American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works 43Rd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Lang Freer and His Gallery of Art : Turn-Of-The-Century Politics and Aesthetics on the National Mall

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2007 Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall. Patricia L. Guardiola University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Guardiola, Patricia L., "Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 543. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/543 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements F or the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Fine Arts University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2007 CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Approved on June 8, 2007 By the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director ii DEDICATION In memory of my grandfathers, Mr. -

"GWIKS Lecture Series: Charles Lang Freer and the Collecting of Korean Art in the Early 20Th Century”

GWIKS Lecture Series Thursday Mar. 8, 2018 "GWIKS Lecture Series: Charles Lang Freer and the Collecting of Korean Art in the Early 20th Century” Charlotte Horlyck Smithsonian Institution Senior Fellow of Art History at the Freer|Sackler 2:00 – 3:30 PM Elliott School of International Affairs Room 503 The George Washington University 1957 E St. NW, Washington, DC 20052 ABOUT THE TALK This talk centers on the Korean collection of Charles Lang Freer (1854-1919), founder of the Smithsonian Institution's Freer Gallery of Art. Freer was a pioneering individual whose collection of Western and Asian art was among the most extensive of its time. This includes his collection of Korean artifact, which he began to acquire in 1896, culminating in around 450 objects, which are now housed in the Freer Gallery. The collection is significant not only for its quality and size, but because it exemplifies the rising interest in Korean art around the turn of the twentieth century. In the exploration of Freer's Korean pieces, some of the core issues that impacted and shaped the collecting of Korean art during this time will be addressed, including the availability of antiques, the development of scholarship on Korean cultural heritage, individual and institutional motivations for collecting Korean art, among other questions. SPEAKER Charlotte Horlyck was appointed Lecturer in Korean Art History at SOAS in 2007 and served as Chair of its Centre of Korean Studies from 2013 to 2017. Prior to taking up her position at SOAS, she curated the Korean collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. -

Ann C. Gunter

Ann C. Gunter Bertha and Max Dressler Professor in the Humanities Professor of Art History, Classics, and in the Humanities Northwestern University Mailing address: Department of Art History 1800 Sherman Ave., Suite 4400 Evanston, IL 60201 Voice mail 847 467-0873 e-mail: [email protected] Education 1980 Columbia University Ph.D. 1976 Columbia University M.Phil. 1975 Columbia University M.A. 1973 Bryn Mawr College A.B. magna cum laude with departmental honors Professional Employment Bertha and Max Dressler Professor in the Humanities, Northwestern University, 2013– Professor of Art History, Classics, and in the Humanities, Northwestern University, 2008– Head of Scholarly Publications and Programs, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2004–08 Assistant Curator of Ancient Near Eastern Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution (1987–92); Associate Curator (1992–2004); Curator (2004–08) Visiting Assistant Professor, Art History Department, Emory University, Atlanta (1986–87) Visiting Assistant Professor, Departments of Art History and Classics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (1981–85) Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley (Winter– Spring 1981) Director, American Research Institute in Turkey at Ankara (1978–79) Fellowships, Grants, and Awards Visiting Professor (Directrice d’études), École Pratique des Hautes Études, University of Paris (lecture series to be presented in May 2016) Fritz Thyssen Stiftung 2000–01 -

Charles Lang Freer and Indian Art

THE FREER HOUSE 71 East Ferry, Detroit, MI 48202 An International Landmark... A World Class Lecture Series 313-664-2500 From Traveler to Aesthete: Charles Lang Freer and Indian Art by Brinda Kumar, PhD Assistant Curator Department of Modern and Contemporary Art Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY Sunday, June 4, 2017, 2:00 pm LECTURE Detroit Institute of Arts Marvin and Betty Danto Lecture Hall FREE with DIA admission 3:30-5 PM Reception & Tours Freer House 71 East Ferry Street, Detroit $10 General Admission Zayn al’-’Abidin $5 Students Artist Hanuman returns the $5 FAAC or Freer House Members mountain with the (pay at the door) four healing plants to the Himalayas. Co-Sponsor Folio from the Ramayana of Valmiki, Friends of Asian Arts & Cultures (FAAC), DIA vol. 2., South Asian, Mughal period, For information contact Rose Foster at: late 16th century, Freer Gallery of Art 313-664-2509 or [email protected] Detroit industrialist Charles Lang Freer’s passion for In- U.S. earlier that year, while his itinerary was in keeping with dia influenced the formation of one of the finest early col- similar travels by other American collectors such as Isabella lections of Asian art in America. Freer’s visionary aesthetic Stewart Gardner. ideas positioned Indian art as “fine art” in an era when it Although he visited India only once, Freer would con- was largely relegated in the West to being of only ethno- sider Indian art and culture to be “an important link in the graphic or decorative interest. chain” as he developed a collection of Asian and Near East- When Freer planned his first trip to Asia in 1894, his ern art. -

After Whistler: the Artist & His Influence on American Painting

LINDA MERRILL Emory University Art History Department Atlanta, Georgia 30322 404.727-0514 [email protected] Education University of London (University College), England PhD, History of Art, 1985 Dissertation: “The Diffusion of Aesthetic Taste: Whistler and the Popularization of Aestheticism, 1875– 1881.” Advisor: William H. T. Vaughan. Marshall Scholarship, 1981–84, awarded by the Marshall Plan Commemoration Commission of Great Britain for postgraduate study. Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts AB, English, 1981. Summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, with Highest Honors in English, 1981. Employment Emory University, Atlanta Senior Lecturer and Director of Undergraduate Studies in Art History, Fall 2016—present Lecturer and Director of Undergraduate Studies in Art History, Fall 2013-16 Freer Gallery of Art/Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Guest curator, with Dr. Robyn Asleson, of The Lost Symphony: Whistler and the Perfection of Art, January 16— May 30, 2016. Global Fine Art Award for Best Thematic Impressionist/Modern Exhibition 2016. National Endowment for the Humanities, Office of the Chairman, Washington, D.C. Humanities Administrator, November 2006–April 2007 (temporary appointment). High Museum of Art, Atlanta Margaret and Terry Stent Curator of American Art, 1998–2000 Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Curator of American Art, 1997–98; Associate Curator of American Art, 1990–97; Assistant Curator of American Art, 1985–90. Hood College, Frederick, Maryland, Department of Art History Visiting Assistant Professor in Art History, Spring 1991, 1985–86. Publications Books After Whistler: The Artist & His Influence on American Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press and the High Museum of Art, 2003. -

Freer and Swami Vivekananda: Detroit and India

Freer and Swami Vivekananda: Detroit and India An exhibit from the historic Charles Lang Freer House, Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute, Wayne State University Image of Swami Vivekananda appears courtesy of Charles Lang Freer, 1909. Indies Services, Bhavnagar, Gujarat, India. Portrait by Alvin Langdon Coburn c. 1893. Freer Gallery of Art Archives, Smithsonian Institution. THE FREER HOUSE 71 E. Ferry Street, Detroit MI, 48202 | 313-664-2500 | www.mpsi.wayne.edu/freer/ Use or reproduction by permission only from The Freer House, Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute, Wayne State University. PHOTOS BY ALEXANDER VERTIKOFF THE FREER HOUSE The Freer House is considered to be one of the most important historic buildings in Michigan with its outstanding archi- tecture and history as “the original Freer Gallery of Art.” Today, parts of the building continue to serve as offices for child and family development faculty of the Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute/WSU, while major sections of the house serve as space for visitors, meetings and events. The Freer House features quarter-sawn oak paneling, built in cabinets and seating, and ornate decorative light fixtures and hardware. Reproductions of 11 paintings by the American artists, Dewing, Tryon and Thayer, have recently been installed in their original locations. Restoration goals include the revitalization of Freer’s historic courtyard gardens, restoration of the 1906 Whistler Gallery as an exhibition and meeting space, and creation of a public welcome and interpretative center for visitors in the former carriage house. Use or reproduction by permission only from The Freer House, Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute, Wayne State University. Freer and Swami Vivekananda Detroit and India Meghan Urisko, 2013 Research Kailey McAlpin, 2017 Research Catherine Blasio, Exhibit Designer William S. -

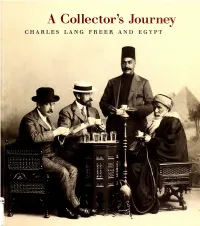

A Collector's Journey : Charles Lang Freer and Egypt / Ann C

A Collector's Journ CHARLES LANG FREER AND EGYPT A Collector's Journey "I now feel that these things are the greatest art in the world," wrote Charles Lang Freer, to a close friend. ". greater than Greek, Chinese or Japanese." Surprising words from the man who created one of the finest collections of Asian art at the turn of the century and donated the collection and funds to the Smithsonian Institution for the construction of the museum that now bears his name, the Freer Gallery of Art. But Freer (1854-1919) became fascinated with Egyptian art during three trips there, between 1906 and 1909, and acquired the bulk of his collection while on site. From jewel-like ancient glass vessels to sacred amulets with supposed magical properties to impressive stone guardian falcons and more, his purchases were diverse and intriguing. Drawing on a wealth of unpublished letters, diaries, and other sources housed in the Freer Gallery of Art Archives, A Collectors Journey documents Freer's expe- rience in Egypt and discusses the place Egyptian art occupied in his notions of beauty and collecting aims. The author reconstructs Freer's journeys and describes the often colorful characters—collectors, dealers, schol- ars, and artists—he met on the way. Gunter also places Freer's travels and collecting in the broader context of American tourism and interest in Egyptian antiquities at the time—a period in which a growing number of Americans, including such financial giants as J. Pierpont Morgan and other Gilded Age barons, were collecting in the same field. A Collector's Journey CHARLES LANG FREER AND EGYPT A Collector's Journey CHARLES LANG FREER AND EGYPT ) Ann C. -

Guidelines and Procedures for World War II Provenance Issues

Guidelines and Procedures for World War II Provenance Issues The Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC September 2009 2 The Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Smithsonian Institution September 2009 Guidelines and Procedures for World War II Provenance Issues Chapter 1: Introduction and Historical Context 3 Chapter 2: Guidelines for Existing Collections 5 Chapter 3: Guidelines for Acquisitions 22 Chapter 4: Guidelines for Incoming Loans 47 Chapter 5: World War II Provenance Research 61 Chapter 6: Online Display Procedures and Guidelines 85 Appendix A: Washington Conference Principles on Nazi- Confiscated Art (1998) 101 Appendix B: American Association of Museums Guidelines Concerning the Unlawful Appropriation of Objects During the Nazi Era, Approved, November 1999, Amended, April 2001 102 Appendix C: Report of the AAMD Task Force on the Spoliation of Art during the Nazi/World War II Era (1933-1945) (June 4, 1998) 107 Appendix D: Smithsonian Institution SD 600 Implementation Manual 111 Appendix E: AAM Recommended Procedures for Providing Information to the Public about Objects Transferred in Europe during the Nazi Era 116 Appendix F: AAMD Guidelines for Acquisition of Archaeological Material and Ancient Art 120 Appendix G: Looted Art Bibliography 126 3 Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Context The World War II Era (1933-1945) and Recent Events During the tumultuous years before and during World War II, the Nazi regime and their collaborators orchestrated a system of confiscation, coercive transfer, looting and destruction of cultural objects in Europe on an unprecedented scale. Millions of art objects and other cultural items were unlawfully and often forcibly removed from their rightful owners. -

THE NEW: Modern, Modernity, Modernism 22ND ANNUAL AMERICAN ART CONFERENCE

Initiatives in Art and Culture THE NEW: Modern, Modernity, Modernism 22ND ANNUAL AMERICAN ART CONFERENCE FRIDAY – SATURDAY, MAY 19 – 20, 2017 Art, Washington, D.C. Art, Washington, cm). The National Gallery of × 108 84.5 × 42.5 in. (215 1862, Oil on canvas, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Ralph Albert Blakelock, Seascape, Oil on board laid down on board, 7⅞ x 11¾ in. Private collection. Photo, courtesy Questroyal Fine Art, LLC, New York, New York. Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire: The Consummation of Empire, 1836, Oil on canvas, 51 x 76 in. Collection of The New-York Historical Society. Marsden Hartley, Canuck Yankee Lumberjack at Old Orchard Beach, Maine, 1940–41, Oil on Masonite- type hardboard, 40 1/8 × 30 in. (101.9 × 76.2 cm). Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution. THE NEW: Modern, Modernity, Modernism 22ND ANNUAL AMERICAN ART CONFERENCE Modern, modernity, Modernism: the significance of these terms changes as society, language, and perception change. Thomas Cole was modern in 1824; by 1862, one could argue, his most prominent successor, Frederic Edwin Church was not, as comparison of Church’s Cotopaxi to Whistler’s contemporaneous Symphony in White, No 1: The White Girl reveals. By the 1950s, both of these works would seem dated. Art of the early and mid-20th century from movements once considered radical can now seem staid and conventional, particularly when juxtaposed with works from the late 20th- and early 21st-centuries. Alfred H. Maurer, Fauve Still Life, ca. 1908-10, Oil on canvas, 18 x 21 5/8 in. -

Second Presentation of the Charles Lang Freer Medal

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION FREER GALLERY OF ART PRESENTATION of the CHARLES LANG FREER MEDAL to PROFESSOR ERNST KÜHNEL Washington, D. C. May 3, 1960 FREER GALLERY OF ART Smithsonian Institution SECOND PRESENTATION of the CHARLES LANG FREER MEDAL PROFESSOR ERNST KUHNEL Washington, D. C. May 3, 1960 Freer Gallery of Art lashinton D. C. FOREWORD On February 25, 1956, occurred the one-hundredth anniversary of the birth of the late Charles Lang Freer, who founded the Freer Gallery of Art. To mark this occasion, a medal was established in his memory and presented to Professor Osvald Siren of Stockholm, Sweden, before some 300 guests in the auditorium of the Gallery. On May 3, 1960, the second Charles Lang Freer Medal was presented to Professor Ernst Kuhnel of Ber lin, Germany, before 325 guests in the Gallery auditor- 1um.• On the rostrum were His Excellency Mr. Ardeshir Zahedi, Ambassador of Iran, Mr. Franz Krapf, Minister of Germany, Professor Ernst Kuhnel, Dr. Richard Et tinghausen, Curator of Near EasternArt, Freer Gallery of, Art, and Dr. Leonard Carmichael, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. On the following pages will be found the program and exercises accompanying the presentation. A. G. WENLEY Director Freer Gallery of Art Washington, D. C. May, 1960 ••• SECOND PRESENTATION of the CHARLES LANG FREER. MEDAL May 3, 1960 Opening Remarks LEONARD CARMICHAEL Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution PROFESSOR KUHNEL'S SCHOLARLY ACIDEVEMENTS Richard Ettinghausen Curator, Near Eastern Art Freer Gallery of Art PRESENTATION by The Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution ADDRESS OF ACCEPTANCE Professor Ernst Kühnel FOLLOWING 'l'HE ADDRESS OF ACCEPTANCE RECEPTION IN GALLERY 17 V OPENING REMARKS. -

Making “Chinese Art”: Knowledge and Authority in the Transpacific Progressive Era

Making “Chinese Art”: Knowledge and Authority in the Transpacific Progressive Era Kin-Yee Ian Shin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Kin-Yee Ian Shin All rights reserved ABSTRACT -- Making “Chinese Art”: Knowledge and Authority in the Transpacific Progressive Era Kin-Yee Ian Shin This dissertation presents a cultural history of U.S.-China relations between 1876 and 1930 that analyzes the politics attending the formation of the category we call “Chinese art” in the United States today. Interest in the material and visual culture of China has influenced the development of American national identity and shaped perceptions of America’s place in the world since the colonial era. Turn-of-the-century anxieties about U.S.-China relations and geopolitics in the Pacific Ocean sparked new approaches to the collecting and study of Chinese art in the U.S. Proponents including Charles Freer, Langdon Warner, Frederick McCormick, and others championed the production of knowledge about Chinese art in the U.S. as a deterrent for a looming “civilizational clash.” Central to this flurry of activity were questions of epistemology and authority: among these approaches, whose conceptions and interpretations would prevail, and on what grounds? American collectors, dealers, and curators grappled with these questions by engaging not only with each other—oftentimes contentiously—but also with their counterparts in Europe, China, and Japan. Together they developed and debated transnational forms of expertise within museums, world’s fairs, commercial galleries, print publications, and educational institutes. -

In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000 (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2006)

92 Book Reviews / Novum Testamentum 50 (2008) 81-96 Michelle P. Brown (ed.), In the Beginning: Bibles before the Year 1000 (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2006). 360 pp. ISBN 0934868037 (paperback), $24.95 . Larry W. Hurtado (ed.), Th e Freer Biblical Manuscripts: Fresh Studies on an American Treasure Trove (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2006), x + 308 pp. ISBN 1589832086 $34.95, (= Text Critical Studies 6). Scot McKendrick, In a Monastery Library: Preserving Codex Sinaiticus and the Greek Written Heritage (London: Th e British Library), 48 pp. ISBN 0712349405, ₤6.95. In the Beginning: Bibles before the Year 1000 is an outstanding and attrac- tive introduction to and catalogue of an exhibition held at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in association with the Freer Gallery of Art and the Bodle- ian Library, Oxford from October 2006 to January 2007. Th e book (10 1/2 inches × 9 1/2) is lavishly illustrated throughout and also contains seventy- four full colour plates. Th e whole has been published to a very high profes- sional standard, and our thanks are extended to the editors, contributors and publishers. Th e exhibition marked the centenary of Charles Lang Freer’s visit to Egypt in 1906, where he purchased his first biblical manuscripts, which are now housed in the Freer Gallery. Th e Washington Codex of the Four Gospels (variously known as the Freer Gospels, Codex Washington(i)ensis or Codex Washingtonianus) is the most famous text. Among the others are the Washington Codex of Deuteronomy and Joshua, the Washington Manuscript of the Pauline Epistles, the Coptic Psalter, the Washington Codex of the Psalms, and the Washington Codex of the Minor Prophets; all were on display at the exhibition and of course figure in this catalogue.