Connoisseurship Kathleenpyne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Department of Professional Studies Studies 2004 Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De- Mythologizing of the American West Jennie A. Harrop George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac Recommended Citation Harrop, Jennie A., "Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004). Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies. Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Professional Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLING FOR REPOSE: WALLACE STEGNER AND THE DE-MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Jennie A. Camp June 2004 Advisor: Dr. Margaret Earley Whitt Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ©Copyright by Jennie A. Camp 2004 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. GRADUATE STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DENVER Upon the recommendation of the chairperson of the Department of English this dissertation is hereby accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Profess^inJ charge of dissertation Vice Provost for Graduate Studies / if H Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Charles Lang Freer and His Gallery of Art : Turn-Of-The-Century Politics and Aesthetics on the National Mall

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2007 Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall. Patricia L. Guardiola University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Guardiola, Patricia L., "Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 543. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/543 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements F or the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Fine Arts University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2007 CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Approved on June 8, 2007 By the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director ii DEDICATION In memory of my grandfathers, Mr. -

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Hart Autograph Collection, 1731-1918, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Hart Autograph Collection, 1731-1918, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Josefson Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 February 20 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Charles Henry Hart autograph collection, 1731-1918............................... 4 Series 2: Unprocessed Addition, 1826-1892 and undated..................................... 18 Charles Henry Hart autograph collection AAA.hartchar Collection -

Tiffany Memorial Windows

Tiffany Memorial Windows: How They Unified a Region and a Nation through Women’s Associations from the North and the South at the Turn of the Twentieth Century Michelle Rene Powell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master’s of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art and Design 2012 ii ©2012 Michelle Rene Powell All Rights Reserved i Table of Contents List of Illustrations i Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Old Blandford Church, American Red Cross Building, and Windows 8 The Buildings 9 The Windows in Old Blandford Church 18 The Windows in the National American Red Cross Building 18 Comparing the Window Imagery 22 Chapter 2: History of Women’s Memorial Associations 30 Ladies’ Memorial Associations 30 United Daughters of the Confederacy 34 Woman’s Relief Corps 39 Fundraising 41 Chapter 3: Civil War Monuments and Memorials 45 Monuments and Memorials 45 Chapter 4: From the Late Twentieth Century to the Present 51 What the Windows Mean Today 51 Personal Reflections 53 Endnotes 55 Bibliography 62 Illustrations 67 ii List of Illustrations I.1: Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company, Reconstruction of 1893 Tiffany Chapel 67 Displayed at the Columbian Exposition I.2: Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company advertisement, 1898 68 I.3: Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company advertisement, 1895 69 I.4: Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company advertisement, 1899 70 I.5: Tiffany Studios, Materials in Glass and Stone, 1913 71 I.6: Tiffany Studios, Tributes to Honor, 1918 71 1.1: Old Blandford Church exterior 72 1.2: Old Blandford Church interior 72 1.3: Depictions of the marble buildings along 17th St. -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

Fine Art Connoisseur

FRANK MYERS BOGGS | JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME | MAINE’S ART | RACKSTRAW DOWNES | D. JEFFREY MIMS THE PREMIER MAGAZINE FOR INFORMED COLLECTORS AUGUST 2010 $8.95 U.S. | $9.95 CAN. Volume 7, Issue 4 Reprinted with permission from: TODAY ’S MASTERS ™ 800.610.5771 or International 011-561.655.8778. M CLICK TO SUBSCRIBE Caput Mundi (Capital of the World) By D. JEFFREY MIMS GH Editor’s Note: Born in North Carolina in 1954, D. Jeffrey Mims attended the Rhode Island THE FAÇADE OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME School of Design and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. After using a grant from the Elizabeth T. Greenshields Foundation to copy masterworks in European museums, he stud - ied in Florence with the muralist Benjamin F. Long IV. For more than a decade, Mims main - tained studios in Italy and North Carolina, undertaking such major projects as a fresco for Holy Trinity Episcopal Church (Glendale Springs, NC), an altarpiece for St. David’s Episcopal Church (Baltimore), and murals for Samford University in Birmingham. In 2000, he opened Mims Studios in Southern Pines, NC, offering a multi-year course in the meth - ods and values of classical realist drawing, easel painting, and mural painting. If I could have my way in the training of young artists, I should insist upon their spending a good deal of time in the study and designing of pure ornament that they might learn how in - dependent fine design is of its content and how slight may be the connection between art and nature. — Kenyon Cox (1856-1919) The Classic Point of View: Six Lectures on Painting (1911) hat artist can visit Rome and not be impressed, if not over - W whelmed, by the magnificent monumentality of the Eter - nal City? It was here that the Renaissance matured and defined itself, demonstrating the fertility of the classical tradition and setting the model for centuries of elaborations. -

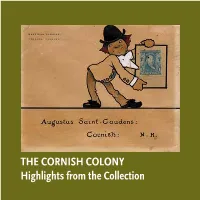

The Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection the Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection

THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection The Cornish Colony, located in the area of Cornish, New The Cornish Colony did not arise all of apiece. No one sat down at Hampshire, is many things. It is the name of a group of artists, a table and drew up plans for it. The Colony was organic in nature, writers, garden designers, politicians, musicians and performers the individual members just happened to share a certain mind- who gathered along the Connecticut River in the southwest set about American culture and life. The lifestyle that developed corner of New Hampshire to live and work near the great from about 1883 until somewhere between the two World Wars, American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Colony is also changed as the membership in the group changed, but retained a place – it is the houses and landscapes designed in a specific an overriding aura of cohesiveness that only broke down when the Italianate style by architect Charles Platt and others. It is also an country’s wrenching experience of the Great Depression and the ideal: the Cornish Colony developed as a kind of classical utopia, two World Wars altered American life for ever. at least of the mind, which sought to preserve the tradition of the —Henry Duffy, PhD, Curator Academic dream in the New World. THE COLLECTION Little is known about the art collection formed by Augustus Time has not been kind to the collection at Aspet. Studio fires Saint-Gaudens during his lifetime. From inventory lists and in 1904 and 1944 destroyed the contents of the Paris and New correspondence we know that he had a painting by his wife’s York houses in storage. -

"GWIKS Lecture Series: Charles Lang Freer and the Collecting of Korean Art in the Early 20Th Century”

GWIKS Lecture Series Thursday Mar. 8, 2018 "GWIKS Lecture Series: Charles Lang Freer and the Collecting of Korean Art in the Early 20th Century” Charlotte Horlyck Smithsonian Institution Senior Fellow of Art History at the Freer|Sackler 2:00 – 3:30 PM Elliott School of International Affairs Room 503 The George Washington University 1957 E St. NW, Washington, DC 20052 ABOUT THE TALK This talk centers on the Korean collection of Charles Lang Freer (1854-1919), founder of the Smithsonian Institution's Freer Gallery of Art. Freer was a pioneering individual whose collection of Western and Asian art was among the most extensive of its time. This includes his collection of Korean artifact, which he began to acquire in 1896, culminating in around 450 objects, which are now housed in the Freer Gallery. The collection is significant not only for its quality and size, but because it exemplifies the rising interest in Korean art around the turn of the twentieth century. In the exploration of Freer's Korean pieces, some of the core issues that impacted and shaped the collecting of Korean art during this time will be addressed, including the availability of antiques, the development of scholarship on Korean cultural heritage, individual and institutional motivations for collecting Korean art, among other questions. SPEAKER Charlotte Horlyck was appointed Lecturer in Korean Art History at SOAS in 2007 and served as Chair of its Centre of Korean Studies from 2013 to 2017. Prior to taking up her position at SOAS, she curated the Korean collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. -

1 United States Bankruptcy Court Eastern District of Michigan

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN ) ) In re ) Chapter 9 ) CITY OF DETROIT, MICHIGAN ) Case No.: 13-53846 ) Hon. Steven W. Rhodes Debtor. ) ) ) CITY OF DETROIT’S CORRECTED MOTION TO EXCLUDE TESTIMONY OF VICTOR WIENER The City of Detroit, Michigan (the “City”) submits its corrected motion to exclude the testimony of Victor Wiener, a putative expert offered by Financial Guaranty Insurance Company (“FGIC”).1 In support of its Motion, the City states as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. Victor Wiener is an appraiser who purported to appraise the entire 60,000-plus collection of art at the Detroit Institute of Arts (“DIA”) in less than 1 The City’s corrected motion is identical to the City’s Motion To Exclude Victor Wiener filed on August 22, 2014 (Doc. 7000), except that the corrected motion removes the paragraphs originally numbered 56, 57, and 58, which referred to an order entered by a federal court in In Re Asset Resolution, LLC, No. 09- 32824 (Bankr. D. Nev. May 25, 2010). The City has been made aware that the referenced order was vacated more than two years after it was entered. The corrected motion removes any reference to the vacated order, but this change does not affect the substance of the Motion or any of the grounds for relief that the City identifies. 1 13-53846-swr Doc 7453 Filed 09/12/14 Entered 09/12/14 16:23:50 Page 1 of 361 two weeks—a feat that even Mr. Wiener admits had never been achieved in the history of art appraisal. -

Ann C. Gunter

Ann C. Gunter Bertha and Max Dressler Professor in the Humanities Professor of Art History, Classics, and in the Humanities Northwestern University Mailing address: Department of Art History 1800 Sherman Ave., Suite 4400 Evanston, IL 60201 Voice mail 847 467-0873 e-mail: [email protected] Education 1980 Columbia University Ph.D. 1976 Columbia University M.Phil. 1975 Columbia University M.A. 1973 Bryn Mawr College A.B. magna cum laude with departmental honors Professional Employment Bertha and Max Dressler Professor in the Humanities, Northwestern University, 2013– Professor of Art History, Classics, and in the Humanities, Northwestern University, 2008– Head of Scholarly Publications and Programs, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2004–08 Assistant Curator of Ancient Near Eastern Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution (1987–92); Associate Curator (1992–2004); Curator (2004–08) Visiting Assistant Professor, Art History Department, Emory University, Atlanta (1986–87) Visiting Assistant Professor, Departments of Art History and Classics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (1981–85) Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley (Winter– Spring 1981) Director, American Research Institute in Turkey at Ankara (1978–79) Fellowships, Grants, and Awards Visiting Professor (Directrice d’études), École Pratique des Hautes Études, University of Paris (lecture series to be presented in May 2016) Fritz Thyssen Stiftung 2000–01 -

Annual Report 2000

2000 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART 2000 ylMMwa/ Copyright © 2001 Board of Trustees, Cover: Rotunda of the West Building. Photograph Details illustrated at section openings: by Robert Shelley National Gallery of Art, Washington. p. 5: Attributed to Jacques Androet Ducerceau I, All rights reserved. The 'Palais Tutelle' near Bordeaux, unknown date, pen Title Page: Charles Sheeler, Classic Landscape, 1931, and brown ink with brown wash, Ailsa Mellon oil on canvas, 63.5 x 81.9 cm, Collection of Mr. and Bruce Fund, 1971.46.1 This publication was produced by the Mrs. Barney A. Ebsworth, 2000.39.2 p. 7: Thomas Cole, Temple of Juno, Argrigentum, 1842, Editors Office, National Gallery of Art Photographic credits: Works in the collection of the graphite and white chalk on gray paper, John Davis Editor-in-Chief, Judy Metro National Gallery of Art have been photographed by Hatch Collection, Avalon Fund, 1981.4.3 Production Manager, Chris Vogel the department of photography and digital imaging. p. 9: Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of Saint Peter's Managing Editor, Tarn Curry Bryfogle Other photographs are by Robert Shelley (pages 12, Rome, c. 1754, oil on canvas, Ailsa Mellon Bruce 18, 22-23, 26, 70, 86, and 96). Fund, 1968.13.2 Editorial Assistant, Mariah Shay p. 13: Thomas Malton, Milsom Street in Bath, 1784, pen and gray and black ink with gray wash and Designed by Susan Lehmann, watercolor over graphite, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Washington, DC 1992.96.1 Printed by Schneidereith and Sons, p. 17: Christoffel Jegher after Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Baltimore, Maryland The Garden of Love, c. -

American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works 43Rd

Egyptian Glass at the Freer Gallery of Art American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works 43rd Annual Meeting, May 13-16, 2015 Ellen Nigro, Ellen Chase, Blythe McCarthy Department of Conservation and Scientific Research, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution In 1909, Charles Lang Freer bought a collection of 1,388 ancient glass beads, vessels, and mosaic fragments in Cairo, Egypt from the antiquities dealer Giovanni Dattari. The objects are primarily XVIII Dynasty, Ptolemaic and Roman period Egyptian pieces, as well as many later Venetian and Islamic fragments. Although the collection varies in geographic origin and time period, all the pieces are colorful examples of fine craftsmanship, from intricate millifiori inlays to cast amulets and larger vessels. Until 2013, the collection was largely left unstudied and was inappropriately stored. As a result, the Department of Conservation and Scientific Research at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery is rehousing and researching the collection. This poster will focus on the storage project and the challenges associated with rehousing a large collection of small objects while touching on the historical and technical research. Technical Analysis The purpose of the technical study is to characterize the materials and techniques of the collection and to sort Research in the Freer Gallery Archives some of the objects by time and place according to the technical data. This study included the following techniques: Mr. Freer travelled to Egypt several times between • x-radiography of the vessels to assess the manufacture techniques 1907 and 1909, where he purchased this collection • qualitative x-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy to analyze lead content and colorants on a large number of of glass, as well as a number of faience pieces, objects within the collection manuscripts, and funerary objects.