, however an increasing number of * Corresponding author - DMP: [email protected] 2 David M. Pereira, Paula B. Andrade, Ricardo A. Pires, et al. works focus their attention in echinoderms. Given the fact that many of the bioactive molecules found in echinoderms are diet-derived, different feeding behavior and surrounding environment plays a critical role in the chemical composition of echinoderms. In this work, the most relevant chemical classes of small molecules present in echinoderms, such as fatty acids, carotenoids and sterols will be addressed. When data is available, the influence of the environment on the chemical profile of these organisms will be discussed. Keywords: Echinoderms; fatty acids; carotenoids; sterols. INTRODUCTION Marine environment remains, nowadays, the most diversified ecosystem on Earth as well as the least studied one. -

The Echinoderm Fauna of Turkey with New Records from the Levantine Coast of Turkey

Proc. of middle East & North Africa Conf. For Future of Animal Wealth THE ECHINODERM FAUNA OF TURKEY WITH NEW RECORDS FROM THE LEVANTINE COAST OF TURKEY Elif Özgür1, Bayram Öztürk2 and F. Saadet Karakulak2 1Faculty of Fisheries, Akdeniz University, TR-07058 Antalya, Turkey 2İstanbul University, Faculty of Fisheries, Ordu Cad.No.200, 34470 Laleli- Istanbul, Turkey Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The echinoderm fauna of Turkey consists of 80 species (two Crinoidea, 22 Asteroidea, 18 Ophiuroidea, 20 Echinoidea and 18 Holothuroidea). In this study, seven echinoderm species are reported for the first time from the Levantine coast of Turkey. These are, five ophiroid species; Amphipholis squamata, Amphiura chiajei, Amphiura filiformis, Ophiopsila aranea, and Ophiothrix quinquemaculata and two echinoid species; Echinocyamus pusillus and Stylocidaris affinis. Turkey is surrounded by four seas with different hydrographical characteristics and Turkish Straits System (Çanakkale Strait, Marmara Sea and İstanbul Strait) serve both as a biological corridor and barrier between the Aegean and Black Seas. The number of echinoderm species in the coasts of Turkey also varies due to the different biotic environments of these seas. There are 14 echinoderm species reported from the Black Sea, 19 species from the İstanbul Strait, 51 from the Marmara Sea, 71 from the Aegean Sea and 42 from the Levantine coasts of Turkey. Among these species, Asterias rubens, Ophiactis savignyi, Diadema setosum, and Synaptula reciprocans are alien species for the Turkish coasts. Key words: Echinodermata, new records, Levantine Sea, Turkey. Cairo International Covention Center , Egypt , 16 - 18 – October , (2008), pp. 571 - 581 Elif Özgür et al. -

Decapoda Natantia, Pontoniinae)

<T / L PERICLIMENER COLEMANI SP. NOV., A NEW SHRIMP ASSOCIATE OF A RARE SEA URCHIN FROM HERON ISLAND, QUEENSLAND (DECAPODA NATANTIA, PONTONIINAE) by A. J. BRUCE RECORDS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Vol. 29, No. 18: Pages 485-502 Figures 1-8 SYDNEY 6th June, 1975 Price, 50c Printed by Order of the Trustees Rec. Aust. Mus., 29. page 485. 78318-A Fig. !.—Pcriclimenes colemani sp. nov. Ovigerous female allotype. 487 Periclimenes colemani sp. nov., a new shrimp associate of a rare sea urchin from Heron Island, Queensland (Decapoda Natantia, Pontoniinae) A. J. BRUCE Hast African Marine Fisheries Research Organization P.O. Box 81651, Mombasa, Kenya Figures 1-8. Manuscript received I::t lanunry, 1974. Manuscript revised 16th June, 1974. SUMMARY Periclimenes colemani, a new species of pontoniinid shrimp, is described and illustrated. This species was found at Heron Island on the Australian Great Barrier Reef. It lives in pairs on the test of the sea urchin Asthenosoma intermedium H. L. Clark. The new species is considered to occupy a rather isolated systematic position, most closely related to another echinoid associate, P. hirsutus Bruce. It is also remarkable for its cryptic white, red spotted colour pattern. The associations between Indo-West Pacific Periclimenes spp, and echinoids are briefly reviewed. INTRODUCTION The association of echinoderms with many species of the large pon- toniinid genus Periclimenes Costa, has been well established for many years but relatively few species have been found to occur in associations with echinoids. The first species to be reported as an echinoid associate was Periclimenes maldivensis Bruce, by Borradaile, (1915, as P.