UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Lang Freer and His Gallery of Art : Turn-Of-The-Century Politics and Aesthetics on the National Mall

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2007 Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall. Patricia L. Guardiola University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Guardiola, Patricia L., "Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 543. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/543 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements F or the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Fine Arts University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2007 CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Approved on June 8, 2007 By the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director ii DEDICATION In memory of my grandfathers, Mr. -

Sadakichi and America

art credit rule should be: if on side, then in gutter. if underneath, then at same baseline as text page blue line, raise art image above it. editorial note editorial note THOMAS obody called him Carl, the name he shared with CHRISTENSEN his father, Carl Herman Oskar Hartmann. To N Walt Whitman he was “that Japanee.” To W. C. Fields he was “Catch-a-Crotchie,” “Itchy-Scratchy,” or “Hoochie-Coochie.” To the critic James Gibbons Huneker Sadakichi he was “a fusion of Jap and German, the ghastly experi- ment of an Occidental on the person of an Oriental,” and and America years later John Barrymore would call him “a living freak presumably sired by Mephistopheles out of Madame But- A case of terfy.” A 1916 magazine profle (calling him “our weirdest poet”) insisted he was “much more Japanese than Ger- taken identity man.” During World War II, because of his Japanese and German heritage, he was accused of being a spy, and he barely escaped internment. More recently, in 1978, schol- ars Harry W. Lawton and George Knox, in their intro- After all, not to create only, or found only, duction to his selected photography criticism, The Valiant But to bring, perhaps from afar, Knights of Daguerre, presented him as “Sadakichi Hart- what is already founded, mann (1867–1944), the Japanese-German writer and critic.” To give it our own identity, average, limitless, free; And so Hartmann is usually introduced, as if his ethnicity To fll the gross, the torpid bulk were the most important thing about him. But despite his with vital religious fre; ancestry Carl Sadakichi Hartmann was not Japanese or Not to repel or destroy, so much as German—he was an American. -

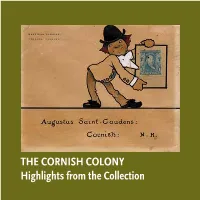

The Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection the Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection

THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection The Cornish Colony, located in the area of Cornish, New The Cornish Colony did not arise all of apiece. No one sat down at Hampshire, is many things. It is the name of a group of artists, a table and drew up plans for it. The Colony was organic in nature, writers, garden designers, politicians, musicians and performers the individual members just happened to share a certain mind- who gathered along the Connecticut River in the southwest set about American culture and life. The lifestyle that developed corner of New Hampshire to live and work near the great from about 1883 until somewhere between the two World Wars, American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Colony is also changed as the membership in the group changed, but retained a place – it is the houses and landscapes designed in a specific an overriding aura of cohesiveness that only broke down when the Italianate style by architect Charles Platt and others. It is also an country’s wrenching experience of the Great Depression and the ideal: the Cornish Colony developed as a kind of classical utopia, two World Wars altered American life for ever. at least of the mind, which sought to preserve the tradition of the —Henry Duffy, PhD, Curator Academic dream in the New World. THE COLLECTION Little is known about the art collection formed by Augustus Time has not been kind to the collection at Aspet. Studio fires Saint-Gaudens during his lifetime. From inventory lists and in 1904 and 1944 destroyed the contents of the Paris and New correspondence we know that he had a painting by his wife’s York houses in storage. -

"GWIKS Lecture Series: Charles Lang Freer and the Collecting of Korean Art in the Early 20Th Century”

GWIKS Lecture Series Thursday Mar. 8, 2018 "GWIKS Lecture Series: Charles Lang Freer and the Collecting of Korean Art in the Early 20th Century” Charlotte Horlyck Smithsonian Institution Senior Fellow of Art History at the Freer|Sackler 2:00 – 3:30 PM Elliott School of International Affairs Room 503 The George Washington University 1957 E St. NW, Washington, DC 20052 ABOUT THE TALK This talk centers on the Korean collection of Charles Lang Freer (1854-1919), founder of the Smithsonian Institution's Freer Gallery of Art. Freer was a pioneering individual whose collection of Western and Asian art was among the most extensive of its time. This includes his collection of Korean artifact, which he began to acquire in 1896, culminating in around 450 objects, which are now housed in the Freer Gallery. The collection is significant not only for its quality and size, but because it exemplifies the rising interest in Korean art around the turn of the twentieth century. In the exploration of Freer's Korean pieces, some of the core issues that impacted and shaped the collecting of Korean art during this time will be addressed, including the availability of antiques, the development of scholarship on Korean cultural heritage, individual and institutional motivations for collecting Korean art, among other questions. SPEAKER Charlotte Horlyck was appointed Lecturer in Korean Art History at SOAS in 2007 and served as Chair of its Centre of Korean Studies from 2013 to 2017. Prior to taking up her position at SOAS, she curated the Korean collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. -

Ann C. Gunter

Ann C. Gunter Bertha and Max Dressler Professor in the Humanities Professor of Art History, Classics, and in the Humanities Northwestern University Mailing address: Department of Art History 1800 Sherman Ave., Suite 4400 Evanston, IL 60201 Voice mail 847 467-0873 e-mail: [email protected] Education 1980 Columbia University Ph.D. 1976 Columbia University M.Phil. 1975 Columbia University M.A. 1973 Bryn Mawr College A.B. magna cum laude with departmental honors Professional Employment Bertha and Max Dressler Professor in the Humanities, Northwestern University, 2013– Professor of Art History, Classics, and in the Humanities, Northwestern University, 2008– Head of Scholarly Publications and Programs, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2004–08 Assistant Curator of Ancient Near Eastern Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution (1987–92); Associate Curator (1992–2004); Curator (2004–08) Visiting Assistant Professor, Art History Department, Emory University, Atlanta (1986–87) Visiting Assistant Professor, Departments of Art History and Classics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (1981–85) Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley (Winter– Spring 1981) Director, American Research Institute in Turkey at Ankara (1978–79) Fellowships, Grants, and Awards Visiting Professor (Directrice d’études), École Pratique des Hautes Études, University of Paris (lecture series to be presented in May 2016) Fritz Thyssen Stiftung 2000–01 -

American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works 43Rd

Egyptian Glass at the Freer Gallery of Art American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works 43rd Annual Meeting, May 13-16, 2015 Ellen Nigro, Ellen Chase, Blythe McCarthy Department of Conservation and Scientific Research, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution In 1909, Charles Lang Freer bought a collection of 1,388 ancient glass beads, vessels, and mosaic fragments in Cairo, Egypt from the antiquities dealer Giovanni Dattari. The objects are primarily XVIII Dynasty, Ptolemaic and Roman period Egyptian pieces, as well as many later Venetian and Islamic fragments. Although the collection varies in geographic origin and time period, all the pieces are colorful examples of fine craftsmanship, from intricate millifiori inlays to cast amulets and larger vessels. Until 2013, the collection was largely left unstudied and was inappropriately stored. As a result, the Department of Conservation and Scientific Research at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery is rehousing and researching the collection. This poster will focus on the storage project and the challenges associated with rehousing a large collection of small objects while touching on the historical and technical research. Technical Analysis The purpose of the technical study is to characterize the materials and techniques of the collection and to sort Research in the Freer Gallery Archives some of the objects by time and place according to the technical data. This study included the following techniques: Mr. Freer travelled to Egypt several times between • x-radiography of the vessels to assess the manufacture techniques 1907 and 1909, where he purchased this collection • qualitative x-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy to analyze lead content and colorants on a large number of of glass, as well as a number of faience pieces, objects within the collection manuscripts, and funerary objects. -

Elias Goldensky: Wizard of Photography' Gary D

Elias Goldensky: Wizard of Photography' Gary D. Saretzky Who would not, out of sheer vanity, like to have himself photographed by ... Elias Goldensky ... ? Sidney Allan [Sadakichi Hartmann], 1904 In June 1924, Elias Goldensky (1867-1943) traveled from his Philadel- phia studio to demonstrate his portrait photography technique at the Con- vention of the Ontario Society of Photographers in Toronto. To encourage attendance, the Society printed a publicity card with Goldenskys portrait. The text on the back reflects the esteem with which Goldensky was held by his professional colleagues: Mr. Elias Goldensky, the Wizard of Photography, is coming from Philadelphia to demonstrate at our convention .... He has dem- onstrated at Conventions perhaps more than any other living pho- tographer. He is a most interesting lecturer and has the great gift of being a natural teacher; he can, and will, solve your many light- ing problems. He will show how to so balance a lighting that he can light four subjects at opposite corners at one time, clever as this may be in its practical way; he will also demonstrate how to make pictorial work. He is an acknowledged artist, in addition to. his practical craftsmanship. Three Big Performances from the brain of this marvelous workman. You owe it to yourself to see and hear him. .2 The wizard did not disappoint his audience. As reported by the Toronto Star Weekly on June 28 under the headline, "King of the Camera Works Like Greased Lightning," Goldensky, described as "one of the six best in the coun- try," took 400 portraits in 55 minutes while keeping up an amusing running commentary: "Good morning, madam," he began, "in the ma-ter of portraits we have two sizes, one at six photos for twenty dollars, one at six for forty. -

Mixed Race Capital: Cultural Producers and Asian American Mixed Race Identity from the Late Nineteenth to Twentieth Century

MIXED RACE CAPITAL: CULTURAL PRODUCERS AND ASIAN AMERICAN MIXED RACE IDENTITY FROM THE LATE NINETEENTH TO TWENTIETH CENTURY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Stacy Nojima Dissertation Committee: Vernadette V. Gonzalez, Chairperson Mari Yoshihara Elizabeth Colwill Brandy Nālani McDougall Ruth Hsu Keywords: Mixed Race, Asian American Culture, Merle Oberon, Sadakichi Hartmann, Winnifred Eaton, Bardu Ali Acknowledgements This dissertation was a journey that was nurtured and supported by several people. I would first like to thank my dissertation chair and mentor Vernadette Gonzalez, who challenged me to think more deeply and was able to encompass both compassion and force when life got in the way of writing. Thank you does not suffice for the amount of time, advice, and guidance she invested in me. I want to thank Mari Yoshihara and Elizabeth Colwill who offered feedback on multiple chapter drafts. Brandy Nālani McDougall always posited thoughtful questions that challenged me to see my project at various angles, and Ruth Hsu’s mentorship and course on Asian American literature helped to foster my early dissertation ideas. Along the way, I received invaluable assistance from the archive librarians at the University of Riverside, University of Calgary, and the Margaret Herrick Library in the Beverly Hills Motion Picture Museum. I am indebted to American Studies Department at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa for its support including the professors from whom I had the privilege of taking classes and shaping early iterations of my dissertation and the staff who shepherded me through the process and paperwork. -

Direct PDF Link for Archiving

Kathleen Pyne On Women and Ambivalence in the Evolutionary Topos Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 2, no. 2 (Spring 2003) Citation: Kathleen Pyne, “On Women and Ambivalence in the Evolutionary Topos,” Nineteenth- Century Art Worldwide 2, no. 2 (Spring 2003), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/ spring03/225-on-women-and-ambivalence-in-the-evolutionary-topos. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2003 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Pyne: On Women and Ambivalence in the Evolutionary Topos Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 2, no. 2 (Spring 2003) On Women and Ambivalence in the Evolutionary Topos by Kathleen Pyne In the decade following the Civil War evolutionary theory shook the foundations of America's self-identity as God's chosen people. On the one hand, Charles Darwin brought the scrutiny of positivist science to bear on biological issues, negating any human uniqueness, while on the other, Herbert Spencer translated evolution into a philosophy of human progress. Spencer's evolutionary philosophy, in particular, had a tremendous impact in the United States because it reconciled the new science with traditional beliefs; it preserved the belief in the special spiritual nature of humankind, as well as the existence of a spiritual realm. The purposefulness of human life on earth thus was upheld, in contrast to Darwin's negation of any human uniqueness. But as Gillian Beer has pointed out, evolutionary science abounded in metaphors and contradictory elements; it could be read as both an ascent and a descent of man. -

Charles Lang Freer and Indian Art

THE FREER HOUSE 71 East Ferry, Detroit, MI 48202 An International Landmark... A World Class Lecture Series 313-664-2500 From Traveler to Aesthete: Charles Lang Freer and Indian Art by Brinda Kumar, PhD Assistant Curator Department of Modern and Contemporary Art Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY Sunday, June 4, 2017, 2:00 pm LECTURE Detroit Institute of Arts Marvin and Betty Danto Lecture Hall FREE with DIA admission 3:30-5 PM Reception & Tours Freer House 71 East Ferry Street, Detroit $10 General Admission Zayn al’-’Abidin $5 Students Artist Hanuman returns the $5 FAAC or Freer House Members mountain with the (pay at the door) four healing plants to the Himalayas. Co-Sponsor Folio from the Ramayana of Valmiki, Friends of Asian Arts & Cultures (FAAC), DIA vol. 2., South Asian, Mughal period, For information contact Rose Foster at: late 16th century, Freer Gallery of Art 313-664-2509 or [email protected] Detroit industrialist Charles Lang Freer’s passion for In- U.S. earlier that year, while his itinerary was in keeping with dia influenced the formation of one of the finest early col- similar travels by other American collectors such as Isabella lections of Asian art in America. Freer’s visionary aesthetic Stewart Gardner. ideas positioned Indian art as “fine art” in an era when it Although he visited India only once, Freer would con- was largely relegated in the West to being of only ethno- sider Indian art and culture to be “an important link in the graphic or decorative interest. chain” as he developed a collection of Asian and Near East- When Freer planned his first trip to Asia in 1894, his ern art. -

Rose Standish Nichols and the Cornish Art Colony

Life at Mastlands: Rose Standish Nichols and the Cornish Art Colony Maggie Dimock 2014 Julie Linsdell and Georgia Linsdell Enders Research Intern Introduction This paper summarizes research conducted in the summer of 2014 in pursuit of information relating to the Nichols family’s life at Mastlands, their country home in Cornish, New Hampshire. This project was conceived with the aim of establishing a clearer picture of Rose Standish Nichols’s attachment to the Cornish Art Colony and providing insight into Rose’s development as a garden architect, designer, writer, and authority on garden design. The primary sources consulted consisted predominantly of correspondence, diaries, and other personal ephemera in several archival collections in Boston and New Hampshire, including the Nichols Family Papers at the Nichols House Museum, the Rose Standish Nichols Papers at the Houghton Library at Harvard University, the Papers of the Nichols-Shurtleff Family at the Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute, and the Papers of Augustus Saint Gaudens, the Papers of Maxfield Parrish, and collections relating to several other Cornish Colony artists at the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College. After examining large quantities of letters and diaries, a complex portrait of Rose Nichols’s development emerges. These first-hand accounts reveal a woman who, at an early age, was intensely drawn to the artistic society of the Cornish Colony and modeled herself as one of its artists. Benefitting from the influence of her famous uncle Augustus Saint Gaudens, Rose was given opportunities to study and mingle with some of the leading artistic and architectural luminaries of her day in Cornish, Boston, New York, and Europe. -

Sadakichi Hartmann and Yone Noguchi

Smith ScholarWorks English Language and Literature: Faculty Publications English Language and Literature 5-23-2019 Strategic Hybridity in Early Chinese and Japanese American Literature Floyd Cheung Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/eng_facpubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cheung, Floyd, "Strategic Hybridity in Early Chinese and Japanese American Literature" (2019). English Language and Literature: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/eng_facpubs/12 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literature: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] Strategic Hybridity in Early Chinese and Japanese American Literature Floyd Cheung, Department of English Language and Literature, Smith College https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.909 Published online: 23 May 2019 Summary Early Chinese and Japanese American male writers between 1887 and 1938 such as Yan Phou Lee, Yung Wing, Sadakichi Hartmann, Yone Noguchi, and H. T. Tsiang accessed dominant US publishing markets and readerships by presenting themselves and their works as cultural hybrids that strategically blended enticing Eastern content and forms with familiar Western language and structures. Yan Phou Lee perpetrated cross-cultural comparisons that showed that Chinese were not unlike Europeans and Americans. Yung Wing appropriated and then transformed dominant American autobiographical narratives to recuperate Chinese character. Sadakichi Hartmann and Yone Noguchi combined poetic traditions from Japan, Europe, and America in order to define a modernism that included cosmopolitans such as themselves. And H. T. Tsiang promoted Marxist world revolution by experimenting with fusions of Eastern and Western elements with leftist ideology.